Large trigonometric survey

The Great Trigonometric Survey (English Great Trigonometric Survey ) was the project for the basic surveying of the Indian subcontinent by means of trigonometric surveying networks , which extended over most of the 19th century. It was accompanied by the measurement of the meridian arc between Cape Comorin , the southern tip of India, and a small mountain at Mussoori in Uttarakhand in the foothills of the Himalayas , which became known as The Great Arc and one of the more than 2500 km (1500 miles) in length longest meridian arcs of the earth measurement at that time . The initiator and long-term leader of the project was William Lambton ; after his death it was continued by George Everest and Andrew Scott Waugh and finally completed by James Thomas Walker .

prehistory

In the 18th century the British East India Company had a number of more or less contiguous possessions in India, but the subcontinent was in principle still unknown to Europeans. First, especially the coasts were from the ships of the East India Company from using compass - bearings and astronomical local regulations a necessarily inaccurate method - measured. James Rennell , Surveyor-General of Bengal from 1767 to 1777 , had surveyed large parts of Bengal and mapped the provinces along the Ganges until shortly before Delhi and published it in the Bengal Atlas in 1779 , which was followed by the first geographically accurate map of India in 1783. A number of other surveys had been carried out by other agents from the East India Company. However, the maps were largely based on length measurements and astronomical location determinations and were therefore imprecise and not free of contradictions. At the turn of the century, the general opinion was that the required accuracy could only be achieved with a three-dimensional, trigonometric measurement. The areas acquired by the Fourth Mysore War and the victorious siege of Seringapatam provided an occasion for this.

William Lambton's initiative

Preparations

William Lambton , a surveying officer who had taken part in the Mysore campaign, took the opportunity and proposed in 1799 that the area between the Coromandel Coast in the east and the Malabar Coast in south-west India be recorded by an accurate triangulation and a meridian arc measured. Although he soon received an order to it and ordered the necessary equipment, including a time with the necessary precision extremely rare and more vast than half a ton theodolite ; but it was not until 1802 for all instruments to arrive in Madras. The ship with the theodolite had been brought to Mauritius by a French privateer , whose commander, however, had the valuable instrument sent to the government in Madras with a polite accompanying letter .

The measuring chain for measuring the baselines was originally intended to be a gift to the Emperor of China, but this failed, so it was made available to Lambton in a detour. It was 100 feet (30.48 m) long and consisted of 40 interconnected iron bars, each 2½ feet (76.2 cm) long. When taking the length measurements, the chain was in five custom-made 20 foot (6.096 m) long wooden boxes to protect it from the sun. The boxes were stored on adjustable tripods so that the chain could be aligned to an exact straight line . With each measurement, the temperature in the boxes was measured in order to be able to take into account the expansion of the metal. Another chain was not used in the field, but was used as a control at the beginning and at the end of each measurement of a baseline.

Start of the survey

The Great Trigonometric Survey of India began on April 10, 1802 with a baseline measurement at Madras . Major Lambton chose the plain between St. Thomas Mount at its northern end and Perumbauk Hill at its southern end, on which a 7.5 mile (12.1 km) line could be established. These measurements were completed on May 22, 1802. Lambton then measured a short meridian arc near Madras and the length of a parallel that intersected it at right angles. He spent 16 nights observing the star Aldebaran alone .

A series of triangles was then measured up to the Mysore plateau . At Bangalore , an assistant of Lambton determined the length of a second baseline in 1804 to check the work to date and as a basis for the following measurements. With a series of further triangulations , including over the summit of the 1748 m high Tadiandamol, the Malabar coast was reached at the coastal towns of Tellicherry and Cannanore . This series ended in 1806. It turned out that the distance from coast to coast, which according to the previous maps had been 400 miles, was in fact only 360 miles. This 40 mile (64 km) difference proved to doubters the need for a careful basic trigonometric survey .

Surveys in southern India, continued north

Lambton then mainly turned to the meridian arc and made triangulations from Bangalore to Cape Comorin. The gate towers of temple complexes, which were provided with scaffolding and served as a high-altitude survey point, were also used. When the heavy theodolite was pulled onto such a tower in Thanjavur , a rope broke and the instrument hit the wall with great force, bending and damaging important parts. Instead of seeing the damage as irreparable, Lambton locked himself in his tent at his base in Bangalore with the theodolite in order to repair it so completely in a six-week work that it could still be used until 1830.

