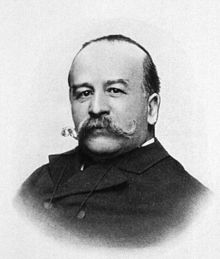

Alexandre Lacassagne

Alexandre Lacassagne (born August 17, 1843 in Cahors , southwestern France, † September 24, 1924 in Lyon ) was a French doctor and criminologist . He was the founder of the Lacassagne Criminology School in Lyon, which was very influential from 1885 to 1914 and the main rival of Lombroso's Italian School .

Life

He studied at the Strasbourg Military School and for a short time worked at the Val-de-Grâce Military Hospital in Paris . Later he became a seat of the Médecine Légale de la Faculté de Lyon ( forensic medicine at the Faculty of Lyon ) and was also the founder of the journal Archives de l'Anthropologie Criminelle . Among his assistants was the famous forensic scientist Edmond Locard (1877–1966).

Lacassagne was a major pioneer of the fields of medical jurisprudence and criminological anthropology . He was a specialist in toxicology and pioneered blood stain pattern analysis and research into bullet markings and their relationship to specific weapons.

He was very interested in sociology and psychology and the correlation between these two disciplines and criminal and "deviant" behavior. He considered the biological predisposition of the individual, as well as his social environment, to be an important factor in criminal behavior.

Lacassagne became famous for his expertise in various criminal cases , including the " malle à gouffé " in 1889, the assassination of President Sadi Carnot , who was stabbed to death by the Italian anarchist Caserio in 1894 , and Joseph Vacher (1869–1888), one of the earliest serial killers on record Of France.

In politics, Lacassagne supported the initiative of his friend Léon Gambetta , an opportunist republican , who favored the "May 27, 1885 Act", also known as the "Law to Banish Repeat Offenders " (the bill was laid down by René Waldeck-Rousseau and Martin Feuillée ), which enabled the establishment of penal colonies . He also opposed the abolition of the death penalty , proposed in 1906 by an alliance of radicals and socialists , but rejected in 1908 because he believed some criminals were incorrigible.

Lacassagne school

Lacassagne's school had great influence in France from 1885 to 1914 and was the main antagonist of Lombroso's Italian school, although its importance was overshadowed and only recently rediscovered by the influence of recent work by historians. Summing up his main subjects in 1913, Lacassagne noted:

- "The social environment is the breeding ground for crime; the germ is the criminal, an element that has no meaning until the day it finds the food that makes it ferment."

- " We oppose the fatalism, which inevitably follows from anthropological theory , with social initiative."

- "Justice withers, prison corrupts, and society has the criminals it deserves."

Lacassagne was originally influenced by Lombroso, but began to contradict himself about his later theory of the "born criminal", the "criminal type" and his insistence on heredity . Through the influence of sociologist Gabriel Tarde , Lacassagne put emphasis on environmental influences, although in his view environmental determinism did not rule out hereditary issues or physical anomalies.

Lacassagne shared a common admiration for Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828), the founder of phrenology , with Paul Dubuisson , the co-founder of the Archives d'anthropologie criminelle , and Joseph Gouzer . He was also influenced by Auguste Comte's positivism ; he started one of his articles with a quote from Michelet who claimed that "the science of justice and natural science are one." Indeed, Lyon was an important center of phrenology, with the presence of Fleury Imbert (1796-1851), a disciple of Fourier who married Gall's widow, and Émile Gromier (1811-78), Lacassagne's predecessor in the Lyon faculty. A third important influence of Lacassagne was hygienism . From these influences he preserved two main principles: organism and cerebral localization .

The Lyon school defined crime as "an anti-physiological movement that occurs in the intimacy of the social organism". They assumed that the social environment had a physiological influence on the brain, thus opposing Lombroso's theory, which claimed that criminal factors are not only biological, but exclusively individual. From then on, according to Lacassagne, the two most important factors for criminological studies were "biological" and "social"; the social itself was viewed as a biological organism. According to Gall's theory of cerebral localization, he divided the brain into three zones, the occipital zone, the seat of animal instinct, the parietal zone, which is used for social activities, and the frontal zone, the seat of superior ability. He further subdivided society itself on the basis of these zones, which according to him produced three "types" of criminals, "thought criminals", "acting criminals" and "sensitive or instinctive criminals", or corresponding to the frontal, parietal zone and occipital social zone .

