Patriarchy

Patriarchy describes the structuring of society on the basis of family units, where fathers have primary responsibility for the welfare of their families. In some cultures, slaves were included as part of such households. The word patriarchy is often used, by extension, to refer to the expectation that men also take primary responsibility for the welfare of the community as a whole, and hence fulfil the duties of public office (in anthropology and feminism, for example).

The feminine form of patriarchy is matriarchy, but there are no known examples of matriarchy.[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] Encyclopædia Britannica says it is a "hypothetical social system".[7] The Britannica article goes on to note, "The view of matriarchy as constituting a stage of cultural development is now generally discredited. Furthermore, the consensus among modern anthropologists and sociologists is that a strictly matriarchal society never existed."[8] For more information see the appendix Patriarchies in dispute.

Margaret Mead (a very famous anthropologist) boldy said, "All the claims so glibly made about societies ruled by women are nonsense. We have no reason to believe that they ever existed. ... men everywhere have been in charge of running the show. ... men have been the leaders in public affairs and the final authorities at home."[9] For moral comment on this see Feminist criticism below; for a scientific explanation of why see Biology of gender below.

Etymology

The word patriarchy comes from two Greek words – patēr (πατήρ, father) and archē (αρχή, rule). In Greek, the genitive form of patēr is patr-os,[10] which shows the root form patr, explaining why the word is spelled patr-iarchy. The letter i in patr-i-archy occurs, because patēr comes into English via Latin, which had a different vowel flavour to Greek in the genitive (pater/patris), for example the abbreviation DVP stands for Decessit Vita Patris (literally, she died in the life of the father). The basic meaning of the Greek word archē is actually "beginning" (hence arche-ology)[11] – the first words of Genesis in Greek (see Septuagint) are En archē ("In the beginning").[12] However, archē is also used metaphorically to refer to ruling, because rulers are perceived to "start" things.[13] This use of archē is especially common in compound words, for example hier-archy and an-archy.

Related words

A patriarch is a man who has great influence on his family or society. Some historical societies claimed descent from one great man. For example, the Romans believed they were descended from Romulus who founded Rome. The traditional founder of Athens is Erectheus, and of Sparta Lacedæmon. Similarly, the Jewish tradition in the Torah says Jews are descended from Abraham through Isaac. Both the Torah and Qur'an say Arabs are descended from Abraham through Ishmael,[14] [15] Abraham's first son, Isaac's half-brother. Traditional founders are often called patriarchs. The feminine form of patriarch is matriarch, for example see Matriarchs (Bible). Patriarch is also a name for the most senior leaders of Eastern Christianity, roughly comparable to the western arch-bishop (archē again).

The adjective for patriarchy is patriarchal; and patriarchalism or, more commonly, paternalism refer to the practice or defence of patriarchy. Patron is a related word used generically (that is, it is not gender or sex specific). Women and men who provide financial support to activities within a community can be termed patrons. The verb form patronize can be used positively, to describe the activity of patrons, or negatively, to describe adopting a superior attitude. If the superior attitude is adopted by a man, he can be called paternalistic.

Related customs

Patrimonalism uses the Greek word monos (μόνος, sole) to describe the view of a state as the extended household of a mon-arch (sole ruler) or deity. We have records of patrimonalism almost as far back as the earliest writing itself (about 5000 years ago). In fact, this is probably because patrimonalism directly facilitated the invention of writing – the first hereditary monarchs gained so much wealth as to need to keep accounts, and enough to pay those accountants. The earliest records of patrimonalism come from Ancient Near Eastern legal documents, the best known being the Code of Hammurabi and the Torah. Some aspects of patrimonalism can still be found in the few remaining monarchies in the world today, for example, British law concerning real estate (see Crown lands), especially in Australia. For more detail regarding patrimonalism see Traditional authority.

Some social customs reflect what is termed patrilineality or patrilocality.

Patrilineal describes customs where family responsibilities and assets pass from father to son. By contrast, contemporary Judaism considers people to be Jewish if their mothers were Jewish, which makes this aspect of contemporary Judaism matrilineal. Biblical Judaism is, however, a classical example of a patriarchal society. Matrilineal is a particularly useful term in genetics, where some genetic features are exclusively passed via the maternal line. The mother's X chromosome is always passed to offspring, male and female. However, daughters do not receive a Y chromosome, and sons do not receive an X chromosome from their fathers (see Sex-determination system, Heredity and Genetic genealogy).

Patrilocal describes the custom of brides relocating to the geographic community of the husband and his father's family. In a matrilocal society, a husband will relocate to the home community of his wife and her mother (see also Marriage). Matrilocality can substantially increase the social influence of women in a culture, however, given that tribal and family leaders are still men in all known matrilocal societies, matrilocality is not equivalent to matriarchy, see main entry Patriarchy (anthropology).

