Mainz Cathedral

The High Cathedral of St. Martin in Mainz , called Mainz Cathedral , is the cathedral (bishop's church) of the Roman Catholic diocese of Mainz and is under the patronage of St. Martin of Tours . The east choir is dedicated to St. Stephen . The building, one of the imperial domes, is in its current form a three-aisled Romanesque pillar basilica , which has Romanesque , Gothic and Baroque elements in its extensions .

Previous buildings

From what point in time the Mainz church was an episcopal church can no longer be conclusively clarified today, as the existing lists of bishops from ancient times are all doubtful. It is therefore also unclear when the city's first cathedral existed. However, one knows from historical sources such as that of the historian Ammianus Marcellinus that a larger community must have existed in the city in the 4th century for which episcopal leadership can be assumed. Ammianus's report on the sacking of the city in 368 mentions a Christian community that was surprised at the celebration of a festival, probably Easter. This celebration would have taken place in the cathedral.

The first reliably attested bishop was Sidonius († after 580) in the 6th century . His church already bore the patronage of the Frankish state saint Martin von Tours . However, the location and size of this church are unknown. The archaeological findings provide little information, more detailed investigations and excavations have not taken place in the past decades. However, since there is a wealth of sources, the location and size of the cathedral and its annexes are the subject of constant discussion. The most famous discussion is that of a "cathedral group" within the city walls, a group of three with a bishopric, pastoral care and baptismal church. Apart from a wall and screed remains as well as a sarcophagus under the Johanniskirche , which in later years was also known as the "Old Cathedral", nothing is testified of this building complex.

Architecture and historical building development

The Willigis Bardo building

motivation

The then Archbishop Willigis (also Arch Chancellor of the Empire ), whose term of office began in 975, had a new cathedral built in Ottonian forms. It is possible that Willigis was motivated to build the building to obtain the coronation right for the Roman-German king . An exact date of the start of construction is not certain. Since the preservation of the right to coronation was not questioned until around 990, the extremely short time until the construction was completed speaks against this theory. A period of 30 years is now considered possible as the construction period. On the other hand, the consecration of St. Stephen's Church is dated to 997 and the likelihood of two large church construction sites at the same time in the same city suggests that construction will not begin until the end of the 10th century.

Even if the start of construction and the related motives can no longer be proven, it can be said with certainty that pastoral considerations were not the basis for the construction of the cathedral. During the term of office of Willigis, who had previously served at the court of Otto I and who, in addition to his function as Archbishop, was also Imperial Chancellor of the Holy Roman Empire , the city of Mainz prospered because of its new importance as the residence of the most important imperial prince and politician and had several thousand inhabitants. However, there were more than enough parish churches in Mainz for these.

The new cathedral was unnecessary as a parish church, so it was not primarily intended to serve the faithful, but rather to represent the status of archbishop as imperial arch chancellor and royal crown in the Ottonian empire and to make the importance of the Mainz church as the “second Rome” recognizable. Accordingly, the construction was based on the old St. Peter's Church in Rome.

Location of the new cathedral

Willigis had his cathedral built on a wasteland in front of what was then the city center. There was still a settlement there in Roman times , but it was probably abandoned in Frankish times. Remains of walls from Roman times can be traced under the cathedral . For a long time it was suspected that the cathedral stood on the remains of Roman temples. However, the archaeological evidence refutes this view. The new cathedral replaced a previous building, which - as described above - could have been in the immediate vicinity. As stated, it may have been the St. John's Church , which continues to be known as the Old Cathedral (“Aldedum”) ; However, the function of the St. John's Church or its predecessor buildings as a cathedral church has not been finally clarified.

In any case, the monastery church of St. Alban , located in front of the city and dating from late Roman times, had been the most important church in the archbishopric for almost two centuries. Since the church was astonishingly large at about 75 m in length for the time, all important synods and assemblies took place there. The Archbishops of Mainz were mostly buried there at that time.

execution

The reconstruction of Willigis Cathedral today is characterized by the difficulty that, firstly, the building only existed for a very short time in its original state and, secondly, only insufficient archaeological investigations have been carried out. Nevertheless, excavations on Liebfrauenplatz and findings during the major cathedral renovation in 1925–28 were sufficient to describe the basic features of the Willigis building.

Pre-church in the east

In the east there was an antechamber that was connected to the actual cathedral structure. The extent of this porch can be determined quite well by the foundations found during excavations. In the far east there was therefore a rectangular tower about 13.50 m wide, which enclosed an apse that was semicircular on the inside, but rectangular on the outside . Behind it was a 31 m wide and 11 to 12 m long transverse structure. This ensemble probably formed the actual pre-church. It was connected to the cathedral by two low, 41 m long colonnades , which, in terms of the floor plan, look like an extension of the aisles of the cathedral. The similarity to Alt-St. Peter is particularly strong in Rome . The colonnades and the front church were destroyed in the fire disaster of 1009, but the idea of a church in front of the cathedral was retained. The large collegiate church of St. Maria ad Gradus (Church of Our Lady) was later built here .

East building and east choir

The east building consisted of a transept, which was bordered by a stair tower in the north and south. Willigis probably adopted the motif of the stair towers from the Palatine Chapel in Aachen . It can be found at the Michaelskirche in Hildesheim , which began after 1000 and which has many other similarities to the Willigis Cathedral. The building was as wide as the nave and was tripartite, the central nave closed off a transverse rectangular part, the side aisles a square part. The east building was flanked by two towers, which presumably had four closed floors and an open arcade. The four floors of the two towers are among the remains of the Willigis building that still exist today. The towers were later increased several times or reconstructed after being destroyed, for the first time under Willigis' successor Bardo.

The square ends of the side aisles were each listed up to the third floor of the adjacent flank tower. In them, building fabric from the Willigis Cathedral has also been preserved in the form of two rooms. Presumably it was an archive and a sacristy room. They were not accessible from the stair towers, but from the central building, which assumes the existence of corresponding galleries there.

The central building itself was designed higher, reconstructors assume a tower similar to that in Minden or Hildesheim, which was intended to accommodate the bells. Altars set up in the central building established the tradition of the east choir and thus the conception of the Mainz Cathedral as a double choir.

For a long time, the question of whether the Willigis cathedral building already had an east apse was a matter of dispute. The different opinions regarding the appearance resulted from the fact that no foundations of an east apse have survived from that time. The cathedral should therefore have had a flat end in the east, possibly with a central portal and a rectangular central tower. The contrary opinion, based on historical considerations and written records, concludes that an east apse already existed in the original building of the Willigis. The foundations could have been replaced during the later renovations. In the meantime, however, the majority of the thesis about the east apse is rejected.

The meaning or the idea behind the construction of the cathedral with double choir is sometimes controversial. In the past it was often assumed that the two opposite choirs served to symbolize sacerdotium in the west and imperium in the east, i.e. spiritual (embodied by the bishop) and secular (embodied by the king) violence. However, this thesis cannot be proven. In more recent writings it is therefore assumed that the concept of the double choir had liturgical reasons. It made solemn processions possible between the two choirs. Initially, both choirs were used equally alongside each other. Later, the east choir mostly served as a place for the masses of the cathedral parish, the west choir (main choir) as a bishop's choir for the pontifical offices or for the church services of the cathedral monastery. With the relocation of all major church services to the west choir, the east choir lost its importance. Today the liturgy of the hours of the cathedral chapter takes place there.

Nave and crossing

The nave of the Willigis Cathedral was designed as a three-aisled basilica complex. The walls of the central nave were probably supported by columns. Due to the foundations that have been preserved, a clear length of 57.60 m can be precisely concluded. The central nave was 13.60 m wide, the two side aisles 7.70 m each. On the other hand, the original height of the nave is no longer clearly determinable and therefore the subject of historical conjectures.

