Marine debris: Difference between revisions

m →Law of Europe: my typo |

→Law of Europe: logical punctuation |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

===Law of Europe=== |

===Law of Europe=== |

||

In 1972 and 1974, conventions were held in [[Oslo]] and [[Paris]] respectively, and resulted in the passing of the [[Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic|OSPAR Convention]], an international treaty controlling marine pollution in the north-east [[Atlantic Ocean]] around Europe.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ospar.org/eng/html/welcome.html |title=The OSPAR Convention |accessdate=2008-05-29 |publisher=OSPAR Commission }}</ref> The [[Water Framework Directive]] of 2000 is a [[Directive (European Union)|European Union directive]] committing [[Member State of the European Union|EU member states]] to make their inland and coastal waters free from human influence.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32000L0060:EN:HTML| title=Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy |accessdate=2008-05-29 |publisher=EurLex }}</ref> In the United Kingdom, the proposed [[Marine Bill]] is designed to "ensure clean healthy, safe, productive and biologically diverse oceans and seas, by putting in place better systems for delivering sustainable development of marine and coastal environment |

In 1972 and 1974, conventions were held in [[Oslo]] and [[Paris]] respectively, and resulted in the passing of the [[Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic|OSPAR Convention]], an international treaty controlling marine pollution in the north-east [[Atlantic Ocean]] around Europe.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ospar.org/eng/html/welcome.html |title=The OSPAR Convention |accessdate=2008-05-29 |publisher=OSPAR Commission }}</ref> The [[Water Framework Directive]] of 2000 is a [[Directive (European Union)|European Union directive]] committing [[Member State of the European Union|EU member states]] to make their inland and coastal waters free from human influence.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32000L0060:EN:HTML| title=Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy |accessdate=2008-05-29 |publisher=EurLex }}</ref> In the United Kingdom, the proposed [[Marine Bill]] is designed to "ensure clean healthy, safe, productive and biologically diverse oceans and seas, by putting in place better systems for delivering sustainable development of marine and coastal environment".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.defra.gov.uk/marine/legislation/index.htm | title=Marine Bill |accessdate=2008-07-29 |publisher=UK Defra }}</ref> |

||

[[Image:No Dumping Drains to Stream by David Shankbone.jpg|thumb|A spray-painted sign above a sewer in [[Colorado Springs, Colorado|Colorado Springs]] warning people to not pollute the local stream by [[Environmental dumping|dumping]]]] |

[[Image:No Dumping Drains to Stream by David Shankbone.jpg|thumb|A spray-painted sign above a sewer in [[Colorado Springs, Colorado|Colorado Springs]] warning people to not pollute the local stream by [[Environmental dumping|dumping]]]] |

||

Revision as of 21:18, 10 August 2008

Marine debris, also known as marine litter, is human-created waste that has deliberately or accidentally become afloat in a lake, sea, ocean or waterway. Oceanic debris tends to accumulate at the centre of gyres and on coastlines,[1] frequently washing aground where it is known as beach litter.

Some forms of marine debris, such as harmless driftwood, occur naturally, and human activities have been adding similar material into the oceans for thousands of years. Recently, however, with the advent of plastic, has human influence become an issue as many types of plastics do not biodegrade.

A type of marine pollution, waterborne plastic is both unsightly and dangerous; posing a serious threat to fish, seabirds, marine reptiles, and marine mammals, as well as to boats and coastal habitations.[2] Ocean dumping, accidental container spillages, and wind-blown landfill waste are all contributing to this growing problem.

Types of debris

A wide variety of anthropogenic artefacts can become marine debris; plastic bags, buoys, rope, medical waste, glass bottles and plastic bottles, cigarette lighters, beverage cans, styrofoam, lost fishing line and nets, and various wastes from cruise ships and oil rigs are among the items commonly found to have washed ashore. Six pack rings, in particular, are considered a poster child of the damage that garbage can do to the marine environment.

Eighty percent of all known debris is plastic – a component that has been rapidly accumulating since the end of World War II.[3] Plastics accumulate because they don't biodegrade as many other substances do; although they will photodegrade on exposure to sunlight, they do so only under dry conditions, as water inhibits this process.[4]

Ghost nets

Fishing nets left or lost in the ocean by fishermen – known as 'ghost nets' – can entangle fish, dolphins, sea turtles, sharks, dugongs, crocodiles, seabirds, crabs, and other creatures. Acting as designed, these nets restrict movement, causing starvation, laceration and infection, and, in those that need to return to the surface to breath, suffocation.[5]

