User talk:Jamshop and Language: Difference between pages

m Reverted edits by 74.75.114.215 (talk) to last version by BorgQueen |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{otheruses4|the properties of language in general|the use of language by humans|natural language|the linguistics journal|Language (journal)}} |

|||

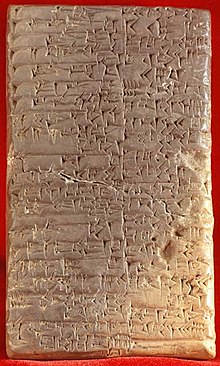

[[Image:Cuneiform script2.jpg|thumb|right|220px|[[Cuneiform]] was the first known form of [[written language]], but spoken language is believed to predate writing by tens of thousands of years at least.]] |

|||

A '''language''' is a dynamic set of visual, auditory, or tactile [[symbol]]s of [[communication]] and the elements used to manipulate them. ''Language'' can also refer to the use of such systems as a general [[phenomenon]]. Language is considered to be an exclusively human mode of communication; although other animals make use of quite sophisticated communicative systems, none of these are known to make use of all of the properties that linguists use to define language. |

|||

In [[Western Philosophy]], language has long been closely associated with [[reason]], which is also a uniquely human way of using symbols. In [[Ancient Greek]] philosophical terminology, the same word, ''[[logos]]'', was used as a term for both language or speech and reason, and the philosopher [[Thomas Hobbes]] used the English word "speech" so that it similarly could refer to reason, as will be discussed below. More commonly though, the [[English language|English]] word "language", derived ultimately from ''lingua'', [[Latin]] for [[tongue]], typically refers only to expressions of reason which can be understood by other people, most obviously by speaking. |

|||

==Speedy deletion of [[:Unworry]]== |

|||

[[Image:Ambox warning_pn.svg|48px|left]] A tag has been placed on [[:Unworry]], requesting that it be speedily deleted from Wikipedia. This has been done under [[WP:CSD#G1|section G1 of the criteria for speedy deletion]], because the page appears to have no meaningful content or history, and the text is unsalvageably incoherent. If the page you created was a test, please use the [[Wikipedia:Sandbox|sandbox]] for any other experiments you would like to do. Feel free to leave a message on my talk page if you have any questions about this. |

|||

== Properties of language == |

|||

If you think that this notice was placed here in error, you may contest the deletion by adding <code>{{tl|hangon}}</code> to '''the top of [[:Unworry|the page that has been nominated for deletion]]''' (just below the existing speedy deletion or "db" tag), coupled with adding a note on '''[[ Talk:Unworry|the talk page]]''' explaining your position, but be aware that once tagged for ''speedy'' deletion, if the article meets the criterion it may be deleted without delay. Please do not remove the speedy deletion tag yourself, but don't hesitate to add information to the article that would would render it more in conformance with Wikipedia's policies and guidelines. Lastly, please note that if the article does get deleted, you can contact [[:Category:Wikipedia administrators who will provide copies of deleted articles|one of these admins]] to request that a copy be emailed to you. <!-- Template:Db-nonsense-notice --> <!-- Template:Db-csd-notice-custom --> [[User:Seba5618|Seba5618]] ([[User talk:Seba5618|talk]]) 07:14, 13 October 2008 (UTC) |

|||

A set of commonly accepted symbols is only one feature of language; all languages must define the structural relationships between these symbols in a system of [[grammar]]. Rules of grammar are what distinguish language from other forms of communication. They allow a finite set of symbols to be manipulated to create a potentially infinite number of grammatical utterances. |

|||

Another property of language is that its symbols are [[arbitrary]]. Any concept or grammatical rule can be mapped onto a symbol. Most languages make use of sound, but the combinations of sounds used do not have any ''inherent'' meaning – they are merely an agreed-upon convention to represent a certain thing by users of that language. For instance, there is nothing about the [[Spanish language|Spanish]] [[word]] ''{{lang|es|nada}}'' itself that forces Spanish speakers to convey the idea of "nothing". Another set of sounds (for example, the English word ''nothing'') could equally be used to represent the same concept, but all Spanish speakers have acquired or learned to correlate this meaning for this particular sound pattern. For [[Slovene language|Slovenian]], [[Croatian language|Croatian]], [[Serbian language|Serbian]] or [[Bosnian language|Bosnian]] speakers on the other hand, ''{{lang|hr|nada}}'' means something else; it means "hope". |

|||

This arbitrariness does not, however, apply to words with an [[onomatopoetic]] dimension (i.e. words that to some extent simulate the sound of the token referred to). For example, the bird [[cuckoo]]'s name was indeed not given arbitrarily. |

|||

== Origins of language == |

|||

{{main|Origin of language}} |

|||

Even before the [[Theory of Evolution]] made discussion of more animal-like human ancestors common place, philosophical and scientific speculation concerning the origins of language, implying that human ancestors once had no language, have been frequent throughout history. In modern Western Philosophy, speculation by authors such as [[Thomas Hobbes]], and later [[Jean Jacques Rousseau]] lead to the [[Académie Francaise]] even declaring the subject off bounds. |

