94th Symphony (Haydn)

The . Symphony No. 94 in G major composed Joseph Haydn in 1791. The work was written as part of the first London trip, premiered on March 23, 1792, is titled with the drumbeat or Surprise (English: surprise ), and therefore also referred to as a bang symphony . The slow movement in particular is one of Haydn's best-known works.

General

For general information on the London symphonies, cf. Symphony No. 93 . The German title with the bang refers to an unexpected fortissimo blow in the second movement. It is "somewhat imprecise" in that, in addition to the timpani, all other instruments also participate in the corresponding beat. In England, the symphony was known as The Surprise , which is believed to have come from the flautist Andrew Ashe.

The two contemporary Haydn biographers, Georg August Griesinger and Albert Christoph Dies , report in different ways on the background of the Andante:

“I once asked him [Haydn] jokingly whether it was true that he had composed the Andante with the bang to wake the English who fell asleep in his concert? No, I got the answer, but it was my aim to surprise the audience with something new and to make a brilliant debut so as not to lose the rank of Pleyel , my student, who was at the same time was employed by an orchestra in London (in 1792) and its concerts opened eight days before mine. "

“With annoyance, Haydn remarked that even in the second act [of the concerts] the god of sleep kept his wings spread over the gathering. He saw this as an insult to his muse, vowed to avenge her, and for this end he composed a symphony in which, where it is least expected, he contrasted the andante, the softest piano, with the fortissimo. To make the effect as surprising as possible, he accompanied the fortissimo with timpani. (...) Haydn had asked the timpani to pick up thick sticks and hit them very ruthlessly. These also fully met his expectations. The sudden thunder of the whole orchestra startled the sleepers, everyone woke up and looked at each other with disturbed and puzzled expressions. (...) But since during the Andante a sensitive young lady was carried away by the surprising effect of the music, was unable to counteract it with sufficient nerve forces, and therefore fainted and had to be taken out into the fresh air, some used this incident as a material to criticize and said that Haydn had always surprised in a gallant way, but this time he was very rude. Haydn cared little about the criticism; its ultimate purpose, to be heard, was perfect and achieved even for the future. "

The symphony's great fame is based primarily on the second movement. This was also widely used in numerous instrumentations and arrangements, most of which were written in the first few years after the premiere. I.a. it concerns the texting of the main melody and z. Also some variations in different languages. One of the earliest arrangements for piano and voice is in English and Italian with the texts Hither com ye blooming fair and Per compenso offir non sò . The minuet was published in Bonn in 1811 as part of a quodlibet under the name Rochus Pumpernickl . Here the melody has been changed and put together with a strange trio. Haydn himself also edited the movement: In the aria of his oratorio Die Jahreszeiten , composed in 1801 , he lets the Ackermann flute the melody of this movement while working in the fields.

It is unclear whether Haydn composed the melody of the Andante entirely himself or whether it was entirely or partially taken from a folk song . On the one hand, the melody with its simple intervals and repeated tones is well suited to the performance of a text, on the other hand, the many textings speak against the existence of a well-known song.

In the first version of the second movement, the eponymous bang was not provided. However, since, according to contemporary newspaper reports, the bang in the first performance had a big impact, Haydn must have applied it beforehand and removed the second movement from the autograph . The relevant page has also been crossed out in the fragment contained, but the modified version in the composer's own handwriting has not yet been found.

Examples of statements on Symphony No. 94:

“The symphony […] has […] a simple and clear tonal structure. Of her four movements, three are in the main key, G major. The simplicity goes so far that even the introduction to the first movement and the trio of the minuet are written in G major. For the second [...] movement alone, Haydn chose a different key, namely the subdominant key of C major, and this movement is the only one in which a longer minor section occurs. Tonal tensions are virtually avoided throughout the work. "

“Overall, Symphony No. 94 is not overly complex, but it is also less easy to understand than the nickname suggests, which prompted not a few interpreters to focus solely on the surprise effect of the bang. The fact that No. 94 is more difficult to understand than the earlier cited "London Symphonies" may also be the reason why Haydn initially withheld the symphony composed in 1791 and only had it performed in 1792 as the fifth symphony in the series. "