By contrast with these other customs, patriarchy can be seen to be distinctly about gender and the nuclear family, gender and public office, and about female-male relationships in general.

Feminist criticism

Main entry: Patriarchy in feminism

Most forms of feminism have challenged patriarchy as a social system that is adopted uncritically, due to millennia of human experience where male physical strength was the ultimate way of settling social conflicts – from war to disciplining children. John Stuart Mill wrote, "In early times, the great majority of the male sex were slaves, as well as the whole of the female. And many ages elapsed ... before any thinker was bold enough to question the rightfulness, and the absolute necessity, either of the one slavery or of the other."[16]

During the democratic and anti-slavery movements of early 19th century Europe and America, kingdoms became constitutional monarchies or republics and slavery was made illegal (see abolitionism). The civil rights movements of 20th century America also sought to overthrow various existing social structures, that were seen by many to be oppressive and corrupt. Both social contexts led naturally to an analogous scrutiny of relationships between women and men (see Mill above). The 19th century debate ultimately resulted in women receiving the vote; this is sometimes referred to as first-wave feminism. The late 20th century debate has produced far ranging social restructuring in Western democracies – second-wave feminism. Although often credited with it, Simone de Beauvoir denied she started second wave feminism, "The current feminist movement, which really started about five or six years ago [1970-71], did not really know [The Second Sex]".[17] Some consider the "second wave" to be continuing into the 21st century, others consider it to be complete, still others consider there to be a "third wave" of feminism active in contemporary society.

The opposite of feminism is not masculism but patriarchy. It is not surprising, therefore, that the word patriarchy has a range of additional, negative associations when used in the context of feminist theory, where it is sometimes capitalized and used with the definite article (the Patriarchy), likely best understood as a form of collective personification (compare "blame it on the Government" to "blame it on the Patriarchy"). The use of the word patriarchy in feminist literature has been arguably overused as a rhetorical device (see Cathy Young and Misandry), becoming so loaded with emotive associations, that some writers prefer to use an approximate synonym, the more objective and technical androcentric (also from Greek – anēr, genitive andros, meaning man).

Fredrika Scarth (a feminist) reads Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex to be saying, "Neither men nor women live their bodies authentically under patriarchy."[18] Mary Daly wrote, "Males and males only are the originators, planners, controllers, and legitimators of patriarchy."[19] Carole Pateman, another feminist, writes, "The patriarchal construction of the difference between masculinity and femininity is the political difference between freedom and subjection."[20]

Most feminists do not propose to replace patriarchy with matriarchy, rather they argue for equality (though some have argued for separation). However, equality is a difficult idea (see Egalitarianism), "People who praise it or disparage it disagree about what they are praising or disparaging."[21] It is particularly hard to work out what equality means when it comes to gender, because there are real differences between men and women (see Sexual dimorphism and Gender differences). Recent feminist writers speak of "feminisms of diversity", that seek to reconcile older debates between equality feminisms and difference feminisms. For instance, Judith Squires writes, "The whole conceptual force of 'equality' rests on the assumption of differences, which should in some respect be valued equally."[22]

For a leading feminist who writes against patriarchy see Marilyn French; and for one who is more sympathetic see Christina Hoff Sommers.

In summary, recent feminist writers have shown a tendency to admit misandry among some members of the movement (for example Cathy Young above), and acknowledge real differences in men and women that make diversity a more meaningful aim than reductionistic equality (for example Judith Squires above). However, the basic issue stands out even more clearly now than at the peak of second wave activism in the early 1970s. Decades of legislation and affirmative action have not yet changed the fact that western culture is male dominated, it remains patriarchal. Women can vote in most countries of the world, and they outnumber men in higher education in many countries. However, heads of state, cabinet ministers and the top executives of major companies are still male dominated (see glass ceiling). Also, women's average income is still significantly lower than male average income.

If what so many people believe is true, that male domination and patriarchy are morally wrong and damage women, there is still a lot of work to do. Feminists are still doing both theoretical and practical work to change things, for what they believe to be the best for everyone; but one man predicted they would not (and will not) change male domination and patriarchy, see below.

