Priestley Riots

The Priestley Riots ( German : "Priestley riots"), also known as the Birmingham Riots of 1791 , were politically and religiously motivated riots in the English city of Birmingham . They began on the evening of July 14, 1791 and did not end until the military arrived in Birmingham on the evening of July 17, 1791 to restore order. The riots were mainly directed against the dissenters , especially the politically and theologically controversial Joseph Priestley . Both local and national controversies fueled the mood of the rioters, from the dispute over Priestley's books in the public libraries to the dissenters' pursuit of unrestricted civil rights and their support for the French Revolution .

The riots began with an attack on the Royal Hotel , where a banquet was held on the afternoon and evening of July 14, 1791 to mark the second anniversary of the French Revolution . Subsequently, beginning with Priestley's church and house, the insurgents attacked or burned four Dissenter chapels, 27 houses and several companies. Many of the rioters had gotten drunk on alcohol that had fallen into their hands during looting or that was used to keep houses from setting alight. The riots were also directed against the property of those suspected of supporting the dissenters, including members of the scientific Lunar Society founded and directed by Erasmus Darwin .

Although the riot was not initiated by the government of Prime Minister William Pitt , the government was slow to respond to requests for help from the dissenters. Local officials appear to have been involved in planning the riot and were reluctant to pursue the ringleaders later. Industrialist James Watt later wrote that the riots had split Birmingham into two camps of deadly hatred. Many of those attacked left Birmingham immediately after the riots or in the following years. Joseph Priestley and his family first moved to Hackney near London and in 1794 emigrated to Pennsylvania.

Historical background

Birmingham

The Corporation Act of 1661 and the Test Act of 1673 had positive effects on Birmingham. Dissenters from the rest of the country forced their way into trade or industry because they were denied government office. Birmingham at the time had no city charter granted by a royal charter , so that dissenters could hold city offices here and were drawn from other English cities. Many of the dissenters lured to Birmingham in this way demonstrated great entrepreneurial skills and achieved wealth.

During the 18th century, Birmingham was notorious for its civil unrest. Dissenters and their churches were attacked as early as 1714 and 1715 during the Jacobite uprisings in Birmingham. Between 1743 and 1759, Wesleyans and Quakers were the target of occasional attacks. During the London Gordon Riots , which were directed against Catholics, numerous demonstrators also gathered in Birmingham in 1780. In 1766, 1782, 1795 and 1800 high grain prices led to riots without a religious background.

Up until the late 1780s, Birmingham's upper class did not appear to be affected by religious tension. Dissenters and Anglicans seemed to live side by side in harmony, working in the same civic associations, jointly pursuing scientific interests in the Lunar Society, and working together in the city administration. They faced together what they viewed as the rebellious plebs .

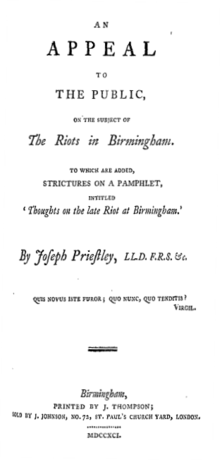

Nevertheless, after the riots , Joseph Priestley stated in his appeal An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the Birmingham Riots that the cooperation was in fact not as friendly as it was generally accepted. Priestley revealed that there had been clashes over the public library, Sunday schools, and civic office that had divided Dissenters and Anglicans. In his 1816 posthumously published publication Narrative of the Riots in Birmingham (German: "Report on the riots in Birmingham"), the publisher and historian William Hutton Priestley agreed and named five reasons for the riots: Disagreement about the inclusion of Priestley's writings in the local library; concern over the Dissenters' attempts to repeal the Corporation Act of 1661 and the Test Act of 1673; theological controversy (with a major contribution from Joseph Priestley); a seditious pamphlet; and the banquet to celebrate the French Revolution.

