TPLO

TPLO (Abbreviation for Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy ) is a surgical procedure in animal surgery that has been used to treat torn cruciate ligaments in dogs since 1998 . The method was developed in the 1990s by the American scientists Barkley and Theresa Devine Slocum. With the TPLO, the tibia (shinbone) is cut through a round cut and screwed again in a different position using specially designed, patented plates. The aim is to use the modified biomechanics to avoid the forward movement that is normally intercepted by the anterior cruciate ligament.

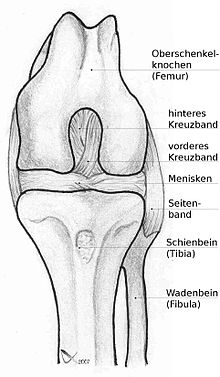

Bone structure of the hind limbs

The knee joint connects the upper and lower legs . The knee joint, and not the ankle , as is often wrongly assumed , is the most important joint for the dog's locomotion. The angle of the knee joint is decisive for the thrust of the hindquarters. This results in angles of 130 ° for working dogs and up to 159 ° for greyhounds. Dog breeds at a particularly steep incline have a tendency to jump out of the kneecap ( patellar luxation ). The knee joint is so important because, in cooperation with the hip joint and the ankle joint, it initiates the movement of the leg and thus the entire animal. It must therefore be made particularly strong and should be angled as deeply as possible. It is from this joint that the strongest impacts are transmitted to the whole body. On the one hand, the kneecap and on the other hand the ligaments, which also include the cruciate ligaments , ensure that the direction is maintained. It also prevents excessive extension of the limb. The lower leg, which adjoins the knee joint is formed of two bones: the shinbone (tibia) and the fibula (fibula). The latter lies behind the shin, rotated by 90 °. The shin bones the body weight.

If, in the normal position of the dog, a perpendicular is dropped from the hip joint, it represents the dog's line of gravity, which crosses the lower leg once. The knee joint is therefore in front of the median line and the ankle joint behind it.

Tear of the anterior cruciate ligament in the dog and its consequences

The cruciate ligaments in the dog's knee have an important stability function. It should be noted here that because of the angulation in the hind leg, this function is even more important than it is in humans, who have most of the important joints in the median line . Both cruciate ligaments are strongly developed in the dog.

In contrast to humans , the anterior cruciate ligament in dogs often ruptures without prior trauma (such as an accident). In most cases, the ligament is chronically improperly stressed, which can have various reasons. According to current knowledge, a major cause is too steep an angle of the articular surface of the lower leg - the “tibial plateau”. With every step, too much forward thrust ( cranial tibial thrust ) is placed on the cruciate ligaments. The steeper the joint surface, the greater this forward thrust. This situation can be compared with an inclined plane , whereby the object that is pulled down by gravity is protected from sliding down by a band (comparable to the function of the cruciate ligament). Small tears appear in the cruciate ligament, which increase until a slight wrong movement is enough to tear the ligament. In this context, one speaks of a minor trauma. Typical scenarios are excited ball games, playing with other animals, hunting on uneven terrain or slipping on smooth surfaces. Almost all races and all age groups are affected by such a torn ligament . However, larger breeds are more prone to rupture because the weight increases the forward thrust.

Since the supportive effect of the ligament is lost in the event of a cruciate ligament tear, instability in the knee occurs, which has far-reaching consequences. Due to the lack of guidance, the knee joint is now exposed to strong friction, which causes pain and leads to irreparable arthritis in the joint and cartilage damage. Another consequence of the damage to the joint is that the misalignment and stress can lead to a change in the entire spine and, in addition, the structure of the bones and muscles can change.

Symptoms

After such a minor trauma has occurred, the animals are usually moderately lame . This means that the gait pattern is disturbed and the dogs no longer use the affected limb continuously. The dogs often “run in” again, which ultimately leads to the dog owner not attaching too much importance to the problem and assuming a strain . As the problem persists, the animals have great difficulty getting up and limp afterwards.