In 1811 the measurements of the meridian arc between Bangalore and Cape Kormorin were finished. Lambton turned to the further north over the next few years, where the triangulations were continued along the meridian arc and to various coastal locations. Lambton crossed the Tungabhadra River and came to the area of Nizam , the princely state of Hyderabad . After further surveying work, he set up a station more than 200 km further north at Bidar in 1818 in order to measure another baseline and check its exact position by means of a series of astronomical observations. As before at other locations, tests with the pendulum gravimeter were also carried out to measure the acceleration due to gravity at this location.

The work had shown that the poles used to mark the surveying points were difficult to see in the dusty haze of the dry season, but were much easier to see over longer distances in the clearer air of the rainy season. This also applied to the sun mirrors used over time. The result was that Lambton and his survey team were mainly on the move in the rainy season, even if it was then difficult to move. During this time, Lambton not only had to struggle with the difficulties of the climate, the terrain and the frequent hostility of the local population, but also had to fight back against cuts of his budget by the government in Madras and doubts about the meaning of the lavish activity.

The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India is subordinate to the Governor General

The governor-general in Calcutta finally recognized the importance of Lambton's work, placed him under his central administration on January 1, 1818, and ordered the project to be referred to as The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India in the future . At the same time, George Everest was named Lambton's chief assistant .

According to Lambton's idea of gradually expanding a comprehensive network of bases northwards, he concentrated for a long time on the land between the rivers Krishna and Godavari . Everest was sent in 1819 to survey areas infested with malaria and whose residents rebelled against their local government. Although he managed to overcome these difficulties, his health was so bad that he had to go to the Cape of Good Hope to recuperate in 1820 . In the meantime, Lambton continued to work tirelessly and extended the measurement of the meridian arc to beyond Bidar beyond the 18th parallel. But the years had left their mark on him too. While he was on his way from Hyderabad to Nagpur to continue his work , he died on January 20, 1823 in Hinganghat in what is now the Wardha district of Maharashtra .

In the more than twenty years since the beginning in Madras, Lambton had measured a meridian arc of more than 1,100 km in length and a total area of 165,342 square miles or 428,070 km².

George Everest succeeds Lambton

Continuation to Sironj

George Everest , who was working on the Bombay Triangulation Series at the time, was appointed his successor and head of the Great Trigonometrical Survey after Lambton's death. First he had personnel problems to overcome, as one colleague had died, another had left, and the majority of Lambton's people, who were from the Madras area, were unwilling to follow the surveying activity as it moved northward and move on with it away from their home. Nevertheless, he managed to continue the measurements as far as Sironj , which is around 680 km north of Bidar . Another provisional quarter was set up there and a new baseline was measured. Everest himself plagued himself with a severe fever during this time, until his condition worsened so that in 1825 he had to travel to England to relax.

During his absence, one of his employees created the more than 1,100 km long triangulation series from Sironj to Calcutta.

Stay in England

Everest used the time in England to familiarize himself with the latest developments in surveying, so that he returned to India in 1830 with the most modern equipment. In addition to the new theodolites, the most important innovation was to no longer measure the length of a baseline with chains, the temperature-related expansion of which could never be precisely determined, but with the compensation bars invented by Colonel Colby . They consisted of a brass and an iron rod, the different thermal expansion of which moved the pointers attached to their ends in such a way that a certain marking on the pointer always pointed exactly to the same point and the distance between these two points therefore always remained exactly the same.

Surveyor General

After his return, Everest took on his position as head of the Great Trigonometric Survey, as well as the office of Surveyor General of India , i.e. the management of an authority, which was difficult to coordinate with the trigonometric survey taking place in open terrain.

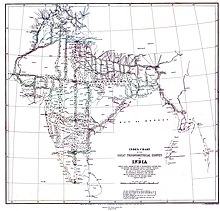

Everest had recognized that Lambton's idea of using area-wide geodetic surveys to form a network of triangles extending over the whole of India had to fail because of the size of the subcontinent. He therefore limited the large trigonometric survey to triangulation series along the longitudes and some latitudes. He attached great importance to triangles that were as uniform as possible. No angle was allowed to be smaller than 30 ° or larger than 90 °. These triangular rows at intervals of usually around 60 nautical miles or 110 km thus formed a grid that could then be filled in by simpler topographical measurements by other departments of the Survey of India, which was largely possible with the help of measuring tables . Everest not only created rules for the activity at that time, but also laid the basis for Indian surveying, which is still valid today, albeit in a modernized form, with this grid - iron .

