Saavedra study

The Saavedra study is one of the most famous and influential chess studies . The chess composition , which contains only four stones , first appeared in the Weekly Citizen on May 4, 1895 as a drawing study by Georges Emile Barbier , but Fernando Saavedra discovered an opportunity for White to make a profit that Barbier had not recognized.

The study

The diagram shows the Saavedra study in the form published since 1902. Since the study was originally intended to show a way to a draw for Black, it was initially published on c7 with black move and white pawn.

At first it seems obvious that Black will only achieve a draw if he can exchange his rook for the white pawn. Variants in which the white pawn goes through unmolested lead to the endgame queen against rook , which in the cases considered here would be won for white. The variant of the Saavedra study with 6. c8D is an exception.

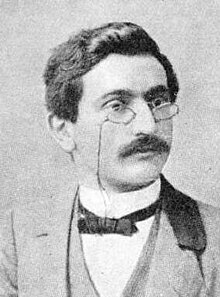

Fernando Saavedra

Weekly Citizen (Glasgow)

May 18, 1895

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

After the train

- 1. c6-c7

Black can the conversion only prevent the farmers by offering continuously Chess:

- 1.… Rd5 – d6 +

The white king can not enter the 7th row because of the pegging 2.… Rd7. Because of 2.… Rd1! 3. c8D and skewer by means of 3.… Rc1 + he is also denied the c- file . To play for profit, Weiß uses the Potter maneuver :

- 2. Kb6-b5 Td6-d5 +

- 3. Kb5-b4 Td5-d4 +

- 4. Kb4-b3 Td4-d3 +

Or 4. Kb4-c3 Rd4-d1 5. Kc3-c2 Rd1-d4! with the same result.

- 5. Kb3-c2

Now Black can no longer offer check without losing the rook. However, he can still set a stalemate:

- 5.… Rd3 – d4!

It threatens 6. ... Tc4 +, and after the sixth C8D Tc4 + 7 dxc4 Black is stalemated , as originally intended by Barbier. The moves 6. Kb3 Td3 + or 6. Kc3 Td1! 7. Kc2 Rd4 lead to repetition . Saavedra found the way to win:

- 6. c7 – c8T !!

White performs a sub-conversion into a rook and threatens mate on a8. Although there is a material balance, Black no longer has a defense. Since the rook, unlike the queen, cannot move diagonally, 6.… Rc4 + 7. Rxc4 is not a stalemate. The only defense against the impending mate is:

- 6.… Rd4 – a4

With the withdrawal of the king from the c-file

- 7. Kc2 – b3!

White now causes a double attack . The double threat of 8. Kxa4 and 8. Rc1 mate leads to black rook winning, after which White wins elementally .

In addition to the famous endgame study with the Réti maneuver , this is one of the most famous chess compositions of all.

The problem was initially published as a draw study on May 4, 1895, but a few days after the solution was published on May 11, the solver Fernando Saavedra made the author Barbier aware that a profit path was possible. Barbier then reprinted the position on May 18, this time with a claim for profit, and published the solution on May 25, 1895.

history

The authorship of the study was unknown for a long time before it could be reconstructed by the Dutch chess composer John Selman . In doing so, he relied primarily on the information provided by the eyewitness Archibald Neilson , an Irish chess player and columnist. Selman also explored the spread of the study in the early years.

Emergence

The starting point for the study was a game between Richard Fenton (white) and William Potter . In the handicap game in which Potter had given the pawn f7 and a move, after 56 moves a position arose that was agreed as a draw , although the Potter maneuver would have won. Barbier was a spectator at this game.

London 1875

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

Weekly Citizen , April 27, 1895

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

The counterparties had after 56. ... Ra6 + agreed According, or other information already in this position, draw, although the known from a study by Kling and Horwitz maneuvers would have won (see precursor ): 56. ... Ra6 + 57. Kc5 Ta5 + 58. Kc4 Ra4 + 59. Kc3 Ra3 + 60. Kb2 won, as Johannes Zukertort showed in the City of London Chess Magazine .

After Potter's death on March 13, 1895, Barbier wrote an obituary which he published on April 27, 1895. He also stated this position in the game, but with incorrect details. In particular, the pawn was now one row to the right, the king and rook had swapped lines. However, that did not affect the solution with the Potter maneuver. According to Selman, Barbier himself had incorrectly reconstructed the position from memory; later it turned out, however, that this diagram had already been given seven weeks earlier by H. W. Hawks in his column in the Newcastle Weekly Courant of March 9, 1895 as the party position.

