Sack of Şamaxı

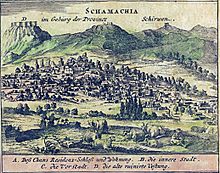

The sack of Şamaxı occurred in 1721 when Sunni rebels from the Lesgier people attacked the capital of what was then the province of Shirvan (today's Republic of Azerbaijan ). The originally successful measures to protect the city were broken off by the Persian troops, so that the unprotected city was taken by 15,000 Lesgian fighters, who massacred the Shiite population and plundered the city.

Russian traders were also killed when the city was sacked. This provided the pretext for Russia to start the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723) , as a result of which Persia had to cede large areas along the Caspian coast to Russia . Trade between Russia and Persia came to a standstill and the Volga trade route ended in Astrakhan .

prehistory

At the beginning of the 18th century, the once brilliant Safavid empire was in decline. There were uprisings and rebellions all over the country, and the will of the Shah was no longer obeyed. Shah Sultan Hosein was a weak ruler who wanted to be more humane and tolerant than his supreme mullah , but always followed the recommendations of his advisers in important state matters. Aside from occasional hunting trips, he stayed near his capital, Isfahan, and showed himself only to the closest courtiers. Since he had no idea what was really going on in the country, he relied on the top religious scholars , in particular Muhammad Bāqir al-Majlisī , in government affairs . This had already had significant political influence under Sultan Hosein's predecessor, Sulaiman I. He initiated the persecution of Sunni and Sufi residents, but also the persecution of the non-Muslim minorities of Persia such as the Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians , whereby the Christians, mainly Armenians, were less exposed to repression than the other minorities. Sultan Hosein himself showed no personal enmity towards the Christians, but under the influence of Shiite clergymen, especially al-Majlisī, he issued “unjust and intolerant decrees”. The religious tensions at the end of the Safavid period contributed greatly to the revolts by Sunnis in several areas of the empire. Shirvan was an example of this, as it was here that Sunni clergymen were killed, religious writings destroyed and Sunni mosques turned into stables.

The Sunnis in the northwest of what was then Persia, in the provinces of Shirvan and Dagestan , were severely affected by persecution during the reign of Sultan Hosein. In 1718 incursions of the lesgians into Shirvan became more frequent, with rumors circulating that the lesgians were incited to do so by Grand Vizier Fath-Ali Khan Daghestani . The Russian ambassador to Persia, who was in Şamaxı in 1718, reported that the local rulers called the Grand Vizier an unfaithful, considered his orders to be invalid and questioned the Shah's authority. The Italian Florio Beneveni, who worked in the Russian diplomatic corps, reported that the residents of Şamaxı revolted against the government because it raised large sums of money from them. The raids, incursions and looting continued, in April of the same year the Lesgians took the village of Ak Tashi near Nizovoi after kidnapping 40 villagers on the road to Şamaxı and robbing a caravan . There are also numerous reports of the rebel activities afterwards.

Attack and looting

At the beginning of May 1718, about 17,000 Lesgians stayed about 20 kilometers from Şamaxı, where they plundered settlements. In 1719, the commander-in-chief for Georgia was Vakhtang VI. tasked with opposing the Lesgier rebellion. He marched with his troops and support from Kakheti and Shirvan towards Dagestan and was able to stop the Lesgier; in the winter of 1721 he was suddenly called back at the crucial moment of the campaign. This order came after the fall of Grand Vizier Fath-Ali Khan Daghestani at the instigation of the eunuchs at the royal court, who were of the opinion that a successful end to the campaign would do more harm than good to the Safavid Empire. They feared that the Wālī Watchtang VI. could forge an alliance with Russia to join forces against Persia. At the same time, in August 1721, Shah Sultan Hosein released the Daud Khan, rebellious prince of the Lesgians and Sunni cleric, also known as Daud Beg, Haji Daud or Haji Daud Beg, from dungeon in the Safavid city of Derbent . This decision was made shortly after the Afghan invasion of the Persian heartland. Sultan Hosein and his government had hoped that Daud Khan and his Dagestani allies would help them fight the rebellion in the east of the empire. Instead, Daud Khan headed a multi-tribal alliance with the aim of fighting the Safavid troops and Shiite residents, ultimately moving against the trading town of Şamaxı.

