Surveying and naming Mount Everest

The surveying and naming of Mount Everest was a sequence of events that dragged on over several years from 1845 to 1858.

prehistory

The Himalaya was the Europeans virtually unknown, as long Nepal and Tibet were closed to Europeans. From India snow-capped peaks could be seen in a great distance, but their position and height could not be made out and which always looked different depending on the viewer's point of view. If you got closer, they quickly disappeared behind other mountains (for example, from Kathmandu only the Lhotse can be seen, but does not seem to tower above any of the surrounding mountains). The local population and the traders and pilgrims who crossed the Himalayas on a few paths at heights of well over 5000 m knew the mountains by sight, but were not interested in their exact location. There was no exact description of the location and no map showing the mountains. Until the 19th century, the map drawn up by Jean-Baptiste Régis in 1717 and revised by Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville in 1835, which was based on the information of two lamas sent to Tibet, was the best map - but it only showed rows of schematized small sheets instead of individual mountains. Even the exact location of Lhasa was unknown.

The Great Trigonometric Survey of India , which William Lambton had begun in 1802 on behalf of the British East India Company in the south of the subcontinent, had arrived in Dehradun at the foot of the Himalayas in 1834 under his successor George Everest . Everest, however, focused on completing the measurement of the great meridian arc from the southern tip of India to Dehradun. After its completion, he retired and returned to England in 1843. He has therefore never seen the mountains in eastern Nepal that are more than 900 km away.

Surveying the Himalayan peaks, discovery of Peak XV

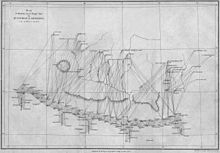

Everest's successor, Andrew Scott Waugh , undertook survey work from Dehradun east along the Himalayas to the region south of Darjeeling . Since the Nepalese government did not grant access to their territory, the work on the longest of the numerous triangulation series between 1845 and 1850 had to be carried out with great losses through the malaria-infested jungle and swamp areas of the Terai at the foot of the Himalaya. 40 Indian employees died in a single season. Almost half of British surveyors contracted jungle fever and died on site or in the following years.

The various survey teams also took bearings on the white peaks that were sometimes visible in the distance. With these one-sided bearings it was of course not possible to determine the distance of the targeted summit or its height. The individual surveyors initially gave the targeted peaks in their records individual names such as peak b . Only when evaluating the data and reports was it possible to connect the bearings on plans to form triangles. While the triangulation series mostly measured triangles with edge lengths of around 30 to 50 km (19 to 31 miles ) and not more than 100 km (62 mi.), Triangles with edge lengths between 130 km and more than 220 km were now obtained. In this way, the position of 79 peaks could be drawn with some precision on an almost empty map sheet. Only 31 peaks were known by name, the others were now numbered with Roman numerals. Peak b became peak XV , which was sighted from seven different survey points that were spread over a distance of more than 220 km. While the Dhaulagiri , later the Kangchenjunga , had previously been regarded as the highest known mountain, the assumption now arose that Peak XV was even higher.

Radhanath Sikdar , who was hired by Everest in 1831 as a mathematical assistant and who has meanwhile risen to Chief Computor of the Survey of India , now made extensive and complex calculations in which sources of error such as light diffraction and temperature and air pressure fluctuations were taken into account as far as possible at that time - at one time when slide rules were not yet common. In 1852 he came to the conclusion that Peak XV at 29,002 feet was the highest of the targeted peaks and thus probably the highest mountain in the world. However, Andrew Waugh initially hesitated to publish this result, as it did not seem to him to be sufficiently certain due to the great distance. It was only after numerous checks and control calculations that he finally announced in a letter to the Royal Geographical Society dated March 1, 1856 that Peak XV was probably the highest mountain in the world and had a height of 29,002 feet (8840 m).

Naming of Mount Everest

With the measurements, the coordinates of the highest of all mountains were determined with some precision, but its specific surroundings, such as neighboring mountains, rivers, paths and the nearest villages, remained unknown.

