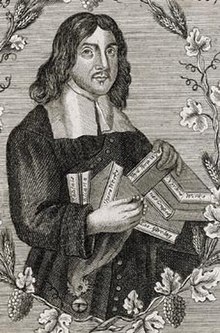

William Winstanley (Author)

William Winstanley (* 1628 in Quendon , Kingdom of England ; † December 22, 1698 ibid) was an English poet , satirist , historian and publicist . In addition to important works such as Lives of the most Famous English Poets , which contained the biographies of famous English poets of his time, Winstanley also campaigned for the restoration in England after Cromwell's death . He also created numerous satirical writings such as Poor Robin's Almanack .

Life

Childhood and Adolescence (1628–1649)

William Winstanley was born in Quendon ( Essex ) in 1628 as the third of eight children to the wealthy yeoman William Winstanley and his wife Elizabeth (née Leader). Winstanley received a basic education in Latin, mathematics, and history at home. He developed an interest in literature at an early age, but was urged by his father to begin a solid technical training in order to secure himself materially. At the age of 14 Winstanley was sent to Saffron Walden to live with his uncle William Leader and his wife Mary, where he began an apprenticeship as a cloth merchant until 1649. Leader supported his literary ambitions and granted him multiple trips to London, during which Winstanley did research for his later work England's Worthies . The English Civil War fell during Winstanley's apprenticeship , in the latter phase of which he joined the loyal Cavaliers for a short time .

Journalistic beginnings (1649–1698)

After completing his apprenticeship, Winstanley was raised to the civil status of Saffron Walden in 1649. In 1650 he married his first wife Martha and moved with her to Creepmouse Alley in Saffron Walden. At the end of 1651 they had a son, Will, from whose birth Martha could not recover and died in early 1652. William Winstanley therefore married Anne Prime from Cambridge in 1653 , with whom he had two other children, Thomas and Anne. From 1650 Winstanley continued to help out in William Leader's drapery shop, but also worked as a publicist. His first work, The Muses Cabinet , was published in 1655. With the end of the Republic of England in 1659, Winstanley now publicly expressed himself as a supporter of royalty. In the same year England's Worthies was published , which brought together the biographies of famous English kings, nobles, clergy and poets. He wrote several books, poems and calendars, which he initially published under his own name and from 1661 under the name Poor Robin ("poor Robin"). The satirical Poor Robin's Almanac became one of Winstanley's most successful publications from 1664: the annually published almanac was in the style of a peasant calendar that was widely used at the time, but dispensed with the astrological and popular rules that usually formed its content. Instead, they contained puzzles, jokes, recipes, local gossip and stories, with which they found wide audiences and became a commercial success. In the 1660s, Winstanley eventually opened an office in London's Queen’s Head Tavern on Snow Hill , where he met with his publishers and London colleagues.

Martha Winstanley died in 1691. William Winstanley fell ill with smallpox in December 1698 and died on December 22 of that year.

plant

Political and social engagement

Although he wrote a relatively unbiased assessment of the person of Cromwell in England's Worthies in 1659 , Winstanley became a declared royalist at the latest after the Stuart Restoration, who campaigned for the restoration of the old order. In The Loyall Martyrology: or Brief Catalogs and Characters of the most Eminent Persons who suffered for their Conscience during the late times , he summarized the names and biographies of those who were executed by order of the Rump Parliament, including Charles I , the father by Charles II. With this he created an important work in support of the indictment against the subversives of the English Civil War. Winstanley also campaigned to revive English traditions that had been abolished or forbidden among the Puritans.

In this way he persuaded the king not only to lift the ban on Christmas festivities issued by the rump parliament in 1644 , but also to work specifically to revive the festival. The Puritans had, among other things, the Christmas Mass abolished, banned all celebrations and for 25 December strict fasting prescribed. Although these provisions became obsolete with the accession of Charles II to the throne, the strict punishment of Christmas celebrations meant that Christmas was hardly celebrated in many places. Winstanley saw this not only as a loss of valuable traditions, but also feared the social consequences of the lack of alms and care for the needy at Christmas. Not only did he write a series of writings on Christmas customs, Advent carols, and appeals to mercy that were sold in Winstanley's bookstore in Saffron Walden , but he also persuaded the king and members of the nobility to hold meals for the poor at their property at Christmas. As a result, by the end of the 1680s, Christmas was again widespread in all parts of England, with Winstanley having a lasting impact on English Christmas traditions.

Working as an author and publicist

Winstanley stood out for his comments on historical and contemporary people, whose biographies he dealt with in England's Worthies (1660), The Loyall Matyrology (1665) or The Lives of the most Famous English Poets (1687). The latter is particularly important as a compilation and assessment of English poets from the perspective of the 17th century. Although already had Edward Phillips 1675 Theatrum Poetum published a compilation English poet biographies, took over from the Winstanley on top of that a large number of entries and more than 100 of Phillips' poets not treated. The importance of Winstanley's work in this case, however, lies in his approach to taking over Phillips' work. Not only did he arrange the biographies chronologically for the first time, but, unlike Phillips, in many cases also dealt critically with sources. While Phillips usually relied on secondary sources, Winstanley usually read the works of the poets he describes himself. In addition, although only an amateur historian, he re-examined Phillips' sources again, which often enabled him to gain more knowledge about a poet than Phillips himself .William Parker sees in Winstanley an author who, in contrast to Phillips, was primarily driven by the enthusiasm for the work of the poets, while Phillips merely strung together names and titles.