While a complete cruciate ligament tear can be diagnosed relatively easily and without any special effort, it is often very difficult to make a correct diagnosis if the ligament is torn. One method that the treating veterinarian often uses is the so-called drawer test . With him, the thigh and lower leg are shifted against each other. This makes it easy to determine the instability in the joint.

In the further course of the disease, the meniscus is heavily stressed, which leads to a tear or its overturning. If you listen carefully, you can hear the meniscus flipping over. This phenomenon is called the meniscus click .

Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy - TPLO

In the past, veterinarians who wanted to carry out a TPLO were trained by Slocum himself in some advanced training courses. Also due to the high cost of diagnostics or arthroscopy and the operation itself, a relatively high price compared to conventional methods is justified. This moves on average around 1700–2000 euros, not including aftercare.

The idea of the TPLO

To date, around 50 different methods have been developed to treat an anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Most surgical techniques are derived from human anatomy and achieve poor results, with the prognoses for small and light animals being relatively good. Dogs heavier than 30 kg have a poorer chance of success. The main reason for this is that small dogs have much less force on the joint. Even with sport and service dogs, the success of "old" surgical techniques is not to be expected very much.

Because of the more or less bad successes, the American scientists Barkley and Theresa Devine Slocum developed a method that differs significantly from all previous methods: the TPLO ( Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy ). The idea behind this is to stop the forward movement that acts on the knee joint by changing the position of the joint surface of the lower leg so that it cancels out all forces. The repair of the anterior cruciate ligament and thus the opening of the knee joint should largely be avoided. However, if the meniscus is already severely damaged, the knee must still be opened and the destroyed remains of the affected part of the meniscus removed. According to the latest findings, however, attempts are being made by means of an arthroscopy to check whether it is absolutely necessary to open the knee.

Since the angular position is responsible for the advance, the existing angle of the tibial plateau is determined and theoretically optimized in a complicated process. For this purpose, various x-rays are taken and the required angle is determined. However, patients who are operated on with a conventional method must expect the arthritic changes to progress. With TPLO, on the other hand, the knee either remains completely free of osteoarthritis or only 1st degree osteoarthritis develops (at a maximum of 3 degrees).

The surgical technique of the TPLO

The tibia of the affected limb is cut using a patented circular saw. At the interface, the upper part of the tibia is rotated in such a way that the previously calculated biomechanically optimal angle is achieved. Once this has been reached, the separated bone is screwed back on with a six-hole plate specially designed for this purpose. The procedure is basically adapted to the treatment of a broken bone . An important aspect here, however, is that the fibula is undamaged, because a large part of the support load now rests on the fibula during the healing phase of the tibia. If the fibula is damaged, it is imperative to treat it beforehand.

Post-operative care

Patients who have had surgery after a TPLO must be kept quiet for up to 12 weeks to ensure good bone healing. However, the operated dogs are usually back on their feet relatively quickly and use the operated leg well. A lead of around four weeks compared to conventional methods can usually be expected.

Painkillers and antibiotics are given immediately after the operation . The animals should move and, if possible, put good weight on the leg after 2 weeks so that a muscle can slowly build up again. Basically, one can speak of two phases during the healing process: a healing phase that lasts 6–12 weeks and during which the changed biomechanics and arthritic processes in the knee are supposed to heal; and a rehabilitation phase in which the patient must learn to use the leg actively again so that the muscles in the leg are strengthened again.

Accompanying measures

The following must be observed throughout the healing phase:

- The dog must not become overweight, otherwise the strain on the operated knee would become too great.

- The dog must always be kept on a leash, especially at the beginning.

- Romping around, lawning around the garden fence, playing in deep snow, mountain tours, jumping or playing with other dogs is strictly prohibited and must be avoided.

It is also advisable to see an animal physiotherapist . He can then take supportive measures specially tailored to the needs of the dog, which usually leads to accelerated healing. Such measures are massages , electricity therapy , exercise training with equipment or the underwater treadmill . After about eight weeks, the patient should slowly increase the load, whereby the emphasis here must be on "slow".

Long-term successes of the TPLO

Detailed studies on the long-term results of the TPLO are not available. In a study with 101 dogs, the TPLO-operated group showed no more lameness in over 50% of the dogs, the rest only a minor group, in contrast to the group treated according to other surgical methods. The animals' pain was also reduced on average.