|||

The subject is of such interest to philosophy because language is such an essential characteristic of humans. In [[Ancient Philosophy|Classical Greek Philosophy]] such questions were connected to the subject of the Natures of things, in this case "[[Human Nature]]". Therefore already in Aristotle we see language being mentioned in discussions of natural propensities of humans to be political and to dwell in city state types of communities<ref>Politics 1253a 1.2</ref>, pair-bonding<ref>Nicomachean Ethics, VIII.12.1162a</ref>, poetical and so on. |

|||

Hobbes followed by [[John Locke]] and others claimed that language is an extension of the "speech" which humans have with themselves, which in a sense takes the classical view that reason is one of the most primary characteristics in humans. Others have argued the opposite - that reason developed out of the need for more complex communication. Rousseau, despite writing<ref>Second Discourse</ref> before the publication of [[Charles Darwin|Darwin]]'s [[Theory of Evolution]], shockingly claimed that there had once been humans who had no language or reason and who developed language first, rather than reason. |

|||

Since Darwin the subject has come to be treated more often than not by scientists rather than philosophers. For example neurologist [[Terrence Deacon]], has argued that reason and language "[[co-evolution|co-evolved]]". [[Merlin Donald]] sees language as a later development building up what he refers to as [[mimesis|mimetic]] [[culture]]<ref>[http://psycserver.psyc.queensu.ca/donaldm/reprints/evolutionaryOrigins18.pdf Evolutionary Origins of the Social Brain. In O. Vilarroya, & F.F i Argimon, (Eds.) Social Brain Matters: Stances on the Neurobiology of Social Cognition. Rodopi, 2007, 18: 215-222]</ref>, emphasizing that this co-evolution depended upon the interactions of many individuals. He writes that: |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

A shared communicative culture, with sharing of mental representations to some degree, must have come first, before language, creating a social environment in which language would have been useful and adaptive.<ref>[http://psycserver.psyc.queensu.ca/donaldm/reprints/PerspectivesImitation2.pdf Imitation and Mimesis. In S. Hurley, & N. Chater, (Eds.) Perspectives on Imitation: From Neuroscience to Social Science, Volume 2: Imitation, Human Development, and Culture. MIT Press, 2005, 14:282-300.]</ref> |

|||

</blockquote> |

|||

The specific causes of the natural selection that led to language are however still the subject of much speculation, but a common theme which goes right back to Aristotle is that many theories propose that the gains to be had from language and/or reason were probably mainly in the area of increasingly sophisticated social structures. |

|||

==The study of language== |

|||

===Linguistics=== |

|||

{{main|Linguistics}} |

|||

[[Linguistics]] is the [[science|scientific]] study of language, encompassing a number of sub-fields. At the core of [[theoretical linguistics]] are the study of language structure ([[grammar]]) and the study of meaning ([[semantics]]). The first of these encompasses [[morphology (linguistics)|morphology]] (the formation and composition of [[word]]s), [[syntax]] (the rules that determine how words combine into [[phrase]]s and [[Sentence (linguistics)|sentences]]) and [[phonology]] (the study of sound systems and abstract sound units). [[Phonetics]] is a related branch of linguistics concerned with the actual properties of speech sounds ([[phone]]s), non-speech sounds, and how they are produced and [[speech perception|perceived]]. |

|||

[[Theoretical linguistics]] is mostly concerned with developing models of linguistic knowledge. The fields that are generally considered as the core of theoretical linguistics are [[syntax]], [[phonology]], [[Morphology (linguistics)|morphology]], and [[semantics]]. [[Applied linguistics]] attempts to put linguistic theories into practice through areas like [[translation]], [[Stylistics (linguistics)|stylistics]], [[literary criticism]] and [[Literary theory|theory]], [[discourse analysis]], [[speech therapy]], speech pathology and [[Second language acquisition|foreign language teaching]]. |

|||

===History=== |

|||

{{main|History of linguistics}} |

|||

The historical record of [[linguistics]] begins in [[India]] with [[Pāṇini]], the 5th century BCE grammarian who formulated 3,959 rules of [[Sanskrit language|Sanskrit]] [[morphology (linguistics)|morphology]], known as the ''{{IAST|[[Aṣṭādhyāyī]]}}'' (अष्टाध्यायी) and with [[Tolkāppiyar]], the 3rd century BCE grammarian of the [[Tamil language|Tamil]] work [[Tolkāppiyam]]. {{Unicode|Pāṇini’s}} grammar is highly systematized and technical. Inherent in its analytic approach are the concepts of the [[phoneme]], the [[morpheme]], and the [[Root (linguistics)|root]]; Western linguists only recognized the phoneme some two millennia later. Tolkāppiyar's work is perhaps the first to describe [[articulatory phonetics]] for a language. Its classification of the alphabet into [[consonant]]s and [[vowel]]s, and elements like nouns, verbs, vowels, and consonants, which he put into classes, were also breakthroughs at the time. |

