Sepiola rondeletii

| Sepiola rondeletii | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sepiola rondeletii ( Sepiola rondeletii ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Sepiola rondeletii | ||||||||||||

| Leach , 1817 |

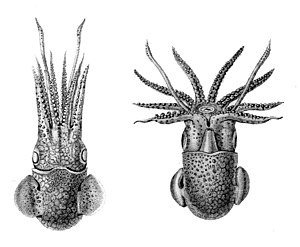

Sepiola rondeletii , also known as the Mediterranean cuttlefish or dwarf cuttlefish , is a species of dwarf squid found in the Mediterranean and Eastern Atlantic . The red-brown to black colored, a few centimeters large species can usually be found near the ground and feeds predatory.

This small animal was officially first described and identified by William Elford Leach in 1817 and is also known by the following names: Loligo Sepiola Blainville, 1828; Sepiola desvigniana Gervais & Van Beneden, 1838; Sepiola grantiana Férussac, 1834; Sepiola rondeleti Leach, 1817; Sepiola vulgaris Grant, 1833; Sepia sepiola Linnaeus, 1758. The latter name fulfills all criteria to be considered a " nomen oblitum ".

Its closest relative is Sepiola atlantica . It differs from this one in that it has a corrugated abdominal edge and a different number of suction cups: Sepiola atlantica has four rows of suction cups on the tip of the lower arms and two rows on the other arms. Sepiola rondeletii , on the other hand, has only two rows of suction cups on all arms.

Sepiola rondeletii is not classified as an endangered species, but its exact population size is unknown.

Distribution and habitat

Sepiola rondeletii comes from a. in the Mediterranean and the Eastern Atlantic. Their north-south distribution extends from the North Sea to Senegal. The distribution area Mediterranean also includes the Strait of Sicily , the Aegean Sea , the Adriatic Sea , the Marmara Sea and the Levantine Sea .

Sepiola rondeletii lives close to the sea floor, preferably on muddy and sandy substrates or in seagrass meadows. So far, there have been sightings both in shallow water and at depths of up to 450 m.

Anatomy, appearance and physiology

Sepiola rondeletii is separate sex. The females are larger than the males: They can reach a coat length of up to 60 mm, whereby the cut is 40 to 50 mm. The males, however, as far as is known, can only reach a maximum coat length of 25 mm.

The body as a whole is brown in color on the surface, short and with a rounded end. The trunk of the dwarf squid family is consistently only about half as long as the entire squid minus its arms.

poor

Four pairs of arms and a pair of tentacles grow out of the head, whereby the tentacles are club-like thickened at the tip and can be retracted into skin pockets below the eyes.

The arms are covered with suction cups from the base to the tip, with the tentacles it is only the tips of the clubs. The suction cups are arranged in two rows on all arms and eight rows on the tentacle lobes, with the latter partially shifting the rows into one another. As with all ten-armed cephalopods, the suction cups of Sepiola rondeletii are petiolate and reinforced with a keratochin ring.

In the male's upper left arm, the suction cups are enlarged at the end and partly fused to form a fleshy cushion, so that a mating arm ( Hectocotylus ) has arisen, which brings the sperm into the female during mating.

Coat, fins and shell

The head merges seamlessly into the trunk and is dorsally connected to the edge of the coat, so that a neck band is formed. The body is completely covered by the coat, with the wavy, lower edge of the coat clearly protruding from the body.

The short, paired fins are wide, rounded and only limited to the middle part of the body of the animal, so that there is no longer a continuous fin border. Their appearance is very reminiscent of wings.

As with most representatives of the cephalopods, the shell is only present internally. She is largely regressed and chitinous.

Eyes and other sense organs

On the head of these animals there are disproportionately large lens eyes, which have a similar structure to the lens eyes of vertebrates. The retina of the eyes is a brown-black colored, single-layer neuroepithelium , which essentially consists of two types of cells . The rods in the retina are bundled in what are known as rhabdomes, with the two halves of a rod belonging to different, neighboring rhabdomas.

Sepiola rondeletii also has an olfactory pit below the eyes and a number of light- sensing cells distributed over the entire body surface. Mechanical and chemical sensory cells still frequently occur in the skin of the mouth and on the suction cups.

Respiratory system

Sepiola rondeletii has two feather-shaped, inwardly directed gills, which can be found on the front wall of the mantle space. As with all squids, breathing takes place by alternately contracting and relaxing the muscles in the mantle, whereby water flows into the body through the gaps in the mantle and out through the funnel, flowing past the gills.