Lacassagnes was possibly overshadowed by the Lombroso School because of his adherence to the values of phrenology, which at the time was denied credibility by most scientific circles. Criminology at that time was split into two main tendencies, one more related to "bio-psychological" theories, claiming the importance of individual factors and aiming at establishing an essential distinction between respectable citizens and criminals, and the other related to medical determinism social opposed, mainly influenced by Durkheim . Lacassagne's approach, which combined biological and social factors, was too ambiguous to exist.

Fonts

- De la Putridité morbide et de la septicémie, histoire des théories anciennes et modern (1872)

- Précis d'hygiène privée et sociale (1876) On-line

- Précis de médecine judiciaire (1878) On-line

- Les Tatouages, étude anthropologique et médico-légale (1881)

- Les Actes de l'état civil: étude médico-légale de la naissance, du mariage, de la mort (1887)

- Les Habitués des prisons de Paris: étude d'anthropologie et de psychologie criminelles (1891) On-line

- Les Établissements insalubres de l'arrondissement de Lyon. Comptes rendus des travaux du Conseil d'hygiène publique et de salubrité du département du Rhône (1891)

- Le Vade-mecum du médecin-expert: guide médical ou aide-mémoire de l'expert, du juge d'instruction, des officiers de police judiciaire, de l'avocat (1892) On-line

- L'Assassinat du président Carnot (1894) On-line

- De la Responsabilité médicale (1898) On-line

- Vacher l'éventreur et les crimes sadiques (1899) On-line

- Précis de médecine légale (1906)

- Peine de mort et criminalité, l'accroissement de la criminalité et l'application de la peine capitale (1908)

- La Mort de Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1913)

- La Verte Vieillesse (1920)

See also

- History of psychology

- Alphonse Bertillon

- Marc-André Raffalovich (1864–1934), employee of the Archives d'anthropology criminelle , wrote about homosexuality.

Web links

Individual evidence

- This article is based on a translation from the English Wikipedia.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Marc Renneville, La criminologie perdue d'Alexandre Lacassagne (1843-1924) , Criminocorpus , Center Alexandre Koyré -CRHST, UMR n ° 8560 of the CNRS , 2005

- ↑ Malle à gouffé Affair ( Memento of the original dated February 28, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ French: «le milieu social est le bouillon de culture de la criminalité; le microbe, c'est le criminel, un élément qui n'a d'importance que le jour où il trouve le bouillon qui le fait fermenter »

- ↑ French: 'au fatalisme qui découle inévitablement de la théorie anthropologique, nous l'opposons initiative sociale "

- ^ French: "la justice flétrit, la prison corrompt et la société a les criminels qu'elle mérite"

- ↑ Alexandre Lacassagne (quoted by Marc Renneville), "Les transformations du droit pénal et les progresses de la médecine légale, de 1810 à 1912" ( Memento of the original from June 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Archives d'anthropologie criminelle , 1913, p. 364.

- ↑ A. Lacassagne et Étienne Martin, "Etat actuel de nos connaissances en anthropologie criminelle pour servir de préambule à l'étude analytique des travaux nouveaux sur l'anatomie, la physiologie, la psychologie et la sociologie des criminels" ( Memento of the original from June 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Archives d'anthropologie criminelle , 1906, pp. 104-114. (quoted by Renneville)

- ↑ French: "mouvement antiphysiologique qui se passe dans l'intimité de l'organisme social" , Joseph Gouzer , "Théorie du crime" ( Memento of the original from June 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and still Not checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Archives d'anthropologie criminelle , 1894, p. 271 (quoted by Renneville)

- ↑ Today the brain is divided into several regions, including the occipital, parietal, and frontal lobes.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lacassagne, Alexandre |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French doctor and criminologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 17th August 1843 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cahors , South West France |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 24, 1924 |

| Place of death | Lyon |