|||

In the [[Middle East]], the [[Persian Empire|Persian]] linguist [[Sibawayh]] (سیبویه) made a detailed and professional description of [[Arabic language|Arabic]] in 760 CE in his monumental work, ''Al-kitab fi al-nahw'' (الكتاب في النحو, ''The Book on Grammar''), bringing many [[Linguistics|linguistic]] aspects of language to light. In his book, he distinguished [[phonetics]] from [[phonology]]. |

|||

Later in the West, the success of [[science]], [[mathematics]], and other [[formal system]]s in the 20th century led many to attempt a formalization of the study of language as a "semantic code". This resulted in the [[academic discipline]] of [[linguistics]], the founding of which is attributed to [[Ferdinand de Saussure]].{{Fact|date=June 2007}} <!-- |

|||

Where do Wittgenstein and Quine argue this? [[Philosopher]]s such as [[Ludwig Wittgenstein]], [[W. V. Quine]], and [[Jacques Derrida]] have disputed the possibility of such a rigorous study of language by questioning many of the assumptions necessary for such a study, and have put forth their own views on the nature of language. There is no end in sight to this debate..--> In the 20th century, substantial contributions to the understanding of language came from [[Ferdinand de Saussure]], [[Hjelmslev]], [[Émile Benveniste]] and [[Roman Jakobson]],<ref name="Holquist81">Holquist 1981, xvii-xviii</ref> which are characterized as being highly [[systematic]].<ref name="Holquist81" /> |

|||

== Human languages == |

|||

{{main|Natural language}} |

|||

[[Image:Brain Surface Gyri.SVG|thumb|Some of the areas of the brain involved in language processing: |

|||

[[Broca's area]](Blue), [[Wernicke's area]](Green), [[Supramarginal gyrus]](Yellow), [[Angular gyrus]](Orange) ,[[Primary Auditory Cortex]](Pink)]] |

|||

Human languages are usually referred to as natural languages, and the science of studying them falls under the purview of [[linguistics]]. A common progression for natural languages is that they are considered to be first spoken, then written, and then an understanding and explanation of their grammar is attempted. |

|||

Languages live, die, move from place to place, and change with time. Any language that ceases to change or develop is categorized as a [[dead language]]. Conversely, any language that is in a continuous state of change is known as a ''living language'' or [[modern language]]. |

|||

Making a principled distinction between one language and another is usually impossible.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia| title =Language| encyclopedia =The New Encyclopædia Britannica: MACROPÆDIA |

|||

| volume =22| pages =548 2b| publisher =Encyclopædia Britannica,Inc.| date =2005}}</ref> For instance, there are a few [[dialect]]s of [[German language|German]] similar to some dialects of [[Dutch language|Dutch]]. The transition between languages within the same [[language family]] is sometimes gradual (see [[dialect continuum]]). |

|||

Some like to make parallels with [[biology]], where it is not possible to make a well-defined distinction between one species and the next. In either case, the ultimate difficulty may stem from the [[interaction]]s between languages and [[population]]s. (See [[Dialect]] or [[August Schleicher]] for a longer discussion.) |

|||

The concepts of [[Ausbausprache - Abstandsprache - Dachsprache|Ausbausprache, Abstandsprache and Dachsprache]] are used to make finer distinctions about the degrees of difference between languages or dialects. |

|||

==Artificial languages== |

|||

=== Constructed languages === |

|||

{{main|Constructed language}} |

|||

Some individuals and groups have constructed their own artificial languages, for practical, experimental, personal, or ideological reasons. International auxiliary languages are generally constructed languages that strive to be easier to learn than natural languages; other constructed languages strive to be more logical ("loglangs") than natural languages; a prominent example of this is [[Lojban]]. |

|||

Some writers, such as [[J. R. R. Tolkien]], have created fantasy languages, for literary, [[Artistic language|artistic]] or personal reasons. The fantasy language of the [[Klingon]] race has in recent years been developed by fans of the Star Trek series, including a vocabulary and grammar. |

|||

Constructed languages are not necessarily restricted to the properties shared by natural languages. |

|||

This part of ISO 639 also includes identifiers that denote constructed (or artificial) languages. In order to qualify for inclusion the language must have a literature and it must be designed for the purpose of human communication. Specifically excluded are reconstructed languages and computer programming languages. |

|||

===International auxiliary languages=== |

|||

{{main|International auxiliary language}} |

|||

Some languages, most constructed, are meant specifically for communication between people of different nationalities or language groups as an easy-to-learn second language. Several of these languages have been constructed by individuals or groups. Natural, pre-existing languages may also be used in this way - their developers merely catalogued and standardized their vocabulary and identified their grammatical rules. These languages are called ''naturalistic.'' One such language, [[Latino Sine Flexione]], is a simplified form of Latin. Two others, [[Occidental language|Occidental]] and [[Novial]], were drawn from several Western languages. |

