Sheaths

| Sheaths | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

White-faced sheathbill ( Chionis alba ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name of the family | ||||||||||

| Chionididae | ||||||||||

| Bonaparte , 1832 | ||||||||||

| Scientific name of the genus | ||||||||||

| Chionis | ||||||||||

| JR Forster , 1788 |

The sheaths ( Chionis ) are a genus of birds from the order of the plover-like, consisting of two species . They are the only genus in the Chionididae family .

The breeding area of the genus lies exclusively in the Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic, in the southern winter a species moves north to Patagonia . The completely white feathered, roughly chicken-sized and compactly built sheaths are the only birds in the Antarctic habitat that live exclusively on land. They are kleptoparasites that are heavily dependent on sea bird colonies . The IUCN classifies the two species as not endangered .

features

anatomy

The build of the sheaths is well adapted to the harsh environmental conditions of the Antarctic habitat. The body is stocky and compact in order to minimize heat loss through the smallest possible body surface, the feet and legs are unusually strong for birds of this size.

There is a slight sexual dimorphism between the sexes in terms of size , males are on average 15% heavier and slightly larger than females and have slightly larger beaks. The head-trunk length is between 34 and 41 centimeters, the wingspan between 74 (females of the black-faced vaginal beak) and 84 centimeters (male of the white-faced vaginal beak). The weight is between 540 grams for the females of the black-faced vaginal beak and 850 grams for the males of the white-faced vaginal beak. The toes have narrow flaps of skin.

The conical beak is very strong and a horny sheath sits at the base of the upper beak . Characteristic of both species is the bare facial skin that extends from the base of the beak to over the eyes and has warty outgrowths. There is a bulging, bare skin ring around the eyes. The horny sheath and facial skin can be used to determine the age , as these characteristics are not yet very pronounced in juvenile birds. Both sexes have a short, blunt horny thorn on the carpal bones that is used in territorial fights.

Coloration and plumage

The cover plumage of the vaginal beaks is pure white, underneath there is a very thick layer of gray down . It is unclear whether the white plumage originally evolved as an adaptation to the snowy environment, as sheaths are often found on rocky beaches; there the white plumage is again very noticeable. It may play a role in identifying conspecifics. A year after the breeding season, the plumage is in March blossomed . The moult lasts relatively long with up to 70 days. Young birds and non-breeding individuals start moulting as early as January.

Move

The sequence of movements when walking is reminiscent of that of chickens; the animals usually walk slowly around with their heads slightly lowered and nodding with every step. However, you are also capable of short sprints. It is also relatively common for sheaths to move on one leg: while one foot is pulled to the body to warm, they slowly hop around on the other foot. The flight is straight, the wings are flapped strongly, only rarely a short distance is sailed. Sheaths are capable of long flights over several hundred kilometers at a time.

voice

Sheaths give out loud, shrill calls, which are usually used to demarcate and defend a territory or to communicate with the partner during the breeding season. During the ritual threatening gestures before a territorial battle, sheaths often emit a series of sounds that can be onomatopically described as "kek kek kek kek kek". Outside of the breeding season, the birds hardly utter any sounds; birds roaming around in groups sometimes make chuckling sounds. The alarm call, which is uttered especially when skuas are sighted , is a shrill whistle.

distribution and habitat

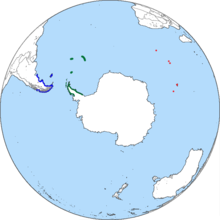

Winter: blue;

Black-faced sheath beak : red

Sheaths colonize the coastline of the Antarctic Peninsula from the northern tip to Grahamsland in the south, as well as sub-Antarctic islands from the South Shetland Islands to South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands and between the Prince Edward Islands and Heard . In South America , the coast of Tierra del Fuego and the east coast of the mainland to northern Patagonia are settled. The occurrence of sheaths is closely linked to the occurrence of colonial seabirds , especially penguins , and seal colonies . Sheaths inhabit mainly rocky coastlines and on the sub-Antarctic islands and the South American mainland also near the coast grass and bush lands and boggy areas.