In the west, the nave opened into an unusually wide transept. The foundations are no longer preserved there, but parts of the northern end of the building, which today form the south wall of the Gotthard Chapel, are. There they are the only remains of the Willigis Cathedral above ground. The width of the transept to be determined in this way shows that the building did not have, as usual, a transept of three squares with the side length of the central nave width (i.e. 13.60 m), but four. The transept was roughly the same width as the long nave, namely 200 Roman feet. The alignments of the central nave walls continued to the west wall of the transept and divided it into a square and two rectangles (so-called "separated crossing") by the columns. However, the foundation plan from the 1920s is not clear at this point, so that there is no one hundred percent certainty about the crossing. The question is not insignificant because it depends on your answer whether the Willigis Cathedral already had a western crossing tower.

Main choir in the west

In contrast to most of the church buildings of that time, whose main choir was always facing east, Willigis had his cathedral built facing west, as was the case with the great basilicas of Rome. Least of all can be said about the west building of the Willigis, as the foundations there were removed when the west building was rebuilt in the 13th century. However, it can be assumed that the transept was followed by a further square choir , to which an apse was added. This is suggested by the construction of the transept and the location of the altar in the baroque building; it would also correspond to other designs in Hildesheim, Gernrode and Hersfeld. The other solution would be a direct connection of the apse to the transept, based on the exact model of St. Peter in Rome. Overall, the actual cathedral building with a choir square measured 105 m, the entire system was 167 m (570 Roman feet).

Destruction and rebuilding

On August 29, 1009, the day of the consecration (other sources speak of August 28), the building was destroyed by fire. The reason for this was probably the festive illumination of the cathedral on the occasion of the consecration day. On such occasions, churches in the Middle Ages were often lit with torches .

Under the two immediate successors of Willigis, Erkanbald and Aribo , the ruined cathedral remained a building site. The construction was not completed again until Archbishop Bardo (1031–1051), so that the cathedral was inaugurated on November 10, 1036 in the presence of Emperor Konrad II . The cathedral was now designed as a pillar basilica and by then at the latest had an apse in the east, which, according to archaeological findings, cannot be thought of as the current round apse attached to the east transept. Rather, this can also have been made rectangular and straight.

The open colonnades leading to the pre-church, as well as the pre-church itself, were not rebuilt. For this, the cloister and the monastery buildings were built around the cathedral. Aribo was the first archbishop to be buried in Mainz Cathedral; he found his grave in the west choir of the not yet completed cathedral. Before the cathedral was built, the archbishops preferred the large monastery church of St. Alban, which was then of great national importance at the gates of the city, as a burial place. Willigis was buried in his second church building, St. Stephen's Church.

Color design of the Bardo building

The color design of the cathedral at that time is still a major research area of the respective cathedral curator today . It was not until the renovation of the eastern building, which today still contains many components of the original structure, that discoveries were made in 2002 that suggest the appearance of the cathedral before the renovations by Emperor Heinrich IV . After that, the outside of the cathedral was plastered in white, with pilaster strips and cornices made of red and yellow sandstone not being plastered. The interior was probably whitewashed in the middle of the 11th century under Archbishop Bardo. The interior of that time, however, mostly no longer corresponds to the current building stock (see below).

One can only speculate about the color design in the late Middle Ages . However, it is possible that evidence will be found during further renovation work as part of the cathedral renovation that began in 2001. Only the color design of the Baroque and 19th century is known more precisely (see there).

Of the entire Willigis Bardo building, only the stair towers in the east and a few remains of the wall, including on the south wall of the Gotthard Chapel, are above ground . The rest of the building was gradually replaced by new buildings in the following centuries.

The east choir of Emperor Heinrich IV.

Funding by Emperor Heinrich IV is of great importance for the building history of Mainz Cathedral . The cause was the fire of 1081, in which the cathedral was again badly damaged. Heinrich IV., Who had already had the Speyer Cathedral rebuilt, began around 1100 with the construction of the destroyed cathedral in the Lombard style .

He had the old end of the east building replaced by an apse with large blind arcades and a dwarf gallery of the Upper Rhine type. Such an element can be found for the first time in the Speyer Cathedral, the east apse of the Mainz Cathedral is the second example. Above it is a gable with five niches rising from the right and left . This motif was probably also adopted from the Speyer Cathedral.

In addition, the builders of Heinrich IV replaced the (presumed) square tower of the Willigis-Bardo building with an octagonal dome. This middle east tower has been considerably redesigned several times over the years. The current version is a creation by PJH Cuypers from 1875 (see below). The emperor had a three-aisled hall crypt begin under the new east choir, the style of which was probably also based on the crypt of the Speyer Cathedral. However, this was probably canceled again during the construction phase in favor of a continuous floor level.

In order to be able to wall up the new large tower at all, the east transept was raised by twice and widened almost twice. To the right and left of the apse, two large step portals were built in, which are among the oldest of their kind. They led into the aisles. Two more floors were located above the entrance area of the portals, flanking the east choir. The purpose of the rooms has not been fully clarified. The lower ones, which date from the time of Willigis (see above), could have been sacristy, archive or other storage rooms. They were still only accessible from the choir room. The upper ones were probably chapel rooms, as can be found comparable in the collegiate church of St. Gertrud in Nivelles , at the Essen cathedral and at the Eichstätter cathedral .

The death of the imperial sponsor in 1106 meant a deep turning point in the construction work. What had started was completed in a hurry, other things were suspended for the time being or were completely discontinued because the executors Magistri Comacini - stonemasons from Lombardy - moved on. The death of the emperor led his biographer to prosaic lamentations, which make it clear what the emperor's death meant for the Mainz Cathedral (“Hay Mogontia, quantum decus perdidisti, quae ad reparandam monasterii tui ruinam talem artificem amisisti! Si superstes esset, dum operi monasterii tui, quod inceperat, extremam manum imponeret, nimirum illud illi famoso Spirensi MONTREIO contenderet “- Woe to Mainz, what ornament, what artist you have lost to restore your ruinous minster! If he had stayed alive until he had the last hand had laid the cathedral construction begun by him, it would undisputedly have rivaled the famous Speyer cathedral). Because Heinrich IV was an emperor who worked on the construction of the cathedral, the Mainz Cathedral, together with the Worms Cathedral and the Speyer Cathedral, is one of the three Rhenish imperial domes .

When the work was continued has been the subject of much research. The reference point here is the abundant building sculpture on the dwarf gallery of the apse and the portals. According to this, it is assumed that the unfinished parts of the transept and the portals were built around 1125 to 1130.

The creation of today's nave

The further construction work on the cathedral was probably continued immediately after the completion of the eastern section. The old nave of the Willigis-Bardo building was replaced step by step, with the exception of the foundations.

In between, the St. Gotthard Palace Chapel was built right next to the cathedral and originally with a direct connection to the Bishop's Palace of Archbishop Adalbert I of Saarbrücken (1110–1137) . A contemporary source praised its splendid “tectum”, which, in addition to “roof”, can also mean “ceiling” and thus “vault”. In accordance with its construction time, the chapel still has classic Roman groined vaults .

However, the lack of imperial funding meant that the nave did not achieve the same quality as the east choir. For this, the emperor had high-quality sandstone from the Spessart and Haardttal brought in, which was also used for the Speyer Cathedral and the Limburg an der Haardt monastery church . Now shell limestone from the nearby Weisenau quarries was used.

In addition, the cathedral building in 1159 suffered a setback; In an uprising against Archbishop Arnold , the citizens of Mainz stormed the cathedral and devastated it. In the following year they even killed the archbishop.

