Tunisian campaign

| Tunisia Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||

November 23, 1942. The crew of an M3 (Lee) tank from the U.S. 1st Armored Division at Souk el Arba, Tunisia. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The Tunisia Campaign (also known as the Battle of Tunisia) was a series of World War II battles that took place in Tunisia in the North African Campaign of World War II, between forces of the German/Italian Axis, and allied forces consisting primarily of U.S., British and former Vichy French. The battle opened with initial success by the German forces, but the massive supply and numerical superiority of the Allies eventually led to the Germans' complete defeat. Over 275,000 German and Italian troops were taken as prisoners of war, including most of the Deutsches Afrika Korps (DAK).

Background

The early portions of the war in North Africa was marked primarily by a lack of supplies and the inability to provide any sort of concentrated logistics support. The British supply head at Alexandria and the Italian bases at Benghazi and Tobruk were separated by over 400 miles (650 km) of land that was generally passable only along a narrow corridor along the coast. At the time the central Mediterranean was contested, and although the British would normally enjoy military superiority over the Italians, their ability to supply their garrison via Alexandria was limited both by Italian actions as well as pressing needs in other theaters.

The limited supplies led to a "back and forth" contest for the land along the coast. The initial Italian offensive drove almost 1000 miles to the Egyptian border, but by that point their supplies were almost gone as they had little logistical ability at the best of times. The British, still close to their supply bases, quickly built up their own forces and counterattacked well into Libya. With the arrival of the Germans the front moved eastward, once again petering out as the Germans outran their lines of supply.

But things had changed dramatically by 1942. By this point the Royal Navy had finally driven the Italian fleet out of the Mediterranean and allowed British transports free movement, while the British retention of Malta allowed the Royal Air Force to interdict an increasing amount of Italian supplies at sea. Now the supply situation increasingly swung to the British favor, eventually becoming overwhelming.

With the German retreat following Bernard Montgomery's breakout in Egypt following the Second Battle of El Alamein in November 1942, and with Montgomery's 8th Army no longer short of supplies as in early battles, it would only be a matter of time before the British arrived in Libya. Only days later on November 8th, Operation Torch landed additional allied forces to the west, potentially trapping the Axis forces between the two allied groups in Libya's poor defensive terrain.

Much better defensive possibilities existed to the west, in Tunisia. Tunisia is roughly rectangular, with its eastern border defined by the Gulf of Sidra and north by the Mediterranean. Most of the inland western border with Algeria was astride the western line of the roughly triangular Atlas Mountains. This portion of the border was easily defendable in the limited number of passes through the two north-south lines of the mountains. In the south a second line of lower mountains limited the approaches to a narrow area between these Matmata Hills and the coast. The French had earlier constructed a 20 km wide and 30 km deep series of strong defensive works known as the Mareth Line along this plain, in order to defend against an Italian invasion from Libya. Only in the north was the terrain favorable to attack; here the Atlas Mountains stopped near the eastern coast, leaving a large area on the northwest coast unprotected.

Generally, Tunisia offered an excellent and fairly easily defended base of operations. Defensive lines in the north could deal with the approaching Allied forces of Operation Torch, while the Mareth Line made the south rather formidable. In between, there were only a few easily defended passes though the Atlas Mountains. Better yet, Tunisia offered two major deepwater ports at Tunis and Bizerte, only a few hundred miles from Italian supply bases on Sicily. Supplies could be brought in at night, protecting them from the RAF's patrols, stay during the day, and the return again the next night. In contrast, Italy to Libya was a full-day trip, making supply operations rather dangerous.

In Hitler's view, Tunisia could hold out for months, or years, upsetting Allied plans in Europe.

Axis buildup

The elements of the Operation Torch forces which had landed at Algiers, known as the Eastern Task Force, had originally planned on following their landings with Commando and Airborne attacks into Tunisia. These plans were upset when the local Vichy commanders entered into lengthy negotiations on whether or not to support the Allies, forcing the Allies to leave large garrison forces spread throughout the Vichy territories of northwest Africa. Although this allowed forward bases to be constructed and supplies to be moved forward, no offensive action was taken. A quick run into Tunisia would have been possible had it been carried out immediately, but it wasn't, and Eisenhower would later write that the American operations violated every recognized principle of war.