“[The symphony] has in the course of the history of Haydn's reception achieved a popularity that is downright ruinous for a deeper understanding of this work: The 'Kettlebell' symphony occupies about the same place in the current Haydn repertoire as ' Eine kleine Nachtmusik ' in Mozart - or the 'Fate Symphony ' in Beethoven's repertoire. "

To the music

Instrumentation: two flutes , two oboes , two bassoons , two horns in D, two trumpets in D, timpani , violin I a. II, viola , violoncello , double bass . Numerous sources such as concert announcements, press reports and memoirs prove that Haydn conducted the symphonies of his first stay in London from the harpsichord (“ harpsichord ”) or the pianoforte or “presided”, as Burney put it (“ Haydn himself presided at the piano -forte ”). According to the performance practice at the time, this is an indication of the original use of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord or fortepiano) as a non-notated continuo instrument in the “London Symphonies”.

Performance time: approx. 25 minutes

When it comes to the sonata form used here, it should be noted that this model was only designed at the beginning of the 19th century (see there). - The description and structure and description of the sentences given here is to be understood as a suggestion. Depending on the point of view, other delimitations and interpretations are also possible.

First movement: Adagio cantabile - Vivace assai

Adagio cantabile: G major, 3/4 time, bars 1–17

The Adagio begins with a two-bar motif in G major in the winds, which is juxtaposed with another two-bar motif of the strings in the lower register. This leads to the dominant D major, so that both motifs act like question and answer. The motifs are repeated, the same with the wind player with the flute, while the string motif is now "closed" leading back to the G major tonic . The eighth- note movement of this motif is spun off and ends as a chromatically ascending tone repetition series with an accentuated bass movement in a dominant seventh chord, which represents the actual end of the introduction. The first violin leads with its falling eighth note figure to the following Vivace.

Vivace assai: G major, 6/8 time, measures 18–257

Overall, the movement has a dance-like character; It is characterized by the brevity of the main theme, the abrupt changes between forte and piano and the mostly continuous movement. The topics hardly contrast with each other.

The first theme is introduced at the beginning of the movement piano only by the two violins. The fourth up at the beginning of the topic reminds of the beginning of the introduction. The topic remains harmonious in the dominant area; only at the beginning of the fifth bar (bar 22) is the tonic reached with an abrupt “bubbling movement” in the forte tutti, which continues without a caesura. The keynote G is held for nine bars, while above it a change from tonic (G major) and dominant (D major) takes place at increasingly shorter intervals . Because of this and the shortening of the note values, the impression of acceleration (accelerando) is created. From bar 30 there is a turn to the dominant, which is played around for eight bars, with slowing down (ritardando) by lengthening or omitting (bass figure, omission of the wind instruments). In bar 38 only two melody tones of a dominant seventh chord are left, similar to the end of the introduction.

From bar 39, the first theme is repeated, now with another counterpart-like figure in the oboe. The following forte block of the entire orchestra (from bar 43) with tremolo and broken chords leads to the dominant. Another appearance of the first theme occurs in measure 54 in D minor with a subsequent Forte cadenza over A major to D major.

In measure 66, a new passage in D major begins, with an abrupt change from forte to piano, which can be viewed as a motif or an independent theme. It is a floating figure with virtuoso runs and a dance-like change between D major and A major. The figure is spun on with the addition of the wind instruments to the forte (bar 74).

Another theme (depending on your point of view, the second or third theme) follows in bar 80 piano in D major. It consists of a two-bar, repeated motif and a cadenza-like twist of three bars. The theme is repeated in various ways with wind participation and ends as a fallacy that leads to the final group (from bar 99) via a wind figure with trills in the 1st oboe. This is characterized by runs, unison movement and tone repetition. The exposition ends in bar 107 with the tone repetition on b in the 1st violin . It is repeated.