As in the Speyer Cathedral (and numerous other basilicas of that time), the nave has a bound system and side aisles with groin vaults (see below), but these are almost the only common features. The walls of the central nave between the arcades to the side aisles and the upper aisles , even if only indicated in the form of blind arcades , already have a triforic floor and thus a three-zone wall elevation, as has been found in Norman church construction in England and Normandy since the late 11th century . The Ste-Trinité abbey church in Caen , built 1060–1130 , also only has blind arcades as a triforium, but more splendid than in Mainz. The windows of the upper aisle were moved together in pairs, which suggests that a vaulting of the central nave was planned from the outset. - The nave walls of the Mainz Cathedral are at least younger than the vaulting of the Speyer Cathedral initiated by Heinrich IV.

From 1183 there is a chronic note that the cathedral did not yet have any vaults.

The vaulting began around 1190 and was completed in 1200. The central nave vaults were created from scratch and the aisles restored. While the side aisles still received classic Roman groin vaults , the central nave was covered at a height of 28 m with pointed arched ribbed vaults, which reveal the influence of the French early Gothic , of which the ambulatory of the abbey church of Saint-Denis , built in 1140, is considered. The combination of Romanesque design of the walls, windows and portals with Gothic vaults is typical of late German Romanesque .

The nave was therefore more modern, but not as splendid as the Speyer Cathedral, for which more money was available as an imperial representative building. The outer walls of the old Willigis-Bardo building remained in place until the aisles were vaulted around 1200. The walls that were present or created when the vault was closed almost completely disappeared when Gothic side chapels were added to the nave in the north and south from 1279. What remains, however, reveal that the floor level inside the cathedral must have been raised in the meantime: the bases of the walls are higher than those of the opposite pillars of the central nave. The construction work on the nave was made more difficult by a number of fires.

The west building

It was only during this last phase that the decision was apparently made to replace the old west building of the Willigis. The execution took place from 1200 to 1239 largely in the style of the Lower Rhine late Romanesque and is at the same time one of the most outstanding examples of this building era. This can be seen above all in the very finely designed and artistically well developed capitals and a more extensive use of architectural decor, which over time had given way to the strict forms of High Romanesque. During this construction phase, the Gothic era had long since begun in France . As early Gothic elements there are buttresses, some pointed arches and for the Romanesque rather unusually long windows in the west choir on the west building of the Mainz Cathedral.

execution

The builder of the west building played it safe and first removed all remains of the foundations from the previous building. Therefore, the Willigis building can no longer be safely reconstructed at this point. It is also possible that at that time it was already foreseeable that the old foundations could not bear enough load on the difficult ground.

Then the new transept was erected first. So that the vaults could be made more or less square, it was shortened considerably to the north and south compared to the previous building. The old walls were laid down, with the exception of those parts in the north to which the Gotthard Chapel, completed in 1137 (see below), was attached. Instead, thicker walls with large buttresses were erected. The new crossing was crowned with a large octagonal dome, which is richly decorated on the inside by surrounding blind arcades, round arch friezes and column capitals.

A rib-vaulted choir square connects to the crossing, i.e. a further yoke with the side length of the transverse arms, which are larger than the yokes of the central nave. It is based on the Lower Rhine model, albeit further interpreted, as a trikonchos , i.e. with three apsidia on the outer sides. However, these are not round, but are designed on three sides by double refraction and also provided with buttresses. The two western pillars of the square are solidly bricked in order to be able to support the two octagonal flank turrets.

The exterior of the west building

The exterior of the west building offers rich architectural decorations, at least as far as the upper ends of the walls are concerned. Since the cathedral was always rebuilt, there was no interest in excessive architectural decoration in the lower areas. The upper finishes, however, are all the more richly decorated.

The windows of the transepts are framed with columns, which are crowned by high quality capitals. The gables are richly decorated with round arch friezes, the gable of the richly decorated north wall (this turned towards the Archbishop's Palatinate) with blind arcades .

The choir square is crowned on all three open sides with gables, which in turn are adorned with splendid spoke roses, which are among the oldest of their kind in Germany. Where the gables cross over the west choir, a statue of the main patron of the cathedral and the diocese, St. Martin , has been enthroned since 1769 (replaced by a copy in 1928) . The apses themselves are encircled by a colonnaded dwarf gallery of the Lower Rhine type, from which the spiral stairs of the flanking turrets can be entered, which only begin at this height. A spiral staircase, so that the western parts of the cathedral can also be accessed directly from the ground (and not via a detour from the east), was added later to the north connection between the transept and the trikonchos, for which the column gallery had to be redesigned at this point. The construction work was probably related to the establishment of the first guard room (Glöcknerstube) on the west wall of the north transept.

The large west tower has been rebuilt several times over the years. In the Romanesque era it was much lower than it is today. The lower visible floors with their round arches still date from this time. Before 1490, the Gothic storey was added and a corresponding spire was created, which, however, burned down in 1767. Then the decision was made to use today's stone version, which was created by Franz Ignaz Michael Neumann (more on this below).

After completion of the construction work, the cathedral was on July 4th, 1239 by Archbishop Siegfried III. inaugurated by Eppstein . The date is still considered the official cathedral church fair.

Gothic style at Mainz Cathedral

At the time when the late Romanesque western building was being built, the Naumburg master created a now Gothic western latin that showed a representation of the Last Judgment . In 1682 it was canceled as a result of the liturgical reforms of the Council of Trent . The two spiral staircases that were inside the rood screen were integrated into the grandstands built in 1687, which to this day delimit the crossing to the north and south. Otherwise there are only fragments of the artworks by the Westlettner. Some, including the famous head with a bandage and the depiction of the Last Judgment with Deesis and the procession of the blessed and damned , are now kept in the Cathedral and Diocesan Museum. Another, the Bassenheimer Reiter , a Martinus relief, is in the Bassenheimer parish church of St. Martin .

From 1279 onwards, Gothic side chapels with large tracery windows were gradually added to the nave sides of the cathedral . In the case of the chapels on the north side, which extends towards today's market square, the aim was also to create a representative facade in a modern style. Unlike today, the cathedral was not renovated at this point.

Archbishop John II. Of Nassau left off in 1418 before the east choir a two-story, free in the nave standing grave chapel built, nor the underground part (of the today Nassauer (sub) chapel is preserved). The exterior of the cathedral was also designed in a Gothic style until the 15th century: the two-storey cloister was rebuilt from 1390 to 1410 . It is believed that Madern Gerthener was involved in the construction of the Nassau chapel and the cloister. In any case, the portal of the memorial chapel at the transition to the western cloister wing comes from him.

The crossing towers in the east (from 1361) and west (from 1418) were topped up with Gothic bellhouses and were given steep Gothic spiers . This work was not completed until 1482. The steep spire of the east tower was replaced by a flatter eight-sided point as early as 1579. Because of the enormous weight of the eastern bell chamber, a Gothic support pillar had to be added to the east choir after 1430, which was only removed when the bell storey was demolished in 1871. The stair turrets and even the Gotthard Chapel were given Gothic turrets and roof turrets . The collegiate church of St. Mariagreden (Liebfrauen) in front of the cathedral was completely rebuilt. After the end of the Gothic building work, no significant changes were made to the building itself until 1767, only a few renovation measures. Only the equipment (see there) changed.

Baroque art

The large western crossing spire, burned down by lightning strike on May 22, 1767, like the rest of the roof , was given a multi-storey stone spire by Franz Ignaz Michael Neumann , son of Balthasar Neumann , in 1769, to which the Mainz Cathedral owes its characteristic image to this day. Neumann had all the roofs of the west building made of stone to make them fire-proof. He also redesigned the western flank turrets. Neumann worked in baroque forms, but also incorporated the late Gothic and Romanesque style elements that were already present on the cathedral in his work.

Furthermore, the Gothic gables of the side chapels disappeared and their pinnacles were replaced by urns. Today's weathercock of the west tower, the so-called “Domsgickel”, which was and is the subject of numerous literary considerations by Mainz poets and fastnights, comes in its basic inventory from the time of the renovation at that time.

