Naval battle in the Strait of Otranto

| date | May 15, 1917 |

|---|---|

| place | Straits of Otranto and Adriatic Sea |

| output | Austro-Hungarian victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 3 rapid cruisers 1 armored cruiser 4 destroyers 3 submarines |

3 light cruisers ~ 10 destroyers 47 drifters |

| losses | |

|

2 rapid cruisers damaged |

1 light cruiser badly damaged |

The naval battle in the Strait of Otranto on May 15, 1917 was the largest naval battle in the Adriatic during the First World War . It developed out of a night attack by three rapid cruisers of the Austro-Hungarian Navy on the drifters that were maintaining the network locks of the Otranto lock . Due to the disagreement of the involved Allied commanders and fortunate circumstances, the company, led by the liner captain Miklós Horthy , could be ended successfully and without major losses, whereas the Allies lost several ships. The battle changed little in the overall strategic situation of the naval war in the Adriatic.

prehistory

The Otranto Barrage was set up after the war, Italy's entry in May 1915 mainly on British ships to ward off the passage of submarines into the real Mediterranean. It consisted of driftnets patrolled by destroyers and later mine barriers and was initially maintained by around 60 British drifters. Later the number of blocking ships increased to over 100, of which at least 50 should be at sea at all times. The Strait of Otranto is about 70 kilometers wide at its narrowest point, so that each drifter had to guard more than a kilometer. The effectiveness of the lock was poor; Thus, during the entire war, only one Central Powers submarine (the Austrian U 6 ) was known to be lost at the barrier, possibly two more.

The lock was nonetheless disruptive enough that the Austro-Hungarian Navy, which was trapped in the Adriatic, undertook about 20 nightly disruptive actions and raids on it from 1915 to 1917. The largest of these raids until May 1917 was an attack by six Huszár-class destroyers in December 1916, which, however, was unsuccessful. It was only by chance that two French destroyers rammed an Italian one in pursuit.

planning

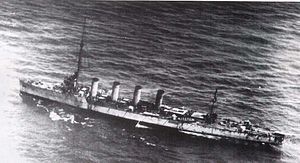

The plan for another attack seems to have been devised by Horthy, the commander of the light cruiser Novara , who had previously attracted attention for his daring and enterprising spirit. Together with the sister ships Helgoland and Saida , they should undertake an attack on the blocking ships and destroy as many as possible before sunrise, in order to then start the quick march back to Cattaro . The ships were to leave at nightfall, then separate and attack different sections of the barrier. After the end of the attack, the three ships should meet 15 nautical miles from Cape Linguetta by 7.15 a.m. at the latest and run back together. Their appearance was changed by replacing the mast, among other things, so that they resembled large British destroyers.

As a diversion, three Tátra-class destroyers were to carry out a simultaneous attack on Allied ships on the Albanian coast. This should confuse the Allies as to the location of the attack and the units involved. However, only two destroyers, Csepel and Balaton , were actually operational. Furthermore, three submarines were used: the Austrian boats U 4 and U 27 were to operate off Valona and Brindisi , respectively , the German UC 25 also lay mines off Brindisi. The armored cruiser Sankt Georg with two destroyers and several torpedo boats would be ready for remote support. In addition, the Budapest liner with three other torpedo boats was kept ready for emergencies. Planes from Durazzo and Kumbor would be flying reconnaissance missions.

course

Attack on the Drifters

The attack by the three cruisers on the blocking ships began around 3:30 a.m. on May 15, after the ships had successfully evaded an Italian-French destroyer patrol. The plan to confuse the Allies worked perfectly. So initially no alarm was raised. In addition, a few minutes earlier the destroyer group from Csepel and Balaton had attacked an Italian supply convoy escorted by the destroyer Borea and sunk the destroyer and an ammunition ship, as well as setting fire to another ship, which was abandoned.

The attack lasted until after sunrise. The drifters, armed with individual 4-pounders or 57-mm guns, had nothing to counter the cruisers, each armed with nine 10-cm cannons. By the time the attack ceased, 14 of 47 drifters had been sunk and four others were damaged, three of them seriously. The Austrians warned the crews of the small ships with signals before they opened fire from a short distance so that the sailors could still get to safety. Occasionally, however, the drifters also returned fire, which is why a captain was awarded a Victoria Cross after the battle . Over 70 men of the crews were taken as prisoners of war by the Austrians.

Allied countermeasures and battle of pursuit

At around 4:35 a.m., the Italian Rear Admiral Alfredo Acton , who had meanwhile been alarmed, ordered the patrol north of the barrier (the flotilla leader Carlo Mirabello and four French destroyers) to come to the aid of the drifters and make contact to establish the enemy ships. Acton himself set sail with the light cruiser Dartmouth at around 5:30 am, followed by the Bristol and the Italian flotilla leader Aquila and the four destroyers Mosto , Pilo , Schiaffino and Acerbi .