The implementation (clock 107-153) uses the first subject as a variant, the material is then continuously spun. From bar 123 , Haydn modulates with broken chords, which begin abruptly in the forte on A major and lead via D minor, B major and G minor to a passage with a chromatically descending movement (bars 134–140). This ends in F sharp major, which functions as a dominant to the following B minor. After a cadenza in B minor, tone repetitions on B, which (in contrast to the end of the exposition and development) sound together with G, announce the tonic and thus the recapitulation . The beginning of the reprise thus appears obscured. From bars 197-140 the timpani is retuned from D to A, ie the timpani changes in this section between the notes D and A (otherwise: G and D).

The recapitulation (from bar 154) initially begins according to the exposition, but the two repetitions of the first theme are missing. From bar 195, the second theme is followed by a passage-like passage in which the first theme appears three times: in the bass, in the upper parts and in unison. After the cadenza in bars 210 to 214, whose target note G is surprisingly played only by the horns in the piano, two more appearances of the theme follow in the 1st violin (from bar 219) and in the winds (from bar 222). The third theme follows immediately (bar 228), so that themes 1 and 3, which are far away in the exposition, are right next to each other and seem like two halves of a single theme. The final group known from the exposition (from bar 248) closes the movement.

Second movement: Andante

C major, 2/4 time, 156 bars, variation form. Possible structure:

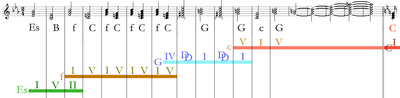

Presentation of the main theme bars 1–32 (see Fig. 2–3). The underlying, very simple and memorable melody is eight bars with four bars of the front and back notes. The basic component is a two-bar motif . The melody is initially accompanied by a single note at the beginning of the bar in the bass. After its first run (bars 1–8) the theme is repeated, now in pizzicato- pianissimo. In bar 16, a fortissimo beat of the whole orchestra in G major (the “bang”) starts suddenly after the melody has already ended at the beginning of bar 16. As if nothing had happened, there are now four bars of another motif (B part of the theme), which with its sixteenths is somewhat more flexible than the preceding, rather rigid A part. Then (bars 21-24) the A part is repeated as a variant, so that a basic structure of ABA or the three-part song form results. Bb and A are now repeated again with wind participation before the actual variations begin.

In detail, the following structure results for the topic (see Figure 2):

These motifs can be assigned to melodically and harmoniously contrasting areas (Fig. 3):

- Three- or four-tone (a, b, c, a ', c') - scale (d, d ')

- ascending (a, a ') - descending (b, c, d, d', c ')

- Tonic of C major (a, a ', c' 2nd bar ) - Dominant of C major (b, d, d ', c' 1st bar )

Contrasting areas can also be identified rhythmically:

- The motifs a, b and a 'consist of a chain of six eighths and one quarter that mark the end of the motif.

- The motifs d and d 'are enriched by a dotted rhythm / sixteenth notes. Therefore, the beginning of the second part seems livelier than the first. These sixteenths are just "filler notes" or decorations.

The first variation (bars 33–48, C major, figs. 4–5) begins with another Fortetutti strike (no longer fortissimo). 2nd violin and viola play the theme, while 1st violin and z. T. Insert the flute (for motif c) with a voice against. This opposing voice (Fig. 5) essentially runs in thirds and sixths parallels to the theme, but condenses the uniform rhythm of the eighth notes of the theme into a chain of sixteenth notes through leading and passage notes. The first bar of motif d 'is an exception, here the sixteenth notes of the theme are set against eighth notes in the accompaniment. In the last two bars (motif c ') the accompanying voice and theme run parallel.

The second variation (bars 49–74, C minor, figs. 6–8) shortens the four opening bars of the first half (fortissimo, unison of the whole orchestra) with the four closing bars of the second half (strings, piano) linked. Instead of the expected second half, there is then a free spinning in forte with dialogue between 1st and 2nd violin on E flat major, F minor and dotted rhythms in unison. The transition to the 3rd variation takes place via a falling figure on the 1st violin.

The third variation (bars 75-106, C major) plays around the basic notes of the theme with broken thirds in a sixteenth-note movement. The repetitions of the front and back sentences are composed because they differ from one another in terms of minor deviations. First, the 1st oboe, accompanied by the strings, performs the motifs a and b, rhythmicized by sixteenth-note repetitions. The rest of the variation is performed by a trio: the theme, both violins played in unison , takes over the bass function as the lowest voice, flute and 1st oboe add an opposing voice. When repeating the B part, the horns join in to support the harmony. In the motif d 'the flute temporarily takes over the main notes of the theme, the final notes (motif c') are changed to f'-g'-c 'to emphasize the cadence subdominant - dominant - tonic. Haydn later used the material of this trio part in aria No. 4 "Already eilet glad der Ackersmann" of his oratorio "The Seasons".