Nurdles and plastics bags

Nurdles, also known as mermaids' tears, are plastic pellets typically under five millimetres in diameter, and are a major contributor to marine debris. They are used as a raw material in plastics manufacturing, and are thought to enter the natural environment after accidental spillages. Mermaids' tears are also created through the physical weathering of larger plastic debris. Nurdles strongly resemble fish eggs, only instead of finding a nutritious meal, any marine wildlife that ingests them will likely starve, be poisoned and die.[6]

Plastic shopping bags act similarly in that they also clog digestive tracts when consumed.[7] Plastic bags can cause starvation through restricting the movement of food, or by filling the stomach and tricking the animal into thinking it is full. A 1994 study of the seabed using trawl nets in the North-Western Mediterranean around the coasts of Spain, France and Italy reported a particularly high mean concentration of debris; an average of 1935 items per square kilometre. 77% of the debris was plastics and of this, 93% were plastic bags.[7]

Source of debris

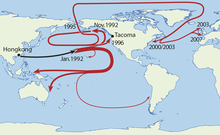

It has been estimated that container ships lose over 10,000 containers at sea each year (usually during a storm).[8] One famous spillage occurred in the Pacific Ocean in 1992, when thousands of rubber ducks and other toys went overboard during a storm. The toys have since been found all over the world; Curtis Ebbesmeyer and other scientists have used the incident to gain a better understanding of ocean currents. Similar incidents have happened before, with the same potential to track currents, such as when Hansa Carrier dropped 21 containers (with one notably containing buoyant Nike shoes).[9] In 2007, MSC Napoli was beached in the English Channel, and dropped hundreds of containers, most of which washed up on the Jurassic Coast, a World Heritage Site.[10]

Though it was originally assumed that most oceanic marine waste stemmed directly from ocean dumping, it is now thought that around four fifths[11] of the oceanic debris is from rubbish blown seaward from landfills, and urban runoff washed down storm drains.[2] In the 1987 Syringe Tide, medical wastes washed ashore in New Jersey after having been blown from the Fresh Kills Landfill.[12][13]

Legality of ocean and river dumping

Ocean dumping is the deliberate disposal of wastes at sea, a practice controlled by international law:

- The London Convention (1972) – a United Nations agreement to control ocean dumping[14]

- MARPOL 73/78 – an international convention designed to minimise pollution of the seas, including dumping, oil and exhaust pollution[15]

Law of Europe

In 1972 and 1974, conventions were held in Oslo and Paris respectively, and resulted in the passing of the OSPAR Convention, an international treaty controlling marine pollution in the north-east Atlantic Ocean around Europe.[16] The Water Framework Directive of 2000 is a European Union directive committing EU member states to make their inland and coastal waters free from human influence.[17] In the United Kingdom, the proposed Marine Bill is designed to "ensure clean healthy, safe, productive and biologically diverse oceans and seas, by putting in place better systems for delivering sustainable development of marine and coastal environment".[18]

Law of the United States

In 1972, the United States Congress passed the Ocean Dumping Act, giving the Environmental Protection Agency power to monitor and regulate the dumping of sewage sludge, industrial waste, radioactive waste and biohazardous materials into the nation's territorial waters.[19] The Act was amended sixteen years later to also include medical wastes.[20] Currently, the California State Legislature is considering a host of bills designed to reduce the sources of marine debris, following the recommendations of the California Ocean Protection Council.[21]

Ownership of debris

Lost, mislaid, and abandoned property can be of consequence within property law, admiralty law, and the law of the sea. Salvage law has as a basis that a salvor should be rewarded for risking his life and property to rescue the property of another from peril. On land the distinction between deliberate and accidental loss led to the concept of a 'treasure trove'. In the United Kingdom, shipwrecked goods should be reported to a Receiver of Wreck, and if identifiable, they should be returned to their rightful owner.[22]

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Once waterbourne, debris is far from immobile. Flotsam can be blown by the wind, and follows the flow of ocean currents, often ending up in the middle of oceanic gyres where currents are weakest. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is one such example of this, comprising of a vast region of the North Pacific Ocean rich with anthropogenic wastes. Conservative estimates of its size compare it to Texas,[23] whereas some reckon it closer to the size of Africa.[24] The mass of plastic in our oceans may be as high as one hundred million tonnes.[11]

Should any islands be unlucky enough to lie within a gyre, their coastlines will likely be ruined by the waste that inevitably washes ashore. Prime examples of this are Midway[25] and Hawaii.[26] Clean-up teams around the world patrol beaches to clean up this environmental threat.[25]