Chromatophores and staining

Sepiola rondeletii has the ability, typical of cephalopods, to camouflage itself in its environment through different colors. The animals are also able to adapt their body color to their emotional state: For example, they should turn pale when they are afraid and turn dark when they are angry. They can change their body color with the help of chromatophores and iridocytes that are embedded in the skin. The cells are located particularly close to the lower front edge of the mantle and on the surface of the tentacle lobes.

Sepiola rondeletii has the largest chromatophores among the cephalopods that are still visible to the naked eye. In addition, unlike most other cephalopods, this species has only one type of chromatophores with a dark pigment . Depending on how the cell is contracted, the color changes: If the cell is strongly contracted, it appears black; when it is relaxed, the volume of the cell is larger and it appears red-brown in color. The chromatophores only have one nucleus. This is larger than the surrounding tissue nuclei, but often difficult to see. The cell nucleus is surrounded by a simple cell membrane to which muscle fibers attach. These attach to the young, as yet unpigmented chromatophores and over time grow into vertically upright fibers. The muscle fibers are excited by the nervous system and contract, pulling the chromatophore membrane apart, causing the cell to gain volume and form a larger patch of color.

In Sepiola rondeletii, the iridocytes are large, smooth cells that reflect the incident light and, in combination with the chromatophores, give the skin a colored sheen. In the iridocytes, the iridosomes are usually distributed in a single layer and form stretched or meandering threads, some of which can also be glued together to form strands. Due to their different arrangement in the cell, there is an alternating reflection of the light.

If the chromatophores are stimulated, a "pulsation" occurs in which the cells expand rapidly in all directions, but contract again much more slowly. The pulsation rate is between 80 and 100 contractions per minute. As the animal dies, the pulses slow down until it develops into a permanent contraction.

Illuminating organs / mechanisms

Sepiola rondeletii lives in symbiosis with luminous bacteria that continuously emit light. These live in special pockets in the immediate vicinity of the three-lobed ink sack and can be shielded by it. In Sepiola rondeletii , both sexes have these pockets, whereby the animal does not have the bacteria from the start, but has to become infected with them after hatching. In the event of danger, the bacteria can also be ejected from the ink sack together with the ink, so that a glowing cloud of ink occurs in the water, which is supposed to distract the enemy from Sepiola rondeletii .

Genital organs

Both the males and the females have an unpaired gonad from which the mature sex cells fall into the mantle cavity.

In the case of the males, the mature sperm are closed in an approx. 1 cm long spermatophore , which is temporarily stored in the so-called spermatophore pocket, the enlarged end section of the outlet duct .

In females, in addition to the genital opening, large nidamental glands open into the mantle cavity, in which a secretion is produced to form the egg shell. In addition, the female has a large mating pouch inside the mantle cavity in which the male deposits his spermatophores.

physiology

Compared to other invertebrates, squids including Sepiola rondeletii have a highly developed nervous system.

The blood vessel system in Sepiola rondeletii is almost completely closed, as in all squids, there are only lacunae around the brain and the midgut gland. The hemolymph is pumped by the tubular, muscular heart through the body to the two gill hearts and the two gills. From there, the hemolymph, saturated with oxygen, returns to the two atria of the heart. The oxygen carrier in the hemolymph is hemocyanin .

During excretion, the products of excretion from the hemolymph migrate via the pericardium into the paired kidneys. These lead to the mantle cavity and flow out of the body next to the anus.

Food intake and digestion do not differ significantly between the individual cephalopod species and is best seen in Loligo sp. examined: The food enters the stomach through the mouth opening in the middle of the arm bases and is crushed by the movement of the stomach muscles. The nutrients are v. a. It is absorbed through the intestines and the indigestible components of the food are excreted through the anus.

Way of life

The exact population size of this species is unknown. It has been proven that the individual individuals of the species have a lifespan of 18 months and usually die shortly after reproduction. The species is also described as being rather sluggish compared to other cephalopod species.

