Xanthippe

Xanthippe ( ancient Greek Ξανθίππη ; born in the later 5th century BC; died in the 4th century BC) was the wife of the Greek philosopher Socrates (469–399 BC) while little information is available about the historical person and, at best, must be developed, numerous anecdotes about Xanthippe circulated in antiquity. They largely determined the image gained of her, so that she has entered European literature as the epitome of the quarrelsome " woman ". Her name is often used literally and stands for a bad-tempered, argumentative and, in contrast to her husband, moody woman, often related to the partnership.

Sources

The main sources for Xanthippe are Xenophon's Symposium and Memorabilia and Plato's Dialogue Phaidon . Both were contemporaries and students of Socrates. You mention Xanthippe on the occasion of philosophical discussions or to underline the authenticity of a described scene. All other mentions of Xanthippes are of a much later time, of anecdotal character and pick up on her jealous, rigid nature, which at that time was already stylized into a topos . Mention should be made of Aelian , who briefly mentions them in his Colorful Stories , Plutarch , who, however, only devotes himself to the question of whether Socrates also had a second wife named Myrto , but above all Diogenes Laertios , who in the 3rd century AD in passed on several anecdotes about Xanthippe to his life and teachings of famous philosophers , also devoted himself extensively to the question of Myrto and with his work significantly determined the image of Xanthippes in posterity. Anecdotal information can also be found in Athenaios . The Church Fathers hardly offer anything new on their own, like John Chrysostom only exacerbate the tenor known from the anecdotes, Hieronymus names them in a catalog of malicious women. Mention in the Suda is ineffective .

Life

The origin and year of birth of Xanthippes are just as unknown as any details of her life or the year of her death. Xanthippe was married to Socrates and had three sons with him: Lamprokles , who was a youth when Socrates 399 BC. Was executed, as well as Sophroniskos and Menexenos , both still children at the time who could be carried in the arms by their mother. According to this, Xanthippe becomes in the later 5th century BC. Their date of death is after that of Socrates in the 4th century BC. Chr.

According to a story that was spread especially among Diogenes Laertios, whose author is alleged to have been Aristotle , Sophroniskos and Menexenus came from Socrates' association with Myrto, an impoverished widow whom he had taken into his household. But this was already referred to the world of fable by Panaitios in antiquity .

The ancient tradition agrees that Lamprokles was the son of Xanthippes. From the fact that it was not Sophroniskos , the father of Socrates, who was the namesake of the firstborn, but the father of Xanthippes, one inferred that they came from a family that was superior to that of Socrates. Since Christoph Martin Wieland, one would also like to see a reference to an upscale origin in her name . The male form of the name Xanthippos was widespread mainly among the Athenian noble family of the Alkmaeonids . Furthermore, Aristophanes made fun of the naming with -hippos in his clouds for precisely this reason, which Wieland already pointed out. Xanthippe had the Athenian citizenship, so her son could become a full citizen of the Athens Polis and she was allowed to attend the theater performances as a spectator .

character

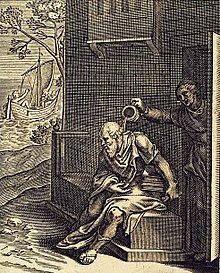

Socrates had inherited a small fortune and property in the suburb of Alopeke from his parents , which enabled him and his family to have a modest but independent livelihood. He used this to pursue his philosophical way of life and to avoid a livelihood occupation. This way of life, which even in Plato's brief mentions of Xanthippes, was the reason to put a hint of her nagging in the picture, has been cited since Wieland as an excuse for the image of the angry, contentious Xanthippe already sketched out by Xenophon. At the same time, both Xanthippe are described above all as a mother who is concerned about the welfare of her children. In Plato's case, she and her children visit her husband twice on the day of his execution in prison to bid him farewell. The bad mood of the Xanthippe described in Xenophon 's fictitious conversation between Socrates and his son Lamprokles is also defended by Socrates, since it only serves the best of the son. Only in the symposium does Socrates admit the stubbornness of Xanthippus:

"If you are of this opinion, Socrates," said Antisthenes, why is it that you do not test your xanthippe but help yourself with a woman who, under all living, yes, I consider all who lived before, and will live in the future, which is most unbearable. This happens for the same reason, replied Socrates, why those who want to become good riders do not get the gentlest and most manageable horses, but rather wild and irrepressible horses; for they think that if they can keep them in check it will be easy for them to deal with all the others. That's exactly how I did it because I wanted to make the art of dealing with people my main business: I got this woman because I was certain that if I could endure her, I would easily find myself in all other people. "

Friedrich Nietzsche led this to the less advantageous characterization:

“Socrates found a woman he needed - but he would not have looked for her either, if he had known her well enough: the heroism of this free spirit would not have gone that far either. In fact, Xanthippe drove him more and more into his peculiar occupation by making his house and home indomitable and uncanny: she taught him to live in the alleys and everywhere where one could gossip and be idle, thus making him the greatest Athenian Alley dialectician out: who in the end had to compare himself with an intrusive brake that a god had put on the neck of the beautiful horse Athens so as not to let it come to rest. "

How much Xanthippe was fond of her husband is indicated in the prison scene with Plato. There she lets his friends lead Socrates home, which accompanies Xanthippe with screams and gestures of pain, feelings of genuine affection.