Tunisian officials were undecided about whom to support, and they did not close access to their airfields to either side. As early as November 10 the Italian Air Force sent a flight of 28 fighters to Tunis. Two days later an airlift began that would bring in over 15,000 men and 581 tons of supplies. By the end of the month they had shipped in three German divisions, including the 10th Panzer Division, and two Italian infantry divisions. On November 12th, Walther Nehring was assigned command of the newly formed XC Corps, and flew in on November 17.

The run for Tunis

Eventually, on November 22, the North African Agreement finally placed the Vichy on the allied side, allowing the Allied garrison troops to be sent forward to the front. By this time the Axis had been able to build up an entire Corps, and the German forces outnumbered their Allied counterparts in almost all ways.

The two forces met for the first time at Djebel Abiod on the 17th, the same day Nehring arrived. He ordered a spoiling retreat; the Eastern Task Force followed, reaching Sidi Nsir on the 18th, Medjez el Bab on 19th-20th, and near el Aroussa on the 23rd.

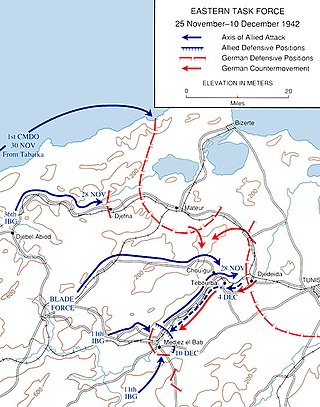

The first true Allied offensive started on November 25, 1942. Their plan was to break through the Axis lines, then separate and take Bizerte and Tunis. Once Bizerte was taken Torch would come to an end. Attacking in the north towards Bizerte would be British 36th Infantry Brigade and in the south British 11th Infantry Brigade, both part of Major General Vivian Evelegh's British 78th Infantry Division. Between the two infantry thrusts would be 78th Division's "Blade Force", an armoured regimental group commanded by Colonel Richard Hull which included tanks, motorised infantry, paratroops, artillery, anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns and engineers[1].

The first encounters happened that day, and again Nehring ordered spoiling attacks, and withdrew from Majaz al Bab (shown on Allied maps as Medjez el Bab or just Medjez) that night along the road to Tebourba. The Luftwaffe, happy to have local air superiority whilst the Allies planes had to fly from relatively distant bases in Algeria, caused serious havoc among the columns moving eastward over the next two days. Nevertheless, part of Blade Force comprising 17 light M3 tanks of Company C, 1st Battalion, 1st Armored Regiment, U.S. 1st Armored Division under the command of Major Rudolph Barlow infiltrated behind German lines to the newly activated airbase at Djedeida in the afternoon. In a lightning attack, the tanks destroyed more than 20 enemy aircraft on the ground, while shooting up several buildings, supply dumps, and killing and wounding a number of the defenders. Company C lost one tank, and several crewmen before withdrawing to their own lines.

The Eastern Task Force fought steadily northeast against the delaying actions of the retreating Axis forces, while Nehring and his XC Corps set up a new defensive line behind Tebourba at Djedeida, only 30 km from Tunis. The Allied forces met them on November 27 and were sent reeling back with 30 men killed, and 86 prisoners of war. A second attempt was made in the early hours of 28 November with the help of armor from U.S. 1st Armored Division's Combat Command 'B', and they quickly lost five tanks to anti-tank guns positioned within the town[2].

On December 1 the Axis forces mounted a counterattack. Over the next four days they managed to push the Allies back to their starting points on the high ground on each side of the river west of Terbourba[3]. Finally as Allied troops built up in Tunisia a new H.Q. under 1st Army was activated, that of British V Corps under Lieutenant-General Charles Allfrey, to take over command of all forces in the Tebourba sector. Despite Anderson's wish to make one more attempt to break through to Tunis, Allfrey considered the weakened units facing Tebourba were highly threatened and ordered a retreat of roughly 6 miles to the high positions of Longstop Hill and Bou Aoukaz on each side of the river. On the 10 December German tanks attacked Combat Command B on Bou Aoukaz becoming hopelessly bogged down in the mud. In turn, the U.S. tanks counter-attacked and were also mired and picked off , losing 18 tanks[4]. Allfrey was still concerned over the vulnerability of his force and ordered a further withdrawal west so that by the end of 10 December Allied units held a defensive line just east of Medjez el Bab. This string of Allied defeats in December cost them dearly; over men 1,000 missing (prisoners of war), 73 tanks, 432 other vehicles, and 70 artillery pieces lost.