The Test Act and the Corporation Act restricted the civil rights of Catholics and dissenters. As a matter of principle, they were barred from office in church or state, including careers in the military and parliamentary seats. At universities, as in Oxford , they were completely excluded or, as in Cambridge , they could not obtain degrees. When the dissenters in Birmingham began to stand up for the repeal of discriminatory laws, the apparent unity among the city superiors waned. Unitarians like Priestley were at the forefront of the campaign, which led to growing unrest and anger among Orthodox Anglicans . From 1787 the emergence of groups of dissenters, who had come together exclusively to abolish these laws, began to divide the citizenship. Several attempts to have the laws repealed failed in 1787, 1789 and 1790. Priestley's support for the repeal of the test acts and his dissenting and widely publicized religious beliefs outraged the Anglican establishment. A month before the riots, Priestley tried to found the Warwickshire Constitutional Society, a political group that would campaign for universal suffrage and short legislative periods. Although the attempt failed, the attempt to set up such a group contributed to tensions in Birmingham.

Beyond the different religious and political views, the economic success of the middle-class dissenters fueled the resentment of the lower and upper classes. The steadily growing prosperity of industrialists and merchants and their gain in power linked to economic success aroused feelings of envy among members of the other classes. Priestley himself had published a pamphlet in 1787 in which he described how one could finance relief for the poor through compulsory contributions by the workers, and in which he objected to a minimum rate for assistance. His debts collection made himself as unpopular with the poor as William Hutton, another leading dissenter involved in foreclosures on small debts.

British reaction to the French Revolution

A public debate about the French Revolution took place in Great Britain, which dragged on from 1789 to 1795 as "Revolution Controversy". Initially, many people on both sides of the Canal assumed that the French Revolution would develop like the English “ Glorious Revolution ” of the 17th century. A large part of the British population was positive about the French Revolution. The storming of the Bastille was celebrated because French absolutism was to be replaced by a democratic form of government. In the early days, the supporters of the revolution believed that the British political system would also be reformed, through an extension of the electoral law and a reorganization of the constituencies, which would lead to the abolition of the " Rotten boroughs ".

The state philosopher Edmund Burke published his work Reflections on the Revolution in France (German: "On the French Revolution. Considerations and treatises") in 1790 , in which he supported the French nobility and so opposed his colleagues from the liberal Whigs . After that, pamphlets in opposition to or support for the French Revolution appeared in quick succession. Because Burke had previously supported the American colonists in their war of independence , his position on the French Revolution received a lot of attention. While Burke supported the aristocracy , the monarchy and the Anglican Church, liberals like Charles James Fox stood on the side of the revolutionaries and stood up for individual freedoms, citizenship and religious tolerance. Radicals like Joseph Priestley, William Godwin , Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft fought for a republican order, agrarian socialism or the abolition of manorial rule. The British historian Alfred Cobban described the dispute as perhaps the last real discussion about political foundations in Great Britain.

In February 1790, a group of activists came together in Birmingham who not only turned against the concerns of the dissenters, but also opposed what they believed to be an undesirable importation of French revolutionary ideals. The Dissenters tended to support the revolution and saw the constitutional monarchy enforced in France in 1791 as a model for Great Britain. The Priestley Riots took place less than a month after fleeing to Varennes , when the hopes originally aroused by the French Revolution had faded, but before the start of the reign of terror in France.

Escalation in July 1791

A gala banquet was prepared for July 14, 1791 at the local Royal Hotel to celebrate the storm on the Bastille . Whether and to what extent Joseph Priestley was involved in the planning and preparation of the event is controversial. On July 11, 1791, a note appeared in the Birmingham Gazette that a banquet to commemorate the outbreak of the French Revolution would be held on July 14, the second anniversary of the storm on the Bastille. All “friends of freedom” are invited, and tickets for the closed event can be purchased at the hotel reception. Dinner was scheduled for three in the afternoon.

The announcement in the newspaper was accompanied by a threat: next to it was a note that “an authentic list” of all participants would be published after the banquet. Also on July 11th, an ultra-revolutionary leaflet was circulated by John Hobson , the authorship of which was initially unknown. The city administration offered a reward of 100 guineas for references to the author , but could not identify him. The dissenters were compelled to deny their involvement and to publicly reject the leaflet's radical ideas. As early as July 12th there were rumors that there would be riots on July 14th. The banquet should be canceled because of the tense situation, but the owner of the Royal Hotel had already made all the preparations and insisted on the event. On the morning of July 14th, slogans against the " Presbyterians " and for "Church and King" were posted on walls in the city . At this point, Priestley was convinced by concerned friends to stay away from the banquet for safety reasons.