Analyzing the position, Barbier noticed a stalemate for Black if the black king was on a1 instead of h6 as in the incorrectly reconstructed diagram. He published this position on May 4, 1895 with the task that Black should hold a draw, and rightly called it his own composition based on the game Fenton – Potter.

One of the readers of Barbier's chess column was the Spanish-born Reverend Fernando Saavedra, who solved the study between the publication on May 4, 1895 and the appearance of the solution on May 11, 1895, but looked at it again a few days later and discovered the winning move. A short time after May 11, 1895 (in a later draft article, Selman gave May 13, 1895 as a probable date for psychological reasons) Saavedra went to the Glasgow Chess Club and showed the three members present Archibald Johnson Neilson, Georges Emile Barbier and Hector Rey the profit path. On May 18, Barbier reprinted the task with the claim for a prize for White, naming Saavedra as the finder of the prize guide. On May 25th, he published the solution.

distribution

The Saavedra study became known to a broader chess public around 1902 when Richard Teichmann demonstrated it at the Monte Carlo championship and Emanuel Lasker used the task in lectures in the same year, which is why it was often awarded to Lasker. However, this gave the Glasgow Weekly Herald as the source in his lectures . In the second part of a two-part article, the Wiener Schachzeitung published the Saavedra study with the white pawn on c6 and the heading From a game of Potter - Fenton . In a footnote, she stated that Saavedra had shown winning the game position given as a draw, which was printed in the Glasgow Weekly Citizen in 1895.

On September 25, 1910 and June 11, 1911, an article written by Otto Dehler was published in the Hamburger Nachrichten (1910) and the Wiener Schachzeitung, respectively. In the article Dehler writes: The 'Wiener Schachzeitung' wants to know the name and names a Rev. Saavedra who has proven this winning lead in a game which was given a draw . In a footnote to this, Georg Marco referred to the above article when it was printed in the Wiener Schachzeitung. He also stated that Emanuel Lasker had named this as a source during a lecture at the Manhattan Chess Club. On June 15, 1929, Henri Weenink published a short article in the 50th edition of his column on well-known chess studies, in which he referred to Saavedra as the Swedish vicar. He also named the Saavedra study as a position between Potter and Fenton, but made no further references.

Research by Selman

After extensive research, John Selman succeeded in reconstructing the history of the Saavedra study. In an article published in November 1940, he described this in detail. Selman claims to have known the study for a long time, but to have found particular interest in the study in the collection of studies with submorphoses, which was started together with Cornelis Jan de Feijter and which was designed for later publications. This was mainly due to the fact that, with the exception of this study, the author was completely unknown in the chess world both as a composer and as a player. Even the source of the study was not considered certain, as various information were in circulation. Selman was puzzled by the fact that the study was supposed to be Scottish, but Saavedra is a Spanish name borne by the Don Quixote author Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra , among others . After research and a letter to the Glasgow Chess Club, which, according to Selman, turned out to be a blind-fired lucky hit, Selman was introduced to Archibald Johnson Neilson, who was present at the Glasgow Chess Club in May 1895, when Saavedra was demonstrating the win. Neilson, a long-time clerk for a chess column in the Falkirk Herald , was the first real eyewitness Selman could find. After clearing up some of the misinformation about Saavedra, Selman goes on to say that in 1875 there was a duel between the mighty William Norwood Potter and Vivian Fenton or Richard Falkland Fenton. Potter, who pretended a pawn and one or two moves, won the handicap match with five wins and four draws from nine games. One of the draw games ended as described in the story of how it came about , which Selman then cited.

After the genesis, Selman gave Saavedra's curriculum vitae and then continued with the dissemination history of the study. This was initially only known locally until 1902 world chess champion Emanuel Lasker gave lectures in Glasgow, where Neilson showed the study. After Lasker used them in a lecture on October 3, 1902, a message about the study was published in the Glasgow Weekly Herald on October 11, 1902. The pawn was moved from c7 to c6 for the first time, which meant that White should win to move. In the article, however, several errors were found, the study was presented as a position between Potter and Fenton and Reverend S. [sic!] Saavedra named as the author. The mistakes were taken over by British Chess Magazine when the composition was reprinted there, after which it was published in every chess magazine in 1902 or 1903. At the chess tournament in Monte Carlo in February 1902, however, the study was also circulating, there without any indication of the author or source. It was later attributed to Lasker, which in Selman's opinion is due to the fact that he had used the task at lectures in Glasgow and Manchester. Around 1911 Creassey Edward C. Tattersall put together his book A Thousand Endgames , for which Archibald Johnson Neilson sent him the Saavedra study, which was included in the book as number 336 and was subsequently reprinted worldwide.