Shortly before the siege, the Sunnis in the province of Shirvan had asked the Ottoman Empire for help against the Safavids, the archenemies of the Turks. The Lesgin tribal association with 15,000 fighters, to whom Surkhay Khan had now joined from the sheets , began to besiege Şamaxı on August 15, 1721. After Sunni city residents opened one of the city gates for the besiegers, thousands of Shiite residents, including the city administrators, were massacred while Christians and foreigners were "only" robbed. Some Russian traders were also killed. The shops of numerous Russian traders were looted, causing them great damage. The amount of the damage is given as half a million rubles or 70,000 to 100,000 tomans , claims that the Russians lost 400,000 tomans are to be viewed as exaggerations in order to have a reason for war. Damages of 60,000 tomans are said to be realistic. Among the damaged traders was Matwei Ewreinow, allegedly the wealthiest trader in Russia, who is said to have made huge losses. The Safavid governor and his relatives were "chopped into pieces by the mob and thrown to the dogs." After the province was completely taken by the rebels, Daud Khan turned to the Russians to ask for protection and declared his allegiance to the tsar. He was rejected. His second attempt to obtain protection from the Ottoman Empire was successful. He was appointed Ottoman governor for Shirvan by the Sultan.

consequences

Artemi Wolynski told Tsar Peter the Great that Russian traders had been badly damaged. He stated that this event represented a clear violation of the Russian-Persian trade treaty of 1717, because Persia had committed itself in this treaty to the protection of Russian citizens on Persian territory. Volynsky urged the tsar to attack Persia on the pretext of restoring order as an ally of the Shah. Russia used the attack on its merchants in Şamaxı as an excuse to start the Russo-Persian War in 1722 . Trade also came to a standstill, and the Volga trade route ended in Astrakhan .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Rudolph P. Matthee: The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History, 1500-1900 . Princeton University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-691-11855-0 , pp. 27 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Michael Axworthy: The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant . IB Tauris, 2010, ISBN 978-0-85772-193-8 , pp. 42 .

- ^ A b c d Roger Savory: Iran Under the Safavids . Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-04251-2 , pp. 251 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Rudi Matthee: Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan . IBTauris, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84511-745-0 , pp. 223 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Rudi Matthee: Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan . IBTauris, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84511-745-0 , pp. 225 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Firuz Kazemzadeh: Iranian relations with Russia and the Soviet Union, to 1921 . In: Peter Avery, Gavin Hambly and Charles Melville (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Iran . tape 7 . Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0-521-20095-0 , pp. 316 .

- ↑ a b c d Rudolph P. Matthee: The Politics of Trade in Safavid Iran: Silk for Silver, 1600-1730 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-64131-9 , pp. 223 .

- ^ E. Nathalie Rothman: Brokering Empire: Trans-Imperial Subjects between Venice and Istanbul . Cornell University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0-8014-6312-9 , pp. 236 .

- ^ A b Martin Sicker: The Islamic World in Decline: From the Treaty of Karlowitz to the Disintegration of the Ottoman Empire . Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, ISBN 978-0-275-96891-5 , pp. 47 .

- ↑ a b c Muriel Atkin: Russia and Iran, 1780-1828 . University of Minnesota Press, 1980, ISBN 978-0-8166-5697-4 , pp. 4 .

- ^ A b c d Martin Sicker: The Islamic World in Decline: From the Treaty of Karlowitz to the Disintegration of the Ottoman Empire . Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, ISBN 978-0-275-96891-5 , pp. 48 .

- ↑ a b c d Rudi Matthee: Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan . IBTauris, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84511-745-0 , pp. 226 .

- ↑ Michael Axworthy: The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant . IB Tauris, 2010, ISBN 978-0-85772-193-8 , pp. 62 .

- ↑ Rudolph P. Matthee: The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History, 1500-1900 . Princeton University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-691-11855-0 , pp. 28 .

Coordinates: 40 ° 38 ′ 1.7 " N , 48 ° 38 ′ 12.3" E