The baroque period also brought changes in the color scheme of the cathedral. Like many new baroque buildings, the cathedral was painted white inside in 1758 and also received colorless windows. It can therefore be assumed that the cathedral was not previously whitewashed like the Willigis Bardo building.

The cathedral and the renovations of the 19th century

The downfall of the old archbishopric and the confusion associated with it did not leave the Mainz Cathedral unscathed. When the city was bombarded by the Prussians in 1793, the cathedral was badly hit. In particular, the eastern group and the cloister were badly affected. The Gothic Church of Our Lady St. Maria ad Gradus was also badly damaged and even demolished in 1803, although this was not absolutely necessary.

In the times after the Mainz Republic , the cathedral was used as an army camp or magazine, and the furnishings were sold. After all, the cathedral itself was threatened with demolition. However, with the help of Napoleon , Bishop Joseph Ludwig Colmar averted this fate . Colmar restored the cathedral to its original purpose. This also included extensive restoration work that dragged on until 1831. First, the interior was made usable again and the roofs repaired. This work was interrupted by the repeated confiscation by the French Grande Armée in 1813, which, after its defeat, used the cathedral as a pigsty and a hospital for 6,000 soldiers, some of whom had typhus . Most of the remaining wooden equipment was burned. Its use as an army camp in 1803 had already resulted in the loss of a number of wooden items of equipment. It was not until November 1814 that the cathedral was used again as a church. This was followed by the redesign of the roofs and the destroyed eastern main tower by the grand ducal Hessian court building director Georg Moller . In 1828 Moller added a pointed-arched wrought-iron dome to the old Gothic bell chamber .

This was demolished again in 1870, together with the Gothic bell chamber, because cracks in the masonry made it suspect that the tower was too heavy - probably also because the iron dome was not accepted by the public.

In 1875, PJH Cuypers built today's neo -Romanesque eastern crossing tower.

Cuypers' work marks the end of this longer construction phase on the eastern building. Since the crossing tower now lacked the heavy bell storey, the old Gothic support pillar inside was demolished. In addition, the east choir crypt was rebuilt, whereby the original height of the crypt of the Heinrich IV building was renounced.

Historical photographs from the late 19th century also show that the cathedral was now painted in bright colors contrary to the baroque color scheme. The paintings are works from the Nazarene school , which were mainly executed by Philipp Veit between 1859 and 1864. Of these, only the New Testament Bible scenes in the arches of the nave are preserved today.

Restoration work in the 20th century

In the 20th century, the cathedral was built primarily with a view to preserving it. The first measure became necessary after the wooden post gratings under the cathedral foundations began to rot due to the lowering of the water table and the cultivation of rain gutters. The sinking was a result of the embankment of the Rhine towards the end of the 19th century. Work began in 1909. When it was temporarily suspended at the end of the First World War, the damage to the wall caused by the unstable foundation increased so that the very existence of the cathedral itself was endangered. The cathedral was therefore placed on concrete foundations from 1924 to 1928. The vaults and tower superstructures were secured with concrete and steel anchors, the upper aisle wall reinforced with a load-bearing shotcrete layer (this “gate locking” was used to close the numerous historical scaffolding holes, which makes dating the central nave difficult today). In addition, today's reddish, marble-looking floor made of tuber lime was drawn in and most of the paintings by Philipp Veit were removed. Instead, the painter Paul Meyer-Speer (1897–1983) developed a system from the different inherent colors of the sandstones, in which he colored the stones inside according to precisely predetermined gradations. This type of color design can still be seen today on the central nave of the Speyer Cathedral .

During the Second World War, Mainz was the target of major air raids several times . The cathedral received several hits in August 1942. The upper floor of the cloister was destroyed and most of the roofs of the cathedral burned down. The vault, however, survived all the bombardments. Further damage was caused by bombing on September 8, 1944 and February 27, 1945. The external restoration work after the war, which also removed damage caused by weathering, dragged on into the 1970s, as did the work on the interior design, in particular the new glazing. Finally, the outside of the cathedral was colored red with mineral paints; Diocesan conservator Wilhelm Jung was decisive here . With the red coloring, the color scheme was similar to that of most of the historic Mainz buildings (for example the Electoral Palace ). During the renovation of the cathedral in 1958–1960, Meyer-Speer's interior color concept was partially withdrawn by taking out the strongest colors, so that the colors of the individual stones now differ only slightly from one another. In addition, the vault caps were painted white at that time.

After the renovation was completed , the millennium was celebrated in 1975, following the tradition that construction began immediately when Willigis took office (975). In 2009 another millennium was celebrated to commemorate the first completion, also during the term of office of Willigis (1009).

Restoration work in the 21st century

In 2001 the cathedral began to be renovated again, the duration of which was estimated at ten to 15 years at the beginning of the construction work. All parts of the cathedral are covered, both inside and outside. While the exterior color scheme is not available due to the uniformity in the cityscape, a return to the color scheme after the renovation in 1928 is being considered inside (see above).

The work on the east group has now been completed, as has the new version of the upper aisles of the nave. The western group has been renovated since spring 2010, especially the crossing tower there, the entire top of which was replaced in the course of the work. The cathedral gickel was removed at the end of February 2013 and was gilded as part of a public exhibition until May 30, 2013 in the cathedral and diocesan museum. On July 19, the new Domspitze with Domsgickel was put on.

Inside, the sacrament chapel was reopened on September 11, 2007 by Cardinal Karl Lehmann after extensive renovation . During the renovation, the two windows of the sacrament chapel received new glazing, which was designed by Johannes Schreiter . The altar was restored and an altarpiece of the " New Wild " Bernd Zimmer was attached. The Gotthard Chapel was renovated between 2009 and 2010.

In July 2013 the spire of the westwork will be renovated. The 240-year-old spire was copied true to the original by employees of the Mainzer Dombauhütte and made available in two sections for a complete replacement, which took place on July 17th and 18th. According to the diocese of Mainz, the costs for the exchange amounted to approx. 500,000 euros. Contrary to the original schedule, the renovation of the west choir and the small flanking towers could not be completed at the end of 2016 and will take several years to complete.

Royal coronations in the cathedral

During the Middle Ages, several (counter) royal coronations took place in Mainz. In the High and Late Middle Ages, Aachen was the place of coronation legitimized by tradition, a coronation in Mainz was viewed by political opponents as a formal error that made the coronation invalid. Not all coronations were carried out in the Mainz Cathedral itself, as, as described, it was damaged several times by fires during the Middle Ages.

The coronations of

- Agnes of Poitou in 1043 by Archbishop Bardo ;

- Rudolf von Rheinfelden (also: Rudolf von Schwaben) as counter-king to Heinrich IV on March 26th or April 7th 1077 by Siegfried I of Mainz ;

- Mathilde (later wife of Heinrich V ) by the Archbishop of Cologne Friedrich I von Schwarzenburg on July 25, 1110;

- Philip of Swabia (September 8, 1198) by Bishop Aimo of Tarentaise ;

- Friedrich II on December 9, 1212 by Siegfried II von Eppstein ;

- Heinrich Raspe as counter-king on May 22, 1246 by Siegfried III. from Eppstein .

The coronations of

- Heinrich II. (June 6th 1002) by Archbishop Willigis and

- Conrad II (September 8, 1024) by Archbishop Aribo

probably took place in the old cathedral, the neighboring St. John's Church .

Furnishing

One of the richest church furnishings in Christendom can be found in the Mainz Cathedral - although it has lost large parts of its furnishings over time . The most important pieces are the altars and the funerary monuments of the archbishops and some prelates .