Steven Goldberg

Steven Goldberg (born 1941) was chairman of the department of sociology at City College of New York. He is probably the only author to have written two whole books on patriarchy. In his second book on patriarchy he wrote:

There is nothing in this book concerned with the desirability or undesirability of the institutions whose universality the book attempts to explain. For instance, this book is not concerned with the question of whether male domination of heirarchies is morally or politically 'good' or 'bad'. Moral values and political policies, by their nature, consist of more than just empirical facts and their explanation. 'What is' can never entail 'what should be', so science knows nothing of 'should'. 'Answers' to questions of 'should' require subjective elements that science cannot provide. Similarly, there is no implication that one sex is 'superior' in general to the other; 'general superiority' and 'general inferiority' are scientifically meaningless concepts.[23]

His first book was published in 1973 – the early days of second wave feminist activism. Like feminists (and this article), he started with the data that all known societies have constructed patriarchies. This data requires both moral comment and scientific explanation. Consider the theory that "all power corrupts". If all known cases of people with power result in some form of corruption, we need to study both the moral question of eliminating corruption, and the scientific question of how power leads to corruption – perhaps a just society should eliminate power structures, perhaps it only needs to modify them. Another analogy is psychology, it seeks to identify both what constitutes a pathology and what causes it, in order to work out both what to treat and how. In the case of patriarchy, feminism largely provides moral comment, Goldberg tries to provide the scientific explanation. It is important to note that Goldberg's aim is neither to recommend nor to condemn patriarchy, he simply provides a hypothesis to explain it. It is also important to note that science is neither superior nor inferior to ethics. They advance human knowledge in different directions by asking different types of question. Ideally the two assist one another.

In Goldberg's first book, he seeks an explanation for three specific aspects of male dominance behaviour in human societies. Patriarchy is the first of these. He also considers the phenomenon of male status seeking, which he calls "male attainment". Finally, he considers the way men seem to dominate in one-to-one relationships with women. Marriage is just one example of such relationships. Goldberg comments, "A woman’s feeling that she must get around a man is the hallmark of male dominance."[24]

Goldberg proposes the hypothesis that the statistical averages of all these forms of behaviour are partly explained by the necessary (but not sufficient) condition of neuroendocrinological effects – namely, testosterone. The title of his first book makes his hypothesis very clear, it was called The Inevitability of Patriarchy: Why the Biological Difference between Men and Women always Produces Male Domination. At the time he wrote (1973), there were only very limited results from biological researchers to support his hypothesis. The situation has changed a lot since then.

Biology of gender

It has long been known that there are correlations between the biological sex of animals and their behaviour. It has also long been known that human behaviour is influenced by the brain.

This section will summarize sex research in humans, especially that related to the formation of gender identity, starting with John Money and Milton Diamond. It will also cover the effects on rats of sex hormone treatment, and the amazing results published in 2006–2007 concerning genetically programmed sexual dimorphism in rat brains, prior even to the influence of hormones on development.

Genes on the sex chromosomes can directly influence sexual dimorphism in cognition and behaviour, independent of the action of sex steroids.

Skuse, David H (2006). "Sexual dimorphism in cognition and behaviour: the role of

X-linked genes". European Journal of Endocrynology. 155: 99–106. {{cite journal}}: line feed character in |title= at position 58 (help)

Some specific relevant results are as follows. The brains of many animals, including humans, are significantly different for females and males of the species. Both genes and hormones affect the formation of many animal brains before "birth" (or hatching), and also behaviour of adult individuals. Hormones significantly affect human brain formation, and also brain development at puberty. Both kinds of brain difference affect male and female behaviour.

Brain differences also have a statistically measurable effect on an array of abilities. In particular, on average, women are more capable in nearly everything to do with sensory processing (a bit like comparing the red group to the purple group in the diagram). On the other hand, male brains seem to be "pushed" towards extremes of low ability or high ability in various forms of mental abstraction, especially those related to space and logic. This means the average scores of young women and men in mathematics, for example, will be close, but there will be more men than women in the very low scores and in the very high scores (like red and green, or red and blue). Hormones have also been linked with male aggression.

In short, science has caught up with what feminists, Goldberg and common sense have said for a long time – on average, men are more aggressive in social behaviour. This does not justify patriarchy, it merely partially explains it.

The explanation is only partial because there is a lot of variation in men and women that is not yet understood. It cannot be proven that female-ness or male-ness is 100% biological (in fact it almost certainly isn't), but what has been shown is that female-ness and male-ness are certainly not 100% determined by upbringing and culture. These things are an exciting area of future research, with profound relevance to people of many different types.

While this section is being composed, the interested reader may wish to consult some older, but now well-established, results.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2007) |

Research and ethics

One important thing to note about the biological research is that most of it was generally motivated by seeking the causes of diseases in human beings, and ways of treating or preventing those diseases. For example, there is study into genetic predisposition to, or causes of, Alzheimer's disease and mental illnesses. Also:

Scientists have cracked the code of an essential signal in the sequence of steps that controls the molecular choreography of gene regulation. The discovery is expected to aid development of therapies and prevention strategies for certain genetically triggered diseases such as breast cancers, pediatric cancers, and leukemia.

