Populist party

The Populist Party was a short-lived political party in the United States in the late 19th century (1891-1908) and was officially called the People's Party . It was particularly well received by farmers in the western United States, largely due to their opposition to the gold standard . Although the party did not remain a permanent part of the political landscape, many of its positions were adopted by others over the decades that followed. The term “ populist ” has been a generic term in US politics ever since and describes a policy that is aimed at the common people in opposition to established interests.

history

founding

The "Populist Party" grew out of the peasant revolt that developed from the 1870s onwards. The collapse in agricultural prices and general deflation created major problems, especially for smallholders. Despite the large population growth, the money supply did not increase due to the gold standard ( de facto valid, not yet de jure). Bankers used this shortage of money for high interest rates, just as the railroad companies used their oligopoly for high transport charges. The farmers could therefore not afford the loans they needed to modernize agriculture (new equipment due to the industrial revolution). At the same time, the farmers distanced themselves from the government, which, contrary to the farmers' proposals, stuck to the previous monetary policy and did not dissolve oligopolies / monopolies. This resulted in an extensive organization of the farmers in the Farmers' Alliance with around 400,000 members nationwide in 1889, whereby, after the initial racist conflicts, the poor situation of black farm workers was increasingly discussed.

The Farmers' Alliance , formed in Lampasas in 1876 , supported collective economic action by farmers and achieved widespread popularity in the South and the Great Plains . The Farmers' Alliance gave the farmers a stronger position vis-à-vis suppliers and banks. The Farmers' Alliance, however, was ultimately unable to achieve its far-reaching economic goal of collective economic action against brokers, railways and traders due to its tight finances, and many in the Movement advocated changes in national politics. By the late 1880s, the Alliance had developed a political agenda that required regulation and reforms in national politics, most notably the contradiction of the gold standard to counter deflation in agricultural prices.

The impetus to found a new political party out of the movement arose from the refusal by both established parties, Democrats and Republicans , to take up and support the policies advocated by the Alliance, especially with a view to the populists' call for unlimited duration Minting of silver coins. The promotion of silver as legal tender has been particularly favored by farmers as a means of counteracting deflation in agricultural prices and facilitating the flow of credit in the rural banking system.

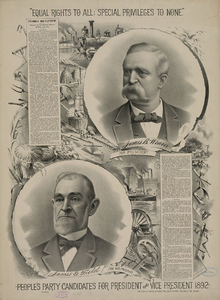

The populist party was formed in 1889–1890, by members of the Alliance along with the Knights of Labor . The movement peaked in 1892 when the party held a meeting in Omaha, Nebraska and nominated candidates for national election.

Program and promotion

The party platform called for the abolition of national banks, a tiered income tax , direct election of senators ( 17th Amendment to the United States Constitution ), public administration reform, and an eight-hour workday. In the 1892 presidential election, James B. Weaver received 1,027,329 votes. Weaver won four states ( Colorado , Kansas , Idaho , and Nevada ) and also got votes from Oregon and North Dakota .

The party flourished best among farmers in the Southwest and the Great Plains, and made significant gains in the South, where it faced an arduous struggle against the entrenched Democratic monopoly. Resistance to the gold standard was particularly strong among farmers in the West: Here its deflationary effect was conspiratorially interpreted as an instrument of the interests of high finance on the east coast , which, by instigating " credit crunches ", cause mass bankruptcies among farmers in the West could. These suspicions were sometimes anti-Semitic . Many farmers, led by the populists, rallied in the belief that "easy money" not backed by a hard mineral standard would flow more freely through rural areas. The "free silver" program received widespread support across class boundaries in the Mountain States , where the economy depended heavily on silver mining. The populists were the first political party in the United States to actively involve women in its affairs. In many southern states they strove to include African Americans. At a time when white supremacy cultural attitudes permeated all aspects of American life, a number of southern populists, most notably Thomas E. Watson , spoke of the need for poor blacks and poor whites to “racially differentiate” their "racial differences" in the name of shared economic interests Put aside self-interests.