The Allies started a buildup for another attack, and were ready by late December, 1942. The continued but slow buildup had brought Allied force levels up to a total of 20,000 British, 11,800 American, and 7,000 French troops. A hasty intelligence review showed about 25,000 combat and 10,000 service troops, mostly German, in front of them.

On the night of December 16-December 17, a company of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division made a successful raid on Maknassy, 155 miles (250 km) south of Tunis, and took twenty-one Italian prisoners. The main attack began the afternoon of December 22, despite rain and insufficient air cover, elements of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division's 18th Regimental Combat team and 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards of 78th Division's Guards Infantry Brigade made progress up the lower ridges of the 900-foot (270 m) Longstop Hill that controlled the river corridor from Medjez to Tebourba and thence to Tunis. By the morning of 23 December the Coldstreams had driven back the elements of German 10th Panzer Division on the summit were then relieved by 18 RCT and were withdrawn to Mejdez. The Germans regained the hill in a counter-attack and the Coldstreams were ordered back to Longstop. The next day they had regained the peak and with 18 RCT dug in. However, by 25 December, with ammunition running low and Axis forces now holding adjacent high ground, the Longstop position became untenable and the Allies were forced to withdraw to Medjez[5] and by 26 December 1942, the Allies had withdrawn to the line they had set out from two weeks earlier, having suffered 534 casualties.

The Allied run for Tunis had been stopped.

Stalemate

While the battles wound down, factionalism among the French again erupted. On 24 December François Darlan was assassinated for his collaboration with the Nazis, and Henri Giraud was selected as replacement by the United States. Charles de Gaulle was somewhat upset that he was not chosen. Nevertheless, he had hated Darlan, considering him a traitor to France and was happy to see him go.

To the frustration of the Free French the US government had so far had displayed considerable willingness to make a deal with Darlan and the Vichyists. Consequently Darlan’s disappearance was of great benefit to them. Under the joint chairmanship of the Giraud and de Gaulle the CFLN, the Committee for French National Liberation, was formed. de Gaulle quickly eclipsed Giraud, who more or less willingly from then on deferred to the Leader of the Free French.

Things were similarly upsetting for the Germans. Nehring, considered by most to be an excellent commander, had continually infuriated his superiors with his outspoken critiques. Over the winter they decided to "replace" him by upgrading the forces to full strength under General Hans-Jürgen von Arnim's Fifth Panzer Army. The Army consisted of the composite heavy infantry unit Division von Broich (later Division von Manteuffel) in the Bizerte area, the 10th Panzer Division in the center before Tunis, and the Italian Superga Division on the southern flank. From mid-November through January, 112,000 men and 101,000 tons of supplies and equipment arrived in Tunisia, something that the Allies found terribly frustrating given their overwhelming naval superiority.

Eisenhower, meanwhile, transferred remaining units from Morocco and Algeria eastward into Tunisia. In the north, Lt Gen Kenneth Anderson's Eastern Task Force was upgraded to the British First Army with four corps under command: three more divisions, 1st, 4th and 46th, forming British IX Corps soon joined the 6th Armoured and 78th Infantry Divisions of V Corps already in Tunisia. In the south, the basis of a two-division French corps (French XIX Corps) was being built. In the center was a new U.S. II Corps, to be commanded by Lloyd Fredendall, eventually consisting of the majority of six divisions: the 1st, 3rd, 9th, and 34th Infantry and the 1st and 2nd Armored.

The U.S. also started to build up a complex of logistics bases in Algeria and Tunisia, with the eventual goal of forming a large forward base at Maknassy, on the eastern edge of the Atlas Mountains, in excellent position to cut off Rommel's forces approaching from the south.

Rommel pushes back in the center to Kasserine

Erwin Rommel, meanwhile, had made plans to retreat to the Mareth Line as soon as the British 8th Army finally caught up. This would leave the Axis forces in control of the two natural entrances into Tunisia in the north and south, with only the easily defended mountain passes between them. On January 23, 1943 the 8th Army took Tripoli, by which point Rommel was already well on his way west.

