100th Symphony (Haydn)

The Symphony in G major Hoboken directory I: 100 wrote Joseph Haydn in 1794. The work belongs to the famous "London Symphonies", was premiered in London on March 31, 1794, entitled "Military Symphony" .

General

For general information on the London symphonies, cf. Symphony No. 93 . Haydn composed Symphony No. 100 in 1794 as part of his second trip to London. The corner movements were probably written shortly after arriving in London, while the middle movements were written in Vienna. For the Allegretto, Haydn resorted to the variation movement from one of the Concerti for two organ eggs (Hob.VIIh: 3 *), which he had written for King Ferdinand IV of Naples in 1786/87 (Haydn also performed other works in the London concerts which he originally composed for King Ferdinand, with the organ eggs replaced by flute and oboe).

The title “Military Symphony ” is not entered on the autograph , but Haydn used it at the concert on May 4, 1795, at which Symphony No. 104 was also premiered. The title refers to the second and fourth movements, in which the association of a military band arises through the use of kettledrum, triangle, cymbal and bass drum (the second movement also contains a trumpet signal). This type of music emerged after 1720 as a result of several Turkish wars in Venice and Austria, was influenced by the military bands of the Janissaries (Turkish foot troops) and especially popular in Vienna as "Turkish music" (see also Janissary music ). (At the premiere, the audience was probably closer to the association with the armed conflicts in France than the historical retrospect on the Turks.) There were numerous French refugees in London at the time.

The symphony was premiered on March 31, 1794 at the “Salomon's Concerts” in London's Hanover Square Rooms . The Morning Chronicle reports of the repeat performance on April 9, 1794: “[...] and the middle movement was again greeted with unqualified applause. Encore! Encore! Encore! It resounded from every seat: Even the ladies were getting impatient. It's the approach to battle, the march of the men, the sound of the store, the thunder of the beginning, the clank of weapons, the groaning of the wounded and what has been called the infernal roar of war - increased to a climax of hideous Urgency !, which, if others can imagine it, can only be carried out by Haydn alone; because he alone has so far achieved this miracle. ” After another performance on May 2nd, however, the newspaper also mixed in critical undertones against the use of Turkish music in the final movement (see there).

The Allgemeine Musikische Zeitung wrote in April 1799 about the symphony: “It is a little less learned and easier to grasp than some of the other of its most recent works, but as rich in new ideas as it is. Perhaps the surprise cannot be carried further in the music than it is here, through the sudden incursion of the full Janissary music in the minor of the second movement - since up to then one has no suspicion that these Turkish instruments are appropriate for the symphony. But here too, not only the inventive, but also the level-headed artist shows himself. The andante is, of course, a whole: for with everything that is pleasant and easy that the composer, in order to derive deceptively from the idea of his coup, brought into the first part of the same, it is laid out and worked on like a march. "

Symphony No. 100, along with No. 94, was Haydn's most popular symphony in England, especially the Allegretto. Haydn reworked this movement for a wind orchestra, and many other arrangements were made for domestic use (piano trio, string quartet, etc.). For various interpretations of the work in literature, see the second sentence.

To the music

Instrumentation: two flutes , two oboes , two clarinets in C (these only in the Allegretto), two bassoons , two horns in G, two trumpets in C, timpani in G and D, two violins , viola , cello , double bass . The following are special features: triangle , Turkish cymbal pair, bass drum . Numerous sources show that Haydn conducted his symphonies at the London concerts from the harpsichord and from 1792 from the “ Piano Forte ”, as was the performance practice at the time. This indicates the use of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord or fortepiano) as a continuo in the "London Symphonies".

Performance time: approx. 25-30 minutes.

With the terms of the sonata form used here, it should be noted that this scheme was designed in the first half of the 19th century (see there) and can therefore only be transferred to Haydn's Symphony No. 100 with restrictions. The description and structure of the sentences given here is to be understood as a suggestion. Depending on the point of view, other delimitations and interpretations are also possible.

First movement: Adagio - Allegro

Adagio : G major, 2/2 time (alla breve), measures 1 to 23

The strings begin with the participation of the solo bassoon piano with a two-bar motif, which is noticeable with its “questioning” fourth at the beginning and the dotted rhythm. It is carried on by a similar motif. The starting motif is then repeated, but with a different continuation towards the dominant D major (bar 8). In the further course a clouding takes place through the use of chromatics up to the fortissimo outbreak with drum roll in minor (bar 14f.) And the following general pause. If the upbeat rhythm of the opening motif (starting with the whole bar) has already been emphasized, it is emphasized even more strongly with the slow new approach in the piano. The introduction ends as a throbbing, broken D major - triad in unison. With the fourth up and down at the beginning of the movement, there is a thematic reference to the following Allegro (similar to the beginning of Presto).