|||

To date, the most successful auxiliary language is [[Esperanto]], invented by Polish ophthalmologist [[L. L. Zamenhof|Zamenhof]]. It has a relatively large community roughly estimated at about 2 million speakers worldwide, with a large body of literature, songs, and is the only known constructed language to have [[Native Esperanto speakers|native speakers]], such as the Hungarian-born American businessman [[George Soros]]. Other auxiliary languages with a relatively large number of speakers and literature are [[Interlingua]] and [[Ido]]. |

|||

===Controlled languages=== |

|||

{{main|Controlled natural language}} |

|||

Controlled natural languages are subsets of natural languages whose grammars and dictionaries have been restricted in order to reduce or eliminate both ambiguity and complexity. The purpose behind the development and implementation of a controlled natural language typically is to aid non-native speakers of a natural language in understanding it, or to ease computer processing of a natural language. An example of a widely used controlled natural language is [[Simplified English]], which was originally developed for [[aerospace]] industry maintenance manuals. |

|||

== Formal languages == |

|||

{{main|Formal language}} |

|||

[[Mathematics]] and [[computer science]] use artificial entities called formal languages (including [[programming language]]s and [[markup language]]s, and some that are more theoretical in nature). These often take the form of [[character string]]s, produced by a combination of [[formal grammar]] and semantics of arbitrary complexity. |

|||

=== Programming languages === |

|||

{{main|Programming language}} |

|||

A programming language is an extreme case of a formal language that can be used to control the behavior of a machine, particularly a computer, to perform specific tasks.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.webopedia.com/TERM/P/programming_language.html|publisher=Webopedia|accessdate=2007-11-23|title=What is programming language?}}</ref> Programming languages are defined using syntactic and semantic rules, to determine structure and meaning respectively. |

|||

Programming languages are used to facilitate communication about the task of organizing and manipulating information, and to express algorithms precisely. Some authors restrict the term "programming language" to those languages that can express all possible algorithms; sometimes the term "computer language" is used for artificial languages that are more limited. |

|||

== Animal communication == |

|||

{{main|Animal language}} |

|||

The term "[[animal language]]s" is often used for non-human languages. Linguists do not consider these to be "language", but describe them as [[animal communication]], because the interaction between animals in such communication is fundamentally different in its underlying principles from human language. Nevertheless, some scholars have tried to disprove this mainstream premise through experiments on training chimpanzees to talk. [[Karl von Frisch]] received the Nobel Prize in 1973 for his proof of the language and dialects of the bees.<ref>Frisch, K.v. (1953). 'Sprache' oder 'Kommunikation' der Bienen? Psychologische Rundschau 4. Amsterdam.</ref> |

|||

In several publicized instances, non-human animals have been taught to understand certain features of human language. [[Chimpanzee]]s, [[gorilla]]s, and [[orangutan]]s have been taught hand signs based on [[American Sign Language]]. The [[African Grey Parrot]], which possesses the ability to mimic human speech with a high degree of accuracy, is suspected of having sufficient intelligence to comprehend some of the speech it mimics. Most species of [[parrot]], despite expert mimicry, are believed to have no linguistic comprehension at all. |

|||

While proponents of animal communication systems have debated levels of [[semantics]], these systems have not been found to have anything approaching human language [[syntax]]. |

|||

== See also == |

|||

{{col-begin}} |

|||

{{col-2}} |

|||

*[[Adamic language]] |

|||

*[[Proto-language]] |

|||

*[[Dialect]] |

|||

*[[Extinct language]] |

|||

*[[FOXP2]] - gene implicated in cases of specific language impairment (SLI) |

|||

*[[Great ape language]] |

|||

*[[ISO 639]] - 2- and 3-letter ID codes for languages |

|||

*[[Language education]] |

|||

*[[Language policy]] |

|||

*[[Language reform]] |

|||

*[[Language school]] |

|||

*[[Linguistic protectionism]] |

|||

*[[Metacommunicative competence]] |

|||

*[[Non-verbal communication]] |

|||

*[[Official language]] |

|||

*[[Philology]] |

|||

*[[Philosophy of language]] |

|||

*[[Phonetic transcription]] |

|||

*[[Sapir–Whorf hypothesis]] |

|||

*[[Second language]] |

|||

*[[Symbolic communication]] |

|||

{{col-2}} |

|||

*[[Symbolic linguistic representation]] |

|||

*[[Translation]] |

|||

*[[Universal grammar]] |

|||

*[[Whistled language]] |

|||

*[[Word game]] |

|||

*[[Written language]] |

|||

===Lists=== |

|||

{{sisterlinks|commons=Atlas of languages|wikt=language|v=School:Language and Literature}} |

|||

*[[:Category:Lists of languages]] |

|||

*[[Ethnologue]] - list of languages, locations, population and genetic affiliation |

|||

*[[List of basic linguistics topics]] |

|||

*[[List of language academies]] |

|||

*[[List of languages]] |

|||

*[[List of official languages]] |

|||

{{col-end}} |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{portal}} |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