Later, around 8:30 a.m., the Italian reconnaissance cruiser Marsala left with the flotilla leader Carlo Racchia and the Indomito-class destroyers Insidioso , Indomito and Impavido .

The Mirabello group with Commandant Rivière , Cimeterre and Bisson had arrested the Austrian ships at around 7 a.m., but were kept at a distance by their guns and shifted to shadowing the formation. The three French destroyers had trouble following the Austrian ships due to machine problems.

Around 7.45 a.m., the Dartmouth and her escort ships stopped the Csepel and Balaton , but did not immediately realize that they were only destroyers. A chase developed at high speed, which was prematurely ended by a machine hit on the flotilla leader Aquila around 8:30 a.m. The Austrian destroyers thus safely reached the protection of the coastal batteries at Durazzo. However, the cruisers Horthys were still south of the main Allied group and were still shadowed by the Mirabello group. Around 9 o'clock smoke was reported on the stern of the Bristol and Acton ordered a U-turn.

The main battle began, in which the British cruisers with their 15 cm guns were artillery superior to the Austrians. A disadvantage for the Allies was that several ships had to be parked to protect the wrecked Aquila . The Mirabello and the French destroyer Rivière also had to stop temporarily with engine problems. The Bristol was also too slow to keep up with the Dartmouth , and its four-inch guns were too short for combat. In addition, the Austrian naval aviators were very active and shelled the Allied ships with machine guns and bombs.

In the meantime the group around the cruiser Marsala had also appeared, and Admiral Dominique Gauchet had dispatched three other French destroyers from Corfu . From Valona, where an Italian flotilla leader was with several destroyers, however, no ship ran out because Acton did not request assistance. The Austrians had sent the Sankt Georg with her escort ships to support Horthy

The Austrian cruisers also suffered from machine problems. The Saida only ran a maximum of 25 knots and slowed down her sister ships. So the Dartmouth could stay within reach for a long time. After a 6-inch shell from the Dartmouth killed part of the Novara bridge crew including the first officer, Horthy put a smoke screen and slowed down to get the Dartmouth under his cannons. The Dartmouth was hit several times, but Horthy himself almost fell victim to his maneuver at around 10:10 when he was hit by shrapnel and fell unconscious for some time. At around 11 a.m., Acton slowed down to give the Bristol a chance to catch up. This probably saved the Novara , which lost speed after being hit by an engine and finally had to stop completely. When St. George's smoke plume appeared on the horizon , Acton turned to join the Marsala group that was still behind. This gave the Austrians enough time to tow the Novara .

When the Saint George drew closer, it was too late for Acton to sink the Novara . The armored cruiser had, among other things, two 24 cm guns and was thus able to successfully deter the lighter Allied cruisers. Several Italian ships, including the Marsala , overlooked Acton's first withdrawal signal and attempted attacks, but at around 12:05 p.m. Acton ordered the final withdrawal.

The Austrians finally united with the destroyers Csepel and Balaton and started the march back to Cattaro with the Novara in tow. On the way they even met the Budapest with their escort, so that they had practically nothing to fear. They were given a triumphant welcome in Cattaro.

On the march back of the Allies, who also had two ships in tow, the Dartmouth was torpedoed by UC 25 at around 1.30 p.m. and could only be brought back to port with great difficulty after the submarine had been chased away by depth charges. The French destroyer Boutefeu , which left Brindisi to support the cruiser, ran into one of the mines previously laid out by UC 25 and sank.

Result and consequences

Despite the damage to the Rapid cruisers, the Austrians were able to book the battle as a victory, as they had inflicted significantly higher losses on the Allies, especially due to the sensible approach of their submarines. In addition, with their diversionary attack they had captured an Allied ammunition convoy and severely decimated it.

Due to the attack, the British naval command decided that in the absence of adequate destroyer protection, all drifters had to leave the Otranto Barrier at night. Destroyers were chronically inadequate for the Allies in the Adriatic. The Drifters could only stay at the lock for about 12 hours a day.

Strategically, the battle had little effect on the situation in the Adriatic. The Otranto barrier was almost ineffective anyway, and submarines of the Central Powers were usually able to pass through it with ease, both before and after. The number of drifters only decreased temporarily and was increased again by the arrival of the US fleet in European waters. The main fleets with their capital ships remained outside the battle and continued to neutralize each other.

literature

- Paul G. Halpern: A Naval History of World War I. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis 1995, ISBN 1-55750-352-4 .

- Ders .: The Battle of the Otranto Straits: Controlling the Gateway to the Adriatic in WWI. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 2004, ISBN 0-253-34379-8 .

- KMA - KuK Kriegsmarine Archive (ed.) - The sea battle in Otranto Street on May 15, 1917, Vienna 2017