Wealth (Schnitzler)

Wealth is an early story by Arthur Schnitzler , written in the summer of 1889. Two years later it appeared in four parts of the literary magazine Moderne Rundschau in Vienna .

Printing history

It was printed after Schnitzler had submitted it, without consulting the author, as he complained in a letter to Hugo von Hofmannsthal on September 11, 1891. An authorized version with changed first three of the eight chapters of the narrative appeared in the same year in the form of a separate print of the magazine by Carl Steinhardt in Vienna. This edition can only be documented in public institutions in the Schnitzler estate in the Cambridge University Library . Reinhard Urbach printed the first version in his Schnitzler commentary.

content

Count Spaun and Freiherr von Reutern allow themselves a carnival joke. The house painter Karl Weldein, a penniless drinker and gambler, is put into an elegant formal suit and seated next to the noble gamblers in the club. Weldein, who used to want to be a painter, is on a lucky streak and is making a fortune at the gaming table. The suddenly very rich, failed painter buries his fortune under a bridge next to the river, gets drunk and the next morning cannot remember the hiding place at all. He deeply regrets his poor little son and his ailing wife, who as a seamstress makes a significant contribution to the upkeep of the small family.

It took the painter twenty years to think of hiding it on his deathbed. By then the woman had long since passed away. The son Franz, now a painter - more talented than his father - digs up the treasure and acquires access to that club through Count Spaun. Franz had assured the count that he could only immortalize this gambling den in his next work of art after he had internalized the essence of this gamble by trying it out.

Franz gambled away his inherited money down to the last penny and also lost his mind. He digs under the bridge again, mistaking pebbles for pieces of gold. Count Spaun just can't believe it. In his madness, Franz has become his own father, who pities his wife, the seamstress and his little son Franz, i.e. himself.

reception

- In 1922, Hofmannsthal emphasized in a laudation for Schnitzler that the author had already emerged as an artist with wealth in his early days .

- Scheffel points to the fairytale ending, which is about Franz's self-pity: the son becomes his own father in an almost wonderful way. Everything repeats in life. Father and son both fail in this strangely circular construction. The father cannot remember the hiding place for twenty years and the son cannot create the intended work of art. In addition, the chosen social environment is on the one hand typical for naturalistic storytelling: the story ends where it begins - in misery and the father, a simple craftsman, inherits his ailments (addiction to drinking and gambling), but also his painterly talent, the son. On the other hand, Schnitzler adhered to Hermann Bahr's On the Critique of Modernity from 1890 during the above-mentioned revision , i.e. wanted to overcome naturalism when it depicts Weldein's inner life.

expenditure

- First printing: Moderne Rundschau , Volume 3, Issue 11 of September 1, 1891, pp. 385–391 Volume 3, Issue 12 of September 15, 1891, pp. 417–423 Volume 4, Issue 1 of October 1, 1891, pp. 1-7 Volume 4, Issue 2 of October 15, 1891, pp. 34-40.

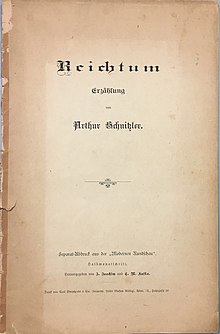

- First edition: Arthur Schnitzler: Wealth . Separate print of the Modern Rundschau. Edited by J. Joachim and EM Kafka. Printed by Carl Steinhardt & Cie (head of department Gustav Röttig), Vienna IX., Hahngasse 12. (23 pages)

- Three copies can be verified: 1) Arthur Schnitzler's estate , Cambridge, 2) Hugo von Hofmannsthal's library 3) Private property

On-line

- First edition. archive.org

- The text

literature

- Michael Scheffel : Arthur Schnitzler. Stories and novels. Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-503-15585-9 , pp. 27-35

- Schnitzler commentary on the narrative writings and dramatic works. Winkler, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-538-07017-2 ; oeaw.ac.at (PDF)

Individual evidence

- ^ Arthur Schnitzler to Hugo von Hofmannsthal, September 11, 1891, Free Deutsches Hochstift, signature Hs-30885,15. Reprinted in Hofmannsthal / Schnitzler, p. 13

- ↑ Reinhard Urbach: Schnitzler commentary on the narrative writings and dramatic works. Winkler, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-538-07017-2 , pp. 83-93; oeaw.ac.at (PDF).

- ↑ Hofmannsthal, quoted in Scheffel, p. 34, 16. Zvu

- ↑ Scheffel, p. 30, 8. Zvo

- ↑ Scheffel, p. 34, 19th Zvu

- ↑ Scheffel, p. 29, 17. Zvo

- ↑ Hermann Bahr: On the Critique of Modernity . archive.org

- ↑ Scheffel, p. 31, below

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: Library . In: Ellen Ritter †, Dalia Bukauskaité and Konrad Heumann (eds.): Complete works . tape XL . S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-10-731541-3 , p. 605 .