By this point in time, elements of the U.S. forces had crossed into Tunisa through passes in the Atlas Mountains from Algeria, controlling the interior of the triangle formed by the mountains. Their position had the potential of cutting the DAK off from von Antrim's forces to the north. Rommel could not let this stand, and formed a plan to attack these forces before they could form much of a threat.

On January 30, 1943, the German 21st Panzer met elements of the French forces near Faïd, the main pass from the eastern arm of the mountains into the coastal plains. They rolled over them, surrounding two U.S. battalions near them that had been positioned too far apart for mutual support. Several counterattacks were organized, including a number by the U.S. 1st Armored Division, but all of these were beaten off with ease. After three days the U.S. gave up, and the lines were withdrawn into the interior plains and made a new forward defensive line at the small town of Sbeitla.

The Germans started forward once again the next week to take Sbeitla. The U.S. forces held for two days, but eventually the defense started to collapse on the night of February 16, 1943, and the town lay empty by midday on the 17th (see also the Battle of Sidi Bou Zid). This left the entirety of the interior plains in German hands, and the remaining Allied forces retreated further, back to the two passes on the western arm of the mountains into Algeria, at Sbiba and Kasserine.

At this point there was some argument in the German camp about what to do next; all of Tunisia was under Axis control, and there was little to do until the 8th Army caught up. Their offensive stopped even as the U.S. forces retreated in disarray. The 8th continued to dither, and eventually Rommel decided his next course of action was to simply take the U.S. supplies on the Algerian side of the western arm of the mountains. Although doing little for his own situation, it would seriously upset any possible US actions from that direction.

On February 19, 1943, Rommel launched what would become the Battle of the Kasserine Pass. After two days of rolling over the U.S. defenders, the Afrika Korps had suffered few casualties, while the U.S. forces lost 6000 men and two-thirds of their tanks. On the night of February 21st, 1943, British troops, elements of 6th Armoured and 46th Infantry Divisions, arrived to bolster the U.S. defense, having been pulled from the British lines facing the Germans in Sbiba. Nevertheless, the following day opened with yet another German thrashing of the Americans until the arrival of four U.S. artillery battalions made offensive operations difficult.

Faced with stiffening defenses and the alarming news that the British 8th Army's lead elements had finally reached Medenine, only a few kilometers from the German-held Mareth Line, Rommel decided to call off the attack and return to the lines on the night of the February 22nd, 1943, hoping that the attack had caused enough damage to upset any actions from the north over the next little while. Rommel's forces reached the western end of the line on the 25th, but the British had been on the eastern end since the 17th and launched probes westward on the 26th. On March 6th, 1943, the majority of Rommel's forces, three German armored divisions, two light divisions, and elements of three Italian divisions, launched Operation Capri, an attack southward in the direction of Medenine, the northernmost British strong point. British artillery fire was intense, beating off the Axis attack and knocking out 55 of the remaining 150 Axis tanks.

Action then abated for a time, and both sides studied the results of recent battles. Rommel remained convinced that the U.S. forces posed little threat, while the British were his equal. He held this opinion for far too long, and it would prove very costly in the future. The US likewise studied the battle, and relieved several senior commanders while issuing several "lessons learned" publications to improve future performance. Most important, on March 6, 1943, command of the U.S. II Corps passed from Fredendall to George Patton, with Omar N. Bradley as assistant Corps Commander. Commanders were reminded that large units should be kept concentrated to ensure mass on the battlefield, rather than widely dispersed as Fredendall had deployed them. This had the intended side effect of improving the fire control of the already-strong US artillery. Close air support had also been weak, and while improvements were made, a truly satisfactory solution was not arrived upon until the Battle of Normandy.

Montgomery breaks the Mareth Line

Montgomery launched his major attack, Operation Pugilist, against the Mareth Line in the night of 19 March/20 March 1943. Elements of the British 50th Infantry Division penetrated the line and established a bridgehead west of Zarat on 20 March/21 March, but a determined counterattack by 15th Panzer Division destroyed the pocket and established the line once again during 22 March.

On 26 March, General Horrocks' X Corps drove around the Matmata Hills, captured the Tebaga Gap and capturing the town of El Hamma at the northern extreme of the line (Operation Supercharge II). This flanking movement made most of the Mareth Line untenable. The following day, German and Italian units managed to stop Horrock's advance with well-placed anti-tank guns, in an attempt to gain time for a strategic withdrawal. Within 48 hours the defenders of the Mareth Line marched 60 kilometers northwest and established new defensive positions at Wadi Akarit near Gabes.