The fourth variation (bars 107-138, C major, fig. 9) is march-like and pompous. The A section is initially fortissimo and uses the full orchestra with syncopated accompaniment. Before the B part follows in the forte, another complete cycle with a completely different character for strings and bassoon in the piano is switched on, with the A part taking over the dotted rhythm from the B part (bars 115-130, possibly as variation no . 5 interpretable). In the repetition of the antecedent, motif a in violins I and II shows a further rhythmic and melodic variation, motif b is moved to the lower parts and accompanied by the two violins with the upper part already known from variation 1, which is, however, accompaniment in the subsequent movement .

A coda (from bar 139) with fanfare and subsequent reverberation of the theme over sustained seventh and seventh chords of the strings and an organ point on C ends the movement.

Michael Walter interprets the sentence to mean that Haydn wanted to deceive the audience's expectations with the intentionally banal and simple theme and the “artistic artlessness” of the variations. B. also the fortissimo beat from the beginning for the further course of the sentence without consequences. Donald Francis Tovey associates the theme of waddling across a poultry farm in different variations with goose-like solemnity. In the third variation, the oboe seems to have laid an egg.

Third movement: Menuetto. Allegro molto

G major, 3/4 time, with trio 89 bars

The minuet is composed of several phrases that are combined and varied in new ways. Also noteworthy is the tempo designation, which is clearly detached from the dance menu, is identical to that of the fourth movement and points in the direction of the Scherzo , which later established itself as the third movement in symphonies. The movement begins forte as a rural melody (bars 1–8), with the flute, bassoon and 1st violin leading the voice. The melody consists of progressive quarters with jumps and detached movement, except for the eighth bar. From bar 9, a new part in the piano follows in contrast with a pendulum figure in the dialogue between upper voice and bass. The first half of the minuet ends with a cadence figure with eighth barrel.

The second half begins imitatively with the eighth figure, which ended the first half. The final part of this figure is then spun on (from bar 25) and supported with distinctive chord strikes (from bar 28, a sequence of subdominant seventh chord and associated tonic). After four bars of lingering on the dominant, the prelude in the upper parts sounds like an echo, which is unexpectedly answered by its reversal in the bass before the main melody starts again from the beginning of the sentence. The theme is not brought to an end, but remains on the dominant for five bars, including the fermata and drum roll. The final section of the minuet follows with repeated upbeat turns in the tonic in G major: the pendulum figure from bar 9 sounds over an organ point on G.

The trio is also in G major and is designed for strings and bassoon in the piano. The cadence figure from the end of the first part of the minuet appears again as an inversion (downwards instead of upwards) in combination with interval leaps in quarters. The first half of the trio is symmetrical in 4 + 4 bars. In the second half, the interval figure is sequenced from quarters. The return to the main melody of the trio is delayed by continuous repetitions of the opening figure, so that a new metric focus is temporarily created.

Fourth movement: Finale. Allegro (di) molto

G major, 2/4 time, 268 bars

The first theme with a dance-like character is built up periodically and is first presented by the strings piano. After the repetition of the theme with flute, a new part for strings follows (B part of the theme, bars 17–30), which is followed by the repetition of the opening melody (A part) (bars 31–37, now next to the strings also with flute and bassoon). For the further structure of the sentence, on the one hand, the opening phrase of the topic (motif 1), a sixteenth phrase from the B part (motif 2) and the final turn of the first topic in measure 37 (motif 3) are important. Without a break, a transition section follows in the forte-tutti. While the violins play continuous runs, motif 3 and motif 1 appear in the bass. From bar 59 the 2nd violin and the viola play the head of the first theme. After a chromatically descending chord progression, the passage ends as a cadence on the dominant, the target chord of which, however, is replaced by a general pause (bar 74). This draws attention to the second topic that is now beginning.