* [[Byomkes Chakrabarti|Chakrabarti, Byomkes]] (1994). ''A comparative study of Santali and Bengali''. Calcutta: K.P. Bagchi & Co. ISBN 8170741289 |

|||

* Crystal, David (1997). ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language.'' Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. |

|||

* Crystal, David (2001). ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language.'' Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. |

|||

* Gode, Alexander (1951). ''[[Interlingua-English Dictionary]].'' New York, Frederick Ungar Publishing Company. |

|||

*Holquist, Michael. (1981) [http://www.utexas.edu/utpress/excerpts/exbakdia.html#ex1 Introduction] to [[Mikhail Bakhtin]]'s ''The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays''. Austin and London: University of Texas Press. xv-xxxiv |

|||

* [[Eric R. Kandel|Kandel ER]], Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. ''[[Principles of Neural Science]]'', fourth edition, 1173 pages. McGraw-Hill, New York (2000). ISBN 0-8385-7701-6 |

|||

* Katzner, K. (1999). ''The Languages of the World.'' New York, Routledge. |

|||

* McArthur, T. (1996). ''The Concise Companion to the English Language.'' Oxford, Oxford University Press. |

|||

== Further reading == |

|||

*{{cite book |author=Deacon, Terrence William |title=The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Brain |publisher=W. W. Norton & Company |location=New York |year=1998 |pages= |isbn=0-393-31754-4 |oclc= |doi= |accessdate=}} |

|||

*{{cite book |author=Polinsky, Maria; Comrie, Bernard; Matthews, Stephen |title=The atlas of languages: the origin and development of languages throughout the world |publisher=Facts on File |location=New York |year=2003 |pages= |isbn=0-8160-5123-2 |oclc= |doi= |accessdate=}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Spoken Wikipedia|Language.ogg|2005-07-19}} |

|||

*[http://www.netz-tipp.de/languages.html Distribution of languages on the Internet (2002)] |

|||

*[http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats7.htm Top Languages in the world Internet usage population and penetration report (Nov 2007)] |

|||

*[http://www.goethe.de/lhr/prj/mac/enindex.htm The impact of language in a globalised world - Goethe-Institut] |