Allegro : G major, 2/2 time (alla breve), measures 24 to 289

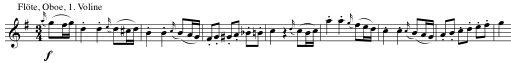

The first theme (bars 24 to 38) with its periodic structure stands out due to its contrasting instrumentation: the first movement is performed by the high woodwinds (flute and oboes), the subsequent movement by the strings. It is possible that this instrumentation ( “marching band” ) is to be understood as the first reference to the military echoes, especially in the Allegretto. In bar 39 the transition begins as a tutti block in the forte (the first theme was entirely piano). It first emphasizes the tonic in G major, but then establishes the dominant D major with a series of chromatically descending quarters and A major scale runs, in which the beginning of the first theme now sounds again. The head of the theme in the dramatic D minor forte leads over to the second theme.

The upbeat second theme begins over a carpet of strings (from measure 93) with the first violin leading the voice, in measure 98/99 the solo flute and bassoon join. The instrumentation is thus the opposite of that for the first topic. Both topics have the character of a "speed march" . That the second issue at the beginning of a resemblance to 1848 by Johann Strauss (father) composed Radetzkymarsch having, belongs to the realm of legends: the march theme of the Radetzky March is almost note for note for its "Cheers Quadrille" (part: "Finale" op. 130, 1841) and influenced at most precursors (opp. 12 and 18 by Johann Strauss (father) from 1828, ie at the beginning of his compositional career). To today's listener, this alleged association may sound even more marching with the second subject than the first. The theme leads into the final group (bar 108 ff.), In which the first motif of the theme is taken up in the bass. After eighth-notes and chord melodies, the exposition ends in bar 124 in D major and is repeated.

The implementation begins unexpectedly with two clocks general pause (as if the sentence already over) to which the second theme begins - but not as usual in D major, but in harmony distant B major. The further course is characterized by changes from forte / fortissimo and piano, accents (bars 158 ff.) And key changes, with Haydn particularly emphasizing the rhythm of the second theme in unison. In measure 169, when B minor is reached, there is a brief caesura, on which the head starts from the first theme as a dialogue between woodwinds and strings (starting in E minor). As a result, the marching rhythm of the second theme dominates again, partly in unison and reinforced with syncopation . In the return to the recapitulation (bars 195 f.) The action ebbs, in which only the strings and finally the flute and oboes play.

The recapitulation (from bar 203) is different from the exposition: The ending of the first theme is played as tutti and forte, and the transition to the second theme is almost completely omitted. Instead of the final group after the second theme, Haydn uses a fortissimo outbreak in the surprising E flat major (bar 239), which in turn draws on the marching rhythm of the second theme. Then the material of the transition that has just been omitted is made up for (eighth runs, sequence of chromatically descending quarters) until the extended final group (from bar 273) ends the movement like a code .

Second movement: Allegretto

C major, 2/2 time (alla breve), 186 measures

The sentence can be broken down into the following sections:

- First section: Presentation of the graceful main theme in the piano, characteristic rhythm with two quarters and four eighths. Voice guidance initially in solo flute and 1st violin, then alternating between woodwinds (including clarinet) and strings with solo flute. A part in C major (bars 1–16), middle part B in the dominant G major (bars 17–28), repetition of A part (bars 29–36), B part, bars 37–48) and again A section (bars 49–56).

- Second section: Variation of the main theme in C minor with changed instrumentation (tutti), with cymbals, bass drum, triangle, chromatics, the sharp alternation of forte and piano and the accents causing the exotic “Turkish” timbre.

- Third part: Changed repetition of the first part: Part A and B in tutti (bars 92–111), Part A in tutti with cymbals, bass drum and triangle (bars 112–119), B part in woodwinds (bars 120– 133), decorated A section in the tutti including the striking mechanism. The music then comes to rest pianissimo in C major (bar 151).

- Fourth part (coda): Beginning with a low-lying trumpet signal in the 2nd trumpet, which may represent an Austrian military signal. Beginning pianissimo, a drum roll swells to an A flat major breakout in fortissimo, again with the percussion instruments. As if nothing had happened, a contrasting piano passage follows (bar 167) with the main motif in the woodwind line-up. The end in C major with continuous pounding of the percussion is determined by the change forte-piano, the end of the movement by emphasizing the signal-like fourth GC in unison.