Kennedy, Barbara K (2001). "Key Step in Gene Activation Discovered". Science Journal. 18.

Research results are relevant to gender issues, but that is not their direct concern. Sexual dimorphism in the brain is important to study, because we may need to apply different kinds of treatment to women and to men. Injections for tetanus work the same for men and women, but involve biological intervention to promote health. Perhaps one day science may be able to tell us how we could stop patriarchy, by biological intervention; but science can't tell us if patriarchy is a kind of disease. This takes us back to the importance of the moral questions. For example: if an injection could remove male dominance behaviour, should it be made law for such an injection to be given? Should parents be given the choice? These are ethical questions normally thought to require informed debate. The text of this article has provided information from a number of sources, and recorded different positions offered in the debate so far. There are still many unknowns, but new research is being both conducted and published every year. More literature is provided below.

Patriarchies in dispute

The following is a list of patriarchal societies alleged by some to be matriarchal and, where available, quotes from the anthropologists who originally studied them. In nearly every case it is clear from what the women and men who studied them report, that the societies were patriarchal not matriarchal, even before changes brought by contact with western culture. What some of the societies do typify, however, is matrilinearity or matrilocality, not matriarchy, because of clear features of male dominance, see the main entry Patriarchy (anthropology). This is the evidence that verifies the statements made by Encyclopaedia Britannica, Margaret Mead, Cynthia Eller and Steven Goldberg elsewhere in this article, and has been mainly located using their bibliographies. There are a lot of cultural groups in this list. No bias is intended against the more than 1,000 uncontroversially patriarchal cultural groups, nor against the few matrilocal or matrilineal cultural groups not mentioned here. [Note: the social customs described in the list that follows are neither endorsed nor condemned by the anthropologists who report them, nor by those who cite them, nor by this article.]

Alorese (main entry Alor)

"Marriage means for women far greater economic responsibility in a social system that does not grant them status recognition equal to that of men while at the same time it places on them greater and more monotonous burdens of labor."

Bois, Cora du (1944). The People of Alor: A Social-Psychological Study of an East Indian Island. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bamenda (main entry Bamenda)

"Women are not eligble for the headship of kin or political groups."

Kaberry, Phyllis M (1952). Women of the Grassfields. London: Colonial Research Publications 14.

Bantoc

"As is typical of the Bantoc ... the Tanowong are organized into different dap-ay groups ... . The dap-ay ... is the men's house. The dap-ay are the religeous, social, and political centers of village life, where major decisions are made ... . While each dap-ay theoretically has a council of old men who make the decisions, in actual fact, especially at present, every mature man participates in the deliberations of the council."

Bacadayan, Albert S (1974). "Securing water for drying rice terraces: irrigation, community organization, and expanding social relationships in a Western Bontoc group, Philippines". Ethnology. 13: 247–260.

Batek (main entry Batek)

"Wives usually go where their husbands want to go and the men seem to prefer their own home areas. ... The Batek have a system of headmanship which appears to go back some time. There are at least seven men in the Aring and Lebir Valleys today who are commonly regarded as penghulu ('headmen') and they have in their genealogy several generations of penghulu, menteri ('ministers' or 'chiefs'), panglima ('war captains'), and even a raja ('king'). ... The position of the penghulu descends to the sons of previous penghulu, ideally in order of birth. If the penghulu has no sons, it goes to his next oldest brother and then to his sons in order."

Endicott, Kirk Michael (1974). Batek Negrito Economy and Social Organization. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Unpublished PhD thesis. pp. 239–246.

Boyowans (autonym, also known as people of Kiriwina or Trobriand Islanders)

These are matrilinear, patrilocal and patriarchal tribes. Maternal uncles are family heads, and the tribal chiefs are dynastic male monarchs, paid a tribute.

"A district is formed by a number of villages, which are tributary to a particular headman of high rank, a chief."

"A chief has a wife from each subject village."

"The headman of a village is the oldest male of the dominant subclan."

"Next to the chief and sorcerer, the garden magician is the most important person in the village. He may even be the chief. He is a hereditary specialist in a complex system of magic handed down in the female line."

"Fishermen are organized into detachments, each of which is led by a headman who owns the canoe, performs the magic, and reaps the main share of the catch."

"Although descent is matrilineal, postmarital residence is patrilocal."

Quotes from an article sourced on Malinowski (see below) by Martin J Malone.