Continuation and completion of the measurement of the meridian arc

In 1832 he resumed work on measuring the meridional arc, meanwhile reinforced by Andrew Scott Waugh , whose achievements he soon learned to appreciate. The area now reached also made new methods necessary. Lambton had found good surveying points in the hilly terrain of southern India, but had to find out that the view in the dry season was severely restricted by dust and haze and therefore worked with the clearer air predominantly in the rainy season, even if this was a considerable nuisance for those involved often also brought damage to health. Everest, on the other hand , had to artificially create virtually every survey point in the flat land in the Ganges region by building wooden towers 10 to 20 m high, the position of which was determined by a simplified, preliminary survey. Because of the hazy air, he worked with mirrors over short distances, while working longer distances at night with oil lamps reinforced with parabolic mirrors that were lit at certain intervals. Their light was hardly visible to the naked eye, but due to the preliminary measurements, the theodolite could be aligned beforehand in such a way that the light signal was captured.

At the end of 1834, work began on the northernmost part of the meridian arc with the measurement of a baseline at Dehradun in what is now Uttarakhand in the foothills of the Himalayas, which, including all tests and control measurements , took about three months. This baseline was connected to two peaks in the Siwalik Hills , from which further triangles were measured across the plain. A small astronomical observatory was also built. The northernmost survey point on Mount Banog was about 5 km northwest of the approximately 1800 m high Mussoorie and 2 km from the house that Everest had built there as his permanent quarters. At the end of 1836, two groups, one led by Everest and the other under Andrew Waugh, began to connect the baseline at Dehradun with the older baseline, about 650 km further south at Sironj. In order to obtain really exact values, this line, which was measured with chains at the time, was measured again by Sironj with the same instruments that had been used by Dehradun. In addition, a second, exactly the same observatory was built at Sironj on the same longitude as the first. In October 1838, Andrew Waugh began checking the angles measured in the Deccan years ago with the new theodolite, which lasted until June 1839. On his return to Dehradun, it was found that the length of the baseline in Dehradun, calculated by Sironj, only deviated 17 cm from the actual length. From November 1839 to late January 1840, Everest in the northern observatory and Waugh in the southern observatory took simultaneous measurements of a number of stars to determine the difference in latitude between the observatories. The same procedure was repeated the next winter between Sironj and another place around 650 km further south near the old baseline near Bidar. In addition, this old baseline was also measured again. Here, too, the length calculated by Sironj only deviated from the actual length by 10 cm.

In 1841, this work brought the measurements of the meridian arc begun by Lambton to a conclusion, which extends over more than 21 degrees of latitude between Cape Kormorin and the approximately 2500 km distant northern end at Dehradun and which became known as The Great Arc . It was one of the longest meridian arcs of the earth measurement at that time and one of the largest scientific projects of that time.

Further measurements

In addition to the measurement of the meridional arc, Everest also pursued the measurement of further lines of his iron grid , such as the 500 km long series on the latitude from Bombay to the meridional arc, as well as a series of series between the triangulation series Sironj - Calcutta , which he himself had started under Lambton and the border of Nepal .

In 1843 Everest said goodbye and returned to England.

Andrew Waugh becomes Head of Grand Trigonometric Surveyor and Surveyor General

Continuation of Everest's Iron Grid

At Everest's suggestion, Andrew Scott Waugh was appointed head of the Grand Trigonometric Survey and Surveyor General of India in 1843 . Andrew Waugh continued work on the Iron Grid ( gridiron ) established by Everest , mainly in northeastern India.

Triangulation along the Himalayas, discovery of the later Mount Everest

The longest of the numerous triangulation series was that from Dehradun eastwards along the Himalayas to the region south of Darjeeling , where another baseline was established in Sonakhoda near Jalpaiguri . Since the Nepalese government did not grant access to their territory, the work had to be carried out between 1845 and 1850 with great losses through the malaria-infested jungle and swamp areas of the Terai at the foot of the Himalayas. Forty Indian employees died in a single season. Almost half of British surveyors contracted jungle fever and died on site or in the following years.

