Battle of Cape Esperance

| date | October 11. bis 12. October 1942 |

|---|---|

| place | Cape Esperance , Pacific |

| output | allied victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 4 cruisers , 5 destroyers |

3 cruisers , 2 destroyers |

| losses | |

|

1 destroyer sunk, |

1 destroyer sunk, |

The Battle of Cape Esperance (also known as The Second Battle of Savo Island ) took place in World War II during the Pacific War at the entrance of the road between Savo Island and Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands on October 11, 1942.

background

The battle was a consequence of the battle for Henderson Field airfield . On October 11, the Japanese sent forces under Rear Admiral Goto Aritomo to bomb the Henderson airfield and reinforce the Japanese ground forces . Two combat units were formed for this purpose. The seaplane carriers Chitose and Nisshin transported the troops together with six destroyers and were to arrive late in the evening off Guadalcanal and begin unloading. Admiral Goto himself wanted to arrive around midnight with three heavy cruisers and two destroyers and bombard the airfield.

American scouts spotted the Japanese ships on the approach. As a result, Task Force 64 under Rear Admiral Norman Scott set out to intercept them. Knowing that the Japanese had advantages in night combat, Scott planned to use his destroyers to illuminate targets with searchlights and destroy them with shell fire .

Battle formation

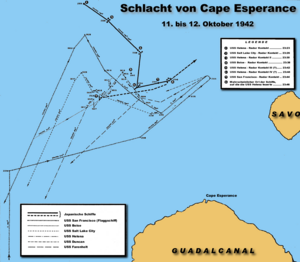

Scott's formation circled Guadalcanal south and, coming from the south, reached the western entrance of Ironbottom Sound . Without knowing it, he pushed himself between the Japanese reinforcement group, which had already entered the Ironbottom Sound, and the bombing group that was still on the march. The American formation was a simple keel line. In the lead were the destroyers USS Fahrenholt , USS Duncan and USS Laffey , followed by the heavy cruisers USS San Francisco and USS Salt Lake City and the light cruisers USS Boise and USS Helena . The destroyers USS Buchanan and USS McCalla formed the end .

Admiral Goto's formation consisted of the heavy cruisers Aoba , Furutaka and Kinugasa running in the keel line . The destroyers Fubuki and Hatsuyuki ran on both sides of the leading cruiser . The reinforcement group did not take part in the following battle.

course

At 11:30 p.m., the Japanese met Task Force 64, which the Japanese spotted earlier using their radar . Admiral Scott ordered his keel line to change course to the southwest in order to carry out the Crossing the T maneuver before the incoming Japanese, but by mistake his flagship , the San Francisco , turned at the same time as the destroyer driving the column , instead of the Laffey in front of her consequences. Since the rest of the ships followed the San Francisco , the American unit now consisted of two columns, the main group formed by the cruisers and the rear destroyers and the second column consisting of the front three destroyers, which was now located between the American cruisers and the Japanese and tried to sit down in front of the American cruisers again at increased speed. In order to prevent his forward destroyers from coming into the cruisers' line of fire, and because he did not quite trust the new radar technology, Scott hesitated a while before giving the order to fire. At 11:46 p.m. the American cruisers finally opened fire on the Japanese ships about 6.5 nautical miles (12 kilometers) away .

The Japanese were completely surprised by the fire attack. They had sighted the American ships shortly before, but thought they were units of their own reinforcement group. American fire was focused on the lead cruiser, Goto's flagship Aoba , which received multiple hits, including fatal injuries to Admiral Goto. The Japanese formation then broke up when the individual ships turned unauthorized to avoid enemy fire. The Kinugasa and the Hatsuyuki turned to port, with which they went on the opposite course to the American unit and the distance to the enemy quickly increased. However, Aoba , Furutaka and Fubuki turned to starboard and thus went on a parallel course with the enemy, who continued to subject them with massive fire. In terms of artillery, Task Force 64 was far superior to the Japanese unit, with a total of 19 20.3 cm and 30 15.2 cm guns on the American cruisers, compared to only 18 20.3 cm guns on the Japanese cruisers . The Furutaka tried to attract the American fire and divert attention from the badly damaged Aoba . The Furutaka itself was devastated by massive fire from the American cruisers San Francisco , Boise and Helena , so that it sank at 12:40 a.m. The badly hit Fubuki sank shortly after the start of the battle. However, the Furutaka's sacrifice saved the flagship and enabled the other Japanese ships to escape back through the strait.

During the fight, the Boise also received two hits from the Kinugasa's 8-inch guns, exploding ammunition in the forward turrets, killing 107 sailors in turrets 1 and 2. The destroyer Duncan tried to carry out a single-handed torpedo attack, but began to burn after several hits and was then accidentally shot at and badly damaged by its own cruisers.

At 12:20 a.m., the fight was over. The Boise was saved by floods, which put out most of the fires. The Duncan was abandoned at two o'clock. At 3 o'clock a leak prevention squad from the McCalla boarded the Duncan again and tried to bring the damage under control by noon. But when the main deck was flooded, the Duncan was left to her fate.

The American victory led to wrong conclusions. The Crossing the T tactic worked at Cape Esperance, but later skirmishes such as the Battle of Tassafaronga or the Battle of Kolombangara showed that at night the lightning bolts from the gunfire illuminated the ships, revealing their position, making them vulnerable to torpedo attacks .

literature

- Samuel Eliot Morison : The Struggle for Guadalcanal. August 1942 - February 1943 . Little-Brown, Boston MA 1948 ( History of United States naval operations in World War II , 5). An Atlantic Monthly Press Book.

- Eric LaCroix, Linton Wells: Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War . US Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD 1997, ISBN 0-87021-311-3 .

- Mark Stille: USN Cruiser Vs IJN Cruiser. Guadalcanal 1942 . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2009, ISBN 1-84603-466-3 ( Duel , 22).

Web links

- Detailed text on ibiblio.org (English)

- Info (english)

Individual evidence

- ↑ USN Cruiser Vs IJN Cruiser: Guadalcanal 1942, page 68