Winstanley was also active as a satirist and chronicler of the society of his time. In addition to various mocking comments on fellow poets and the historical rarities and curious observations , Winstanley also counts the Poor Robin series, the first edition of which appeared in the early 1660s in the vicinity of Winstanley's home Saffron Walden and which contained numerous joke poems and anecdotes. With "Poor Robin" Winstanley also signed a portrait of himself in an issue of Poor Robin . This series of " Almanacks " found huge sales and was continued after Winstanley's death and reprinted into the 19th century.

Winstanley is also suspected of being the author in connection with the events surrounding the Henham kite : together with his nephew Henry , he is said to have built a mechanical dummy dragon in 1668, which terrified the population of the village of Henham near Saffron Walden. Subsequently, in order to make the hoax perfect , Winstanley is said to have anonymously written a pamphlet in which the events are reported and which lists several eyewitnesses - all friends and acquaintances of Winstanley. Poor Robin's Almanack also reported about this "dragon" in 1674.

Works (selection)

- The Muses Cabinet, stored with variety of poems. 1655

- England's Worthies: select lives of the most eminent persons. 1659, 1684

- Poor Robin. An Almanack after a new fashion. 1664

- The Loyall Martyrology: or Brief Catalogs and Characters of the most Eminent Persons who suffered for their Conscience during the late times. 1665

- The honor of the Merchant Taylors. 1668

- The new help to discourse: or wit, mirth, and jollity intermixed with more serious matters. 1669.

- Poor Robin's intelligence. 1676-78

- Poor Robin's dream, or the visions of Hell. 1681.

- England's Worthies. 1684

- Historical rarities and curious observations domestick & foreign. 1684

- The lives of the most famous English poets, from the time of William the Conqueror to James II. 1687

- The Essex champion: or the famous history of Sir Billy of Billercay. 1699

- Poor Robin's true character of a scold: or, The shrew's looking-glass: Dedicated to all domineering dames, wives rampant, cuckolds couchant, and hen-peckt sneaks, in city or country. 1678

- The lives of all the Lords Chancellors, Lords Keepers and Lords Commissioners of the Great Seal. 2 volumes, 1708, 1712

References and referrals

literature

- Alison Barnes: The Ingenious William Winstanley. Poet, Journalist, Bookseller, Historian and Novelist of Saffron Walden 1628 - 1698 . Uttlesford District Council , Saffron Walden 1998, ISBN 0-905993-41-1 .

- Sidney Lazarus Lee : Winstanley, William . In: Sidney Lee (Ed.): Dictionary of National Biography . Volume 62: Williamson - Worden. , MacMillan & Co, Smith, Elder & Co., New York City / London 1900, pp. 209 - 211 (English, (full text in the English-language Wikisource ) ).

- George Monger: Dragons and Big Cats . In: Folklore . tape 103 (2) , 1992, pp. 203-206 , doi : 10.1080 / 0015587X.1992.9715842 .

- William Riley Parker: Introduction . Foreword to the new edition of English Poets , Scholar's Facsimiles and reprints, Gainesville 1963. ( Online at Project Gutenberg )

- Tony Rennell: William Winstanley: The man who saved Christmas from Cromwell's misery . In: Mail Online , December 19, 2009.

Web links

- Works by William Winstanley in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available to users from Germany )

- Wiliam Winstanley in English Poetry 1579–1830: Spenser and the Tradition , a project by the Center for Applied Technologies in the Humanities of Virginia Tech

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Sidney Lazarus Lee : Winstanley, William . In: Sidney Lee (Ed.): Dictionary of National Biography . Volume 62: Williamson - Worden. , MacMillan & Co, Smith, Elder & Co., New York City / London 1900, pp. 209 - 211 (English, (full text in the English-language Wikisource ) ).

- ↑ Barnes 1998, pp. 1-5.

- ↑ Barnes 1998, p. 5.

- ^ Tony Rennell: William Winstanley: The man who saved Christmas from Cromwell's misery. Mail Online , December 19, 2009.

- ^ William Riley Parker: Introduction , foreword to the new edition of English Poets , Scholar's Facsimiles and reprints, Gainesville 1963.

- ↑ George Monger: Dragons and Big Cats. In: Folklore , Vol. 103, No. 2 (1992), pp. 203-206.

- ↑ Henham Dragon ( August 8, 2009 memento in the Internet Archive ) at henham.org (accessed October 24, 2009).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Winstanley, William |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English poet, historian and satirist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1628 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Quendon |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 22, 1698 |

| Place of death | Quendon |