Malinowski, Bronisław (1916). "Baloma: Spirits of the Dead in the Trobriand Islands". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 46: 354–430. Malinowski, Bronisław (1918). "Fishing in the Trobriand Islands". Man. 18: 87–92. Malinowski, Bronisław (1920). "Kula: The Circulating Exchange of Valuables in the Archipelagoes of Eastern New Guinea". Man. 20: 87–105. Malinowski, Bronisław (1920). "The Economic Pursuits of the Trobriand Islanders". Nature. 105: 564–565. Malinowski, Bronisław (1921). "The Primitive Economics of the Trobriand Islanders". The Economic Journal. 21: 1–16. Malinowski, Bronisław (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific. Seattle: Washington University Press. Malinowski, Bronisław (1936). "The Trobriand Islands of Papua". Australian Geographer. 3: 10–12.

There is an amusing anecdote of cross-cultural contact on Kiriwina. The local yam is part of the staple diet and has something of a contraceptive effect. The Kiriwina tribes were initially reluctant to believe western stories of sex causing pregnancy.

Bribri (main entry Bribri)

"(The brother) ... or in the default of a brother, a cousin or uncle, [has a ruling voice in any family council or discussion]."

Gabb, William Moore (1875). "On the Indian tribes and languages of Costa Rica". American Philosophical Society Proceedings. 14: 483–602.

Çatalhöyük (main entry Çatalhöyük)

"The archaeological evidence of female oriented ritual at Catal Hüyük is no more a substatial demonstration of matriarchy than some future excavations of a contemporary shrine of La Virgin de Guadalupe (or some other cult of the Madonna) might uncover."

Webster, Steven (1973). "Was it Matriarchy?". New York Review of Books: 37–38.

Chambri (main entry Chambri previously spelled Tchambuli)

"Nowhere [in Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies] do I suggest that I have found any material which disproves the existance of sex differences [in Tchambuli Society]. ... This study was not concerned with whether there are or are not actual and universal differences between the sexes, either quantative or qualitative."

Mead, Margaret (1937). "Letter". The American Anthropologist. 39: 558–561.

"All the claims so glibly made about societies ruled by women are nonsense. We have no reason to believe that they ever existed. ... men everywhere have been in charge of running the show. ... men have been the leaders in public affairs and the final authorities at home."

Mead, Margaret (1973). "Review of Sex and Temperament in Three Primative Societies". Redbook. October: 48.

Filipinos (and Filipinas, main entry Philippines)

"This combination of patterns has brought the Filipino woman to a point where, although denied some of the adventurous freedom of the male, she may be even better prepared for economic competition. The acceptance of the boredom of routine work may be seen as part of 'patient suffering' which is said to characterize the Filipino female to a greater extent than the male. Her responsibile role in the household means that the wife is charged with practical affairs while the husband is concerned to a greater extent with ritualistic activity which maintains prestige."

Hunt, CL (1965). "Female Occupational Roles and Urban Sex Ratios in the United States, Japan, and the Philippines". Social Forces. 43: 144.

Gahuku-Gama (main entry Fore people)

"At marriage a Fore woman ... is expected to be ... an obedient spouse, a prolific childbearer, and generous with gifts of food to her affines and her husband's friends."

Glasse (Lindenbaum), Shirley (1963). The Social Life of Women in the South Fore. Port Moresby: Department of Public Health, Territory of Papua and New Guinea. p. 1.

What is tastefully left out of this description is that food sometimes consisted of recently deceased members of the tribe. A disease called kuru, probably spread by this canibalism, affected more women, children and elderly than men. [Note again that anthropologists provide scientific observations not moral judgements.]

Hopi (main entry Hopi)

"It seems that brothers are assumed to be senior to sisters, and entitled to respect as such, in the absence of evidence to the contrary."

Freire-Marreco, Barbara (1914). "Tewa Kinship Terms from the Pueblo of Hano, Arizona". American Anthropologist new series. 16: 269–287.

"Within the family, the mother's brother, or, in his absence, any adult male of the household or clan, is responsible for the mainenance of order and the discipline of younger members."

Dozier, Edward P (1954). "The Hopi-Tewa of Arizona". American-Archaeology and Ethnology. 44: 339.

Iban (main entry Iban people)

"Typically, every bilek family has as its head a man who is responsible for the general management of the farm." (page 81)

The original ethnography is cited in Whyte, William King (1978). The Status of Women in Pre-Industrial Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

"The tuah rumah is the administrator and custodian of adat, Iban customary law, and the arbiter in community conflicts. He has no political, economic, or ritual power. Usually a man of great personal prestige, it is through his knowledge of custom and his powers of persuasion that others are induced to go along with his decisions. Influence and prestige are not inherited. The Iban emphasize achievement, not descent."

Quote from Martin J Malone's cultural summary drawn from sources including:

Gomes, Edwin H (1911). Seventeen years among the Sea Dyaks of Borneo: a record of intimate association with the natives of the Bornean jungles. London: Seeley.