July 14th

81 intrepid supporters of the French Revolution attended the banquet. It was run by James Keir , an Anglican industrialist and member of the Lunar Society. When the guests arrived between two and three in the afternoon, they were expected by around 60 to 70 demonstrators, who temporarily dispersed and shouted slogans against the “papacy”. When the banquet ended around 7 or 8 p.m., a crowd of hundreds had gathered. Most of the rioters were recruited from the Birmingham workforce, they threw stones at the guests and ransacked the hotel. The crowd then moved towards the Quaker meetinghouse until someone shouted that the Quakers never got into quarrels. Instead, the Priestley Church should be attacked. The new Unitarian church was burned down, the old church looted, and the street furniture burned.

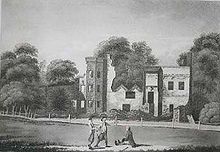

Joseph Priestley's Fairhill home in Sparkbrook was the next destination. Priestley had little time to get to safety and he fled to relatives in the surrounding area during the riots and then to London. The son, William Priestley, had stayed with others to protect the family home. However, they were overwhelmed and the house ransacked and razed to the ground. Priestley's precious library, science laboratory, and manuscripts were lost in the flames. Shortly after the events, Joseph Priestley described the beginning of the attack on his home, which he observed from a distance:

“It was remarkably quiet, we could see quite a long way in the bright moonlight, and from the top we could clearly hear what was going on in the house, every call from the crowd, and almost every blow from the tools with which they smashed doors and furniture. But they couldn't find a fire even though someone offered two guineas for a lighted candle because my abandoned son had been so careful to put out all the fires in the house and some of my friends made the neighbors do the same. Later I heard that they had tried unsuccessfully to start a fire with my large electrical device in the library . "

July 15th, 16th and 17th

The Earl of Aylesford attempted to counter the mounting violence on the morning of July 15th. Despite the support of other justices of the peace, he was unable to disperse the crowd. On July 15, the mob released prisoners from the city jail. Thomas Woodbridge, the prison director, enlisted several hundred citizens, but many of them joined the uprising. The crowd destroyed Baskerville House, the home of John Ryland, and drained the liquor in the basement. When the newly appointed constables arrived during this looting, they were attacked by the crowd and disarmed, one was killed. Other insurgents burned Bordesley Hall, the home of banker John Taylor. The local justice of the peace and the police refrained from further action against the insurgents and only read the Riot Act after the arrival of the military on July 17th.

The merchant William Russell and the publisher William Hutton tried to defend their homes, but the men they hired refused to take action against the angry masses. Hutton later wrote that he had been a rich man on the morning of July 15, and that he was ruined in the evening. Samuel Galton , owner of a factory, Quaker and member of the Lunar Society, could only save his house by bribing the insurgents with beer and money.

The rioters targeted the homes and property of individuals at all times. Detached houses like that of Joseph Priestley or the new Church of the Dissenters were burned down. The old church was adjacent to a school building, only the smashed furnishings were burned on the street. When the insurgents reached Moseley Hall, a house that also belonged to John Taylor, they carefully took the resident, the widowed and frail Lady Carhampton, with all her furniture and belongings to safety before setting the house on fire. The immediate target of the rebels was only those who were in opposition to the monarchy or the Church of England and who opposed state control.

The homes of Justice of the Peace George Russell, Rev. Samuel Blyth, Thomas Lees and a Mr. Westley were attacked on July 15 and 16. On July 16, the homes of Joseph Jukes, John Coates, John Hobson, Thomas Hawkes, and the blind Baptist pastor John Harwood were destroyed or burned down. The Baptist Chapel at Kings Heath was also destroyed. By two o'clock on July 16, the rioters had left Birmingham and were moving to Kings Norton and Kingswood. The size of a group was estimated at 250 to 300 people. They burned down a farm in Warstock and ransacked a Mr. Taverner's house. In Kingswood, they burned the Dissenter's church and rectory. Meanwhile, workers from the surrounding area who had received their weekly wages and got drunk moved to Birmingham. Since the majority of the local rebels were no longer in the city, there were only minor riots.

According to contemporary reports, the last acts of violence took place around 8 a.m. on the evening of July 17th. About thirty members of the "hard core" of the insurgents attacked the home of William Withering , an Anglican who, like Priestley and Keir, was a member of the Lunar Society. Withering managed to repel the attack with hired helpers. By the time the military arrived on July 17 and 18, the rioters had dispersed, although property was rumored to have been destroyed outside Birmingham, in Alcester and Bromsgrove .

