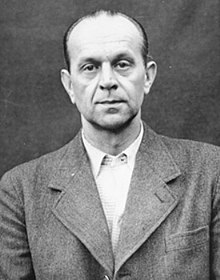

Adolf Pokorny

Adolf Pokorny (born July 26, 1895 in Vienna ; † unknown) was a dermatologist born in Austria and a defendant in the Nuremberg medical trial . He was accused of instigating and participating in sterilization experiments in the Nazi prison camps, but was acquitted in 1947.

Life

Origin and training as a soldier in the First World War

Adolf Pokorny was the son of an Austrian military officer. Due to the frequent transfers of his father within Austria-Hungary , the family lived in Bohemia, Galicia and Bosnia, among others. Before his hometown was occupied by the German army in 1938 as a result of the Munich Agreement , he had Czechoslovak citizenship.

Pokorny took part in the First World War as a soldier from March 1915 to September 1918 . As a lieutenant he was dismissed with numerous awards and shortly afterwards began studying medicine at the University of Prague . In 1922 he completed this with a doctorate and received his medical license on March 22, 1922 . After two years in a clinic, he worked as a resident dermatologist in Komotau from 1924 and specialized in skin and venereal diseases.

family

In 1923, Adolf Pokorny married Lilly Weil, a colleague of Jewish origin. The two had two children together who brought them to safety in England before the Second World War . Due to this marriage, which was divorced in April 1935, Pokorny's application for membership in the NSDAP failed in 1939 . He was charged with the divorce at the Nuremberg doctors' trial as evidence of his hostility towards "racially inferior" people. In contrast, his defense lawyers claimed that the separation occurred by mutual consent and as a result of personal differences.

The time of National Socialism and the letter to Himmler

Pokorny belonged early to the German-Völkisch Irredenta in Bohemia , which sought to join the German Empire .

During the Second World War, he was last employed as a Wehrmacht medical officer in a military hospital in Hohenstein-Ernstthal .

In October 1941 Pokorny wrote a letter to Himmler in his function as Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Ethnicity . In his own words, "Carried by the thought that the enemy must not only be defeated but destroyed" , he submitted the proposal to attempt sterilization on people with the South American silent pipe plant ( Caladium seguinum ). Pokorny referred Himmler to a publication by Madaus AG on this plant. In it, Gerhard Madaus had discovered that the juice of the silent pipe caused permanent sterility, especially in animals. With reference to “three million Bolsheviks currently in German captivity”, he advocated immediate human attempts to “exclude them from procreation ”. In order not to endanger the experiment, he advised Himmler to start growing plants immediately and, furthermore, not to allow Madaus any further publications in order to avoid the "enemy" becoming aware of these plans. Himmler instructed Oswald Pohl and Ernst-Robert Grawitz to follow up Pokorny's information and to contact Madaus so that he could “ sound out the possibility of experiments on criminal persons who would have to be sterilized in and of themselves” . However, it soon turned out that the plant, which is native to South America, could have been produced too slowly and in insufficient quantities due to the climatic conditions. Although it therefore seemed to Himmler and his experts unsuitable for the planned mass sterilization, Himmler urged that experiments be carried out in the concentration camps at least with the existing substances in the plant. By the end of the war there were no usable results from experiments with the silent pipe plant.

Pokorny as a defendant in the Nuremberg medical trial

Pokorny worked in the health department in Munich in 1945 , most recently as a senior physician. In 1946 he was indicted in the Nuremberg doctors trial. As a resident dermatologist, Pokorny had a special position in the group of defendants. He was the only one among them who had not been a member of the NSDAP and had never held a position of responsibility in the hierarchy. In the course of the process, Pokorny defended himself to the effect that he was aware of the ineffectiveness of the silent pipe and that he wanted to dissuade Himmler from using tried and tested methods of sterilization with his suggestion. He pretended to have heard of the planned sterilization programs for Jews and residents of the Eastern Territories. He wanted to prevent these plans by pointing out the silent pipe plant as a diversionary maneuver.

The court did not follow Pokorny's account, but acquitted him anyway:

“We are not impressed by the defense the defendant has put forward, and it is difficult to believe that he was guided by the noble motives he claims when he wrote the letter. Rather, we tend to think that Pokorny wrote the letter for very different and more personal reasons. […] In the Pokorny case, the prosecution has failed to produce evidence of his guilt. Outrageous and low as the proposals in this letter are, there is not the slightest evidence that any steps have ever been taken to try to apply them to humans. We therefore declare that the accused must be acquitted, not because of but in spite of the defense he has put forward. "

literature

- George J. Annas, Michael A. Grodin (Eds.): The Nazi Doctors and the Nuremberg Code. Human Rights in Human Experimentation . Oxford University Press, New York 1992, ISBN 0-19-507042-9 .

- Angelika Ebbinghaus , Klaus Dörner (ed.): Destroying and healing . The Nuremberg medical trial and its consequences . 1st edition. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-351-02514-9 .

- Ernst Klee: Auschwitz, Nazi medicine and its victims . Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-596-14906-1 .

- Alexander Mitscherlich, Fred Mielke: Medicine without humanity. Documents of the Nuremberg Doctors' Trial . Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-596-22003-3 .

Web links

- Documents on Pokorny from the Nuremberg Doctors Trial at the Nuremberg Trials Project

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Klaus Dörner , Karsten Linne (ed.): The Nürnberger Ärzteprocess 1946/47. Verbal transcripts, prosecution and defense material, sources on the environment. Saur, Munich, 1999 (microfiche edition)

- ↑ Biographical information in: Klaus Dörner (Ed.): The Nürnberger Ärzteprocess 1946/47. Verbal transcripts, prosecution and defense material, sources on the environment. Access tape. Saur, Munich, 1999, ISBN 3-598-32020-5 , p. 132. Ernst Klee : Das Personenlexikon zum Third Reich - Who was what before and after 1945. Fischer paperback, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-596 -16048-8 , p. 468.

- ↑ Angelika Ebbinghaus , Klaus Dörner (Ed.): Destroying and healing. The Nuremberg medical trial and its consequences . Berlin 2001, p. 637.

- ↑ quoted in Alexander Mitscherlich , Fred Mielke: Medicine without humanity. Documents of the Nuremberg Doctors' Trial. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-596-22003-3 , pp. 307f. The letter in the facsimile ( memento of July 13, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (Nuremberg document NO-035) at the Nuremberg Trials Project.

- ^ Ernst Klee : Auschwitz, Nazi medicine and its victims. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-596-14906-1 , p. 437.

- ↑ Complete quote from Ernst Klee : Das Personenlexikon zum Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945 . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, second updated edition, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 978-3-596-16048-8 , p. 468.

- ↑ Ernst Klee : Auschwitz, Nazi medicine and its victims. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-596-14906-1 , p. 438.

- ↑ Mitscherlich: Medicine , p. 310 f.

- ↑ Udo Benzenhöfer : Nürnberger Ärzteprozess: The selection of the accused. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 1996; 93: A-2929-2931 (issue 45) (PDF, 258KB).

- ↑ Alexander Mitscherlich, Fred Mielke: Medicine without humanity. Documents of the Nuremberg Doctors' Trial. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-596-22003-3 , p. 238

- ↑ Justification of the judgment p. 240 f, quoted in Mielke: Medicine , p. 308 f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pokorny, Adolf |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German dermatologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 26, 1895 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | 20th century |