Narrhalla (newspaper)

The Narrhalla , also Narrhalla - Mainzer Carneval Zeitung is a newspaper published in Mainz since 1841 , which appears for the respective campaign of the Mainz Carnival . In the first few years, the Narrhalla was an important organ of the political-literary carnival that was just developing and was politically influenced, especially in the late pre-March period . It was therefore often censored in the first few decades , and in between it was repeatedly banned for periods of varying length or even voluntarily discontinued.

Since the post-war period , the Narrhalla has established itself as the most important and continuous print medium for the respective carnival campaign. Their content usually consists of reprinted Carnival lectures, dates for the campaign and additional information on the Mainz Carnival.

The first years: 1841 to 1848

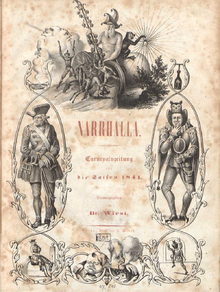

The Narrhalla, a play on words between fool and Walhalla , was first published by Franz Wiest in 1841 and printed under the full title “Narrhalla - Carnevalszeitung for the 1841 season” by Johann Wirth in Mainz. The title page was adorned with allegorical figures for Carnival, such as Till Eulenspiegel . The responsible authorities of the Grand Duchy of Hesse already censored the first edition . For example, the content of the “Terrible but true story of the December revolution in the kingdom of fools”, a parable on the various European revolutions of the time, was cut down. The "freedom of the press" and the opposed censorship of the authorities were therefore also repeatedly topics that the Narrhalla took up.

From 1843 the Narrhalla was edited by Ludwig Kalisch . She appeared eight times, each Sunday, during the campaign. In terms of design, the Narrhalla was characterized by opulently designed illustrations at that time. In terms of content, the critical orientation of the sheet increased under Kalisch. Again and again white spaces pointed to the censorship of content, which Kalisch commented with "The foolish censorship has deleted this verse ..." . In the Carnival campaign in 1844 a critical article appeared about Ludwig I of Bavaria , the father-in-law of the later Hessian Grand Duke Ludwig III. The ruling Grand Duke of Hesse , Ludwig II , to whose Grand Duchy Mainz had belonged since 1816, then had all outstanding editions of Narrhalla for the 1844 campaign completely banned in February 1844.

Ludwig Kalisch, known today as one of the best-known and most prominent representatives of early political-literary carnival journalism, continued to lead Narrhalla as editor in the following campaigns until 1848. He repeatedly castigated repressive politics and life in Biedermeier Germany in the mid-19th century. Century and was in domestic competition with other similar journalistic products such as the "Neue Mainzer Narrenzeitung" by Eduard Reis. When the February Revolution broke out in France in February 1848 , Kalisch was able to celebrate the abolition of press censorship and an incipient change in the political landscape in Germany in the last Narrhalla edition of the Carnival campaign in 1848 .

The Narrhalla until the First World War

After the failed German Revolution, Narrhalla, like most other political-satirical publications, was discontinued for a longer period of time. It was not until 1857 that the newspaper was reissued, this time as “Narrhalla - Official and Government Gazette of Prince Carneval”. The editors were now Peter Sonn, co-founder of the Mainz Kleppergarde, and Ferdinand Heyl, hand-made speaker and fast night in Mainz. In the beginning one was careful about political and social allusions, but soon the tradition of the political and literary narrhalla under Kalisch's tenure as editor was tied back to. After seven years, the Narrhalla was discontinued in 1863. Just like the Narrhalla, other foolish carnival newspapers came and went in the still somewhat restless and inconsistent early days of the Mainz Carnival, all of which only appeared as part of the respective Carnival campaign. In 1902, for example, a “Mainzer Carneval Zeitung under the protectorate of the Mainz Carneval Association” appeared. The editor was print shop owner August Permander. In terms of design, the richly illustrated editions showed clear references to contemporary Art Nouveau . In terms of content, political content and background were dispensed with and limited to reproducing session lectures and hand-made speeches from the respective campaigns.

In 1903 the Narrhalla was brought back to life, this time by the then well-known Fastnights August Fürst and Karl Kneib. It now appeared in a steady rhythm and with a uniformly designed title page, which shows an owl as a symbol of the Mainz fool's wisdom, which shields the Mainz Cathedral and the Gutenberg monument with its wings . In terms of content, the focus was again on the foolish, subtle commentary on politics and society. In the Wilhelmine era before the First World War , ubiquitous militarism , bureaucracy, and arrogance as well as the man's addiction of the German Empire were popular topics among authors and hand-made speeches. The last year of the Narrhalla appeared for the 1914 campaign, which was then to be discontinued after the beginning of the First World War.