Way of life

Grazing area and migration behavior

During the breeding season, the area of action is limited to that part of the sea bird colony in the immediate vicinity of the nest that is defended as breeding territory. The radius of action is limited to no more than one kilometer. Outside the breeding season, the birds search larger areas for food and sometimes move long distances along beaches. Home areas for non-breeding birds are significantly larger; these birds cover up to 30 kilometers in a day. At the onset of dusk, they look for sleeping places, which are often on rock platforms directly on the coast, occasionally rock ledges inland are also used as sleeping places.

Black-faced sheaths usually stay in the breeding area all year round and only avoid short distances in harsh weather, while white-billed sheaths move further distances after the breeding season, from March to May, and visit areas with a more moderate climate in South America. Some of them cover several hundred kilometers and overwinter mainly on the east coast of Patagonia. In exceptional cases, individual specimens have been spotted in Uruguay and southern Brazil . They return to the breeding areas towards the end of October to November. Long-distance flights usually take place without stopping, but there are also occasional flights to ice floes on which penguins or seals rest to look for food. Ships are also occasionally used as a stopover.

Activity and comfort behavior

Most of the day is spent searching for food. Sheath beaks spend one to two hours a day caring for their feathers. Often the birds bathe thoroughly before the plumage by the oils of the preen gland grease again. At higher temperatures and in sunshine, vaginal beaks take sunbaths by crouching down in exposed places with their wings slightly spread apart.

Social and antagonistic behavior

Sheath beaks often appear outside of the breeding season in groups of up to 50 animals that look for food together and sleep standing close together. The horny sheath of the beak and the warty facial skin seem to play an important role in social behavior. Individuals with larger beaks and larger outgrowths on the facial skin are the dominant animals in groups.

In the rare territorial fights during the breeding season, the animals use the thorn on the wing to hit the enemy and thus drive them away. Before doing this, however, attempts are made to drive away intruders through ritualized threatening gestures , such as violent nods of the head and crouching with slightly spread wings while the beak is chopped into the air or the ground. If none of the opponents withdraws, the birds stand up in front of each other with spread wings and show the thorns on their wings. If it comes to a fight, it usually only lasts a few seconds, during which the opponents beat each other with their wings and pull their plumage with their beak. Serious injuries are extremely rare, and fights usually end without a fight. The winner of an argument usually pursues the loser over a short distance by calling and flapping his wings strongly. Outside of the breeding season, there can be disputes over the privilege of feeding, especially on cadavers.

Natural enemies and avoidance of enemies

Adult, healthy sheaths have no enemies, but skuas prey on eggs, young birds and weakened animals. In the northern range of the genus, peregrine falcons mainly beat young birds. Open areas are avoided when skuas are nearby. In a direct attack, sheaths will usually attempt to flee to the waterline in a group. To a lesser extent, cannibalism occurs by capturing unsupervised eggs and young birds from neighboring breeding pairs. To ward off nest robbers, breeding birds spread their wings slightly and chop their beak on the aggressor while they make hissing sounds.

nutrition

Sheaths are pronounced kleptoparasites and scavengers that are highly dependent on the colonies of penguins , other seabirds and seals in their vicinity . As opportunists, they also search the rubbish for leftovers at research stations. Because of the invertebrates contained in the kelp , the birds also ingest large amounts of this alga , which they find in the flushing area , especially outside the breeding season .

In seabird colonies they prey on eggs and occasionally also newly hatched young birds. However, sheaths lurk primarily for adult birds that want to provide their offspring with food. While the food is being passed to the young bird, the sheath beak tries to pull it out of the adult bird's beak or to distract it by flapping around and chopping in front of its beak. Smaller penguins and cormorants are occasionally knocked over in order to get to the food. Captured eggs are chopped up with the beak and, like captured young birds, are usually brought to the nest before they are eaten. Seal colonies are mainly visited during the settling time, the sheaths often eat the afterbirth . In penguin colonies, sheaths also eat fresh droppings, as these still contain a relatively large amount of nutrients. In seal colonies, vaginal beaks drink milk by pushing their beak between the teat and mouth of the drinking cub. Away from colonies and outside the breeding season, vaginaries usually search for food along the flushing line and then mainly eat invertebrates. They rarely move a few hundred meters inland to look for food in wetlands. The birds pull smaller plants out of the ground in order to discover animals hidden in the roots, and they also rummage through areas of loose earth with their beak. Bones with remains of meat from washed up whales and seals are pressed to the ground with their feet, and the beak is used to tear off and scrape off chunks of meat. A long-lasting snow cover outside the breeding season of seabird colonies can lead to starvation, especially young and weak birds, as there is a lack of food available from colonies and the flushing border does not offer enough food.