Saavedra himself never asked for authorship of the task, but Neilson made sure that Saavedra's name would not be forgotten and reprinted the study several times in his column in the Falkirk Herald . Selman then finished his article with thanks to several correspondents, including Meindest Niemeijer , whose library he was allowed to use for the research.

Later research

In 1996, John Roycroft addressed two questions about the slow dissemination of the study that were left open in Selman's article. He noted that at the Hastings Grand Masters tournament in August 1895 the study was not mentioned in the tournament book, so it could be assumed that the composition was unknown among the players at the time. Roycroft lists several factors that may have prevented the study from spreading. The Weekly Citizen had few readers compared to the Weekly Herald and Neilson's Falkirk Herald . Furthermore, the publication itself took several weeks and, due to the style of writing, only looked like a correction. In addition, the sub-metamorphosis was hidden in the text and no diagram was given in the solution. Barbier fell ill in the summer, while Löser did not send corresponding letters to British Chess Magazine . The Hastings chess tournament also took up a lot of space in chess columns. The copying options were also not widespread. Finally, Neilson's column, as Selman and Roycroft noted, did not reprint the study in 1895 and its influence was believed to have been small. Thus there was no broad publication of the study between 1895 and July 1902.

The other riddle was that, according to Selman, Lasker was shown the study by Neilson in October 1902, but that Lasker allegedly showed it around at the Monte Carlo Grand Masters tournament in February and March 1902. Roycroft solved the mystery through further research and found that, although Lasker was not in Glasgow before the Grand Masters tournament, Richard Teichmann did visit Glasgow in January 1902. Roycroft quotes the Oxford Companion of Chess , according to which Teichmann rarely wrote articles, and sees this as an explanation for the fact that Teichmann did not disseminate the study before the tournament in Monte Carlo. Since Teichmann had given lectures at the Glasgow chess club for four months, someone there, but probably not Neilson, must have shown him the study. The connection to Lasker probably lies in a task that Lasker published in 1892 and whose similarity could have been significant enough for the players in Monte Carlo to suggest that Lasker was the author of the Saavedra study. While the German Chess Newspaper stated in July 1902 for the Saavedra study that the author was unknown, the German Weekly Chess on July 13, 1902 (p. 231) named Emanuel Lasker as the suspected author. On January 25, 1903, the German weekly chess corrected this information in response to a reader request that Lasker had only "wrested the study from oblivion". Roycroft notes that the column was probably referring to the well-known name Lasker, who was wrongly assigned the task, and not Lasker himself. In Roycroft's opinion, Lasker learned of the study from the publications at an indefinite point in time between July and October 1902, before Neilson had shown it to him. On October 3, 1902, Lasker used the Saavedra study in a lecture at the Glasgow Athenaeum , in which barber had also given lessons years earlier. On October 4, 1902, Lasker sailed on the Columbia ship to New York City.

source unknown (see text)

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

Solution:

1. f7 Rxe6 + 2. Kg5 Re5 + 3. Kg4 Re4 + 4. Kg3 Re3 + 5. Kf2 wins

The above position should have appeared in the London Chess Fortnightly in 1892 . However, research by Ken Whyld later revealed that the study could not be found in the specified source.

In 2006, Harold van der Heijden answered the question of how the Saavedra study was disseminated in Russia. He found out that the publication in the Deutsche Schachzeitung in July 1902 was not the oldest publication with the white pawn on c6, but was shown in Bohemia 1902.

precursor

The idea of conquering a woman who had just been transformed by a spit was already shown in 1512 by Damiano de Odemira in a study that was, however, incorrect according to later findings by Thompson. The Potter maneuver followed in 1853 in a study by Kling and Horwitz. Eugene Beauharnais Cook showed the stalemate in the Bilguer in 1864, probably after a position by Daniel Harrwitz . The white king maneuver Kc2 – b3 with a double attack, referred to by Alexander Rueb as the charged king move , was not shown before the Saavedra study.