Dangers and problems

The TPLO is a massive intervention in the biomechanics , which can easily lead to complications. In 2006, a long-term study of TPLO patients was published in which around 700 animals were observed over a period of 30 months. The complication rate here was 18.8 percent. The problems recorded in the study were for example:

- increased tendency to bleed (haemorrhages)

- Swelling where the first incision was made

- premature removal of the threads by the patient himself, for example by licking the wound. It is essential to ensure that this is not done, as otherwise the mechanical action of the tongue on the wound can cause germs to enter the wound and a severe infection can result.

- Fracture of the tibia bulge ( tibial tuberosity )

- Swelling of the patella ligament: Long-term studies show that inflammation (desmitis) and swelling of the patella ligament occur after a TPLO. The extent to which this leads to restricted mobility or lameness has not yet been clarified.

- Problems with the implant

Experience reports have shown that temporary numbness in the operated limb (from the bandage or the operation itself) can occur again and again. This is then expressed in the paw " killing over ". This means that the dog walks on the back of its paw and is apparently unable to control the paw properly in order to correct its gait.

Another problem, which is mainly cited by veterinarians who prefer the newer TTA (Tibial Tuberosity Advancement), but for the accuracy of which hardly any materials are available, is the risk of irreparable damage to important vessels and nerves during the operation, which can eventually lead to total limb loss.

References and literature

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Aldington, Eric HW: From the body of the dog. Physique, forms of movement, growth, diseases, HD, breed characteristics. 3. Edition. Verlag Grollwitzer, Weiden 1993, ISBN 3-923555-04-0

- ↑ a b c Helmut Steger et al .: Information for our customers on the subject of cruciate ligament rupture - postoperative care. Available at: http://www.tierarzt-piding.de/Merkblatt.pdf [as of October 4, 2007]

- ↑ a b c d e Hubert Röpcke et al .: Cruciate ligament tear in dogs ( Memento from February 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Helmut Steger et al .: Cruciate ligament tear - TPLO. Available at: http://www.tierarzt-piding.de/01_ORTHO03.htm [as of October 4, 2007]

- ^ Daniel Damur: Cruciate ligament tear in dogs. Available at: http://www.kleintiermedizin.ch/hund/kreuzband/kreuzband3.htm [as of October 4, 2007]

- ↑ a b H.-P. Early: The cruciate ligament tear in the dog. Available at: http://www.animalcare.ch/betreuung/PRESS73.pdf ( Memento from October 19, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 16 kB) [Status: October 4, 2007]

- ^ Slocum Enterprises Inc .: Frequently Asked Questions ( Memento from September 15, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) [Status: October 4, 2007]

- ↑ Phillip Kloene: Therapy results in dogs with a (partial) rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament after arthroscopy and minimally invasive lateral thread restraint as well as after Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO). Dissertation, 2005. Available at: http://elib.tiho-hannover.de/dissertations/kloenep_ws05.pdf [as of October 5, 2007]

- ↑ Kent D. Stauffer et al .: Complications Associated With 696 Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomies. In: Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association

- ^ KL Mattern et al .: Radiographic and ultrasonographic evaluation of the patellar ligament following tibial plateau leveling osteotomy. In: Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 47 (2006), pp. 185-191.

- ↑ Meinhard Maurer: Tibial Tuberosity Advancement for the Treatment of Torn Cruciate Ligament. ( Memento from August 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) [Status: October 5, 2007]

further reading

- Eric HW Aldington: From the Health of the Dog. From skin and hair problems, allergies, youth and old age, medication, medicinal herbs, home remedies. 2nd Edition. Verlag Grollwitzer, Weiden 1996, ISBN 3-923555-09-1

- Klaus-Dieter Budras, Wolfgang Fricke: Atlas of the anatomy of the dog. Compendium for veterinarians and students. Schlütersche Verlagsanstalt, Hanover 1983, ISBN 3-87706-081-1

- Kay Schmerbach: Investigations into the position of the dog's hind limbs with regard to the rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament with special consideration of the tibial plateau. Leipzig 2006, pdf