The various surveying teams also took bearings on 79 distant high peaks of the Himalayas, some of which were still unknown to the British and nowhere precisely recorded. While the triangulation series mostly measured triangles with edge lengths of around 30 to 50 km (19 to 31 miles ) and not more than 100 km (62 mi.), Triangles with edge lengths between 130 km and more than 200 km were now obtained. The calculations of Radhanath Sikdar , who was appointed by Everest in 1831 as a mathematical assistant and who has meanwhile risen to Chief Computor of the Survey of India, came to the result in 1852 that Peak XV at 29,002 feet (8,840 m) was the highest of the targeted peaks and thus probably the highest mountain in the World is. After numerous checks and control calculations, Andrew Waugh reported this result to the Royal Geographical Society in a letter dated March 1, 1856, which was read out in their meeting on May 11, 1857. Since it was not possible to determine with certainty from a great distance what the local population called the mountain, he named it Mount Everest in honor of his predecessor .

Further series, measurements in the west

During this time Andrew Waugh's staff also carried out the triangulation series from Bombay along the coast to Goa and on the eastern coast from Calcutta to Madras, as well as other shorter series in the east within the framework of the grid laid out by Everest.

After this work, which ultimately went back to Everest, Andrew Waugh turned to the west in 1856, where the provinces of Sindh and Punjab had only recently come under the rule of the British East India Company. He planned to use the grid method to measure this area, an area whose total area was larger than that of the Iron Grid carried out by Everest.

A triangulation series was carried out between 1847 and 1853 from Dehradun northwest along the Himalayas to Attock on the Indus between Peshawar and Rawalpindi 650 km away - interrupted by local uprisings. Another began in Sironj in 1848, crossed mountains and desert areas and reached Karachi , which is well over 1,000 km away, in 1853. At both endpoints, baselines were again set up and precise location determinations carried out, with the necessary equipment and instruments first from Dehradun to Attock, then from there had to be transported to Karachi. Attock and Karachi were connected with a triangulation series that was also well over 1,000 km long, started from both locations and met in the middle. Eventually a number of series were run on the longitudes. In addition, separate leveling was carried out between Karachi and Attock on the one hand and Sironj on the other in order to determine the exact altitude of these places above sea level. This work was completed in 1860, after being interrupted by the uprising of 1857 .

Meanwhile, Captain Montgomerie began surveying Kashmir in 1855 . The triangulation series followed in the Jammu area at a height of about 350 m from the earlier series along the Himalayas. When crossing the Pir Panjal mountain range , however, heights were quickly reached where snow made the work even more difficult. After crossing the Kashmir Valley , the camps in the Karakoram were often at heights of over 5,000 m. The highest observation station was more than 6,200 m high, the highest survey point was set up at 6,547 m. In 1856 Montgomerie observed two striking peaks at a great distance from Haramukh , located on the northern edge of the Kashmir Valley, at a height of 5,142 m , which he sketched and noted as K 1 and K 2 . Subsequent measurements from various points showed that K 2, more than 200 km away, had a height of 28,278 feet (8,619 m), making it the second highest mountain in the world - which is still called K 2 today because it is known because of its remoteness could not find a local name ( K 1 was the 7,821 m high Masherbrum ). When surveying Kashmir, Captain Godwin-Austen came close to K2, where he surveyed the Baltoro Glacier . The 20 km long tributary of the Godwin-Austen glacier flowing from the K 2 to the Baltoro Glacier was later named in his honor .

Andrew Waugh planned to extend the survey eastwards from Calcutta and from the baseline at Sonakhoda to Assam , but retired in March 1861 after having directed the Grand Trigonometric Survey and the Survey of India for more than 17 years.

James Thomas Walker becomes Head of Grand Trigonometric Survey

Expansion of the network

On March 12, 1861, James Thomas Walker was appointed head of Large Trigonometric Surveying, for which he had worked since 1853. In the following two years he first completed the triangulations in northwest India. After establishing a baseline at Visakhapatnam on the east coast in 1862 , it was found that its actual length was only half an inch (about one centimeter) from the length calculated using the survey network that was 770 km away from his starting point Calcutta had and ran for long stretches through dense jungle. This baseline was connected to the Madras observatory with another triangulation series, which was reached in 1864 - 62 years after William Lambton started the big project there. Since there were now much more precise instruments than in Lambton's time, a large part of his measurements were repeated, which took a total of until 1874. Over the next two years, the Great Arc was connected to Rameswaram on the island of Pamban and connected to the Ceylon survey network via a survey point on a small, intermediate island .

Also from 1862 a triangulation series was started from Calcutta to the east. It led partly through such dense jungle that the lines of sight had to be cleared before the actual survey could begin. Several people died of jungle fever and widespread cholera. Nevertheless, the 340 km long series to the eastern border of India was completed in 1867. This series then served as the basis for further measurements of the Himalayas, along the eastern border, along the Brahmaputra to Sadiya in Assam and in a southerly direction along the coast of Burma .