With the best defensive works now in British hands, and no sign that the 8th Army was slowing down, Rommel returned to Germany to attempt to convince Hitler to abandon Tunisia and return the Afrika Korps to Europe. Hitler refused, and Rommel was placed on sick leave.

Gabes

By this point the newly reorganized U.S. II Corp had started out of the passes again, and were in position to the rear of the German lines. The 10th Panzer was tasked with pushing them back into the interior, and the two forces met at Battle of El Guettar on 23 March. At first the battle went much as it had in earlier matchups, with the German tanks rolling up lead units of the US forces. However, they soon ran into a US minefield, and immediately the US artillery and anti-tank units opened up on them. The 10th lost 30 tanks over a short period, and retreated out of the minefield. A second attack formed up in the late afternoon, this time supported by infantry, but this attack was also beaten off and the 10th returned to Gabes.

The US was unable to take advantage of the German failure, however, and spent several frustrating weeks attempting to push Italian infantry off two strategic hills on the road to Gabes. Repeated major attempts would make progress, only to be pushed back by small units of the 10th or 21st Panzer who would drive up the road from Gabes in an hour or so. Better air support would have made this "mobile defense" difficult, but coordination between air and ground forces remained a serious problem for the Allies.

Both the 8th Army and the U.S. II Corps continued their attacks over the next week, and eventually the 8th broke the lines and the DAK was forced to abandon Gabes and retreat to join the other Axis forces far to the north. The hills in front of the US forces were abandoned, allowing them to join the British forces in Gabes later that day. From this point on the battle was one of attrition.

Endgame

By this stage, Allied aircraft had been moved forward to airfields in Tunisia, and large numbers of German transport aircraft were shot down between Sicily and Tunis. British destroyers operating from Malta prevented reinforcement or evacuation of Tunisia by sea. Admiral Cunningham, Eisenhower's Naval Task Force commander, issued Nelsonian orders to his ships: "Sink, burn, capture, destroy. Let nothing pass".

The final drive to clear Tunisia began on April 19. By this time the German-Italian forces had been pushed into a defensive line on the north-east coast of Tunis, attempting to protect their supply lines, but with little hope of continuing the battle for long. The Allied forces had re-formed. The U.S. II Corps was transferred to the north of the line, and began attacking towards Bizerta. The British First Army (consisting of V Corps and IX Corps) attacked towards Tunis, in the centre. The French XIX Corps held the sector around Pont du Fahs. The British Eighth Army made some attacks north of Enfidaville on the Mediterranean coast, but it became clear that this sector was too strongly held for any breakthrough to occur, and several of Eighth Army's divisions were transferred to the main attack in the centre.

With the Allies still preparing their next move, the Germans tested the British center in an attack by the Hermann Goering Division the night of 20 April-21 April. Though they penetrated up to five miles at some points, they could not force a general withdrawal, and eventually returned to their lines. On the 22nd the V Corps' 46th Infantry Division struck back; losses were high on both sides but the British inched ahead, capturing, at the start of May, the vital "Longstop Hill" which commanded the road between Medjez el Bab and Tebourba. The next day the entire Allied front attacked.

The final assault was launched on May 6 by British IX Corps, now commanded by Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks after its first commander was injured. Two infantry and two armoured divisions concentrated on a narrow front and broke through. On May 7 British armor entered Tunis, and American infantry entered Bizerte. Six days later the last Axis resistance in Africa ended with the surrender of over 275,000 prisoners of war, many of them newly arrived from Sicily and more needed there. The Axis's desperate gamble had only slowed the inevitable by perhaps a season, and the US loss at Kasserine may have been the best thing that could have happened to them.

With North Africa now in Allied hands, plans quickly turned to the invasion of Sicily, and Italy after it.

See Also

References

- Charles R. Anderson. Online Bookshelves WWII Campaigns: Tunisia 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. US Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-12.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - US Army Center of Military History Online Bookshelves: To Bizerte with the II Corps 23 April to 13 May 1943. Historical Division, War Department (for the American Forces in Action series). 1943. CMH Pub 100-6.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - Gregory Blaxland (1977.). The Plain Cook and the Great Showman. ISBN 0-7183-0185-4.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Ken Ford (1999). Battleaxe Division. ISBN 0-7509-1893-4.