Like the first theme, this is in the piano, is presented by the strings and consists of two four-bar units, of which the first is repeated. With the exception of the final cadence, the theme represents a swing between tonic and dominant, with the bass constantly repeating the note D. Haydn uses motif 1 as accompaniment in the 2nd violin. In the final group (from bar 87), sixteenth-note runs of the violins and chord melodies dominate. The exposition ends in bar 99 with three forte beats on D and continues without repetition (alternatively, the end of the exposition could also be seen in bar 103).

The development begins with a double repetition of the quarter beats on C, which work harmoniously as a dominant seventh chord for the following appearance of the first theme in G major. This gives the listener the impression that the exposition is being repeated (here, however, with the bassoon, but without at the beginning of the sentence). Deviating from this, however, from bar 112 there is a passage with motif 3 in the bass and strong harmonic changes, especially from bar 121 (C major - A major - D major - B major - E minor to bar 124). By repeating motif 1, on the one hand, the action calms down, on the other hand, another run through of the first theme is announced from bar 146. The surprising appearance in forte with the theme in G minor marks the beginning of the following modulation section over the B keys (E flat, F and B flat major), with motif 2 in the violins also appearing in fortissimo (from bar 160). After modulating back to the dominant D major, there is a stop in sixteenths in the 1st violin.

The recapitulation (from bar 182) is designed as a shortened sequence of the exposition: The repetitions of the first theme are omitted, it appears immediately with the B part; in addition, the section between the two main topics has been shortened. Immediately after the second theme there is a coda (from bar 222) with motif 1 in the piano and a surprising turn to E flat major with the first theme in the forte, announced by a drum roll. The movement ends with chord melodies in fortissimo, with motif 3 in between (measure 255).

Ludwig Finscher (2000) thinks of this sentence that "the thematic thoughts only serve to trigger a dizzying, kaleidoscopic abundance of thematic transformations (...)." The structure of the sentence can - as with some other final movements of the London symphonies - as a mixture can be interpreted between sonata form and rondo ("sonata rondo").

Individual references, comments

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Stähr: Symphony in G major. Hob. I: 94 ("With the bang"). In: Renate Ulm (Ed.): Haydn's London Symphonies. Origin - interpretation - effect. On behalf of the Bavarian Broadcasting Corporation. Joint edition Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag Munich and Bärenreiter-Verlag Kassel, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7618-1823-7 , pp. 101-106

- ^ Robert von Zahn: London Symphony, 2nd episode. In: Joseph Haydn Institute Cologne (ed.): Joseph Haydn works. Series I, Volume 16. G. Henle-Verlag, Munich 1997, page VIII.

- ^ Albert Christoph Dies: Biographical news from Joseph Haydn. Based on oral accounts of the same, designed and edited by Albert Christoph Dies, landscape painter. Camesinaische Buchhandlung, Vienna 1810. Re-edited by Horst Seeger with a foreword and notes. Reprinted by Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kassel, without a year (approx. 1960), pp. 94 to 95.

- ↑ a b c d e f Marie Louise Martinez-Göllner : Joseph Haydn - Symphony No. 94 (bang). Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-7705-1609-5 .

- ↑ Michael Walter (2007), page 111: The theme consists, "apart from the repetitions, from two eight-bars (...) and is of such an uncharacteristic simplicity that one has tried to legitimize it as a folk song quote - either “Go up and down in the Gässle” or “ Ah, vous dirai-je, Maman ”, which was also varied by Mozart - but apart from melodic differences to the folk songs, the theme lacks any quotation character. "

- ↑ a b Michael Walter: Haydn's symphonies. A musical factory guide. CH Beck-Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-44813-3 .

- ↑ Information text on the performance of Symphony No. 94 on October 2, 2010 at the Haydn Festival Eisenstadt, http://www.haydn107.com/index.php?id=32 , as of August 2010.

- ^ In German translation by HC Robbins Landon: Joseph Haydn - his life in pictures and documents . Verlag Fritz Molden, Vienna et al., 1981, p. 124: "Haydn himself presided over the piano-forte."