During the same period, further triangulation series were carried out south of Bombay, also partly in dense jungle. In Kashmir, the surveys were advanced further into the Karakoram, here directly accompanied by the topographical surveyors, who penetrated almost all mountain valleys. The Nanga Parbat was also measured.

Completion of the large trigonometric survey

In the following years James Walker had numerous smaller, supplementary triangulation series carried out. In addition, levels were created to coordinate the altitude of different locations, pendulum tests were carried out and minor inaccuracies were corrected. With the introduction of telegraphy it became possible to determine the longitudes of many places much more precisely than was previously possible. At the headquarters in Dehradun, the calculations of the past decades were checked again.

At the time it was also decided a report on the work of the Great Trigonometric Survey of India ( Account of the Operations of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India to issue) in twenty volumes, of which the first nine volumes were published under the Walkers line since 1871 .

The Great Trigonometric Survey of India was over. In the more than 70 years since it began in Madras, many British geodesists and thousands of Indian employees, from simple porters to chief computers at headquarters, have worked for the project. A large number died of the various diseases that the stay in jungles, swamps and deserts brought with it. Perseverance and the constant striving for the greatest possible accuracy led to one of the largest surveying networks in the world at that time, which was considered to be the most accurate of its time.

James Walker was appointed Surveyor-General of India on January 1, 1878.

literature

- John Keay: The Great Arc - The Dramatic Tale of How India Was Mapped and Everest Was Named. Harper Perennial, New York 2001, ISBN 0-06-093295-3 .

- Oliver Schulz: India on foot - A journey on the 78th degree of longitude. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-421-04474-7 .

swell

Unless otherwise stated, the article is based on:

- Clements R. Markham: A Memoir on the Indian Surveys. 2nd Edition. WH Allen & Co., London 1878. archive.org

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d e Clements R. Markham: A Memoir on the Indian Surveys . 2nd Edition. WH Allen & Co., London 1878; archive.org

- ↑ a b G.F. Heaney: Rennell and the Surveyors of India. Lecture to the Royal Geographical Society, 1967. Himalayan Journal published by The Himalaya Club. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ↑ James Rennell - the father of oceanography. ( Memento of the original from May 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. National Oceanography Center, Southampton, accessed July 21, 2012.

- ↑ The beginning year given as 1764 is probably incorrect: the Survey of India names 1767 as the year of its origin.

- ↑ Map of Bengal and Bihar (16.88 MB!)

- ↑ Map of the provinces of Delhi, Agrah, Oude, and Ellahabad (10.56 MB!)

- ↑ cf. a slightly later map of South India (10.85 MB!)

- ^ Rama Deb Roy: The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India in a Historical Perspective. ( Memento of the original from March 31, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Indian Journal of History of Science. 21 (1), (1986), pp. 22-32. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ H. Manners Chichester: Lambton, William . In: Sidney Lee (Ed.): Dictionary of National Biography . Volume 32: Lambe - Leigh. , MacMillan & Co, Smith, Elder & Co., New York City / London 1892, p. 25 (English).

- ↑ a b R. Ramachandran: Survey Saga. on Frontline April 27, 2002; Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ↑ Tadiandamol in the English Wikipedia

- ↑ Thomas Frederick Colby in the English Wikipedia

- ↑ Years later, Andrew Waugh's measurements in western India showed that the constant precision of the compensation rods had its limits.

- ↑ Map of the complete grid iron ( memento of the original from October 31, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on Unlocking the Archives (Royal Geographical Society); Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ↑ The simultaneous measurements eliminated any errors in the cataloged positions of the stars.

- ↑ Soutik Biswas: The man who 'discovered' Everest. on BBC News online, accessed September 4, 2012.

- ↑ Andrew Waugh: Letter to the Royal Geographical Society dated March 1, 1856 . In: Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London, no.IX. P. 345. (Digitized on GoogleBooks)

- ^ Markham: A Memoir on the Indian Surveys . Pp. 116, 121.

- ↑ Because of this naming, the K 2 was incorrectly referred to as Mount Godwin-Austen on numerous maps .

- ↑ Colonel Thuillier was appointed Surveyor General.

- ↑ Extensive collection of the Survey of India Report Maps on the PAHAR Mountains of Central Asia Digital Dataset website