Anecdotal

Among the anecdotes given by Diogenes Laertios is the parable with the horse tamer (Greek Hippocrates ) and the story that Xanthippe had torn the coat from Socrates' body in the market. When the bystanders advised him to finally get violently against his wife, he replied that this would probably please the people at the market, who would then - divided into two camps - cheer on part Socrates and part Xanthippe. According to Aelian, they both shared a single coat, which is why Xanthippe had to stay indoors whenever Socrates was out on his philosophical excursions.

The anecdote about the chamber pot also goes back to Diogenes Laertios. After the insulting Xanthippe had doused him with the chamber pot, Socrates said: “You see, when my wife thunders, she also donates rain!” All these anecdotes cultivate the allegedly bipolar relationship of the quarrelsome woman with her wise husband, which is included in the school books and was shortened to the saying:

"Xanthippe was a bad woman, the quarrel was a pastime for her."

Athenaeus still remembers that, during one of her outbursts of anger, Xanthippe trampled on a cake that had been sent to Socrates by Alcibiades . Socrates responded laconically by pointing out that she, too, no longer had any part in the cake. According to Athenaeus, the story goes back to the stoic Antipater of Tarsus , who like Socrates, albeit voluntarily, died of a poison cup.

reception

In addition to the anecdotal stories about Xanthippe and her relationship to Socrates, it also found its way into Greek fiction during the Roman Empire . In the so-called Sokratikerbriefe , a late 2nd or early 3rd century epistolary novel about Socrates and the Socratics, she is the recipient of a letter from Aeschines in the 21st letter . It is mentioned again and again, belongs to the action environment, but sometimes only serves as a pure foil for Socrates. Above all, Xanthippe becomes an independent philosopher who, in her lack of need, takes Cynical positions and, like a philosopher, wears an - old - coat. It follows the very Socratic philosophy and attitude to life, which cannot be inserted into the role of woman and mother, but rather requires an admonition to take care of clothes and children. Nevertheless, she is seen as a “good woman”.

Medieval lexicographers took what they found and passed on the anecdotes. Most of it is contained in the writing Liber de vita et moribus philosophorum associated with the name Walter Burleywe , and Vincent von Beauvais in his Speculum historiale and John of Wales in the Compendiloquium Xanthippe. An exception is the characterization by Christine de Pizan , who in her Le Livre de la Cité des Dames (“The Book of the City of Women”) published in 1405 depicts Xanthippes as an exemplary, patient wife.

Since the Enlightenment, attempts have been made to reassess the role of the xanthippe. The tendencies are clearly opposite. They either hold on to the traditional image, which serves as a foil for male-dominated philosophizing, or recognize Xanthippe as an independent person, whose work and style is appropriated, especially in feminist literature.

In the explanation of his translation Socratic Conversations from Xenofon's memorable news of Socrates' understanding of Xanthippes, Wieland already showed restrained in the explanation of his translation, Socratic Conversations , published between 1799 and 1802 . He saw in her a “stately Amazon figure [...]; of a quick, easily quick-tempered temperament, somewhat belligerent and likes to keep the last word; Incidentally, a hard-working, industrious, attentive housemother who strictly adheres to good discipline and order. ”According to Wieland, Socrates could“ easily get used to the smoke for the sake of the fire ”with such a courageous woman.

In 1865, the theologian and philosopher Eduard Zeller published his small treatise On the Rescue of Honor of the Xanthippe in his lectures and treatises of historical content. He too paints an understanding picture of Xanthippus, who, in his interpretation of the tradition, “must have been a very desirable housewife”. In Zeller's time, however, some women would have "thundered" even more forcefully if they had been married to a Socrates. Fritz Mauthner wrote a novel in 1884 under the title Xanthippe. A true story from ancient times and the present - "a salvation of honor for the main character, who is drawn here with great care and sympathy".

Trivia

According to the German spelling table , the word Xanthippe is used to spell the letter X. The asteroid (156) Xanthippe , a crater of Venus and a genus of the predatory mite family Ascidae were named in her honor.

literature

- Debra Nails: The People of Plato. Indianapolis / Cambridge 2002.

- Wolfgang Strobl : Xanthippe. In: Peter von Möllendorff , Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 8). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02468-8 , Sp. 1035-1048.

- Michael Weithmann: Xanthippe and Socrates. Eros, marriage, sex and gender in ancient Athens. A contribution to higher historical gossip. dtv, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-423-34052-5 .

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ The Greek name is derived from ξανθός xanthós "blond" and ἵππος híppos "horse".

- ↑ Xenophon, Symposium 2.10.

