When all the fountains flow

When all the Brünnlein flow is a German love song , the text of which has been documented in parts since the 16th century and has been known in its current text version since it was included in Friedrich Silcher's collection of songs in 1855. A melodic version that differed slightly from that used by Silcher became established in the mid-19th century. In this version the song is still one of the most famous folk songs in the German-speaking world.

history

A love song entitled Die Brünnlein, who flow there , the text of which largely corresponds to that of the first and second stanzas of Wenn alle Brünnlein flow , was recorded by Leonhard Kleber in 1520, including the melody. In 1534, the Nuremberg publisher Hans Ott published the song collection Hundert und Zwanzig Newe songs with four-part choral movements, the number 44 of which is the said song. As a result, the song was published repeatedly in slightly different versions, for example by Hans Peterlein ( Johannes Petreius ) in Nuremberg in 1541 and by Ivo de Vento with Adam Berg in Munich in 1570.

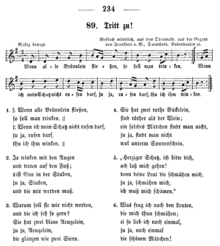

Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim recorded a text variant in Des Knaben Wunderhorn . In 1855 Friedrich Silcher published the song Wenn alle Brünnlein flow in the text version known today with four stanzas in one movement for four voices. The melody largely corresponds to today's version, but differs slightly in the second part of the stanza. The text, but not the melody, largely corresponds to the song published in 1534. " Swabia " is given imprecisely as origin . Published in Ludwig Christian Erks Deutsches Liederhort in 1856 under the title Tritt zu! Both when all the wells flow (No. 89) with a different melody and the indication of origin "Odenwald, area of Frankfurt am Main, Darmstadt, Babenhausen" and The little wells that flow there without melody (No. 89a). In the expanded edition of the Liederhort (1893), Franz Magnus Böhme lists further text and melody variants from Upper Hesse, the Dill and Lahn districts and from Brauerschwend in Hesse-Darmstadt.

The first part of today's melody is one of the melody elements that often "wandered" in the 18th and 19th centuries. The beginning bears great resemblance to Papageno's aria “A Girl or Female” from Mozart's Magic Flute (1791). This melody, in a modified form, was soon added to the song Üb 'immer Treu und Righteousness by Ludwig Hölty . The spiritual folk song I Am A Weidmann also has the same melody beginning. In 1840 Anton Wilhelm von Zuccalmaglio printed the text of the Brünnlein together with the melody in his German folk songs . The melody used by Silcher was also included in the General German Kommersbuch of the student associations . With this or a very similar melody, the song became one of the most frequently sung and printed songs in the German-speaking area during the 19th and 20th centuries. The melody versions sung most frequently today differ somewhat in the second half of the melody. At the point “If - I am not allowed to call my darling” (fifth from last and fourth from last measure) the note either goes down an octave or remains up in the melody, while all other measures including the last four measures are the same in both versions.

Independent settings of the text created u. a. the composers Simon Breu , Carl Heffner , Carl Isenmann , Hugo Richard Jüngst and Karl Schauss .

Content of the lyrics

The water of the fountain - a spring or a stream - is a symbol for feelings, as it also appears in other love songs such as Am Brunnen vor dem Tore or And in der Schneegebirge . As the title "secret love" used in the 19th century implies, the author praises a young woman with whom he has fallen in love, but is not allowed to openly show it. In addition to the wink of the eye ("Winken mit den Augen / Äugelein"), the second stanza also mentions "kicking with the foot". This is a possible contact with the feet, which are located below the table at which the participants are sitting. According to information from John Meier (1936), the founder of the German Folk Song Archive , in the Middle Ages, if a woman replied to "step on the foot", it meant that she gave the man a promise of marriage. In the two following stanzas not yet included in the song of the 16th century, the beauty of the beloved and the hope of winning her as a woman are sung about.

Text and melody

A version of the song known today reads:

1.

When all the fountains flow,

one must drink;

if I can't call my darling,

I'll wave to him.

2.

Yes, wave your eyes

and step on your foot, there

's one in the room

that must be mine.

3.

Why shouldn't she be,

I like her so much.

She has two blue eyes that

shine like two stars.

4.

It has two red cheeks and

is redder than the wine.

You won't find a girl like that in the

sunshine.

The most famous melody today is:

Slightly different from this, the Zupfgeigenhansel and Bube Dame König sang:

The fountains that flow there

The text of the song Die Brünnlein, which flow there from the 16th century, reads:

1.

