Ryssä

Ryssä is in Finland a historically neutral, in today's parlance but strong pejorative connotations name for Russia and the Russians , that provides a Ethnophaulismus . The standard language Finnish term for Russia is Venäjä , the associated Ethnonym venäläinen .

Etymology and change in meaning

Finnish has two names for the Russians: venäläinen (plural venäläiset ) and ryssä (plural ryssät ). Statements about its age and the historical usage of words are made difficult by the fact that Finnish only became a literary language in the 16th century through the efforts of Mikael Agricolola , but was only rarely written or even printed after that, and when it was, it was mostly for the purpose of Christian edification . Until 1902 , the only official language of Finland was Swedish , the language of the nobility and the urban bourgeoisie. The Finnish vernacular did not move into the interest of the awakening national romanticism until the middle of the 19th century, and the many folkloric works from this time, above all the works of Elias Lönnrot , documented a centuries-old oral tradition , but should be treated with caution there they are often falsified by the linguistic purism of the compilers, i.e. they represent romantic artifacts. This is especially true of Lönnrot's edition of Kalevala (1835), which is still considered the Finnish national epic today.

But it can be said with certainty that venäläinen is the older of the two names; it comes from the Finnish hereditary vocabulary and can be found similarly in the other Baltic Finnish languages, i.e. in Estonian ( venelane ), Ingrian , Karelian , Livonian , Wepsian and Wotish . It is probably originally the same word that resulted in the German ethnonym " Wenden ", which was used to generalize Slavs until the early modern times . In Finnish literature, the word first appears in 1551 at Agricola as Wehelaiset and Wenhäläiset . In the Kalevala the venäläiset are mentioned six times, the ryssät, however, not once.

Ryssä , on the other hand, is a loan word from Swedish in Finnish (cf. Swedish ryss "Russe" and Ryssland "Russia"). It corresponds to the self-designation of the Russians and Russia (русские russkije or Россия Rossija ) and the names derived from it in all other European languages (with the exception of Baltic Finnish), which in turn refer to medieval Rus and ultimately probably to North Germanic roðr "rowing, rowing team “Goes back. The oldest evidence of Finnish ryssä can be found in 1702 in the writings of the chaplain Anders Aschelinus , in 1745 he met with Daniel Juslenius , but in view of the sparse tradition of the Finnish vernacular, it cannot be ruled out that it may be a much older loan.

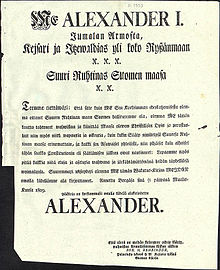

In the 19th century the two words were apparently used indiscriminately. That ryssä was initially not a negative connotation, at least shows the Finnish translation of the in French-held speech with which Tsar Alexander I in 1809 at the Diet of Porvoo to the Grand Duke of Finland Print declared and the new ruler also exceptionally in the vernacular and let it spread. Right at the beginning of his speech from the throne he describes himself here as “by the grace of God emperor and ruler over the whole of Ryssänmaa ” (ie over the “land”, Finnish maa , “the Russian”, in the wording: 'ME ALEXANDER I. Jumalan Armosta 'Kejsari ja Itzewaldias yli koko Ryssänmaan' ). Timo Vihavainen thinks it is conceivable that at that time ryssä was the more elegant word, as it was taken from the prestigious language of the time, i.e. Swedish; it may have appeared affected to the Finnish-speaking plebs for precisely this reason. Vihavainen even speculates that for this very reason, not ryssä , but, on the contrary, venäläinen may have had a coarse or contemptuous connotation. In this context he refers to a well-known folk verse ( kansanruno ) , probably dating from the time of the “ Great Unrest ”, which the folklorists of Finnish national romanticism in northern Finland encountered again and again, and in which the venäläinen is reviled as a murderous beast: “Venäläinen verikoira / tappoi ison, tappoi äidin / oisit tappanut minutkin / jos en ois pakohon päässyt / ... " in German something like " The Russian bloodhound killed my father, my mother as well, would have killed me too, had I not fled "etc.

