Qumran scriptorium

The exposed remains of a building ( Locus 30) of the Khirbet Qumran archaeological site on the Dead Sea are known as the scriptorium of Qumran . The term was coined by the excavator Roland de Vaux and thus aroused possibly misleading associations with scriptoria within Christian monasteries . The earlier meaning of the excavated building is still controversial today. Along with the rest of the settlement, the so-called scriptorium was also destroyed by the Roman Legio X Fretensis in 68 AD .

Chronology of the excavation

The archaeological dig in Khirbet Qumran, to which the scriptorium of Qumran belongs, has always been overshadowed by the exploration of the rock caves in the vicinity, in which the Dead Sea Scrolls were found between 1947 and 1956 . Khirbet Qumran was investigated in five campaigns under the direction of Roland de Vaux:

- November 24 to December 1951: start of archaeological work

- February 9 to April 4, 1953: Second campaign

- February 15 to April 15, 1954: Third campaign

- February 2 to April 6, 1955: Fourth campaign

- February 18 to March 28, 1956: Fifth Campaign

The building

The building in which the scriptorium of Qumran was located was originally two-story and had a floor area of about 13 × 4 meters. Only the walls on the ground floor have been preserved. Its location on the central courtyard, the size and the good construction indicate that this building played an important role in the Qumran settlement. The upper floor was reached via two flights of stairs, one of which was from Hasmonean times and the other from Herodian times. When the upper floor collapsed, the ground floor was filled with rubble.

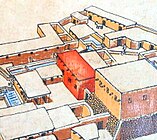

- Scriptorium of Qumran (Locus 30)

The plaster furniture from the upper floor

Roland de Vaux used the term "plastered elements" to describe long, narrow objects from the upper floor in his excavation diaries, which could be assembled from fragments of mud brick plastered with plaster in the rubble. The largest specimen (KhQ 967) is about five meters long and 50 centimeters high, the front is arched, the back is straight, but only roughly worked. The top is 40 cm wide, but the base of this strange piece of furniture is only 18 cm. That means that no one could sit or lie on this table-like plaster of paris furniture without it collapsing.

An equally long, bank-like element (KhQ 968) is very low and narrow. Fragments of two further table-like plaster of paris furniture and a bench-like structure were found (KhQ 969–971).

The finds from the upper floor also include a kind of rimmed plaster tray with two round recesses (KhQ 966). Other small finds from Locus 30 were: a bronze needle, an iron key, a limestone seal, a few coins and small quantities of household utensils.

The inkwells from Locus 30

A clay and a bronze inkwell (KhQ 463 and 473) were found under the rubble of the upper floor, and a third inkwell, also made of clay, was recovered in the neighboring room (Locus 31).

Yizhar Hirschfeld argued: Taken alone, the ink pots would have been assigned to the hall on the ground floor, not the upper floor; In addition, inkwells are no longer unique among found objects - unlike what de Vaux's team had to think. In the roughly contemporary house of the Qathros family in Jerusalem, for example, two inkwells were also found. Since he interpreted the Qumran settlement as an estate, Hirschfeld suspected that the management of the estate, which included paperwork, was located on the ground floor of Locus 30.

With the majority of researchers, Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra considers the find of several inkwells to be rare and significant: “The local preparation of the ink of the hymn scroll (1QH a ) proves ... that some of the scrolls found in cave 1 were written in Qumran is. We can also conclude from the inkwells that writing activities took place in Qumran. It remains to be seen whether this happened to the installations in L [ocus] 30. "

Excursus: Examining the ink of 1QH a

A team led by Ira Rabin and Oliver Hahn ( Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing , Berlin) took a remarkable approach . One made use of the fact that the soot ink common in Qumran was only mixed with water shortly before use. The team subjected the hymn scroll to an X-ray fluorescence analysis and found bromine- to- chlorine concentrations in the ink that are characteristic of the waters of the Dead Sea . This practically proves that this scroll was written in Qumran.

Inkwells and writing implements associated with Qumran

In 1997, the Jordan Archaeological Museum in Amman presented the two inkwells that de Vaux had found in Locus 30 in an exhibition.

Two ceramic inkwells "from the scriptorium" are now in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem . They look very similar to each other, have a cylindrical shape, are 6 cm high and 4.5 cm in diameter. The same museum has two other Qumran inkwells, one of which is clay, 6.4 cm high and 3.1 cm in diameter. So it's a bit narrower than the other two and has a restored handle. The other inkwell is turned from wood and 6 cm high.

A total of nine inkwells are known to date. One of them comes from Ain-Feshkha ; for three it is unclear whether they were even found on the Qumran site. Like many Qumran fragments, these three ended up in the antique trade through the Bethlehem intermediary "Kando". John Marco Allegro acquired a copy in 1953 and it ended up in the Schøyen Collection (MS 1655/2) via private collectors : an 8 cm high bronze vessel in the shape of a basket with two handles, with remains of ink inside. Ira Rabin studied this substance in 2016. It was black carbon-based ink with a proteinaceous binder. Such an ink has not yet been detected in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Kando's statement that it was a surface find from Qumran is probably incorrect. Another ceramic inkwell allegedly from Qumran that Kando brought to market was donated to the University of Southern California .

Kando is also said to have brought two copies of the Qumran stylus (MS 5095/3) onto the market. They are the only writing implements that have so far been claimed to be related to Qumran. They are three inches long, made from the rib of a palm leaf, and have ink buildup. They are said to come from cave 11. They were acquired from a Swiss private collection and are now in the Schøyen Collection.