|||

*[http://wals.info/index World Atlas of Language Structures] |

|||

[[Category:Languages|Languages]] |

|||

[[Category:Language|Language]] |

|||

[[Category:Linguistics|Linguistics]] |

|||

[[Category:Human communication]] |

|||

[[Category:Human skills]] |

|||

[[af:Taal]] |

|||

[[als:Sprache]] |

|||

[[ar:لغة]] |

|||

[[an:Luengache]] |

|||

[[frp:Lengua]] |

|||

[[ast:Idioma]] |

|||

[[gn:Ñe'ẽ]] |

|||

[[ay:Aru]] |

|||

[[az:Dil]] |

|||

[[bm:Kan]] |

|||

[[bn:ভাষা]] |

|||

[[zh-min-nan:Gí-giân]] |

|||

[[map-bms:Basa]] |

|||

[[ba:Тел (фән)]] |

|||

[[be:Мова]] |

|||

[[be-x-old:Мова]] |

|||

[[bar:Sprache]] |

|||

[[br:Yezh]] |

|||

[[bg:Език (лингвистика)]] |

|||

[[ca:Llenguatge]] |

|||

[[cv:Чĕлхе]] |

|||

[[ceb:Pinulongan]] |

|||

[[cs:Jazyk (lingvistika)]] |

|||

[[cy:Iaith]] |

|||

[[da:Sprog]] |

|||

[[pdc:Schprooch]] |

|||

[[de:Sprache]] |

|||

[[dv:ބަސް]] |

|||

[[nv:Bizaad]] |

|||

[[et:Keel (keeleteadus)]] |

|||

[[el:Γλώσσα]] |

|||

[[es:Lenguaje]] |

|||

[[eo:Lingvo]] |

|||

[[eu:Hizkuntza]] |

|||

[[fa:زبان]] |

|||

[[fr:Langage]] |

|||

[[fy:Taal]] |

|||

[[fur:Lengaç]] |

|||

[[ga:Teanga (cumarsáid)]] |

|||

[[gd:Cànan]] |

|||

[[gl:Linguaxe]] |

|||

[[gu:ભાષા]] |

|||

[[ko:언어]] |

|||

[[hi:भाषा]] |

|||

[[hr:Jezik]] |

|||

[[io:Linguo]] |

|||

[[ilo:Pagsasao]] |

|||

[[id:Bahasa]] |

|||

[[ia:Linguage]] |

|||

[[xh:Ulwimi]] |

|||

[[is:Tungumál]] |

|||

[[it:Linguaggio]] |

|||

[[he:שפה]] |

|||

[[jv:Basa]] |

|||

[[ka:ენა (მეტყველება)]] |

|||

[[kw:Yeth]] |

|||

[[ky:Тил]] |

|||

[[sw:Lugha]] |

|||

[[kg:Ndinga]] |

|||

[[ht:Lang]] |

|||

[[ku:Ziman]] |

|||

[[la:Lingua]] |

|||

[[lv:Valoda]] |

|||

[[lb:Sprooch]] |

|||

[[lt:Kalba]] |

|||

[[li:Taol]] |

|||

[[ln:Lokótá]] |

|||

[[jbo:bangu]] |

|||

[[hu:Nyelv]] |

|||

[[mk:Јазик]] |

|||

[[mg:Fiteny]] |

|||

[[ml:ഭാഷ]] |

|||

[[mr:भाषा]] |

|||

[[mzn:Zivan]] |

|||

[[ms:Bahasa]] |

|||

[[cdo:Ngṳ̄-ngiòng]] |

|||

[[nl:Taal]] |

|||

[[ja:言語]] |

|||

[[ce:Мотт]] |

|||

[[no:Språk]] |

|||

[[nn:Språk]] |

|||

[[nrm:Laungue]] |

|||

[[oc:Lenga]] |

|||

[[ps:ژبه]] |

|||

[[pl:Język (mowa)]] |

|||

[[pt:Linguagem]] |

|||

[[ksh:Sprooch]] |

|||

[[ro:Limbă]] |

|||

[[rmy:Chhib]] |

|||

[[qu:Rimay]] |

|||

[[ru:Язык]] |

|||

[[se:Giella]] |

|||

[[sc:Limbas]] |

|||

[[sco:Leid]] |

|||

[[stq:Sproake]] |

|||

[[scn:Lingua (parràta)]] |

|||

[[simple:Language]] |

|||

[[sk:Jazyk (lingvistika)]] |

|||

[[sl:Jezik (sredstvo sporazumevanja)]] |

|||

[[sr:Језик]] |

|||

[[fi:Kieli]] |

|||

[[sv:Språk]] |

|||

[[tl:Wika]] |

|||

[[ta:மொழி]] |

|||

[[th:ภาษา]] |

|||

[[vi:Ngôn ngữ]] |

|||

[[tg:Забон (суxан)]] |

|||

[[tr:Dil (lisan)]] |

|||

[[tk:Dil]] |

|||

[[uk:Мова]] |

|||

[[vo:Pük]] |

|||

[[fiu-vro:Keeleq]] |

|||

[[wa:Lingaedje]] |

|||

[[yi:שפראך]] |

|||

[[zh-yue:語言]] |

|||

[[diq:Zıwan (lisan)]] |

|||

[[bat-smg:Kalba]] |

|||

[[zh:语言]] |

|||

Revision as of 16:21, 13 October 2008

A language is a dynamic set of visual, auditory, or tactile symbols of communication and the elements used to manipulate them. Language can also refer to the use of such systems as a general phenomenon. Language is considered to be an exclusively human mode of communication; although other animals make use of quite sophisticated communicative systems, none of these are known to make use of all of the properties that linguists use to define language.

In Western Philosophy, language has long been closely associated with reason, which is also a uniquely human way of using symbols. In Ancient Greek philosophical terminology, the same word, logos, was used as a term for both language or speech and reason, and the philosopher Thomas Hobbes used the English word "speech" so that it similarly could refer to reason, as will be discussed below. More commonly though, the English word "language", derived ultimately from lingua, Latin for tongue, typically refers only to expressions of reason which can be understood by other people, most obviously by speaking.

Properties of language

A set of commonly accepted symbols is only one feature of language; all languages must define the structural relationships between these symbols in a system of grammar. Rules of grammar are what distinguish language from other forms of communication. They allow a finite set of symbols to be manipulated to create a potentially infinite number of grammatical utterances.

Another property of language is that its symbols are arbitrary. Any concept or grammatical rule can be mapped onto a symbol. Most languages make use of sound, but the combinations of sounds used do not have any inherent meaning – they are merely an agreed-upon convention to represent a certain thing by users of that language. For instance, there is nothing about the Spanish word nada itself that forces Spanish speakers to convey the idea of "nothing". Another set of sounds (for example, the English word nothing) could equally be used to represent the same concept, but all Spanish speakers have acquired or learned to correlate this meaning for this particular sound pattern. For Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian or Bosnian speakers on the other hand, nada means something else; it means "hope".

This arbitrariness does not, however, apply to words with an onomatopoetic dimension (i.e. words that to some extent simulate the sound of the token referred to). For example, the bird cuckoo's name was indeed not given arbitrarily.

Origins of language

Even before the Theory of Evolution made discussion of more animal-like human ancestors common place, philosophical and scientific speculation concerning the origins of language, implying that human ancestors once had no language, have been frequent throughout history. In modern Western Philosophy, speculation by authors such as Thomas Hobbes, and later Jean Jacques Rousseau lead to the Académie Francaise even declaring the subject off bounds.

The subject is of such interest to philosophy because language is such an essential characteristic of humans. In Classical Greek Philosophy such questions were connected to the subject of the Natures of things, in this case "Human Nature". Therefore already in Aristotle we see language being mentioned in discussions of natural propensities of humans to be political and to dwell in city state types of communities[1], pair-bonding[2], poetical and so on.