A total of four dissenting churches were badly damaged or burned down. 27 houses and several shops were attacked, many of them looted or burned down. Beginning with the attack on the participants of the banquet in the Royal Hotel on July 14th, the mob had turned against dissenters of all directions and against the members of the Lunar Society in the name of “Church and King”.

Aftermath and litigation

Priestley and other dissenters initially blamed the government for the unrest, assuming it was caused by William Pitt and his supporters. In fact, the riots were likely organized by local officials. Some of the insurgents acted in a coordinated manner and appear to have been led by local officials, leading to allegations of planned action. Some dissenters have been warned hours or even days before the attacks on their homes. Therefore, it is likely that a prepared list of targets existed. The "disciplined core of the rioters" comprised only about thirty people who remained sober during the rioting. In contrast to hundreds of others, they did not allow themselves to be deterred from the destruction with alcohol or money.

If Birmingham's Anglican elite had planned the attacks on the Dissenters, it was more than likely that Benjamin Spencer, a local pastor, Joseph Carles, a justice of the peace and landowner, and John Brooke, a lawyer, coroner and under-sheriff, were involved were. Despite being present when the riot broke out, Carles and Spencer made no attempt to stop the rioters, and Brooke appears to have led them to the Church of the Dissenters. Witnesses agreed that the magistrate had promised protection to the insurgents as long as they attacked the dissenters' churches and meetinghouses and spared people and private property. The magistrate refused to arrest insurgents and released those who had already been arrested. Brooke handed over to the Home Office a few weeks after the riot a number of documents and letters from Priestley's possession that had been stolen when his home was ransacked. They served as evidence against Priestley and led to searches of his publishers in Birmingham and London.

Local authorities were reluctant to follow orders from the national government to persecute the ringleaders. When forced to do so, they intimidated witnesses and turned the trials into a farce. Only 17 of the fifty rioters charged were tried, four were sentenced to death, one of whom was pardoned, one banished to Botany Bay and two hanged. Priestley and others believed that these convicts were sentenced not for their involvement in the riot but as "pawn sacrifices" and for other crimes.

Although he was forced to send troops to pacify Birmingham, King George III showed himself . very pleased that Priestley has to bear the consequences of his heresies and that the people have seen through him. The Crown forced the residents of Birmingham to compensate those whose property had been damaged. The indemnity was £ 23,615, but the payout dragged on until 1797 and most of those affected received significantly less than the value of their lost possessions.

After the riots, Birmingham was split into two camps of deadly hatred, according to industrialist James Watt . First, Priestley wanted to go back to town and give a sermon, “Father, forgive them; because they don't know what they are doing ”keep. He was convinced by friends to give up the sermon because they thought it was too dangerous. Priestley wrote in his book, An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the Birmingham Riots : "Appeal to the public on the subject of the riots in Birmingham":

“I was born an Englishman as were any of you. Despite the restrictions on my civil rights, as a dissenter, I have long contributed to the support of the government and accepted that my inherited property is under the protection of its constitution and its laws. But I have been deceived, and so it will happen to you, too, if you, like me, with or without a reason, find the misfortune of being exposed to popular anger. Because then, as you have seen in my case, without a trial, with no reference to your crime or threat from you, your homes and all of your property will be destroyed, and you might not be as lucky as I was with him Life to come of it. In comparison, what are the old French Lettres de Cachet or the horrors of the demolished Bastille ? "

The riots made it clear that the leaders of the Anglicans in Birmingham were not opposed to acts of violence against the dissenters whom they saw as possible revolutionaries. They also had no concerns about sending a potentially uncontrollable mob onto the streets. Many of those attacked left Birmingham. Joseph Priestley moved with his family to Hackney near London and finally emigrated to Northumberland in Pennsylvania in 1794. One consequence was that after the unrest there was a much more conservative climate in the city, and the situation of dissenters in the city had deteriorated significantly. The remaining supporters of the French Revolution decided not to have a banquet to celebrate the stumble on the Bastille the following year. In the following years there were repeated minor riots against dissenters, for example in December 1792 in Birmingham and Manchester. Until 1795, the attacks against individual dissenters, also in the form of long-lasting threats and intimidation, continued in several other English cities.