Equipment at the time of Willigis

The earliest piece of equipment, the creation and loss of which is known, is the so-called Benna Cross . This triumphal cross was made of wood covered with gold plates with a larger than life figure of Christ made of pure gold . Archbishop Willigis had financed it with tribute income from the Lombards . During the High Middle Ages , the archbishops melted down the cross piece by piece between 1141 and 1160 to finance their official business.

On the other hand, the large bronze doors that Master Berenger made on behalf of Willigis have been preserved. According to the inscription, these doors were the first metal-made doors since Charlemagne , which is viewed by proponents of the theory that Willigis wanted to replace Aachen as the coronation site with his cathedral building, as a further demonstration of his claim. The doors were originally installed in the Church of Our Lady in front of the cathedral. This stretched towards the Rhine and received the king or emperor arriving by ship after the ceremony. In 1135, Archbishop Adalbert I of Saarbrücken had the city privilege he had granted engraved in the upper part of the doors . After the Liebfrauenkirche was demolished in 1803, the doors came to the cathedral and today form the market portal there .

Not much is known about the rest of the furnishings in Willigis Cathedral. Since the building burned down on the day of dedication (or the day before), it may never have been richer in furnishings.

Due to the frequent construction work and redesign of the cathedral, apart from the building fabric and some grave finds, there are no more Romanesque elements on the cathedral today. An exception is the so-called Udenheimer crucifix , which is not part of the original furnishings, but was only purchased from the church in Udenheim in 1962 . The exact time of origin of this cross is controversial, it is partly dated back to the 9th century, mostly a time between 1070 and 1140 is assumed.

Gothic furnishings

Only with the onset of the Gothic did the wealth of furnishings steadily increase. Gothic altars were built into the side chapels, which were added from 1278, and were gradually replaced with the onset of the baroque era. The most important surviving altar is the Marienaltar with the late Gothic "Beautiful Mainzerin" flanked by Saints Martin and Boniface (around 1510). The altar shrine itself, however, dates from 1875. The large pulpit in the central nave also dates from the late Gothic period , but was so thoroughly renewed in 1834 that only small parts of the original work remain. The Church of Our Lady originally housed other Gothic furnishings in the cathedral today. This includes, in particular, the large baptismal font in the north transept, which dates from 1328 and is one of the largest - if not the largest - objects ever cast from pewter . The baptismal font was in the Liebfrauenkirche because it served as the baptismal church of the cathedral parish. At that time there was no baptism in the cathedral itself.

The burial scene of the so-called Adalbert Master , which is located in a side chapel of the cathedral, can be dated to the transition phase from the late Gothic to the Renaissance . On the other hand, the Westlettner by the Naumburg master is only preserved in fragments . Most of the remains can be found today in the Cathedral and Diocesan Museum.

Equipment from the Baroque and Rococo periods

In 1631 Mainz was occupied by the Swedes , who had the cathedral partially looted. Therefore, parts of the former Mainz cathedral treasure can still be found in museums in Uppsala today . Three cathedral altars in Mainz, each with two wings by the painter Matthias Grünewald , were stolen by the Swedish soldiers. “They were taken together in 1631 or 32 in the wild war at that time, and sent to Sweden in a ship, but along with many other similar tricks they perished due to shipwreck in the sea,” wrote the biographer Joachim von Sandrart in 1675. Since the The city of Mainz experienced a new heyday after the Thirty Years' War during the Baroque period , especially under the Archbishops Johann Philipp von Schönborn (1647–1673) and Lothar Franz von Schönborn (1695–1729), which was accompanied by brisk building activity, is also absent in the Cathedral not on baroque furnishings. Many of the Gothic altars were replaced by Baroque ones, and other altars were added, such as the Nassau Altar from 1601, which is located in the north transept. A year later, the upper floor of the Nassau Chapel, which protruded into the middle of the central nave of the cathedral, was demolished. The basement has been preserved to this day. In 1687 baroque stands (chorettes) were built between the northern and southern crossing pillars, on which the musicians stood during masses, and later an organ was also installed there.

The largest and most important work of art of that time, however, is the large choir stalls in the west choir , which are already rococo . It was created by Franz Anton Hermann between 1760 and 1765 . The ornamentation of the choir stalls, which is crowned by a statue of St. Martin above the bishop's canopy, does not represent a biblical cycle, but rather depicts the coat of arms of the archbishopric and its dignities and should therefore give an impression of the power and glory of the old Mainz church produce. The choir stalls in the east choir are much simpler and come from the St. Gangolf Castle Church, which was demolished in Napoleonic times .

Later equipment

In the 19th century, the main focus was on building. With the exception of the funerary monuments for the bishops of this century and the shrine for the group of figures of the Marian altar, little was added to the furnishings. The large bronze cross from the 20th century, reminiscent of historical models, should be mentioned in the west crossing, which was created for the 1000th anniversary of the cathedral. The “Shrine of the Mainz Saints” in the east crypt of the cathedral, which was donated in 1960, is also important.

The funerary monuments

The grave monuments are important for the history of art . The Mainz Cathedral houses the most extensive collection of such works of art in the area of the former Holy Roman Empire. The grave monuments are the expression of the self-image of the Archbishops of Mainz, who at that time not only presided over the largest ecclesiastical province on the other side of the Alps, but were also the highest-ranking imperial princes and for a long time representatives of the Pope and Primate Germaniae . With the erection of a grave monument for the respective predecessor, the incumbent placed himself in the ranks of the Archbishops of Mainz and thus claimed the privileges they had been entitled to for generations. But not only archbishops but also members of the Mainz cathedral chapter had grave monuments erected in the cathedral. Stylistically, all epochs of European art history are represented in the grave monuments, from the Gothic to the Baroque to the monuments of the 19th century, which are again oriented towards the Middle Ages. Figurative representations began to be dispensed with towards the end of the 19th century.

The oldest of these monuments is that of Archbishop Siegfried III. von Eppstein († 1249). It shows him - as can also be seen later on the Peters von Aspelt monument - as a royal crown and was originally intended as a grave slab, which can be seen on the chiseled pillow under the archbishop's head. Only later was it attached vertically to a pillar in the nave, and in 1834 it was painted with oil paint.

The first grave monument attached directly to the wall was that of Archbishop Konrad II von Weinsberg († 1396). The monuments of his successors in the 15th century are among the highest quality. Particularly noteworthy are the grave monuments of Archbishops Johann II of Nassau and Konrad III. from Dhaun .

At the transition from the late Gothic to the Renaissance , the grave monuments of Archbishop Berthold von Henneberg are noteworthy, who was probably the first to have two monuments made during his lifetime. The grave slab consists of red marble, which was extremely expensive at the time, and was made with a quality that stands out from other grave monuments. The monument to Archbishop Uriel von Gemmingen is also noteworthy . It is designed completely differently from all other grave monuments, as it does not depict the archbishop in an imperious pose, but humbly kneeling under a cross.

The grave monument of Archbishop and Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg is definitely part of the Renaissance . Albrecht was Archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg at the same time, which is why he has two pallia on his grave monument . Albrecht also had a grave slab made next to the memorial, which today hangs in the immediate vicinity of the memorial. As the only one of its kind in Mainz Cathedral, its inscription is written in German. The language of forms and colors of the Albrecht monument can also be found - as it comes from the same artist - on the monument to his successor Sebastian von Heusenstamm .

The tomb of the von Gabelentz family was created by Johann Robin, the brother of the Flemish architect Georg Robin , and his workshop around 1590.

The last of these monuments to show the deceased as a statue is that of Archbishop Damian Hartard von der Leyen . After that, only scenes are shown on the monuments - if they still consist of a figurative representation. For example, the only monument dedicated to a layperson shows Count Karl Adam von Lamberg, who fell in 1689, as he climbs out of the coffin to be resurrected . From this era, which can be assigned to the baroque or rococo , the cathedral's largest grave monument at 8.33 m, which represents the provost Heinrich Ferdinand von der Leyen , also comes from .