- ↑ Xenophon, Memorabilia 2, 2, 7-9.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo 60a-b, 116b.

- ↑ Aelian, Varia historia 7.10; 11.12.

- ↑ Plutarch, Aristides 11:12.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 2:26, 36-37 ( digital version of the German translation by Otto Apelt ).

- ↑ Athenaios, Deipnosophistai 13,555 D. 643 F,

- ↑ John Chrysostom, Homilies on the First Letter to the Corinthians, Homily 26 : 8.

- ↑ Hieronymus, Adversus Iovinianum 1.48.

- ↑ Suda , keyword Σωκράτης , Adler number: sigma 829 , Suda-Online

- ↑ Plato, Apologie des Sokrates 34d; Phaedo 116b.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 2.26; so also Suda, keyword Σωκράτης , eagle number: sigma 829.

- ↑ Panaitios with Plutarch, Aristides 11,12, to whom Plutarch rather believes; Athenaios, Deipnosophistai 13,555 D, also speaks out against the possibility of Socrates' bigamy, which is assumed in this context .

- ↑ John Burnet : Plato's Phaedo. Clarendon, Oxford 1911, p. 59 to 60a, 2 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Michael Weithmann: Xanthippe and Sokrates. Eros, marriage, sex and gender in ancient Athens. A contribution to higher historical gossip. 2nd Edition. dtv, Munich 2005, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Aristophanes, The Clouds 60–64.

- ↑ Christoph Martin Wieland: Xenophon: Socratic conversations from Xenofon's memorable messages from Socrates. Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1998 ( online in the Gutenberg-DE project ).

- ^ Michael Weithmann: Xanthippe and Sokrates. Eros, marriage, sex and gender in ancient Athens. A contribution to higher historical gossip. 2nd Edition. dtv, Munich 2005, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Plato, Phaidon 60b.

- ↑ Xenophon: Socratic Conversations from Xenofon's Memorable Messages from Socrates. 2. Conversation between Socrates and his son Lamprokles in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ↑ Xenophon : Banquet. 2. Conversation between Socrates and Antisthenes in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, Menschliches, Allzumenschliches. A Book for Free Spirits , 1878, No. 433

- ↑ Plato, Phaidon 60b.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 2.37.

- ↑ Aelian, Varia historia 7.10.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 2.36.

- ↑ Eduard Zeller : To save the honor of the Xanthippe. In: the same: lectures and treatises of historical content. Fues, Leipzig 1865, pp. 51–61, here p. 52.

- ^ Athenaios, Deipnosophistai 13, 643 F.

- ↑ For the epistolary novel of the Socratic letters and the role of the Xanthippe see Timo Glaser: Paulus als Epistle novel. Studies on the ancient epistle novel and its Christian reception in pastoral letters. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2011, pp. 135–140.

- ↑ Hermann Knust: Gualteri Burlaei liber de vita et moribus philosophorum. Laupp, Tübingen 1886, pp. 115-118 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ On the medieval Xanthippe reception, see for example Sandra Vecchio: Les deux épouses de Socrate. Les philosophes et les femmes dans la littérature des Exempla. In: Thomas Ricklin (Ed.): Exempla docent. Les examples des philosophes de l'antiquité à la renaissance (= Ètudes de philosophie médiévale. Volume 92). Actes du colloque international 23–25 October 2003, Université de Neuchâtel. Vrin, Paris 2006, pp. 225-239.

- ↑ Christine de Pizan: The book of the city of women. 2nd Edition. Orlando Frauenverlag, Berlin 1987, p. 161; see Michael Weithmann: Xanthippe and Sokrates. Eros, marriage, sex and gender in ancient Athens. A contribution to higher historical gossip. dtv, Munich 2003, p. 195.

- ^ Michael Weithmann: Xanthippe and Sokrates. Eros, marriage, sex and gender in ancient Athens. A contribution to higher historical gossip. dtv, Munich 2003, pp. 201-214.

- ↑ On the modern reception Wolfgang Strobl : Xanthippe. In: Peter von Möllendorff , Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 8). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02468-8 , Sp. 1035-1048.

- ↑ Christoph Martin Wieland: Xenophon: Socratic conversations from Xenofon's memorable messages from Socrates. Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1998 ( online ).

- ↑ Eduard Zeller: To save the honor of the Xanthippe. In: the same: lectures and treatises of historical content. Fues, Leipzig 1865, pp. 51–61, here p. 55 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Eduard Zeller: To save the honor of the Xanthippe. In: the same: lectures and treatises of historical content. Fues, Leipzig 1865, pp. 51–61, here p. 59.

- ^ Fritz Mauthner: Xanthippe. Minden, Dresden 1884, new edition in: the same: Selected writings. Volume 2. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart / Berlin 1919 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Wolfgang Strobl: Xanthippe. In: Peter von Möllendorff, Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music . Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, Sp. 1041.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Xanthippe |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Wife of Socrates |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 5th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 4th century BC Chr. |