Decline

In 1896 the Democrats adopted many of the populists' demands at the national level and the party began to decline in national popularity. The racism widespread in the country also turned out to be problematic for the populists , which arose from reservations about the Populist Party (in which blacks also played a leading role), which the Democratic Party was able to use to lure the peasants away. In the US presidential election in 1896, Democratic candidate William Jennings Bryan supported the populists' opposition to the gold standard in his famous "Cross-of-Gold" speech: at the Democratic Party's nomination convention on July 9, 1896, he proclaimed that he would did not help "to crucify humanity on a cross of gold ", for which he was enthusiastically celebrated by the delegates. The populists could not persuade themselves to also nominate Bryan's wealthy vice-presidential nominee and instead nominated Thomas E. Watson for the office of vice-president. Bryan lost to William McKinley by 600,000 votes. In the 1900 presidential election the weakened party nominated a list of Wharton Barker and Ignatius Donnelly candidates for the presidency , while many voters from among the populists supported Bryan again . Thomas E. Watson was the populist candidate for the presidency in the 1904 and 1908 elections, after which the party ceased to exist effectively.

About 45 members of the party sat in Congress between 1891 and 1902. These included six U.S. Senators: William A. Peffer and William A. Harris of Kansas , Marion Butler of North Carolina , James H. Kyle of South Dakota , Henry Heitfeld of Idaho , and William V. Allen of Nebraska .

Legacy

The nation maintained the gold standard until 1973, a fact some (but by no means all) economic historians blamed for the banking crisis during the "Great Depression". In addition, the call of the Populist Party for direct senatorial elections in 1913 was implemented with the ratification of the 17th Amendment to the US Constitution. The party's call for public administration reform became part of the Progressive Party's program (1912) .

According to historian Lawrence Goodwyn, the populist movement created a “culture of cooperation, self-respect and economic analysis” in the countryside at that time, but it did not succeed in spreading this movement in urban areas (which is also a reason for the decline was). Although the populists' political power was short-lived, they enacted and promoted important political practices such as term limits and secret elections. The populists were also responsible for their support for grassroots political movements, initiative, referendum and recall.

See also

literature

- William A. Peffer : The Passing of the People's Party . In: The North American Review . Volume 166, No. 494 , January 1898, p. 12-24 ( online from Cornell University ).

- State Executive Committee of the People's Party of North Carolina (Ed.): People's Party Hand-Book of Facts. Campaign of 1898 . Raleigh 1898 ( online from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill ).

- Goodwyn, Lawrence. 1978. The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America . Oxford: Oxford University Press. ( ISBN 0-19-502416-8 or ISBN 0-19-502417-6 )

- Kazin, Michael. 1995. The Populist Persuasion: An American History . New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-03793-3 .

- Roscoe Coleman Martin: The People's Party in Texas: A Study in Third Party Politics. University of Texas Press, Austin 1970, ISBN 978-0-292-70032-1 .

- McMath, Robert C. Jr. 1993. American Populism: A Social History 1877-1898 . New York: Hill and Wang; Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 0-8090-7796-5 .

- Nugent, Walter TK 1962. The Tolerant Populists: Kansas Populism and Nativism . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Jeffrey Ostler: Prairie Populism: Fate of Agrarian Radicalism in Kansas, Nebraska and Iowa, 1880-92. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence 1993, ISBN 978-0-7006-0606-1 .

- Stock, Catherine McNicol. 1996. Rural Radicals: Righteous Rage in the American Grain . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3294-4 .

Web links

- Populist America ( July 3, 2011 memento in the Internet Archive )

supporting documents

- ↑ https://brewminate.com/a-history-of-the-populist-peoples-party-1891-1908/

- ↑ populist . In: Oxford English Dictionary . Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- ^ A b Howard Zinn: A People's History of the United States . Harper Perennial, New York 2005, ISBN 0-06-083865-5 , pp. 283-286.

- ^ "I will not help to crucify mankind upon a cross of gold". Larry Schweikart: Populism. In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . ABC Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver and London 2003, Vol. 2, pp. 589 f .; Joseph E. Uscinski and Joseph M. Parent: American Conspiracy Theories. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, p. 111.

- ↑ Goodwyn, quoted in: Howard Zinn: A People's History of the United States. Harper Perennial, New York 2005, p. 293