Dig in

The animals living on the ground are predominantly nocturnal and usually spend the day buried in the sand to protect themselves from predators. It could be shown in the experiment that they leave their hiding place during the day when they are very starved. The digging process has already been examined in detail by Boletzky and Boletzky (1970), where they found contradicting the general opinion that Sepiola rondeletii digs itself in when the fins strike . They were able to divide the digging process into different phases: First, the animal sits down on the ground with its arms folded back. In the first phase, it whirls up the sand with targeted water jets from the funnel, so that a pit is formed under it. This pit provides support for Sepiola rondeletii when the animal pushes water backwards from the funnel. After enough sand has been blown away, the animal can sink into the pit with its fins attached. Then it pushes forwards so that the arms and head can sink in and a push backwards so that the coat bag can dip deeper. This is repeated until the animal is completely buried. In the second phase, the animal uses its arms to push sand over its body from the front, moving them synchronously. This process is also repeated several times.

Only when the substrate is unfavorable can the funnel thrusts be supported by the arms with shovel movements. If the animal has not been able to dig a pit to hold against the funnel thrusts, the recoil is compensated with opposite fin movements. According to the authors, this led to the erroneous assumption that the fins would be used for burying.

Locomotion

Even when swimming, Sepiola rondeletii usually stays close to the ground. The swimming is reminiscent of a bird's flight, as the fins are flipped up and down. This is supported by the recoil that occurs when the respiratory water is pressed out of the funnel.

Eating behavior

On the basis of observations in the aquarium it could be shown that Sepiola rondeletii does not lie in wait for prey like other dwarf squid buried in the sand. The animals dig up at dusk and then go looking for food at night. If they have found a prey, they quickly expel their tentacle arms (see arms) by contracting the circular muscles of the arms. Once they have caught prey, it is almost impossible for them to escape the grip of the tentacle suction cups, as a negative pressure has formed in the suction cups due to the withdrawn muscle plug.

Their prey includes v. a. small fish and crustaceans . But shrimp, krill and mussels are also sometimes on the menu.

Reproduction and development

Sepiola rondeletii is separate sex. The females are sexually mature from a coat length of 30 mm.

pairing

During the mating season, which runs from March to November, the male engages in a courtship ritual to present himself to potential females. If it succeeds, it swims under the female from behind so that their bodies point in the same direction. In addition, it wraps around the neck of the female and sucks on the female's belly with its second pair of upper arms to fix their position. With the hectocotylus (see arms) a spermatophore is then placed in the mating pouch of the female. The spermatophore gets through the mating pouch into the mantle cavity and bursts there, causing the egg cells to be fertilized in the mantle cavity. The eggs are laid directly after mating.

Egg and juvenile development

All octopuses lay eggs with a high yolk content, in which the embryo of Sepiola rondeletii grows rapidly. After hatching, the young animals get into the plankton and spend some time there until they transform into adults and change to a way of life on the sea floor.

Usage and threat status

Is caught Sepiola rondeletii rarely. This is most likely to happen when fishing with bottom trawls , sometimes also when fishing with purse seine . The highest probability is as bycatch by shrimp fishermen.

Sepiola rondeletii is rarely found in fish markets, although its meat is very tasty. Most of the time, the animal is consumed immediately after being caught, as it is very difficult to preserve.

Since this species is rarely caught and not fished commercially, it is not threatened and there are no protective measures so far. However, it must be said that the population data have not yet been adequately researched.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d R. Riedl: Fauna and flora of the Mediterranean . Publisher Paul Parey, Hamburg / Berlin 1983.

- ^ Serge Gofas, Bastien Tran, Philippe Bouchet, Julian Finn: Sepiola rondeletii Leach, 1817. In: World Register of Marine Species. TN Bezerra, CB Boyko, D. Domning, et al., June 2, 2016, accessed November 2, 2019 .

- ↑ a b E. Wilson: Dwarf bobtail. Sepiola rondeletii. In: Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Reviews. H. Tyler-Walters, K. Hiscook, November 6, 2011, accessed November 2, 2019 .

- ↑ a b A. Naef: Teuthological notes . In: Zoologischer Anzeiger . No. 39 , 1912, pp. 241-248, 262-271 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l L. Allcock, I. Barratt: Sepiola rondeleti, Dwarf Bobtail Squid . In: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species . 2012.

- ↑ a b c d e f g A. Reid, P. Jereb: Familiy Sepiolidae . In: P. Jereb, CFE Roper (Ed.): Cephalopods of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalog of species known to date. FAO, Rome 2005, p. 153-203 .