In particular, the Allegretto is discussed and interpreted in literature:

"Of course, the movement is not program music [...] with the deployment of armies and the tumult of battle, but it does open up the association background of the war in a very emphatic way, without any stylization, rather with all the terrible features in the aforementioned association. Major "catastrophe" and the C minor variation, in which Turkish music begins for the first time. "

“In the aforementioned theatrical moments, especially because of the armed conflicts between England and France at the time, there is a risk of hearing a kind of“ program music ”in the 100 Symphony. But this would be an overinterpretation of the European "alla-turca" taste of the times, which Haydn used suggestively. "

“Rather, Haydn uses the discordant and the ugly here [...] in order to clarify the sublimity of the beautiful, which only becomes clear before this ugly. At least that's the case in the second sentence. The contrast between "ugly" Turkish music and the artistic march is most evident in its variant, orchestrated with woodwinds and horns, in measure 92 ff. "

“[...] a pianissimo drum roll ends after two bars in a fortissimo outcry from the entire orchestra, which suddenly breaks down the three central parameters of western music. There is neither a recognizable harmony nor a perceptible rhythm, let alone a melody - for six bars the music roars out its horror. "

Third movement: Menuet. Moderato

G major, 3/4 time, with trio 80 bars

The main theme of the minuet has a distinctive rhythm with an upbeat sixteenth note suggestion and two knocking quarters. The first part is not repeated true to note, but as a piano variant with a different instrumentation. At the beginning of the middle section, Haydn worked very closely with his head from the main theme in terms of motifs, so that it takes on the character of a development (e.g. the eighth run up from the first part now also like opposing voices). After an echo, the prelude appears in bar 31 on every beat of the bar, so that the listener's metric orientation is briefly confused. The “recapitulation” begins after a passage falling freely in triplets in bar 43 with a coda-like ending, in which the knocking motif in fortissimo is briefly extended to three quarters.

The trio is also in G major and its timbre is determined by the parallel flute, oboes and violins. The “gracefully elegant” main theme, which “looks like a quote from the world of gallant style” , consists of a dominant seventh chord falling in dotted rhythm , followed by two ascending triad breaks. The middle section contains a four-bar, strongly contrasting minor insertion, which hammers a threatening line with chromaticism above the organ point on D, and with its dotted rhythm is reminiscent of the military character of the previous movements.

Fourth movement: Finale. Presto

G major, 6/8 time, 334 bars

The first theme (or: rondo theme, since the movement is in the form between rondo and sonata form: "sonata rondo") is made up of three parts: First (bars 1–8) the theme is introduced in the piano of the strings and repeated (A- Part). It is structured periodically and has a characteristic four-fold tone repetition in the first phrase of the antecedent (motif A, bars 1–2), in the second phrase a figure that loosens briefly (motif B, bars 3–4). Both motifs are upbeat and characterized by the continuous eighth-note impulse, which gives the subject (and the whole movement) its propulsive, hastily scurrying character. This leads the listener to expect a typical sweeping conclusion. The middle section (B) begins with a strong contrast to motif A in the forte tutti on E minor, only to switch pianissimo to B major shortly afterwards. The dominant D major is in measure 17 with motif B and in measure 26f. with staggered use of motif A, briefly striped. The energetic, hammering eighth note movement is then lost with the "questioning" motif A (as dominant seventh chord) in solo flute and oboe, and after a general pause the main theme (A part) is picked up again pianissimo. With this one can see a three-part structure ABA in the topic. The section from bar 9 is also repeated. The eight-bar main melody was in the 19th century as a popular dance tune titled Lord Cathcart or Lord Cathcart known so that Haydn probably can be considered as an author of a popular melody here while otherwise mostly drew on existing folk songs.