Reproduction

Pair formation

From the age of three to four, young sheaths begin to look for a partner and to defend breeding grounds. However, first breeders are often not successful. The percentage of non-breeding birds is relatively high, fluctuating between 30 and 40 percent. Sheaths are largely monogamous, and pairs breed together every year. Separations usually only occur when a brood is unsuccessful. The courtship, which is also carried out with long-term couples, consists of rhythmic nods of the head of both partners while equally rhythmic croaking calls are uttered. This ritual is also performed as a greeting.

The brood is mostly closely tied to the reproductive cycle of the seabird colonies that are nearby. Couples often defend a breeding area as early as November, which usually includes part of a seabird colony and is aggressively defended by the males, but also the females. In colonies of smaller penguin species and other seabirds, an area contains between 40 and 200 seabird breeding pairs, as these are easier to rob than king penguins, for example, of which a sheath-beak breeding area usually contains 200 to 400 breeding pairs.

Outside the breeding season, when the seabird colonies are deserted, sheaths often give way to still active colonies of king penguins . There they often defend smaller territories and sometimes develop seasonal relationships with partners with whom they do not breed. These partnerships and winter territories are given up again before the start of the breeding season.

Nest building and nest location

The nest is a simple hollow on a hill made of grass, moss, algae, feathers and found bones. It is created in a cave or under a ledge and is often located in or in close proximity to a colony of sea birds. Sheaths take over abandoned burrows from other birds, but never dig their own den. Nest locations near which penguins nest are preferred, as these offer additional protection against skuas through the defensive behavior of the penguins.

Clutch and brood

As soon as the breeding business begins in the seabird colonies, usually mid to late December, the sheaths also lay their clutch. This consists of two to three pear-shaped eggs, in exceptional cases only one or up to four eggs. The basic color of the eggs is creamy white, they are gray or brownish mottled. There is an average of four days between the laying of the individual eggs; the clutch is incubated after the first egg is laid. Both sexes participate in the hatching business and take turns warming the eggs about every one and a half to two hours.

The young birds hatch after a breeding season of 28 to 32 days in mid to late January, shortly after the majority of the young birds in the sea bird colony have hatched. Between 60 and 85 percent of the eggs are hatched successfully. Since there are several days between the laying of eggs, the young birds hatch at different times. As a result, the first young bird has a better chance of survival if only little food is available. Usually only the first hatched young bird survives, the other young birds often starve to death or are eaten by skuas because of their weakness. After hatching, the chicks can already after a few hours crawl around in the nest, however, at least two more weeks by parents brooded . About 30 days after hatching, the young birds begin to leave the nest and roam around in the vicinity. Hatchlings have dense brown down feathers that are replaced by gray down after one to two weeks. The first white feather feathers appear after about 14 days. After an average of 50 days, the white plumage of an adult bird is fully developed. The young birds fledge towards the end of March and from this point on they look for food independently, but follow their parents for up to six months. Breeding pairs that do not breed near penguin colonies have a lower reproductive success, with an average of 0.7 young birds per brood, than breeding pairs that have access to penguin colonies. These have an average of 1.1 young animals per brood. Both adult birds feed the offspring with their beak, but they do not choke out a food pulp like seabirds. The majority of the food of the young birds consists of fish mash and krill, which the adult birds have captured by kleptoparasitism in sea bird colonies and transport to the nest in their beak.

Systematics

The sheaths probably developed from plover-like ancestors in southern South America. The exact position of the Chionididae family within the plover species is, however, controversial. In the past, based on morphological and behavioral studies, a relationship with the high altitude runners was assumed, as well as with the Skuas . Chemotaxonomically , the genus was temporarily placed in the vicinity of the seagulls in the past . Recent genetic studies seem to support a closer relationship between the sheaths and the triels and a close relationship with the magellan plover.