The Chess Player 1853

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

Handbook of Chess , 4th Edition 1864

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

Solutions:

Left: 1. g6 Rxh6 2. g7 Th5 + 3. Kf4 Th4 + 4. Kf3 Th3 + 5. Kg2 wins

Right: 1. Rb7 + Kc8 2. Rb5! c1D 3. Rc5 + Qxc5 patt

Alleged anticipation

Irish Master James Alexander Porterfield Rynd claimed in the Evening Herald on May 25, 1895, the date of Barbier's publication of the solution, that the Saavedra position had appeared in one of his games. He gave the following game fragment, which was allegedly played three or four years earlier against the club president of the Dublin-based Clontarf Chess Club, William Francis Lynam. In 2001 the position reappeared when Tim Krabbé published the article "The Saavedra Myth Exposed" on his website. After the material was further published, experts argued over whether Porterfield was telling Rynd the truth.

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

1. f6 – f7 Rb5xe5 +

2. Kh5 – g4 Re5 – e4 +

3. Kg4 – g3 Re4 – e3 +

4. Kg3 – f2 Re3 – e4

5. f7 – f8T Re4 – h4

6. Kf2 – g3 and Black resigned.

The only event that would fit the description of Porterfield Rynds was a simultaneous performance on December 18, 1890, which was attended by many spectators.

The authenticity of the game has been questioned, as Porterfield Rynd published it only after it was published in the Glasgow Weekly Citizen , but it was only Roycroft in January 2002 that presented a chain of circumstantial evidence against the existence of the game. Porterfield Rynd did not publish the game promptly and only reacted relatively late to the Barbiers columns, which, as can be deduced from his reactions to earlier Barbiers columns, he read. Details and position, such as the introduction with a stroke and the relatively weak club president as an opponent, rather indicate plagiarism . Nor does Porterfield Rynd give any information on how the black king got to h1. As strong evidence, Roycroft cites that Porterfield Rynd has claimed the invention of the auxiliary mat , as well as plagiarized another study in his column on October 19, 1895 and issued it as a position. According to Ken Whyld , the price report also appeared in British Chess Magazine in July 1895 . As with the Saavedra study, Porterfield Rynd remained calm when Tattersall published the study in A Thousand Endgames in 1911 . Roycroft sees Porterfield Rynd's assertion that the Saavedra was a position in one of his games for refuted in the overall circumstances. Krabbé also noted in his Open Chess Diary that he now considers the game to be invented.

Rigaer Tageblatt 1895, 2nd prize

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

Miss Barr's Lucan Spa Hotel 1895

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

Left: White wins by 1. Bc7! Qe1 + 2. Kh2 Qxf2 3. Bd6! Qf4 + 4.g3 + Qxg3 + 5. Bxg3 mate

Right: Allegedly the game ended with 37.… Nd3 38. Qxf3 Qb3 39. Qxd3 Qxd3 40. Bf7 Qxc2 41. Ka2 f4 42. gxf4 Qc4 + 43. b3 + Qxb3 + 44. Bxb3 mate

influence

In his book The Chess Endgame Study (first edition title: Test Tube Chess ), John Roycroft calls the Saavedra study “undoubtedly the most famous of all endgame studies”.

Harrie Grondijs cites 36 further studies in No Rook Unturned (2004), which lead to a position from the Saavedra study. These appeared between 1895 and 2003, with the alleged fragment of Porterfield Rynd against Lynam being the earliest entry. Mark Saweljewitsch Liburkin combined the idea of this composition with another sub-transformation.

Schachmaty w SSSR 1931, 2nd prize

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

Solution:

1. Sa2 – c1 with two variants:

1.… Rc5xb5 2. c6 – c7 Rb5 – d5 + 3. Nc1 – d3 Rd5xd3 + 4. Kd1 – c2 Rd3 – d4! 5. c7 – c8T! Rd4 – a4 6. Kc2 – b3 wins.