Around 1800 people began to think back to medieval models. The grave monuments were again designed as tumblers with reliefs , like that of the important Bishop of Mainz Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler . From 1925 all bishops were buried in burial niches in the newly created western crypt.

Attachments and crypts

East crypt

An east crypt was already planned for the time of Emperor Henry IV . Heinrich laid the foundation for a three-aisled hall crypt, which was probably never completed. After the emperor's death in 1106, work on the eastern building was suspended until around 1125. In the more recent plans, however, no crypt was provided, which is why the existing parts were filled with rubble. The crypt was rebuilt from 1872 to 1876. It was possible to largely reconstruct the old system based on the archaeological findings. Both the base plates of the free-standing columns and the steps of the former staircase were found. The wall structure was also preserved and provided information about the shape planned under Henry IV. Due to the similarity to the crypt of the Speyer Cathedral, the other building measures, especially the design of the capitals , were based on the Speyer model. The east crypt is therefore today a three-aisled hall with a length of five bays. It can be reached from the two side aisles via stairs. Inside there is a shrine created in 1960 that keeps relics of the Mainz saints. On All Saints' Day the crypt is therefore the target of a procession at the end of Vespers .

West crypt

The Lullus crypt, named after the first Archbishop of Mainz, was only built in 1927/28 during the major cathedral renovation under the western crossing. It is a rectangular room with a flat ceiling supported by four pillars. A stone altar is built in the west. The crypt has served as the burial place of the Mainz bishops and auxiliary bishops since that time. There are therefore Ludwig Maria Hugo († 1935), Albert Stohr († 1961), Auxiliary Bishop Josef Maria Reuss († 1985), Cardinal Hermann Volk († 1988), Auxiliary Bishop Wolfgang Rolly († 2008), Auxiliary Bishop Werner Guballa († 2012) and Cardinal Karl Lehmann († 2018). The Archbishop of Mainz, Johann Friedrich Karl von Ostein, is also buried there. The crypt is accessible by stairs in the north and south transepts.

Nassauer lower chapel

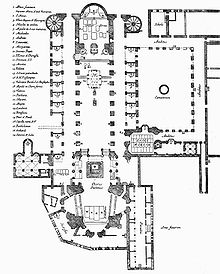

The Nassau lower chapel is located under the central nave of the cathedral to the east (second central nave yoke from the east, see also the floor plan of Gudenus ). It forms a rectangle with sides 7.50 m × 6.60 m. Ten small columns form an octagon and support a small Gothic vault. In the past, as can also be seen on the floor plan of Gudenus, there were two narrow stairs in the nave that led down to the underground chapel. Today the chapel can only be reached through a small corridor opposite the underground entrance to the east crypt. The former staircases now lead into tunnels that are located under the cathedral.

Above the lower chapel was a canopy with a Martin's altar donated by Archbishop Johann II of Nassau in 1417 or 1418. There is evidence of an altar at this point as early as 1051. Archbishop Bardo was buried there in front of an altar, above which was the main cross of the cathedral, from which the name "cross altar" was derived. Similar altars were often found at that time, including in Fulda , St. Aposteln in Cologne and in the St. Gallen monastery . At the time of Archbishop Bardo, the cross altar may have been the location of the so-called Benna Cross, which Archbishop Willigis had donated. The altar of John II was demolished in 1683. The lower chapel is still used today in the Holy Week liturgy , as there is a grave scene ( holy grave ) there. Otherwise it is closed.

sacristy

Today's sacristy was built in three phases. The first part, today's parish sacristy, was probably built shortly after the west choir was built in 1239. Its style is more closely related to Gothic forms than the west building. The first expansion took place in 1501 under Archbishop Berthold von Henneberg (1484–1504), who housed part of the cathedral treasure there. The second expansion took place in 1540 by Albrecht von Brandenburg (1514–1545), who needed the premises to accommodate the so-called Hallesche Heiltum , which he had brought to Mainz.

Gotthard Chapel

The Gotthard Chapel was built by Archbishop Adalbert I of Saarbrücken next to the north transept as a palace chapel until 1137 . In the 12th century, the archbishop's residence was located directly at the cathedral. It stood west of the Gotthard Chapel and was connected to it by an entrance, the wall opening of which is still visible today.

The square Gotthard Chapel is designed as a double chapel . Four pillars divide the space into nine square bays. The middle one remained without a vault, so the archbishop (if he was not celebrating himself) and his court could follow the mass in the upper chapel, the lower chapel was intended for the servants and the people. The Gotthard Chapel is one of the oldest preserved buildings of this type. With the exception of the capitals of the dwarf gallery, which extends around the visible sides of the building, the chapel is poor in architectural decoration. It has lost its central tower, which has been adapted to the respective tastes over time. After the archbishop's palace was relocated from the cathedral to the banks of the Rhine to Martinsburg in the 15th century , the chapel lost its importance. The middle yoke was later vaulted, as the original function of the opening was no longer given.

The chapel has a further extended apse in the middle to the east and two smaller ones to the right and left of it. In the past there was an altar in each of them, the middle one served as the sacramental altar of the cathedral until the 20th century. Today the ceiling opening in the middle of the chapel has been restored. A two-manual organ from the Windesheim organ building workshop in Oberlinger was installed on the upper floor . The middle apse was redesigned in the second half of the 20th century. In 1962 the so-called Udenheimer crucifix, which dates from the high Middle Ages , was attached to the front . The chapel is used for the daily masses of the cathedral monastery.

Cloister

A cloister was never built at Willigis Cathedral. The first cloister of the cathedral was built by the successors, but this cloister - probably renewed several times - is no longer preserved. The present cloister was built between 1400 and 1410 in the Gothic style on the south side of the cathedral. It is probably the size of its predecessor, from which wall remains and a cellar room from the early 13th century have been preserved. The building, executed in the Gothic style, has three wings and two storeys. This means that it has special features in two ways. Apparently the cloister had only three instead of four wings, because a fourth wing would have covered the large tracery windows of the Gothic side chapels, which were added to the nave of the cathedral in the 14th century. The cloister was built on two levels because the large cathedral library was to be kept on the upper floor.

The cloister consists of 24 bays , which are spanned by a simple ribbed vault. Like all cloisters, it served as a connecting passage between the monastery buildings erected around it and above all as a burial place for members of the cathedral monastery. In 1793 he was badly hit when the town was bombarded and heavily restored in the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1942 the cloister burned down after being hit by bombs. It was then gradually restored from 1952 to 1969. Today the cathedral and diocesan museum is located on the upper floor . The basement is still used today as a processional path, and there are also a number of grave monuments and excavation finds. The grave monument of the canon and cathedral builder Johann von Hattstein († 1518) is adorned with a Pietà and is considered the first Renaissance monument in the Middle Rhine region. The area enclosed by the cloister is now used as a cathedral cemetery.

Memory

The so-called Memorie is attached to the south transept in the west. It was built in the late Romanesque construction phase from 1210 to 1230. The Memorie is the former chapter house of the cathedral chapter. Since the capitulars had the right to be buried there, the chapter house, as in other cathedral buildings (Bamberg, Eichstätt, Würzburg) gradually became a mausoleum . The sessions of the chapter therefore took place later in rooms on the south wing of the cloister, which, in contrast to the Memorie, were partly heatable. The old hall then mainly served to commemorate the dead, from which the current name is derived. The stone throne on the west side of the annex and the surrounding stone bench on the walls still testify to the function as a chapter house.

The memorie is a square room with a side length of 12.20 m, which is spanned by a single vault (ribbed vault) and in this respect deviates from the shape customary at the time, according to which the chapter rooms were divided into nine vaulted yokes. However, the builder indicated such a subdivision by dividing the west and south walls into three arches. It is also noticeable that the cloister does not run past the chapter house as it usually does, but is interrupted by it. In the west, the cloister can therefore only be entered through the memorie.