Environmental impact

Many animals that live on or in the sea consume flotsam by mistake, as it often looks similar to their natural prey.[27] Plastic debris, when bulky or tangled, is difficult to pass, and may become permanently lodged in the digestive tracts of these animals, blocking the passage of food and causing death through starvation or infection.[28] Tiny floating particles also resemble zooplankton, which can lead filter feeders to consume them and cause them to enter the ocean food chain. In samples taken from the North Pacific Gyre in 1999 by the Algalita Marine Research Foundation, the mass of plastic exceeded that of zooplankton by a factor of six.[3][29] More recently, reports have surfaced that there may now be 30 times more plastic than plankton, the most abundant form of life in the ocean.[30]

Toxic additives used in the manufacture of plastic materials can leech out into their surroundings when exposed to water. Waterborne hydrophobic pollutants collect and magnify on the surface of plastic debris,[11] thus making plastic far more deadly in the ocean than it would be on land.[3] Hydrophobic contaminants are also known to bioaccumulate in fatty tissues, biomagnifying up the food chain and putting great pressure on apex predators. Some plastic additives are known to disrupt the endocrine system when consumed, others can suppress the immune system or decrease reproductive rates.[29]

However, not all anthropogenic artefacts in the oceans do harm. Iron and concrete do little damage to the environment as they are generally immobile; in fact, they can even be used as scaffolding for the creation of artificial reefs, increasing the biodiversity of a coastal region. Entire ships have been deliberately sunk in coastal waters with that purpose in mind.[31] Some organisms have adapted to live on mobile plastic debris[32] and this has had the unfortunate consequence of allowing the inhabitants to disperse all over the world, becoming invasive species in remote ecosystems.[33]

References

- ^ Gary Strieker (28 July 1998). "Pollution invades small Pacific island". CNN. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Facts about marine debris". US NOAA. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ a b c Alan Weisman (2007). The World Without Us. St. Martin's Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 0312347294.

- ^ Alan Weisman (Summer 2007). "Polymers Are Forever". Orion magazine. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ "'Ghost fishing' killing seabirds". BBC News. 28 June 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Plastics 'poisoning world's seas'". BBC News. 7 December 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Marine Litter: An analytical overview" (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. 2005. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Janice Podsada (19 June 2001). "Lost Sea Cargo: Beach Bounty or Junk?". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Marsha Walton (28 May 2003). "How sneakers, toys and hockey gear help ocean science". CNN. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Scavengers take washed-up goods". BBC News. 22 January 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c "Plastic Debris: from Rivers to Sea" (PDF). Algalita Marine Research Foundation. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ Alfonso Narvaez (8 December 1987). "New York City to Pay Jersey Town $1 Million Over Shore Pollution". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "A Summary of the Proposed Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan". New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary Program. February 1995. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ "London Convention". US EPA. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ "International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 relating thereto (MARPOL 73/78)". International Maritime Organization. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ "The OSPAR Convention". OSPAR Commission. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ "Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy". EurLex. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ "Marine Bill". UK Defra. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ "Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972" (PDF). US Senate. 29 December 2000. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Ocean Dumping Ban Act of 1988". US EPA. 21 November 1988. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Stopping the Rising Tide of Marine Debris Pollution". Californians Against Waste. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ^ "Can you keep ship-wrecked goods?". BBC News. 22 January 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The trash vortex". Greenpeace. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ Charles Moore (2002-10-02). "Great Pacific Garbage Patch". Santa Barbara News-Press.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "New 'battle of Midway' over plastic". BBC News. 26 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Plastic blights Hawaii's beaches". BBC News. 11 June 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kenneth R. Weiss (2 August 2006). "Plague of Plastic Chokes the Seas". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Charles Moore (November 2003). "Across the Pacific Ocean, plastics, plastics, everywhere". Natural History. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ^ a b "Plastics and Marine Debris". Algalita Marine Research Foundation. 2006. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ "Learn". NoNurdles.com. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ^ "Chapter 5: Reefing" (PDF). Disposal Options for Ships. Rand Corporation. 2 August 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ocean Debris: Habitat for Some, Havoc for Environment, Experts Say". National Geographic. 23 April 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Rubbish menaces Antarctic species". BBC News. 24 April 2002. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

External links

- NOAA Marine Debris Program – US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Marine Debris Abatement – US Environmental Protection Agency

- Marine Research, Education and Restoration – Algalita Marine Research Foundation

- Beach Litter – UK Marine Conservation Society

- Harmful Marine Debris – Australian Government

- The trash vortex – Greenpeace

- High Seas GhostNet Survey – US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Rubber Duckies Map The World – CBS News

- Social & Economic Costs of Marine Debris – US NOAA Socioeconomics