The following transition (bar 50 ff.) Represents a forte block with modulations of motif A and triad breaks in rapid eighth notes. Quarter beats in forte and piano separated by general pauses announce the second theme, which begins after a short dialogue between bass and solo flute (bars 86 ff.). It is in the dominant D major and is played piano by the strings. The bass and 1st violin lead in a dialogue of separate staccato quarters with suggestions, while the other strings create an accompanying "carpet" in the eighth tremolo. The 1st violin then continues the suggested quarters. These are also taken up in the forte tutti at the beginning of the final group (bars 94 ff.), But then again merge into the rapid eighth note chains of the strings. The final group ends with the quarter beats already known from bars 75 ff., Separated by general pauses, but then unexpectedly a forte drum roll hits the third general pause (possibly interpreted as a cannon thunder / gun salvo) and closes the exposition with two quarter beats in the forte. Karl Geiringer compares the effect with the "bang" from Symphony No. 94 :

“A similar effect, but used even more effectively, is found in the finale of No. 100. Here two chords are played first piano, then, after another general pause, pianissimo by the strings. Before the listener has fully savored the irritating effect, the kettledrum breaks in with fortissimo beats. By skipping the expected third general pause, the composer completely takes his audience by surprise. "

The development (from bar 123) begins piano with motif A in D minor of the strings. The further course contains numerous modulations and alternates between hesitant piano passages, which are interrupted by general pauses, and energetic forte sections. Already in bar 132 there is a motif made up of four quarters (motif C), initially ascending, later mostly ascending. It is somewhat reminiscent of the motif with the four chromatically descending quarters of the Allegro (there e.g. bars 58 f.). In measure 146, the second theme in A flat major is achieved that changes via motif C to D flat major. The mysterious and eerie passage from measure 166 with motif C in the pianissimo of the strings contrasts strongly with the forte block from measure 182, which begins with motif A in E major. The dialogue between bass and solo flute (bars 202 ff.) Is reminiscent of the transition to the second theme from the exposition. Instead of the second theme, however - similar to bar 38 - motif A appears as a “questioning” dominant seventh chord, which serves as an announcement for the recapitulation.

The recapitulation begins after two bars of a general pause (bar 218) and is shortened compared to the exposition: the first theme is repeated once forte in the tutti, and then, starting from E flat major, moves on to a development-like section with motif A staggered (similar to measure 26 ff). The rapid eighth-note chains lead directly to the second topic, now already like a group of groups in the forte and with the use of the striking mechanism. Further eighth note chains lead into the coda, which takes up the first theme again and ends the sentence “noisy” with the participation of all instruments.

The second use of the “Turkish” instruments in the Presto was and is sometimes rated negatively in terms of showmanship.

See also

Web links, notes

- Audio samples and score of Haydn's 100th Symphony from the project “Haydn 100 & 7” at the Haydn Festival in Eisenstadt

- 100th Symphony (Haydn) : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Symphony no. 100 is available as a PDF on MuseData.org available

- Thread on Symphony No. 100 by Joseph Haydn with a discussion of various recordings

- Wolfgang Marggraf : The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn. - Symphony 100, G major ("Military Symphony"), accessed May 26, 2011 (text as of 2009)

- Joseph Haydn: Sinfonia No. 100 G major. Philharmonia No. 800, Universal Edition, Vienna 1967. Series: Howard Chandler Robbins Landon (Ed.): Critical edition of all symphonies (pocket score).

- Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 100 G major (Military). Edition Eulenburg No. 434. Ernst Eulenburg Ltd., London / Zurich without indication of the year (pocket score)

- Horst Walter: London symphonies 3rd episode. In: Joseph Haydn Institute Cologne (ed.): Joseph Haydn works. Series I, Volume 17. G. Henle-Verlag, Munich 1966, 233 pages

Individual references, comments

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Rüdiger Heinze: Symphony in G major, Hob. I: 100 (“military”). In: Renate Ulm (Ed.): Haydn's London Symphonies. Origin - interpretation - effect. On behalf of the Bavarian Broadcasting Corporation. Joint edition Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag Munich and Bärenreiter-Verlag Kassel, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7618-1823-7 , pp. 159–166.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Ludwig Finscher: Joseph Haydn and his time . Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2000, ISBN 3-921518-94-6 , p. 376 ff.

- ^ Declaration of war by France on Austria in 1792, intervention of England in the conflict after the execution of King Louis XVI. January 21, 1793 execution of Marie Antoinette on 16 October 1,793th

- ^ Anthony van Hoboken: Joseph Haydn. Thematic-bibliographical catalog raisonné, volume I. Schott-Verlag, Mainz 1957, 848 pp.

- ↑ a b Anonymous: Joseph Haydn. Symphony No. 100 in G major, Hob.I: 100, "Military". Text accompanying the concert on March 31, 2009 at the Haydn Festival in Eisenstadt, as of July 2010.