Hobbes followed by John Locke and others claimed that language is an extension of the "speech" which humans have with themselves, which in a sense takes the classical view that reason is one of the most primary characteristics in humans. Others have argued the opposite - that reason developed out of the need for more complex communication. Rousseau, despite writing[3] before the publication of Darwin's Theory of Evolution, shockingly claimed that there had once been humans who had no language or reason and who developed language first, rather than reason.

Since Darwin the subject has come to be treated more often than not by scientists rather than philosophers. For example neurologist Terrence Deacon, has argued that reason and language "co-evolved". Merlin Donald sees language as a later development building up what he refers to as mimetic culture[4], emphasizing that this co-evolution depended upon the interactions of many individuals. He writes that:

A shared communicative culture, with sharing of mental representations to some degree, must have come first, before language, creating a social environment in which language would have been useful and adaptive.[5]

The specific causes of the natural selection that led to language are however still the subject of much speculation, but a common theme which goes right back to Aristotle is that many theories propose that the gains to be had from language and/or reason were probably mainly in the area of increasingly sophisticated social structures.

The study of language

Linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of language, encompassing a number of sub-fields. At the core of theoretical linguistics are the study of language structure (grammar) and the study of meaning (semantics). The first of these encompasses morphology (the formation and composition of words), syntax (the rules that determine how words combine into phrases and sentences) and phonology (the study of sound systems and abstract sound units). Phonetics is a related branch of linguistics concerned with the actual properties of speech sounds (phones), non-speech sounds, and how they are produced and perceived.

Theoretical linguistics is mostly concerned with developing models of linguistic knowledge. The fields that are generally considered as the core of theoretical linguistics are syntax, phonology, morphology, and semantics. Applied linguistics attempts to put linguistic theories into practice through areas like translation, stylistics, literary criticism and theory, discourse analysis, speech therapy, speech pathology and foreign language teaching.

History

The historical record of linguistics begins in India with Pāṇini, the 5th century BCE grammarian who formulated 3,959 rules of Sanskrit morphology, known as the Aṣṭādhyāyī (अष्टाध्यायी) and with Tolkāppiyar, the 3rd century BCE grammarian of the Tamil work Tolkāppiyam. Pāṇini’s grammar is highly systematized and technical. Inherent in its analytic approach are the concepts of the phoneme, the morpheme, and the root; Western linguists only recognized the phoneme some two millennia later. Tolkāppiyar's work is perhaps the first to describe articulatory phonetics for a language. Its classification of the alphabet into consonants and vowels, and elements like nouns, verbs, vowels, and consonants, which he put into classes, were also breakthroughs at the time. In the Middle East, the Persian linguist Sibawayh (سیبویه) made a detailed and professional description of Arabic in 760 CE in his monumental work, Al-kitab fi al-nahw (الكتاب في النحو, The Book on Grammar), bringing many linguistic aspects of language to light. In his book, he distinguished phonetics from phonology.

Later in the West, the success of science, mathematics, and other formal systems in the 20th century led many to attempt a formalization of the study of language as a "semantic code". This resulted in the academic discipline of linguistics, the founding of which is attributed to Ferdinand de Saussure.[citation needed] In the 20th century, substantial contributions to the understanding of language came from Ferdinand de Saussure, Hjelmslev, Émile Benveniste and Roman Jakobson,[6] which are characterized as being highly systematic.[6]

Human languages

Human languages are usually referred to as natural languages, and the science of studying them falls under the purview of linguistics. A common progression for natural languages is that they are considered to be first spoken, then written, and then an understanding and explanation of their grammar is attempted.

Languages live, die, move from place to place, and change with time. Any language that ceases to change or develop is categorized as a dead language. Conversely, any language that is in a continuous state of change is known as a living language or modern language.

Making a principled distinction between one language and another is usually impossible.[7] For instance, there are a few dialects of German similar to some dialects of Dutch. The transition between languages within the same language family is sometimes gradual (see dialect continuum).

Some like to make parallels with biology, where it is not possible to make a well-defined distinction between one species and the next. In either case, the ultimate difficulty may stem from the interactions between languages and populations. (See Dialect or August Schleicher for a longer discussion.)

The concepts of Ausbausprache, Abstandsprache and Dachsprache are used to make finer distinctions about the degrees of difference between languages or dialects.

Artificial languages

Constructed languages

Some individuals and groups have constructed their own artificial languages, for practical, experimental, personal, or ideological reasons. International auxiliary languages are generally constructed languages that strive to be easier to learn than natural languages; other constructed languages strive to be more logical ("loglangs") than natural languages; a prominent example of this is Lojban.

Some writers, such as J. R. R. Tolkien, have created fantasy languages, for literary, artistic or personal reasons. The fantasy language of the Klingon race has in recent years been developed by fans of the Star Trek series, including a vocabulary and grammar.

Constructed languages are not necessarily restricted to the properties shared by natural languages.