1.… Rc5 – d5 + 2. Kd1 – c2 Td5 – c5 + 3. Kc2 – d3 Rc5xb5 4. c6 – c7 Rb5 – b8! 5. c7xb8L! wins

literature

- Harrie Grondijs: No Rook Unturned. A Tour Around the Saavedra Study. The Hague 2004. ISBN 90-74827-52-7 .

swell

- ↑ See the reproduction in Tim Krabbé: The Discovery of the Saavedra

- ↑ The course of the game with the handicap of Bf7 and two moves: 1. e4 2. d4 e6 3. Bd3 De7 4. Ne2 d6 5. Nc3 Nc6 6. a3 g6 7. 0–0 Bg7 8. Be3 Nf6 9. h3 a6 10. f4 d5 11. e5 Nd7 12. f5 gxf5 13. Bxf5 exf5 14. Nxd5 Qd8 15. Nef4 Ndxe5 16. dxe5 0–0 17. Qh5 Bxe5 18. Rad1 De8 19. Qh4 Rf7 20. Rfe1 Qf8 21. b4 b6 22. c4 Bd7 23.Nd3 Qg7 24. Bf4 Bxf4 25.S3xf4 Ne5 26.Nf6 + Qxf6 27. Qxf6 Rxf6 28.Rxe5 Bc6 29. Kf2 Rf7 30.Rd3 Be4 31.Rd4 Bc6 32.g3 Raf8 33.Nh5 Re8 34.Rxe8 Lxe8 35 .Nf4 Bd7 36. Nd3 Re7 37. Kf3 Kg7 38. c5 Bb5 39. cxb6 cxb6 40. Kf4 Bxd3 41. Rxd3 Rf7 42. Ke5 Kg6 43. Rd6 + Kg5 44. Rxb6 f4 45. gxf4 + Rxf4 46. Rxa6 Rxh3 48. a4 h5 49. b6 Rb3 50. a5 h4 51.Ra8 h3 52. Kd6 Kg4 53.Rh8 Rb5 54.Rxh3 Kxh3 55. Kc6 Rxa5 56. b7 Ra6 +. Draw agreed.

- ↑ Grondijs, pp. 31-32

- ↑ Edward Winter: Saavedra . Chess Notes , item 5796. October 12, 2008

- ↑ Grondijs, pp. 359-360

- ^ British Chess Magazine, November 1902, pp. 481-482. Reprinted in part in Grondijs, p. 284

- ^ Collection of all studies and endgames from the period 1900 to 1903 . Wiener Schachzeitung, edition 8/1903, August 1903, p. 189 and edition 9–10 / 1903, September – October 1903, pp. 229–230.

- ↑ Otto Dehler: The development of an endgame . Hamburger Nachrichten, September 25, 1910 and Wiener Schachzeitung 09/1911; reprinted in: Grondijs, pp. 335–338

- ↑ H. G. M. Weenink: Popular Endgame Studies (L) . Oprechte Haarlemsche Courant, June 15, 1929. Reprinted in: Grondijs, p. 339

- ↑ J. Selman Jr .: Wie what Saavedra? . Tijdschrift van de Koniklijken Nederlandschen Schaakbond 48, No. 11 (November 1940). Translated into English and reprinted in: Grondijs, pp. 344–353

- ↑ John Roycroft: John Selman and Saavedra - laying the story to rest! In: eg 122, October 1996. pp. 906–911 ( online version as PDF file)

- ↑ Ken Whyld: The collected games of Emanuel Lasker . P. 216

- ↑ Harold van der Heijden: The Jap Trick . EBUR 04/2006. Pp. 17-18

- ↑ wKg5 Rb7 Ba2 g6 sKd6 Ra6 Bc5. P. Damiano, Questo libro e da imparare giocare a scachi et de le partite 1512. White moves, Black wins. 1. g7 Rxa2 2. g8D Rg2 + 3. Kf4 Rxg8. The Thompson endgame databases, however, do not indicate a win.

- ↑ wKh4 Rg5 sKf6 Bf2. Daniel Harrwitz, textbook on the game of chess 1862. White draws and holds a draw with 1. Rg3 f1D 2. Rf3 + Qxf3 stalemate. Instead, Harrwitz only treated 1. Rg8 Kf7 with a black victory in the book.

- ↑ http://www.xs4all.nl/~timkr/chess2/prynd.htm

- ^ See for example Grondijs, p. 383

- ↑ John Roycroft: The Porterfield Rynd Affair . In: eg 143, January 2002. pp. 523–527 ( online version as PDF file)

- ^ Open Chess Diary , item 151

- ^ John Roycroft, The Chess Endgame Study . 2nd edited edition. New York 1981. pp. 90-91

- ↑ Grondijs, pp. 313-332

Web links

- The Discovery of the Saavedra (English)

- Gravestone of the Reverend Saavedra by Edward Winter