Web links

- A Sorry End: The Priestley Riots , Revolutionary Players, Central England Industrial Revolution website, accessed April 14, 2014.

literature

- Bernard M. Allen: Priestley and the Birmingham Riots . In: Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society , Volume 5, Number 2, 1932, pp. 113-132, ISSN 0082-7800 .

- Grayson M. Ditchfield: The Priestley Riots in Historical Perspective . In: Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society , Volume 20, Number 1, 1991, pp. 3-16, ISSN 0082-7800 .

- William Hutton: The life of William Hutton, including a particular account of the riots at Birmingham in 1791 , Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, London 1816, digitized .

- without author: An Authentic Account of the Late Riots in the Town of Birmingham and its Vicinity (...) , TP Trimer, Birmingham 1791.

- Joseph Priestley: An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the Riots in Birmingham , J. Thompson, Birmingham 1791, Internet Archive .

- Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 . In: Past and Present , Volume 18, Number 1, 1960, pp. 68-88, doi : 10.1093 / past / 18.1.68

- Robert E. Schofield: The Enlightened Joseph Priestley. A Study of His Life and Work from 1773 to 1804 , The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA 2004, ISBN 0-271-02459-3 .

- Arthur Sheps: Public Perception of Joseph Priestley, the Birmingham Dissenters, and the Church-and-King Riots of 1791 . In: Eighteenth-Century Life , Volume 13, Number 2, 1989, pp. 46-64, ISSN 0098-2601 .

- Edward P. Thompson: The Making of the English Working Class , Vintage, New York 1966, ISBN 0-394-70322-7 .

- David L. Wykes: 'The Spirit of Persecutors Exemplified'. The Priestley Riots and the victims of the Church and King mobs . In: Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society , Volume 20, Number 1, 1991, pp. 17-39, ISSN 0082-7800 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ George Selgin: Good Money. Birmingham button makers, the Royal Mint, and the beginnings of modern coinage, 1775-1821 , The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI 2008, pp. 127-128, ISBN 978-0-472-11631-7 .

- ^ A b c Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 70.

- ^ Robert E. Schofield: The Enlightened Joseph Priestley , 2004, p. 263.

- ^ A b c Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 71.

- Jump up ↑ Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, pp. 70-71.

- ^ Joseph Priestley, An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the Riots in Birmingham , 1791, pp. 6-12.

- ^ Joseph Priestley: An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the Riots in Birmingham , 1791, pp. 11-12.

- ^ Joseph Priestley: An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the Riots in Birmingham , 1791, pp. 6-7.

- ^ Joseph Priestley: An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the Riots in Birmingham , 1791, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ William Hutton: The life of William Hutton, including a particular account of the riots at Birmingham in 1791 , 1816, pp. 158-162.

- ^ A b Daniel E. White: Early Romanticism and Religious Dissent , Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, p. 9, ISBN 978-0-521-85895-3 .

- ^ William Gibson: The Church of England 1688-1832. Unity and Accord , Routledge, London 2001, pp. 103-104, ISBN 0-203-13462-1 .

- ↑ a b c d Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 72.

- ^ Robert E. Schofield: The Enlightened Joseph Priestley , 2004, p. 283.

- ^ Edward P. Thompson: The Making of the English Working Class , 1966, pp. 73-75.

- ^ Robert E. Schofield: The Enlightened Joseph Priestley , 2004, p. 266.

- ^ Edward P. Thompson: The Making of the English Working Class , 1966, p. 73.

- ^ Robert E. Schofield: The Enlightened Joseph Priestley , 2004, p. 277.

- ^ Bernard M. Allen: Priestley and the Birmingham Riots , 1932, p. 115.

- ^ Ronald A. Martineau Dixon: Was Priestley responsible for the Dinner which started the 1791 Riots? . In: Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society , Volume 5, Number 3, 1933, pp. 299-323 ISSN 0082-7800 .

- ^ A b Robert E. Schofield: The Enlightened Joseph Priestley , 2004, pp. 283-284.