George Everest made it a rule to name all geographic objects by their native names. His successor Andrew Waugh also followed this rule. He emphasized this in his letter to the Royal Society, but in the case of Peak XV it was not possible to determine with certainty from a great distance what the local population called it. That's why he named it Mont Everest in honor of his predecessor . The meeting of the Royal Geographical Society on May 11, 1857, in which Waugh's letter was read, was also presented with a letter from Brian Houghton Hodgson , the British envoy in Kathmandu , Nepal, that the local name was known, namely Déodúngha or Dévadúngha ( Holy Mountain ). The congregation, however, accepted Waugh's proposal. George Everest, who was present, was grateful for the honor, but indicated that his name could not be pronounced in India and that it could not be written in Hindi or Persian. However, the naming with Mount Everest remained .

Andrew Waugh challenged Hodgson's view that the local name was known in a later letter dated August 5, 1857, read at the meeting of the Royal Geographical Society on January 11, 1858. Hodgson only argues by hearsay that he himself has never seen the mountain. Hodgson only speaks of a mountain and does not take note of the fact that there are several mountains close together. The name given by Hodgson could therefore designate one of the measured mountains or one that has not yet been seen. That can only be clarified by a correct measurement on site. Incidentally, his employees had independently stated that due to the great distance it was not possible to determine the identity of Mount Everest with the Deodangha mentioned by Hodgson.

The letter was apparently not discussed further at the meeting. The President of the Royal Geographical Society concluded with words of appreciation for the naming of the highest mountain in the world with the name Everest.

It is an irony of history that the mountain is named after George Everest all over the world today, but in the wrong pronunciation because the Everest family pronounced "Eve-rest" ("Eve" for "evening" with a long "i") out.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b The Highest Mountain in the World, by John Keay From the book: Everest, Summit of Achievement . On the Royal Geographic Society website; Retrieved September 12, 2012

- ↑ La Chine la Tartarie Chinoise et le Thibet

- ^ A b c d Clements R. Markham: A Memoir on the Indian Surveys . (PDF; 60.6 MB) 2nd edition WH Allen & Co., London 1878. Digitized at archive.org

- ↑ Derek Waller: The Pundits . The University Press of Kentucky, Kentucky 1990, ISBN 0-8131-1666-X

- ↑ R. Ramachandran: Survey Saga on Frontline, April 27, 2002. Retrieved July 21, 2012

- ^ A b Andrew Waugh: Letter to the Royal Geographical Society of March 1, 1856 . In: Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London, no.IX , p. 345. Digitized on GoogleBooks

- ↑ Soutik Biswas: The man who 'discovered' Everest on BBC News online, accessed September 4, 2012

- ↑ A letter to the editor of the American Statistician (on JSTOR , accessed September 4, 2012) claims that the actual end result from the numerous calculations was the smooth amount of 29,000 feet. However, it was agreed that no one would accept this smooth amount as the exact result of extensive and tedious calculations and therefore arbitrarily added 2 feet (61 cm) in order to be able to announce a more credible exact amount.

- ↑ The value of 29,002 feet is the arithmetical mean of six different values listed in Waugh's letter to the Royal Geographical Society of March 1, 1856.

- ↑ In his letter of March 1, 1856, Waugh still uses the French form Mont , which he gave up in the next correspondence.

- ↑ Waugh's letter of August 5, 1857 on JSTOR; Retrieved September 4, 2012

- ↑ The comments are attached to Waugh's letter.

- ↑ A note signed by Andrew Waugh was attached to the minutes of the meeting, according to which the longitude given for Mount Everest refers to the old value for the observatory in Madras, which deviates from the two values, on the one hand by the Admiralty and the Royal Astronomical Society and on the other hand would be accepted by Taylor based on his observations from 1845. (Since Lambton, the measurements were based on the coordinates of the observatory in Madras. The problem of the correct longitude was known, but could only be solved later with newer technical methods.) The height information was based on the sea level in the mouth of the Hugli , which was used with the measurement the sea levels in Bombay and Karachi have been matched.

- ↑ Wade Davis, Into the Silence. London (Random House) 2011, ISBN 9780099563839 , p. 46.