In the east, the Memorie had a small apse from the beginning, in which an altar was also set up. The Romanesque arch over the wall opening is still preserved today. The apse, however, was torn down and replaced by a Gothic building in 1486. The original access to the south aisle, a Romanesque portal over which St. Martin is enthroned, was later walled up and replaced by a Gothic portal.

Nikolauskapelle

The Nikolauskapelle is directly adjacent to the cloister and memorie. A chapel with this patronage is attested as early as 1085, the current building was built before 1382, i.e. before the current cloister was built.

The chapel forms a rectangle consisting of three bays, with the apse with the altar, which no longer exists, was attached to one long side because of the east. The patronage suggests a connection between the chapel and the cathedral school, as Nikolaus von Myra is seen as the patron saint of children. Nonetheless, today's chapel mainly served as an extension of the memory.

There is a double spiral staircase between the Memorie and the Nikolauskapelle. Such systems are rarely found. The two spirals run one above the other, so that the facility can be used from Memorie or St. Nicholas Chapel to climb or descend from the upper floor of the cloister without meeting each other.

Today the cathedral treasure is on display in the Nikolauskapelle.

Monastery building

The architectural history of the monastery buildings on the cloister has not been adequately researched. Originally, these buildings served the common coexistence (vita communis) of the members of the monastery similar to the monasteries. The coexistence of the cathedral monastery ceased in the middle of the 13th century, the members now lived in their own houses. The former dining and dormitories, the warming rooms and other rooms were then given different provisions, possibly also the cathedral school.

A former 51 m long building, which is divided in two, still exists on the south wing. In its present form it comes from the 14th century. After the memorie was no longer used as a chapter house, the chapter sessions took place in rooms in the south wing. There were heated rooms there. In 1489 a small chapter room was added, which still exists today. Most of the former monastery buildings are now occupied by the Cathedral and Diocesan Museum .

Organs

The Mainz Cathedral has one of the most complicated organ systems in Europe. To a large extent, it goes back to an organ that was built in 1928 by the Klais organ building company (Bonn) and modified and expanded by the Kemper organ building company in the course of the cathedral renovation in the 1960s . For reasons of monument protection, the individual works were inserted as inconspicuously as possible into the church and distributed over seven locations. The entire system has 114 registers with 7984 pipes, which can be played from a general console on the south choir.

history

The first evidence of an organ in Mainz Cathedral dates back to 1334. However, they only provide information about the use of an organ in church services, but not about the instrument as such.

In 1468 there was evidence of an organ on the Ostlettner, which was used to accompany the choir. This instrument could come from Hans Tugi (also: Hans von Basel). This Hans Tugi probably also built the first verifiable nave organ in Mainz Cathedral; According to some sources, the instrument was built in 1514; According to other sources, Hans Tugi only made changes to the instrument in 1514, which he is said to have built in 1501.

The cathedral organs were thoroughly restored for the first time in 1545/46. The sources show that the instruments had to be serviced or restored at relatively short intervals, which was probably related to the climatic conditions inside the basilica. In 1547 another organ was built on the Westlettner, which had to be restored together with the nave organ in 1560. The work was carried out by Veit ten Bent , who subsequently built a completely new organ for the nave in 1563. This instrument consisted of the main work, Rückpositiv and pedal and was hung as a so-called " swallow's nest organ " in the central nave opposite the pulpit.

In 1702 the dean of the Johannesstift, Johann Ludwig Güntzer, donated a new organ for the now baroque Westlettner; this instrument was named after him as the "Güntzersche Chorettenorgel". In 1792 this organ was dismantled and parts of it were relocated to other organ buildings in Hochheim and Miltenberg . In 1793 the Prussians bombarded Mainz , which was occupied by the French, and also destroyed the nave organ of the organ builder Veit ten Bents from 1763. Jeanbon St. André , who was Prefect in Mainz under Napoleon , even seriously considered the damage to the cathedral to tear down.

After the cathedral was rebuilt in 1803, at least the remains of Güntzer's organ were used to erect a new organ - this time on the northern chorette of the Westlettner. In 1866 a new choir organ with 10 stops on a manual and pedal was installed in the west choir . In 1899, the organ builder Balthasar Schlimbach (Würzburg) added another manual to this instrument and moved it to the south side of the west choir behind the choir stalls; the console was placed between the rows of seats, where the console of the west choir organ is still located today. During the renovation work in the cathedral in the 1920s, this organ was so badly damaged that it was decided to build a new one. The new instrument was built by the organ building company Klais (Bonn) and inaugurated in 1928. The new organ was placed completely behind the choir stalls for reasons of monument protection. It had 75 stops on four manuals and a pedal, and had a cone chests and registers with an electro-pneumatic action .

Today's organ system

In view of the location-related unfavorable acoustics, the decision was made in 1960 to rebuild and expand the Klais organ as part of the cathedral restoration. The organ building company Kemper (Lübeck) was commissioned with the changes .

The instrument was divided: two manual works including a large part of the pedal work remained as west choir organ on the left and right behind the west choir stalls. The two other manual works were laid out as a two-part transept organ with the other pedal registers, supplemented by a few registers ; on the south chorette with a free pipe prospect the so-called south pore organ , and on the north wall of the transept in a new case the so-called north wall organ . In 1960 the east choir organ was completely rebuilt by the Kemper company . Kemper also created the large central console on the south choir, which has six manuals and from which every single register of the entire organ system can be played.

Conceptually, the orientation was on the one hand on the then location of the cathedral choir on the north choir and on the increased requirements with regard to the leadership of the congregational singing, which was the reason for the creation of the east choir organ. The latter was due to liturgical changes: the predominant form of mass in a cathedral church, the Latin high mass, did not provide for congregational chanting (in the sense of singing hymns) until the 1960s, it consisted only of Gregorian chant and vocal polyphony.

In 2003, on the occasion of Karl Lehmann's 20-year bishop's jubilee, a register with so-called Spanish trumpets was installed in the bell-ringing room of Mainz Cathedral, which is located high up in the north transept . The whistles called cardinal trumpets greet the bishop on major holidays.

West choir organ

The west choir organ has 35 registers on two manuals and a pedal. It consists essentially (with the exception of Clairon, No. 25) of the registers of the Klais organ from 1928. The instrument has its own console , which is embedded in the baroque west choir stalls, from which the organ on the north wall can also be played.

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Coupling : III / I, II / I, III / II, III / P, II / P, I / P.

- Playing aids : 3 free combinations, 2 free pedal combinations, hand register to combination, tutti, tongues down, 16 'down, 32' down, register swell, roller off, coupling in roller off.

Transept organs (south pore and north wall organs)

The south pore organ is located on the south pore, one of the two so-called chorets in the crossing, which separate the crossing to the north and south like a rood screen. Together with the north wall organ - as a transept organ - it forms the main work of the entire organ system. The transept organ does not have its own play area. The south pore organ consists for the most part of registers from Kemper, while the north wall organ mainly houses parts of the older Klais organ. Part of the work also includes the cardinal trumpet , which Killinger / Breitmann installed in the guard house in the north transept in 2003.

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

East choir organ

The east choir organ, newly built in 1960, was not installed in the conche , i.e. the apex of the east apse, for monument protection reasons , but on the top left and right in the so-called imperial boxes. This instrument is mainly used to lead the congregation chant and to accompany the liturgy in the east choir. It has 34 stops on two manuals and a pedal. The game table is located on the south wall of the east choir with a view of the nave. The east choir organ houses trumpet and fanfare registers in all works, which radiate horizontally into the room.

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main gaming table

All sub-organs can be played from the six-manual main console (manual information in brackets for the individual organs).