- ↑ In the original: A number of gentlemen intend dining together on the 14th instant, to commemorate the auspicious day which witnessed the emancipation of twenty-six millions of people from the yoke of despotism, and restored the blessings of equal government to a truly great and enlightened nation; with whom it is our interest, as a commercial people, and our duty, as friends to the general rights of mankind, to promote a free intercourse, as subservient to a permanent friendship. Any Friend to Freedom, disposed to join the intended temperate festivity, is desired to leave his name at the bar of the Hotel, where tickets may be had at Five Shillings each, including a bottle of wine; but no person will be admitted without one. Dinner will be on table at three o'clock precisely . In: Birmingham Gazette , July 11, 1791.

- ^ A b Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, pp. 72-73.

- ↑ a b c d e Robert E. Schofield: The Enlightened Joseph Priestley , 2004, p. 284.

- ^ Bernard M. Allen: Priestley and the Birmingham Riots , 1932, p. 116.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 73.

- ^ A b Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 83.

- ^ In the original: It being remarkably calm, and clear moon-light, we could see to a considerable distance, and being upon a rising ground, we distinctly heard all that passed at the house, every shout of the mob, and almost every stroke of the instruments they had provided for breaking the doors and the furniture. For they could not get any fire, though one of them was heard to offer two guineas for a lighted candle; my son, whom we left behind us, having taken the precaution to put out all the fires in the house, and others of my friends got all the neighbors to do the same. I afterwards heard that much pains was taken, but without effect, to get fire from my large electrical machine, which stood in the library , quoted from Joseph Priestley: An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the Riots in Birmingham , 1791, p .30.

- ↑ Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, pp. 73-74.

- ↑ a b c d Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 74.

- ^ William Hutton: The life of William Hutton, including a particular account of the riots at Birmingham in 1791 , 1816, p. 200.

- ^ A b Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 75.

- ↑ Grayson M. Ditchfield: The Priestley Riots in Historical Perspective , 1991, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, pp. 74-75.

- ↑ Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, pp. 75-76.

- ^ A b Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 76.

- ↑ Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, pp. 78-79.

- ^ Robert E. Schofield: The Enlightened Joseph Priestley , 2004, p. 287.

- ^ Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 79.

- ↑ Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, pp. 80-81.

- ^ A b Robert E. Schofield: The Enlightened Joseph Priestley , 2004, p. 285.

- ^ A b Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 81.

- ^ Robert E. Schofield: The Enlightened Joseph Priestley , 2004, p. 286.

- ^ Tony Rail: Looted Priestley and Russell Correspondence in the Public Record Office, London: Part 1 - three letters to Joseph Priestley . In: Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society , Volume 20, Number 1, 1991, pp. 187-202, here pp. 187-189, ISSN 0082-7800 .

- ^ A b Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 82.

- ^ Robert E. Schofield, The Enlightened Joseph Priestley , 2004, pp. 288-289.

- ^ Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 77.

- ^ Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 78.

- ^ Robert E. Schofield: The Enlightened Joseph Priestley , 2004, p. 289.

- ^ In the original: I was born an Englishman as well [as] any of you. Though laboring under civil disabilities, as a dissenter, I have long contributed my share to the support of government, and supposed I had the protection of its constitution and laws for my inheritance. But I have found myself greatly deceived; and so may any of you, if, like me, you should, with or without cause, be so unfortunate as to incur popular odium. For then, as you have seen in my case, without any form of trial whatever, without any intimation of your crime, or of your danger, your houses and all your property may be destroyed, and you may not have the good fortune to escape with life, as I have done .... What are the old French Lettres de Cachet , or the horrors of the late demolished Bastile , compared to this? […] , Quoted from Joseph Priestley: An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the Riots in Birmingham , 1791, pp. Viii – ix).

- ↑ David L. Wykes: Joseph Priestley, Minister and Teacher . In: Isabel Rivers, David L. Wykes (Eds.): Joseph Priestley, Scientist, Philosopher, and Theologian , Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, pp. 20-48, here p. 45, ISBN 978-0-19-921530 -0 .

- ^ A b Richard B. Rose: The Priestley Riots of 1791 , 1960, p. 84.

- ↑ David L. Wykes, 'The Spirit of Persecutors Exemplified'. The Priestley Riots and the victims of the Church and King mobs , 1991, p. 20.

- ↑ David L. Wykes, 'The Spirit of Persecutors Exemplified'. The Priestley Riots and the victims of the Church and King mobs , 1991, pp. 25-29.