Interpretations of the upper floor

Scriptorium

Roland de Vaux interpreted the plaster furniture on the upper floor as furnishing a writing room and assumed that the Dead Sea scrolls found in the nearby caves were written here. This interpretation has a problem: ancient scribes wrote cross- legged on their knees. Crouching cross-legged on the low bench and writing on a sheet of paper lying on the table, the ancient scribe would have assumed a very impractical position for him. That being said, writing at tables is only attested centuries later and is anachronistic for Qumran.

The individual sheets of parchment were lined, written on and only then sewn together to form a roll in a final step. The leaf size of the Dead Sea Scrolls varies between 21 and 90 cm.

The alternative proposed by Bruce Metzger , that the clerks would have sat on the “table” and the “bench” would have served them as a kind of footstool, fails because of the instability of the large plaster of paris furniture.

Kenneth Clark had the Qumran clerks sit cross-legged on the low “bench” and identified the “table” as a place to put their material.

Side room of the library

For Hartmut Stegemann , too , Qumran was a center of scroll production, but he saw no writing workshop on the upper floor of Locus 30. He hypothesized that the long plaster tables were used to open the precious scrolls and look for passages in them without damaging the scrolls. Only then were they given to copyists or readers. Upon return, a settlement librarian rolled the parchment back up on the table before placing it on the shelf.

Dining room

The interpretation as a classic triclinium (Pauline Donceel-Voute) fails because the “benches” are much too narrow as couches, as Ronny Reich has shown. But several people could have sat cross-legged on the "benches" and eaten at the tables. There were comparable dining rooms “in underground Cappadocian cities. However, these are from a much later time and from a completely different region. "

literature

- Roland de Vaux: Archeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls: The Schweich Lectures of the British Academy 1959 . Rev. ed. London, 1973.

- Bruce M. Metzger: The Furniture in the Scriptorium at Qumran . In: Revue de Qumran 1 (1958/59), pp. 509-515.

- Kenneth W. Clark: The Posture of the Ancient Scribe . In: Biblical Archaeologist 26 (1963), pp. 63-72.

- Ronny Reich: A Note on the Function of Room 30 (the 'Scriptorium') at Khirbet Qumrân . In: Journal of Jewish Studies 46 (1995), pp. 157-160.

- Hartmut Stegemann: The Essenes, Qumran, John the Baptist and Jesus . Herder, 10th edition, Freiburg im Breisgau 2007

- Yizhar Hirschfeld: Qumran - the whole truth. The finds of archeology - reassessed . (Original title: Qumran in Context. Reassessing the Archaeological Evidence .) Gütersloh 2006, pp. 139–143.

- Emanuel Tov : The Copying of a Biblical Scroll ( online with its own page count). In: Hebrew Bible, Greek Bible, and Qumran. Collected Essays, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2008.

- Ira Rabin, Oliver Hahn, Timo Wolff, Admir Masic, Gisela Weinberg: On the Origin of the Ink of the Thanksgiving Scroll (1QHodayot a ) . In: Dead Sea Discoveries 16/1 (2009), pp. 97-106. (Abstract online )

- Ira Rabin: Ink Sample from Inkwell MS 1655/2. In: Torleif Elgvin , Michael Langlois, Kipp Davis: Gleanings from the Caves: Dead Sea Scrolls and Artefacts from the Schøyen Collection , Bloomsbury, London 2016, pp. 463–464.

- Kaare Lund Rasmussen, Anna Lluveras Tenorio, Ilaria Bonaduce, Maria Perla Colombini, Leila Birolo, Eugenio Galano, Angela Amoresano, Greg Doudna, Andrew D. Bond, Vincenzo Palleschi, Giulia Lorenzetti, Stefano Legnaioli, Johannes van der Plicht, Jan Gunneweg: The constituents of the ink from a Qumran inkwell: new prospects for provenancing the ink on the Dead Sea Scrolls . In: Journal of Archaeological Science 39 (2012), pp. 2956-2968. ( online )

- Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra: Qumran: The Dead Sea Texts and Ancient Judaism (UTB 4681). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2016, ISBN 9783825246815 , pp. 112-114.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Martin Peilstöcker: Qumran: A Chronology of Events . In: World and Environment of the Bible . No. 87 , January 2018, p. 10-13 .

- ↑ Yizhar Hirschfeld: Qumran . S. 139 .

- ↑ Othmar Keel, Max Küchler: Places and landscapes of the Bible. A handbook and study guide to the Holy Land . tape 2 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1982, p. 469 .

- ↑ a b Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra: Qumran . S. 114 .

- ^ Catherine M. Murphy: Wealth in the Dead Sea Scrolls and in the Qumran Community . Brill, 2001, p. 300 .

- ↑ a b c Yizhar Hirschfeld: Qumran . S. 142 .

- ^ Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra: Qumran . S. 141-142 .

- ^ Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra: Qumran . S. 60 (Publication of the results of the ink analysis: 2009, see literature.).

- ↑ Emanuel Tov: The Copying of a Biblical Scroll . S. 13 .

- ↑ Inkwells from the scriptorium. Retrieved February 11, 2018 .

- ↑ Explore the Collection: Inkwell. Retrieved February 11, 2018 .

- ↑ Explore the Collection: Inkwell. Retrieved February 11, 2018 .

- ^ Qumran Inkwell. Retrieved February 11, 2018 .

- ↑ Ira Rabin: Ink Sample from Inkwell MS 1655/2 . S. 464 .

- ↑ Daniel Stölk Ben Ezra: Qumran . S. 35 .

- ^ The Only Surviving Qumran Stylus. Retrieved February 11, 2018 .

- ↑ Emanuel Tov: The Copying of a Biblical Scroll . S. 14 .

- ↑ Emanuel Tov: The Copying of a Biblical Scroll . S. 5 .

Coordinates: 31 ° 44 ′ 30 " N , 35 ° 27 ′ 33" E