The main Wikipedia entry above includes a short recent history of colonial politics and wars involving the Iban, up to the co-operation between Iban and Australians against Japanese in World War II.

The film, The Sleeping Dictionary, is set among the Iban.

Imazighen (also known as Berbers)

"Nuclear families are reported to be independent social groups only among the Mzab. Elsewhere they are aggregated into patrilocal extended families, each with a patriarchal head."

Murdock, George Peter (1959). Africa: Its people and Their Cultural History. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 117.

Iroquois (main entry Iroqois)

"The Indian regarded woman as the inferior, the dependent, and the servant of man, and from nurturance and habit, she actually considered herself to be so."

Morgan, Lewis Henry (1901). League of the Ho-Dêé-No-Sau-Nee or Iroquois. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company. p. 315.

"Ruling over the League was a council of 50 chiefs known as sachem[s] or lord[s]."

From Marlene M Martin's cultural summary, which draws upon the text quoted above.

Two interesting thing about this society are that the chiefs were elected, not hereditary, and that the voters were exclusively female.

See also:

Template:Harvard reference.

Randle, Martha C (undated). "Iroqois Women, Then and Now". Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin. 149. {{cite journal}}: Check date values in: |date= (help)

The main Wikipedia entry also provides enough circumstatial evidence to suggest what the anthropologists reported – the Iroqois were a matrilineal but patriarchal people.

Jivaro (see Jivaro)

"On relations between husband and wife it may be proper to say that it is regulated according to the principle 'the man governs, but the woman holds sway'."

Karstan, R (1935). The Headhunters of Western Amazonia:The Life and Culture of the Jibaro Indians of Eastern Ecuador and Peru. Helsingfors: Finska Vetenskaps-societeten Helsingfors. p. 254.

Kenuzi

"The subservient position of women was determined by the Islamic religion." (page 133)

"Women influence their husbands, but [their husband's] decisions are decisive." (page 89)

The original ethnographies are cited in: Whyte, William King (1978). The Status of Women in Pre-Industrial Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

It is also worth noting that in this society, girls are married before puberty (Godard, 1867), by adult men who inspect them manually for virginity (Kenedy, 1970). Female circumcision is later performed at puberty to ensure chastity (Barclay, 1964). [Once more we note that niether the anthropologists who report such practices, nor those who cite them, nor this article endorse these things in any way. These practices are mentioned only to explain why most scholars do not consider this society matriarchal.]

Kibbutzim (main entry Kibutz)

"Some women serve as secretaries of kibbutzim, very few as treasurers; women as economic directors are still a rarity. Experience in the internal positions of power is the stepping stone to external positions of power. There has been one woman national secretary of a kibbutz federation. The kibbutz federations usually send into national politics one token woman at a time."

Agassi, Judith Buber (1989). "Gender Equality: Theoretical Lessons from the Israeli Kibbutz". Gender and Society. 3: 160–186.

!Kung (main entry !Kung people)

"N≠issa's descriptions ... of her relationship with her husband, Tashay, suggest that relations between the sexes are not egalitarian, and that men, because of their greater strength, have power and can exercise their will in relation to women. This confirms Marshall's (1959) finding that men's status is higher than women's."

"The dominant impression one gets from accounts of patrilocal bands is one of semi-isolated, male-centered groups, encapsulated within territories."

"There are inherited positions, such as the 'headman'."

Marshall, Lorna (1976). The !Kung of Nyae Nyae. Cambridge, Massachusetts. p. 125. {{cite book}}: Unknown parameter |Publisher= ignored (|publisher= suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

"Raising 2 or 3 children to competent maturity—the life's work of a successful woman—has typically required hard decisions about priorities, attentive management of social relations, ingenuity, luck, and decades of hard labor."

Fielder, Christine (2004). Sexual Paradox Complementarity, Reproductive Conflict, and Human Emergence. New Zealand. ISBN 1-4116-5532-X. {{cite book}}: Unknown parameter |coauthors= ignored (|author= suggested) (help); line feed character in |title= at position 15 (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Maliku (also known as Minicoy Island)

"Maliku seamen then had small colonies in Burma, near Rangoon, and on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Nowadays, the men prefer to work on cargo ships owned by national and international shipping companies. Their 'Minicoy Seamen's Association' shifted from Calcutta to Bombay, where they teach the young men and supply employment."

"Until 1960, all the villages selected an additional authority, the rahubodukaka (lit. the country's big brother), who was in charge of the rahuge (lit. house of the country). He and the rahuweriñ (lit. ruler of the country), a boduñ selected by the boduñ and niamiñ [high status groups], were responsible for all the affairs concerning the whole island and the access to the southern part for collecting firewood and coconuts."