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

The genus includes only 2 species:

- White-faced sheathbill ( Chionis alba ), no subspecies

- Black- faced sheathbill ( Chionis minor ), four subspecies

Sheaths and human

Due to their largely remote and inhospitable range, the habitat of the sheaths only overlaps with that of humans in a few places. The birds are curious and not scared, they steal unsupervised food from researchers and tourists, and also examine pens, shoes and other items for food suitability. There are often numerous sheaths' beaks near research stations and in ports. The food supply in these places has meant that some birds no longer move to climatically more favorable areas in the southern winter, but rather live on food remains from human settlements during this time.

At the beginning of the 20th century, sheaths were hunted by whale and seal hunters, who called them "ptarmigan" because of their appearance and which they served as food. Nowadays, sheaths are no longer hunted.

Persistence and protection

Population figures are difficult to determine because of the inaccessible location of the breeding areas, but BirdLife International assumes a population size of more than 10,000 breeding pairs of the white-faced vagabill and 6,000 to 10,000 breeding pairs of the black-faced vaginal beak. The populations are divided into many small subgroups, with only a few dozen pairs breeding on many small Antarctic and sub-Antarctic islands. The vaginal beaks are classified as not endangered by the IUCN .

According to the IUCN, the populations are not endangered, but small populations on sub-Antarctic islands can be harmed by neozoa such as mice, rats and cats introduced by humans , as they eat eggs and young birds. There may also be a risk of disease transmission from chickens kept on some islands. Sheath beaks are potentially at risk due to their low reproduction rate of around one young bird per breeding pair and year. Strong falls in the stock can only be compensated for very slowly. Due to the strong dependence of the sheaths on seabird colonies, their population size is directly linked to their occurrence. If the population of a seabird colony collapses, the population of sheaths in the region also goes out.

swell

literature

Much of the information in this article is taken from:

- Josep del Hoyo , Andrew Elliot, Jordi Sargatal: Handbook of the birds of the world - Volume 3, Hoatzin to Auks . Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 1996, ISBN 84-87334-20-2 .

The following sources are also used:

- Hadoram Shirihai: A Complete Guide to Antarctic Wildlife - The Birds and Marine Mammals of the Antarctic Continent and Southern Ocean . Alula Press, Degerby 2002, ISBN 951-98947-0-5 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Chionis in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011. Accessed January 5, 2011.

- ↑ Jürgen Jacob: Chemotaxonomic classification of the sheaths (Chionidae) in the bird system. In: Journal of Ornithology. Vol. 18, No. 2, 1977, pp. 189-194.

- ↑ A. Baker, S. Pereira, T. Paton: Phylogenetic relationships and divergence times of Charadriiformes genera: multigene evidence for the Cretaceous origin of at least 14 clades of shorebirds. In: Biology Letters. Volume 3, No. 2, 2007, pp. 205-210.

- ^ GH Thomas, MA Wills, T. Székely: A supertree approach to shorebird phylogeny. In: BMC Evolutionary Biology. Volume 4, No. 28, 2004.

- ↑ TA Paton, AJ Baker, JG Groth, GF Barrowclough: RAG-1 sequences resolve phylogenetic relationships within charadriiform birds. In: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. No. 29, 2003, pp. 268-278.

- ^ BC Livezey: Phylogenetics of modern shorebirds (Charadriiformes) based on phenotypic evidence: analysis and discussion. In: Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. Volume 160, No. 3, 2010, pp. 567-618.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2011) Species factsheet: Chionis albus. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org/ on 09/02/2011. Recommended citation for factsheets for more than one species: BirdLife International (2011) IUCN Red List for birds. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org/ on 09/02/2011

- ↑ BirdLife International (2011) Species factsheet: Chionis minor. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org/ on 09/02/2011. Recommended citation for factsheets for more than one species: BirdLife International (2011) IUCN Red List for birds. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org/ on 09/02/2011

Web links

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Chionis alba in the Internet Bird Collection

- Videos, photos and sound recordings on Chionis minor in the Internet Bird Collection

- xeno-canto: sound recordings - Snowy Sheathbill ( Chionis albus )

- xeno-canto: Sound recordings - Black-faced Sheathbill ( Chionis minor )