- ↑ HC Robbins Landon, David Wyn Jones: Haydn: his life and music , Thames and Hudson, London 1988m pp. 232-234.

- ↑ Not noted, d. H. Unnumbered continuo was relatively common; even for some of JS Bach's cantatas , unnumbered continuo basses have been preserved - despite the high harmonic complexity of Bach's music.

- ↑ On the use of the harpsichord as an orchestral and continuo instrument around 1802, Koch writes in his Musikalischen Lexicon , Frankfurt 1802 , under the heading “wing, clavicimbel” (pp. 586–588; wing = harpsichord): “ […] The other genres of these Clavierart, namely the spinet and the clavicytherium, have fallen completely out of use; The grand piano is still used in most of the large orchestras, partly to support the singer with the recitative, partly and mainly to fill in the harmony by means of the figured bass ... Its strong, penetrating tone, however, makes it the fulfillment of the full-voiced music All very clever; therefore he will probably compete in major opera houses and bey numerous occupation of votes the rank of very useful orchestral instrument until another instrument of equal strength, but more mildness or flexibility of the sound is invented which to lecture the basso well is sent. […] In clay pieces according to the taste of the time, especially with a weak cast of the voices, […] one has begun for some time now to swap the grand piano with the weaker, but softer fortepiano . "

- ↑ James Webster takes the London symphonies from his idea that Haydn did not use a harpsichord (or other keyboard instrument, especially fortepiano) for continuo playing (“ And, of course, the argument refers exclusively to pre-London symphonies and performances outside England "; In: James Webster: On the Absence of Keyboard Continuo in Haydn's Symphonies. In: Early Music Volume 18 No. 4, 1990, pp. 599-608, here: p. 600).

- ^ Howard Chandler Robbins-Landon (ed.): Joseph Haydn: Sinfonia No. 94 G major "Paukenschlag / Surprise" Hob. I / 94. Series: Critical edition of all symphonies. Philharmonia No. 794, Universal Edition, Vienna without year, 67 p. With appendix. Pocket score with a proposal for a sentence structure

- ↑ a b Ludwig Finscher: Joseph Haydn and his time . Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2000, ISBN 3-921518-94-6

- ^ GA Marco: A Musical Task in the "Surprise" Symphony. In: JAMS. Vol. 11, 1958, p. 41 ff. Quoted in: Marie Louise Martinez-Göllner (1979)

- ^ Donald Francis Tovey: Essays in Musical Analysis. Symphonies and other Orchestral Works. - Haydn the Inaccessible. - Symphony in G major: The surprise (Salomon, No. 5; chronological List, No. 94). London, 1935–1939: “The theme of the slow movement, when taken as an andante according to Haydn's present instruction, has an anserine solemnity which undoubtedly enhances the indecorum of the famous Paukenschlag. (...) in this symphony it waddles through the poultry-yard in several variations, the first being in the minor and inclined to episodic developments. At the return to the major mode the oboe seems to have laid an egg. "

- ↑ In the Philharmonia pocket score, the beginning of the reprise in measure 145.

- ↑ The drum roll changes one measure before the other instruments from piano to forte and is reminiscent of the corresponding passage in the Andante as a “bang”.

Web links, notes

- Audio samples of Haydn's 94th Symphony from the project "Haydn 100 & 7" of the Haydn Festival Eisenstadt

- Thread on Symphony No. 94 by Joseph Haydn with a discussion of various recordings

- 94th Symphony (Haydn) : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Symphony no. 94 is available as a PDF on MuseData.org available

- Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 94 G major (bang - surprise). Ernst Eulenburg Ltd No. 435, London / Zurich without year (pocket score)

- Joseph Haydn: Sinfonia No. 94 G major “Paukenschlag / Surprise” Hob. I / 94. Philharmonia No. 794, Universal Edition, Vienna without year, 67 p. With appendix. Series: Howard Chandler Robbins Landon (ed.): Critical edition of all symphonies. (Pocket score).

- Robert von Zahn: London symphonies 2nd episode. In: Joseph Haydn Institute Cologne (ed.): Joseph Haydn works. Series I, Volume 16. G. Henle-Verlag, Munich 1997, 209 pages.