Ryssä only turned into a swear word after Finland gained independence in 1917 and was helped by the end of press censorship that went with it. Nationalist circles stoked in the following years blatantly Russians hate , especially the student-bündische club Akateeminen Karjala-Seura (AKS), the "liberation" throughout Karelia from "Russenjoch" and the union of all Finnish tribes in a " Greater Finland sought". The title of one of his programmatic publications became a catchphrase : 'Ryssästä saa puhua vain hammasta purren' (1922), in German “You can only speak of Russians with gritted teeth.” Even today every Finn is familiar with the saying 'Ryssä on ryssä vaikka voissa paistais [i] ' , "The Russian remains a Russian, even if you stir-fry him in butter." During the Second World War, the saying , first attested in Lappeenranta around 1890 , "Yksi suomalainen vastaa kymmentä ryssää" , "a Finn was taken up against ten Russians ”, an often used propaganda formula. The couplet Silmien väliin , which Reino Palmroth recorded in 1942 during the Continuation War and which instructed the Finnish soldiers where to shoot, is also famous and notorious , namely 'silmien välliin ryssää, juu!' , so "right between the eyes of the Russian, hurray!"

Since the war, at the latest, the word has been historically heavily burdened. The Nykysuomen sanakirja (1951–1961) was content with marking the word as colloquial, all newer dictionaries mark it as derogatory or offensive, for example the Suomen kielen sanakirja from Gummerus (1996) and that from the state language institute KOTUS ( Kotimaisten kalten keskus ) published and thus quasi-official Kielitoimiston sanakirja . According to a survey from the year 2000, ryssä is currently one of the most serious ethnic or xenophobic insults in Finnish colloquial language: 92% of those surveyed rated the word as insulting, ahead of neekeri (" negro "; 90%) and mane ( " Gypsies "; 88%) took the top spot among the ethnophaulisms , hurri (a word coined for the Finland-Swedes ), mustalainen ("gypsies"), sakemanni and saku (twisting of saksalainen , i.e. "German") followed at a considerable distance and japsu (corresponds to German "Japse", ie "Japanese").

The word ryssä still appears neutral in the two compositions that have been handed down since the 18th century : ryssänlimppu ("Russian loaf ," a wholemeal rye bread) and laukkuryssä (literally "pocket Russian "; this is how the hawkers from Russia were called who continued into the early 20th century traveled through Finland every summer).

Web links

- Timo Vihavainen : Puhutaanpa correctisti , blog entry from October 3, 2013.

- Veronica Shenshin: Venäläiset ja Venälainen kulttuuri Suomessa: Kulttuurihistoriallinen katsaus Suomen venäläisväestön vaiheista autonomian ajoilta nykypäiviin . Published by the Alexander Institute of Helsinki University, hosted on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Finland website, 2008.

References and comments

- ↑ There is probably a connection with the Venetae , which Pliny locates in his Naturalis historia east of the Baltic Sea, as well as with the Venedi , which, according to Tacitus ' Germania, settled on the eastern edge of the Germanic world, in the vicinity of the Fenni , which for their part are mostly equated with the Baltic Sea Finns or the Sami .

- ↑ Veronica Shenshin: Venäläiset ja Venälainen kulttuuri Suomessa , pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Which is not surprising because Lönnrot often deleted loan words and replaced them with Finnish words (more often with their own word creations); Hardly any conclusions can be drawn from this about the actual use of language in the early modern period or the Middle Ages.

- ↑ In Finnish, however, this etymon gave the country name for Sweden, Ruotsi , which is explained by the fact that the Kievan Rus was founded by Vikings (the Varangians ) who originally lived in today's Sweden ; Ryssä and Ruotsi are therefore etymological duplicates.

- ↑ Veronica Shenshin: Venäläiset ja Venälainen kulttuuri Suomessa , pp. 25-26.

- ↑ Timo Vihavainen : Puhutaanpa korrektisti

- ↑ It should be noted that war propaganda of this kind during the Second World War came mainly from the Finnish home press, which was largely independent, whereas the authorities and the military were reluctant to do so. So it was by no means Marshal Mannerheim who called for shooting the Russian "between the eyes", as Palmroth claims in the first stanza ( 'Mannerheimi sano: Nyt sitä lähtään silmien väliin ryssiä tahtään!' ).

- ↑ Veronica Shenshin: Venäläiset ja Venälainen kulttuuri Suomessa , p. 26.

- ↑ Entry ryssä in the online edition of Kielitoimiston sanakirja , accessed on December 4, 2019.

- ↑ Satu Tervonen: Etnisten nimitysten eri sävyt , in: Kielikello, Heft 1, 2001.

- ↑ Riitta Eronen: Naapurien nimistä: kuka onkaan hurri? . In: Kielikello , issue 3, 1995.