Kattner, Ellen (1996). "Union Territory of Lakshadweep: The Social Structure of Maliku". Institute for Asian Studies Newsletter. 10. {{cite journal}}: Text "pages19–20" ignored (help)

Minangkabau (main entry Minangkabau)

"In spite of the nominal 'matriarchate', Van Hasselt claims that the women are really the servants of the men. They not only prepare the meals of the men in their family, but they also serve them first, later eating with the children."

Paraphrase of:

"The women have not the legal right to make a contract, not even to dispose of themselves in marriage."

Both quotes from:

Loeb, EM (1934). "Patrilineal and Matrilineal Organization in Sumatra: The Minangkabau". The American Anthropologist. 36: 49.

More recently, Peggy Reeves Sanday observed the following:

"The Minangkabau are guided by a hegemonic idealogy called adat, which legitimizes and structures traditional political and ceremonial life." [Page 146]

"Thus, the Minangkabau make a distinction between female/weak and male/strong ..." [Page 149]

"In the specifics of male and female role definition, adat [sic] ideology is decidedly androcentric." [Page 150]

"First there are the ninik mamak, the men who have the authority to decide in accordance with adat law. The ninik mamak have authority over their nephews and nieces. [The ninik mamak] are the heads of the clan in the villages." [Page 151]

Mohammad Hatta, the first vice president of Indonesia, was a Minangkabau.

Mosuo (main entry Mosuo)

The Mosuo society is clearly both matrilineal and matrilocal, but not apparantly technically matriarchal. The Mosuo are a fascinating people, and the Wiki article is very informative. More information regarding the Mosuo as matriarchal, patriarchal or neither will be added here once it is located.

Nayar (main entry Nair)

"The Karanavan [mother's brother] was traditionally unequivocal head of the group... . He could command all other members, male and female, and children were trained to obey him with reverence." Gough, E Kathleen (1954). The Traditional Kinship System of the Nayars of Malabar (manuscript). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Social Science Research Council Summer Seminar on Kinship,Harvard University.

Quoted in:

Stephens, William N (1963). The Family in Cross-Cultural Perspective. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 317.

Tlingit (main entry Tlingit)

"The rank of chief ... passes from uncle to nephew."

Kraus, Aurel (1956). The Tlingit Indians. Seattle: Washington University Press. p. 77.

The excellent Wikipedia main entry provides a clear and detailed report of the matrilineality, matrilocality and patriarchy of this society.

Vanatinai (main entry Vanatinai)

"Almost all sorcerers on Vanatinai, who often exercise political and economic control over their neighbors, are male. ... No Vanatinai women have ever been elected as a Local Government Councillor."

Lepowsky, Maria (1981). Fruit of the Motherland: Gender and Exchange on Vanatina, Papua New Guinea. Berkley: Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of California. pp. 469–470.

Wemale

Traditional origin of headhunting:

"Then Latulisa [war chief and leader of the baileo] himself went to his sister who, at the time, was weaving a kanune [skirt], and he cut off her head. He hung up the head in the baileo [men's house] which now was nicely decorated. From that time on people practiced headhunting."

Traditional story of war starting as game of "tag", eventually the losers took revenge by killing:

"From that time on war was waged with weapons, and there was headhunting. It was agreed that women should never again fight."

Translated from German original:

Jensen, Adolf E (1939). Hainuwele: Volkserzählungen von der Molukken-Insel Ceram. Leipzig: Frobenius Institute.

Later commentary:

"[The Wemale men] filled-in their deficit as providers with ceremonial authority and with the terror of headhunting and cannibalism."

"Wemale men were obsolescent hunters who annually sacrificed a female Hainuwele [coconut girl] victim. Surely, they did not do so only because the mythical origin of tubers involved the death of a female dema deity, but also because the obsolescent hunters competed with their women for status."

Luckert, Karl W (1990). "Hainuwele and Headhunting Reconsidered". East and West: 261–279.

Woorani

"Kaempaede [a male] was, in short, the patriarch."

Man, John (1982). Jungle Nomads of Ecuador: The Woorani. Amsterdam: Time Life Books. p. 65.

"It is true that leadership does exist, but it is situational by nature. A man becomes a leader for a specific event, and when that event has passed, his cloak of leadership disappears."

Yost, James A (1981). "People of the Forest: The Woorani". Ecuador Ediciones. Libri Mundi: 109.

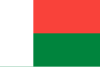

Yegali

This Madagascan tribe was mentioned in the textbook cited below. Hodges told Goldberg he'd heard about them from Donald Blender, but Goldberg and Hodges could find no evidence of them in any other academic literature.

Hodge, Harold (1971). Conflict and Consensus. New York: Harper and Row. p. 77.