- ↑ HC Robbins Landon: Joseph Haydn - his life in pictures and documents , Fritz Molden Verlag, Vienna et al., 1981, pp. 123-124

- ↑ Koch writes about the use of the harpsichord as an orchestral and continuo instrument around 1802 (!) In his Musikalischen Lexicon , Frankfurt 1802 , under the heading “wing, clavicimbel” (pp. 586–588; please consider that at this time wing = harpsichord !): “ ... The other genres of this type of keyboard (ie keel instruments , author's note), namely the spinet and the clavicytherium , have completely fallen out of use; the grand piano (ie the harpsichord , author's note) is still used in most of the major orchestras, partly to support the singer with the recitative , partly and mainly to fill in the harmony by means of the figured bass ... being strong penetrating sound makes it (ie the grand piano = harpsichord, author's note) very adept at filling the whole thing with full-voiced music; therefore he will probably compete in major opera houses and bey numerous occupation of votes the rank of very useful orchestral instrument until another instrument of equal strength, but more mildness or flexibility of the sound is invented which to lecture the basso well is sent. ... in clay pieces according to the taste of the time, especially with a weak cast of the voices, ... for some time now the grand piano has been swapped for the weaker, but softer, fortepiano . "

- ↑ Even James Webster, one of the main proponents of the anti-harpsichord continuo thesis, takes the London symphonies from his idea that Haydn did not use a harpsichord (or other keyboard instrument, especially fortepiano) for continuo playing (“ And, of course "The argument refers exclusively to pre-London symphonies and performances outside England "; in: James Webster: On the Absence of Keyboard Continuo in Haydn's Symphonies. In: Early Music Band 18 No. 4, 1990, pp. 599-608, here : P. 600). This is because the well-documented fact that Haydn conducted the symphonies from the harpsichord (or pianoforte) usually also meant continuo playing at this time (see quotation from Koch's Musicalisches Lexikon , 1802 in the previous footnote).

- ↑ Jürgen Mainka: Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 100 in G major Hob. I: 100 (1794). In: Malte Korff (ed.): Concert book orchestral music 1650-1800. Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden / Leipzig 1991, ISBN 3-7651-0281-4 , pp. 385-387.

- ↑ a b Michael Walter: Haydn's symphonies. A musical factory guide. CH Beck-Verlag, Munich 2007, 128 pp.

- ↑ Kurt Pahlen ( Symphony of the World. Schweizer Verlagshaus AG, Zurich 1978, pp. 164–165): "It is therefore possible that both themes - that of Haydn and that of Strauss - go back to an old Austrian source."

- ↑ Finscher (2000): "[...] the subordinate sentence (from which Johann Strauss' father was inspired in 1848 when composing the Radetzky March) [...] "

- ↑ Information text on Symphony No. 100 in the project “100 & 7” of the Haydn Festival in Eisenstadt: “The secondary theme of the first movement has often been said to anticipate the ' Radetzky March ' ."

- ↑ Jubel-Quadrille, Op. 130 on YouTube with the march theme of the Radetzky March anticipated as early as 1841 starting at 3:26 minutes

- ↑ Mainka (1991), on the other hand, describes the theme as a "swaying, serenade-like melody."

- ↑ In part (e.g. Heinrich Eduard Jacob ( Joseph Haydn. His art, his time, his fame. Christian Wegner Verlag, Hamburg 1952) refers to the similarity or equality of the theme with that of the second movement of the symphony no Van Hoboken (1957) rejects this, however: “With the romance from“ La Reine ”, this melody […] only has the eighth figure in common in the second half of the first measure, which in both works has a different melodic context stands."

- ↑ Depending on your point of view, the woodwind section can be understood as idyllic serenades or - as in the first theme of the Allegro - as an allusion to a military band.

- ^ Introductory text and overview of forms in: Joseph Haydn: Symphony 100 (XI) G major. Wiener Philharmonischer Verlag AG, No. 35, Vienna without a year (approx. 1950). Pocket score

- ↑ Heinze (2007): "It is said to have been known as the" parade mail "of the Austrian cavalry until the outbreak of World War II (Schering 1940)." [Arnold Schering: Comments on Joseph Haydn's program symphonies . In: Yearbook of the Peters Music Library. Volume 46, 1940 edition]

- ^ Karl Geiringer: Joseph Haydn. The creative career of a master of the classics. B. Schott's Sons, Mainz 1959, p. 237

- ↑ Morning Chronicle for performance on May 2, 1795: “We cannot help remarking, that the cymbals introduced in the military movement, though they there produce a fine effect, are in themselves discordant, grating, and offensive, and ought not to have been introduced, either in the last movement of that Overture, or in the Finale at the close of the Concert. " (quoted in Finscher 2000)