New beginning and conformity in the Third Reich

Once again there was a fresh start for the Narrhalla, this time eleven years after the last edition. It was again Karl Kneib who brought out the first post-war number of Narrhalla in 1925. In a special issue he looked back and looked at the last eleven years critically and particularly criticized the post-war situation, especially among the common people and the war profiteers . From 1925 to 1930, Kneib repeatedly had to deal with the censorship authorities of the French occupying powers. In the course of the occupation of the Rhineland as a result of the Versailles Treaty , Mainz belonged to the French-occupied territories and the French occupying power was very critical of the Mainz Carnival in all its forms. Following the tradition of the earlier editions, Kneib and the other authors of Narrhalla criticized the unpopular presence of the French troops more or less openly by means of hints, verbal comparisons and statements that could be interpreted in a variety of ways. This ended with the withdrawal of the last French troops stationed in the Rhineland on June 30, 1930 from Mainz.

The following phase, which was relatively liberal for the editorial staff of Narrhalla, ended in 1933 when the National Socialists came to power . Like all other cultural activities, the Mainz Carnival was also integrated into the national socialists' measures to bring about conformity. The Mainz Carnival with its gardens and activists, major events such as the Mainz Rose Monday procession , carnival sessions and the foolish publications such as the Narrhalla were now controlled and organized with the rest of the cultural scene through the political organization Kraft durch Freude . As early as 1934, the Narrhalla became the "Official organ of the Mainz Carneval Association, the Carneval Club and all the Garden". In January 1935, Karl Kneib, now 83 years old, finally handed over the editorial team to the Mainz Carneval Association .

The Narrhalla appeared regularly up to and including 1939 with several issues for the respective carnival campaign. Soon after the political control of Narrhalla by National Socialist cultural officials, the medium was used for patriotic and pro-regime contributions. In the later 1930s, anti-Jewish and anti-emigrant hate speech should follow, as well as the denigration of dissatisfied sections of the population in the National Socialist regime (known as so-called "complainers"). Nevertheless, well-known Mainz Fastnights such as Seppel Glückert or Martin Mundo managed to place their verbose criticism, also presented in hand-made speeches, in articles in the Narrhalla. Again a war brought about the renewed suspension of the Narrhalla. With the outbreak of the Second World War , all carnival activities in Mainz came to a standstill.

The Narrhalla in modern times

Again eleven years later, the Narrhalla was revived. The first new edition was published for the 1950 campaign at a price of 50 pfennigs. The editor of the first post-war years was the Mainz journalist and Fastnachtter Bernhard Gnegel, who was also an editor at the Allgemeine Zeitung Mainz . As before, these years were also financed and published by the Mainz Carneval Association. The Narrhalla finally functioned as a media platform for the pure reproduction of the partly political, hand-made speeches and carnival songs of the respective campaign. There were also short informative contributions on the motto of the respective carnival campaign, on the current train plaques, on the Rose Monday procession and in general on the carnival actors. In 1958, Hans Halama, also local editor at the Allgemeine Zeitung Mainz and Fastnachter at the Mainz Carneval Association and the Mainz Prinzengarde, took over the editing. The tried and tested concept of content compilation has also been retained here. However, the appearance of the Narrhalla changed, this time to a more elaborate layout with the color-printed motto posters for the respective campaigns on the cover. In 1965, Hans Halama handed over the editing to his professional colleagues Hans Häfner and Helmut Wirth. The latter led the editing of the Narrhalla alone from 1968 to 1986. In 1984, the Mainz Carneval Association decided to reduce the print format while increasing the number of pages from 20 to 24 pages to 48 pages. In 1986 the former Prince of Mainz, Lutz Ebeberhard, and Klaus Knipper, both also journalists for the local Mainzer Zeitung, expanded the editorial team.

For the first edition of Narrhalla for the Carnival campaign in 2016, the editorial team consisted of the editor-in-chief with Jürgen Schmidt as the responsible board member of the Mainz Carneval Association, Michael Bonewitz, Eric Scherer and Maike Hessedenz. There are also eight other editorial staff from various areas of the print media and the Mainz Carnival.

literature

Helmut Wirth: A mirror of the times: The »Narrhalla«. In: MCV Mainz (Hrsg.): Citizens' festival and criticism of the times: 150 years of the Mainz Carneval Association 1838-1988. Verlag Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-87439-148-5

Web links

- Narrhalla - Website Mainz Carneval Association

- Narrhalla - Campaign 2016 (PDF)

- dilibri Rhineland-Palatinate - editions of the Narrhalla from 1841