- ↑ a b c d Sepiola rondeletii Leach, 1817 dwarf bobtail squid. In: SeaLifeBase. MLD Palomares, D. Pauly, March 30, 2009, accessed November 1, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e A. L. Allcock, PJ Hayward, GD Wigham, et al .: Molluscs (Phylum Mollusca) . In: PJ Hayward, JS Ryland (Eds.): Handbook of the Marine Fauna of the North-West Europe . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2017, pp. 455-602 .

- ↑ a b c d e R. Kilias: Tribe Mollusca . In: new large animal encyclopedia - the Urania animal kingdom in 6 volumes . tape 1 : Invertebrates 1. Fackelverlag, Stuttgart 1975, p. 318-507 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p H. E. Gruner, G. Hartmann-Schröder, R. Kilias: Invertebrates: Mollusca, Sipunculida, Echiurida, Annelida, Onychophora, Tardigrada, Pentastomida . In: Textbook of special zoology . tape 1 , part 3. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena 1993.

- ↑ a b W. Westheide, G. Rieger (Ed.): Special Zoology . Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 2013.

- ↑ R. Hesse: Investigations into the organs of the sensation of light in lower animals: the eyes of some mollusks . In: Journal of Scientific Zoology . No. 68 , 1900, pp. 379-477 .

- ↑ a b c d e H. Winterstein: Handbook of comparative physiology . Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena 1914.

- ^ JAC Nicol: The biology of marine animals . Interscience Publishers, New York 1960.

- ↑ a b S. von Boletzky, M. von Boletzky, D. Frösch, et al .: Laboratory rearing of Sepiolinae (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) . In: Marine Biology . No. 8 , 1971, p. 82-87 .

- ↑ a b S. Boletzky, M. von Boletzky: The digging in sand with Sepiola and Sepietta (Mollusca, Cephalopoda) . In: Revue suisse de zoologie . No. 77 , 1970, pp. 536-548 .

- ^ S. Jaeckel: Mollusks . In: the animal kingdom . tape 5 . Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin 1954.

- ^ GA Boulenger, CL Boulenger: Animal life by the sea-shore . "Country life", Ltd., London 1914.

literature

- AL Allcock, PJ Hayward, GD Wigham, et al .: Molluscs (Phylum Mollusca) . In: PJ Hayward, JS Ryland (Eds.): Handbook of the Marine Fauna of North-West Europe. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2017, pp. 455-602 .

- A. Naef: Teuthological notes . In: Zoologischer Anzeiger . No. 39 , 1912, pp. 241-248, 262-271 .

- A. Reid, P. Jereb: Family Sepiolidae. In: P. Jereb, CFE Roper (Ed.): Cephalopods of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalog of species known to date. FAO, Rome 2005, p. 153-203 .

- GA Boulenger, CL Boulenger: Animal life by the sea-shore. "Country life", Ltd., London 1914.

- HE Gruner, G. Hartmann-Schröder, R. Kilias: Invertebrates: Mollusca, Sipunculida, Echiurida, Annelida, Onychophora, Tardigrada, Pentastomida. In: Textbook of special zoology. tape 1 , no. 3 . Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena 1993.

- H. Winterstein: Handbook of comparative physiology . Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena 1914.

- JAC Nicol: The biology of marine animals. Interscience Publishers, New York 1960.

- L. Allcock, I. Barratt: Sepiola rondeleti, Dwarf Bobtail Squid . In: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012 . 2012.

- R. Hesse: Investigations into the organs of the sensation of light in lower animals. Part 6: the eyes of some mollusks. In: Journal of Scientific Zoology. No. 68 , 1900, pp. 379-477 .

- R. Kilias: Tribe: Mollusca . In: new large animal encyclopedia - the Urania animal kingdom in 6 volumes. 1: Invertebrates 1. Fackelverlag, Stuttgart 1975, p. 318-507 .

- R. Riedl: Fauna and flora of the Mediterranean . Publisher Paul Parey, Hamburg / Berlin 1983.

- S. Boletzky, M. von Boletzky: Digging into sand with Sepiola and Sepietta (Mollusca, Cephalopoda) . In: Revue suisse de zoologie . No. 77 , 1970, pp. 536-548 .

- S. von Boletzky, M. von Boletzky, D. Frösch, et al .: Laboratory rearing of Sepiolinae (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) . In: Marine Biology . No. 8 , 1971, p. 82-87 .

- S. Jaeckel: Mollusks . In: The animal kingdom . tape 5 . Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin 1954.

- W. Westheide, G. Rieger (Ed.): Special zoology . Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 2013.