See also

- Antifeminism

- Chinese patriarchy

- Gender role

- Homemaker

- Men's movement

- Pater familias

- Patriarch magazines

- Patriarchs (Bible)

References

- ^ Steven Goldberg, The Inevitability of Patriarchy, (William Morrow & Company, 1973).

- ^ Joan Bamberger,'The Myth of Matriarchy: Why Men Rule in Primitive Society', in M Rosaldo and L Lamphere, Women, Culture, and Society, (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1974), pp. 263-280.

- ^ Robert Brown, Human Universals, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), 1991.

- ^ Steven Goldberg, Why Men Rule, (Chicago, Illinois: Open Court Publishing Company, 1993).

- ^ Cynthia Eller, The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why an Invented Past Won't Give Women a Future, (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001).

- ^ Jonathan Marks, 'Essay 8: Primate Behavior', in The Un-Textbook of Biological Anthropology, (Unpublished, 2007), p. 11.

- ^ 'Matriarchy', Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007.

- ^ 'Matriarchy', Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007.

- ^ Margaret Mead,'Review of Sex and Temperament in Three Primative Societies'. Redbook (October 1973): 48.

- ^ William D Mounce, The Morphology of Biblical Greek, (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1994), p. 209.

- ^ Bauer, Danker, Arndt and Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon, 3rd ed., (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), pp. 137.

- ^ Alfred Rahlfs ed., Septuaginta, (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1979), p. 1.

- ^ Bauer, Danker, Arndt and Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon, 3rd ed., (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), pp. 138.

- ^ Genesis 25:12-18

- ^ Sura 37:99-109

- ^ John Stuart Mill, The Subjection of Women, (London: Longmans, 1868).

- ^ John Gerassi, 'Simone de Beauvoir: The Second Sex 25 Years Later', an interview with Simone de Beauvoir, Society 13 (January/February 1976), pp. 79-85.

- ^ Fredrika Scarth, The Other Within: Ethics, Politics and the Body in Simone de Beauvoir, (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), p. 100.

- ^ Mary Daly, Gyn/Ecology The Metaethics of Radical Feminism, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1978), p. 29.

- ^ Carole Pateman, The Sexual Contract, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988), p. 207.

- ^ Ronald Dworkin, Sovereign Virtue: The Theory and Practice of Equality, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), p. 2.

- ^ Judith Squires, Gender in Political Theory, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999), p. 97.

- ^ Steven Goldberg, Why Men Rule, (Chicago, Illinois: Open Court Publishing Company, 1993), p. 1.

- ^ Steven Goldberg, Why Men Rule, (Chicago, Illinois: Open Court Publishing Company, 1993), p. 11.

External links

- Jonathan Marks. 'Essay 8: Primate Behavior'. In The Un-Textbook of Biological Anthropology. Unpublished, 2007.

- 'Matriarchy'. Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2007.

- 'Cattle ownership makes it a man's world'. New Scientist (2003).

- Bible. Various translations.

- Qur'an. Translated by M.H. Shakir. New York: Tahrike Tarsile Qur'an Incorporated, 1983.

- Mary Wollstonecraft. A Vindication of the Rights of Women. Boston: Peter Edes for Thomas and Andrews, 1792.

- Simone de Beauvoir. The Second Sex. Translated by H M Parshley. London: Penguin, 1972.

- 'Equality'. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University, 2001.

- Times Literary Supplement review (by Mark Ridley) of The Inevitability of Patriarchy and reply by the author (Steven Goldberg).

- Same text as above, without formatting, at archive.org.

- Steven Webster. 'Was it Matriarchy?'. New York Review of Books (1972): 37-38.

- Phillip Longman. 'The Return of Patriarchy'. Foreign Policy (2006).

- The Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood website.

Literature

- Beauvoir, Simone de. Le Deuxième Sexe. Paris: Gallimard, 1949.

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. London: Jonathan Cape, 1953.

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1953.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Masculine Domination. Translated by Richard Nice. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001.

- Brown, Robert. Human Universals. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991.

- Eller, Cynthia. The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why an Invented Past Won't Give Women a Future. Boston: Beacon Press, 2001.

- Goldberg, Steven. The Inevitability of Patriarchy. New York: William Morrow & Company, 1973.

- Mead, Margaret. Male and Female. London: Penguin, 1950.

- Mead, Margaret. 'Do We Undervalue Full-Time Wives'. Redbook 122 (1963).

- Mies, Maria. Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour. Palgrave MacMillan, 1999.

- Ortner, Sherry Beth. 'Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture?'. In MZ Rosaldo and L Lamphere (eds). Woman, Culture and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1974, pp. 67-87.

- Pilcher, Jane and Imelda Wheelan. 50 Key Concepts in Gender Studies. London: Sage Publications, 2004.