The little fountains that flow there

are to be drunk,

and whoever has a steadfast courtship

shall wave to him;

2.

Yes, wave

your eyes

and step on

your foot: it is an honorable order that

must avoid its wooing.

Counterfactor in the 16th century

The song was already the subject of counterfactor in the 16th century . The following sacred song was published in Leipzig in 1586, set for four voices in 1588:

1.

The fountain of mercy flows, it

should be drunk.

O sinner, you shall atone,

God beckons you

2.

with his kind eyes

and straighten your foot

through the word of faith that

Christ alone has to help you.

Web links

- Free scores of When all the little spring flow in the Choral Public Domain Library - ChoralWiki (English)

- Free scores of When all the little spring flow in the Choral Public Domain Library - ChoralWiki (English)

- Georg Nagel (2016): When all the wells flow, folk song (16th century), folk tune (18th century) , Lieder-Archiv.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ The little brothers. In: One hundred and twenty-one newe songs . Hans Ott, Nuremberg 1534. No. 44.

- ↑ Achim von Arnim, Clemens Brentano: Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Volume 2. Winter, Heidelberg 1808, p. 193 f. ( Digitized in the German text archive ).

- ↑ Friedrich Silcher: Twelve folksongs, set for four male voices. 11th issue . Laupp and Siebeck, Tübingen 1855. (Note: a total of 12 booklets.)

- ↑ Sheet music in the public domain of Wenn alle Brünnlein flow in the Choral Public Domain Library - ChoralWiki (English)

- ^ A b Ludwig Christian Erk : Deutscher Liederhort. Selection of the excellent German folk songs from the past and present with their peculiar melodies. Published by Ludwig Erk . Th. Chr. Fr. Enslin, Berlin 1856, p. 234 f. ( Digitized on Wikisource ).

- ↑ Ludwig Erk, Franz Magnus Böhme (Ed.): Deutscher Liederhort. 2nd volume. Breitkopf and Härtel, Leipzig 1893, pp. 247–250 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ See Wilhelm Tappert: Wandering melodies. A musical study. 2nd Edition. Brachvogel & Ranft, Berlin 1889 ( archive.org ).

- ^ Franz Wilhelm Freiherr von Ditfurth (Hrsg.): German folk and society songs of the 17th and 18th centuries. CH Beck, Nördlingen 1872, p. 213 f. ( Digitized in the Google book search).

- ↑ German folk songs with their original tunes. With the help of Professor E. Baumstark and several other friends of folk poetry, collected as a continuation of A. Kretzschmer 's work and annotated by Anton Wilhelm von Zuccalmaglio. Second part. Association bookstore, Berlin 1840. P. 361 f. ( Digitized in the Google book search).

- ↑ General German Kommersbuch . Moritz Schauenburg, Lahr / Black Forest 1896 to 1906. No. 541. Secret love .

- ↑ a b c Georg Nagel (2016) When all the little fountains flow, folk song (16th century), folk tune (18th century). Lieder-Archiv.de.

- ↑ a b When all the fountains flow, Text: Friedrich Silcher , CD Traumländlein. New folk music from the Saale to the Irish Sea. Band Jack Dame König , accessed April 8, 2019.

- ↑ When all fountains flow on YouTube , sung by Bube Dame König , accessed on April 10, 2019.

- ↑ When all the wells flow on YouTube , sung by Zupfgeigenhansel , accessed on April 10, 2019.

- ↑ When all the wells flow at TheLiederNet Archive, accessed on April 11, 2019

- ↑ The most beautiful treasure (When all the brooks flow) at TheLiederNet Archive, accessed on April 11, 2019

- ↑ Cf. Otto Holzapfel : “Intercultural idioms and their cultural-historical background. 'Get on someone's roof' and 'step on someone's foot': a sketch ”, in: Diyalog. Intercultural journal for German studies [Internet edition], 2013/2, pp. 95-102. Cf. on the song "Wenn alle Brünnlein flow ..." Otto Holzapfel : Song directory: The older German-language popular song tradition ( online version on the Upper Bavarian Folk Music Archive homepage ; in PDF format; ongoing updates) with further information.

- ↑ Carl von Winterfeld: The Protestant Church Chant and its relationship to the art of composition, Volume 1 . Breitkopf and Härtel, Leipzig 1843, p. 88.