- Coupling : II / I, III / I, IV / I, V / I, VI / I, III / II, IV / II, V / II, VI / II, IV / III, VI / V, I / P, II / P, III / P, IV / P, V / P, VI / P.

- Playing aids : 4 free combinations, 2 free pedal combinations, 3 swell kicks, crescendo roller.

New building plans

Due to the difficult acoustics in the cathedral, which results from the many additions (especially the Gothic rows of chapels, see above story), playing the organ in the cathedral is a greater challenge. The reverberation of every note played is over six seconds; the organist only hears the notes played in the east from the central console with a short delay.

Considerations

Because of these acoustic difficulties, a new nave organ ( swallow's nest organ ) was repeatedly considered. The corresponding considerations began as early as 1986. After the new cathedral organist, who was obliged to do so in 2010, had also approved a new concept, eight organ-building workshops were invited in 2012 to submit corresponding concepts. The guidelines provide for the undoing of Kemper's additions, which were regarded as inferior in quality and out of date in terms of sound, and to allow an organ system to sound again in the cathedral with a uniform, late-romantic sound color based on the Klais organ from 1928. While the organ part in the west choir is to be tailored to the choir accompaniment in the future, the main work is to be accommodated in the imperial boxes of the east choir, i.e. the location of the current east choir organ. A new building is planned at the Marien Altar east of the market portal as a connecting element to guide the parish chant and to bridge the echo effect from west to east. In the course of the redesign, the cathedral organ is also to be equipped with the digital setter that is now mandatory, which allows the organist to quickly switch between a large number (previously only four analogue combinations) of preprogrammed register combinations.

Concrete planning

In accordance with this basic concept, a consortium of organ builders Goll (Lucerne) and Rieger (Schwarzach) presented a plan that the diocese published and intends to implement in November 2017. An organ system consisting of just three instruments is planned. The new organ system is to grow from 114 registers (7,986 pipes) to 206 registers (14,526 pipes). Each instrument should have its own console, and a movable "concert console" should be built; It should be possible to play the entire system from all gaming tables.

The east choir organ is to function as the main organ in the future. With 95 stops on six manual works and a pedal, it will be the largest instrument.

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Couple

The new west choir organ is mainly intended to be an accompanying instrument for the church music set up in the west choir (choirs, wind instruments and orchestra). It is said to have 62 stops on three manual works and a pedal. In this instrument the old Klais organ from 1928 is to be resurrected; 48 existing stops of the Klais organ are to be used in this instrument; nine registers of the Klais organ from 1928 are to be reconstructed.

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Couple

The new organ in the Marienkapelle , the first side chapel east of the market portal, is to have 49 registers on three manuals and a pedal. In the future, this instrument should act as a connecting element and lead the congregation singing.

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Couple

Organ of the Gotthard Chapel

The organ of the Gotthard Chapel was installed in 1983 by the Oberlinger organ building company. Your location is the upper floor of the chapel. The purely mechanical instrument has 13 stops on two manual works and a pedal.

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Coupling : II / I, I / P, II / P.

- Effect register: Zymbelstern

Bells

history

Sources from the early days of the church bells at Mainz Cathedral are not available. A source from 1705 names 25 bells on the west tower, but another listing from 1727 only mentions 13 bells, four in the west tower and nine in the east tower. Only this source also contains a more detailed list of the individual bells. Before the east tower was destroyed during the bombardment in 1793, the parish bells hung in the east tower and the collegiate bells in the west. A precisely defined chime , which has been handed down in the sacristy book of Albrecht von Brandenburg, determined which bells were to be rung when.

In the catastrophic fire of 1767, the bells of the west tower were destroyed. The Mainz cathedral chapter immediately commissioned the casting of four new bells. In 1774 they were lifted into the west tower. As early as 1793, the cathedral caught fire again as a result of imperial troops bombarding the city, which was then occupied by the French. The fire destroyed all of the bells in the cathedral with the exception of the Bonifatius bell , which fell on the vault and tore. The cathedral had no bells for 16 years.

Today's bell

|

No. |

Surname |

Casting year |

Foundry, casting location |

Weight (kg) |

Nominal ( HT - 1 / 16 ) |

| 1 | Martinus | 1809 | Josef Zechbauer, Mainz | 3550 | b 0 -3 |

| 2 | Maria | 2000 | c 1 -3 | ||

| 3 | Albertus | 1960 | F. W. Schilling, Heidelberg | 1994 | d 1 -3 |

| 4th | Willigis | 1607 | it 1 –3 | ||

| 5 | Joseph | 1809 | Josef Zechbauer, Mainz | 1050 | f 1 -3 |

| 6th | Boniface | 550 | g 1 -3 | ||

| 7th | Bilhildis | 1960 | F. W. Schilling, Heidelberg | 548 | b 1 -3 |

| 8th | Holy Spirit | 2002 | Ars Liturgica, Maria Laach | 274 | d 2 -1 |

| 9 | Lioba | 1960 | F. W. Schilling, Heidelberg | 147 | f 2 -3 |

The basis of today's cathedral bells is formed by the four-part ensemble of the Mainz bell founder Josef Zechbauer (b 0 –c 1 –e 1 –g 1 ). After long negotiations, the Bishop of Mainz, Joseph Ludwig Colmar , managed to procure the material for casting new bells in 1809. Napoleon gave him 20 hundredweight of bronze for this, which came from captured Prussian cannons. Colmar originally planned to manufacture three bells weighing 100, 80 and 60 centimeters. Finally, it was decided to cast four new bells. They were cast in the cloister of the cathedral in September 1809. The last Elector of Mainz, Karl Theodor von Dalberg, donated 70 Spessar oaks for the belfry to be newly constructed . The belfry has been preserved.

It is not clear where the two bells came from, which were named when the cathedral bells were recorded during the First World War in 1917 and when they got into the cathedral tower. One of the bells was lost in World War I and the other in World War II .

In 1960, the decision was made to purchase four more bells to add the cathedral bell. The Heidelberg foundry master Friedrich Wilhelm Schilling was entrusted with the task. In addition, he corrected the sound of three bells of the Zechbauer peal; he retuned the former e 1 bell a semitone higher to f 1 . The bell cage from 1809 had to be expanded to accommodate the new bells, whereby the old bells remained in their historical wooden yokes. On July 2, 1960, the four new bells were consecrated by Bishop Albert Stohr. In 2002 a new bronze bell in a Schilling rib from Ars Liturgica was cast in the Maria Laach monastery. The cathedral bell is the most extensive bell in the diocese today.

Ringing order

The chime of the cathedral includes twelve different combinations. All nine bells ring at pontifical offices and on high feasts. The first eight bells ring at pontifical requests, and bells 1, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8 for pontifical Vespers each time in the church year (Advent, Lent, Easter, annual cycle) varies. As a rule, bell 4 (Willigis) rings for the Angelus , followed by bell 8 (Holy Spirit) in the evening in memory of the deceased. On the highest festivals of the church year, the largest bell (Martinus) rings at noon for the Angelus.

The dimensions of the dome

- Overall length: 109 m inside, 116 m outside

- Length of the central nave: 53 m

- Width of the central nave: 13.60 m

- Height of the central nave: 28 m

- Width of the nave (without chapels): 31.55 m

- Width of the side aisles (light): 6.51 m - 6.56 m

- Diameter of the trikoncho in the west (from north to south): 24.25 m

- Height of the west tower: 83.50 m (with weathercock)

- Clear height of the east dome: 38 m

- Clear height of the west dome: 44 m

- Height of the eastern stair tower: 55.50 m

Others

In 1184, Emperor Barbarossa celebrated his sons' sword training in Mainz Cathedral on Whitsun . The accompanying festival, the Mainzer Hoftag from 1184 on the Maaraue , went down in history as the largest festival of the Middle Ages .