This part of ISO 639 also includes identifiers that denote constructed (or artificial) languages. In order to qualify for inclusion the language must have a literature and it must be designed for the purpose of human communication. Specifically excluded are reconstructed languages and computer programming languages.

International auxiliary languages

Some languages, most constructed, are meant specifically for communication between people of different nationalities or language groups as an easy-to-learn second language. Several of these languages have been constructed by individuals or groups. Natural, pre-existing languages may also be used in this way - their developers merely catalogued and standardized their vocabulary and identified their grammatical rules. These languages are called naturalistic. One such language, Latino Sine Flexione, is a simplified form of Latin. Two others, Occidental and Novial, were drawn from several Western languages.

To date, the most successful auxiliary language is Esperanto, invented by Polish ophthalmologist Zamenhof. It has a relatively large community roughly estimated at about 2 million speakers worldwide, with a large body of literature, songs, and is the only known constructed language to have native speakers, such as the Hungarian-born American businessman George Soros. Other auxiliary languages with a relatively large number of speakers and literature are Interlingua and Ido.

Controlled languages

Controlled natural languages are subsets of natural languages whose grammars and dictionaries have been restricted in order to reduce or eliminate both ambiguity and complexity. The purpose behind the development and implementation of a controlled natural language typically is to aid non-native speakers of a natural language in understanding it, or to ease computer processing of a natural language. An example of a widely used controlled natural language is Simplified English, which was originally developed for aerospace industry maintenance manuals.

Formal languages

Mathematics and computer science use artificial entities called formal languages (including programming languages and markup languages, and some that are more theoretical in nature). These often take the form of character strings, produced by a combination of formal grammar and semantics of arbitrary complexity.

Programming languages

A programming language is an extreme case of a formal language that can be used to control the behavior of a machine, particularly a computer, to perform specific tasks.[8] Programming languages are defined using syntactic and semantic rules, to determine structure and meaning respectively.

Programming languages are used to facilitate communication about the task of organizing and manipulating information, and to express algorithms precisely. Some authors restrict the term "programming language" to those languages that can express all possible algorithms; sometimes the term "computer language" is used for artificial languages that are more limited.

Animal communication

The term "animal languages" is often used for non-human languages. Linguists do not consider these to be "language", but describe them as animal communication, because the interaction between animals in such communication is fundamentally different in its underlying principles from human language. Nevertheless, some scholars have tried to disprove this mainstream premise through experiments on training chimpanzees to talk. Karl von Frisch received the Nobel Prize in 1973 for his proof of the language and dialects of the bees.[9]

In several publicized instances, non-human animals have been taught to understand certain features of human language. Chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans have been taught hand signs based on American Sign Language. The African Grey Parrot, which possesses the ability to mimic human speech with a high degree of accuracy, is suspected of having sufficient intelligence to comprehend some of the speech it mimics. Most species of parrot, despite expert mimicry, are believed to have no linguistic comprehension at all.

While proponents of animal communication systems have debated levels of semantics, these systems have not been found to have anything approaching human language syntax.

See also

|

Lists

|

Notes

- ^ Politics 1253a 1.2

- ^ Nicomachean Ethics, VIII.12.1162a

- ^ Second Discourse

- ^ Evolutionary Origins of the Social Brain. In O. Vilarroya, & F.F i Argimon, (Eds.) Social Brain Matters: Stances on the Neurobiology of Social Cognition. Rodopi, 2007, 18: 215-222

- ^ Imitation and Mimesis. In S. Hurley, & N. Chater, (Eds.) Perspectives on Imitation: From Neuroscience to Social Science, Volume 2: Imitation, Human Development, and Culture. MIT Press, 2005, 14:282-300.

- ^ a b Holquist 1981, xvii-xviii

- ^ "Language". The New Encyclopædia Britannica: MACROPÆDIA. Vol. 22. Encyclopædia Britannica,Inc. 2005. pp. 548 2b.

- ^ "What is programming language?". Webopedia. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ Frisch, K.v. (1953). 'Sprache' oder 'Kommunikation' der Bienen? Psychologische Rundschau 4. Amsterdam.

References

- Chakrabarti, Byomkes (1994). A comparative study of Santali and Bengali. Calcutta: K.P. Bagchi & Co. ISBN 8170741289

- Crystal, David (1997). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Crystal, David (2001). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Gode, Alexander (1951). Interlingua-English Dictionary. New York, Frederick Ungar Publishing Company.

- Holquist, Michael. (1981) Introduction to Mikhail Bakhtin's The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin and London: University of Texas Press. xv-xxxiv

- Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of Neural Science, fourth edition, 1173 pages. McGraw-Hill, New York (2000). ISBN 0-8385-7701-6

- Katzner, K. (1999). The Languages of the World. New York, Routledge.

- McArthur, T. (1996). The Concise Companion to the English Language. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- Deacon, Terrence William (1998). The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Brain. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31754-4.

- Polinsky, Maria; Comrie, Bernard; Matthews, Stephen (2003). The atlas of languages: the origin and development of languages throughout the world. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-5123-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)