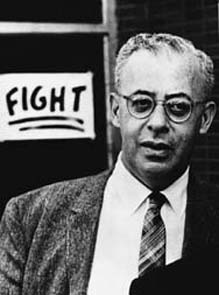

Saul Alinsky

Saul David Alinsky (born January 30, 1909 in Chicago , Illinois , USA ; † June 12, 1972 in Carmel , California , USA) was an American civil rights activist , pioneer of community organizing and founder of the Industrial Areas Foundation .

Life

Saul D. Alinsky grew up in the Jewish quarter of Chicago, an area that Alinsky later called "the slum district of the slum" ( English for: the slum within the slum ). Alinsky was brought up and trained in a strictly Jewish Orthodox manner, but, contrary to the hopes of his parents, was aloof from her faith. After completing his school career, he enrolled in 1926 at the University of Chicago , where he first made a bachelor's degree in archeology . During his archeology studies, he took part in events organized by the sociologist Ernest Burgess . His increased social commitment as well as the dwindling professional opportunities for archaeologists due to the global economic crisis led to Alinsky's archaeological career being broken off.

As part of a graduate scholarship , Alinsky began to study criminology and sociology in 1930 . He had an ambivalent relationship to sociology, because on the one hand he was fascinated by the research fields, but he had a deep distrust of academics and especially of sociologists, who in his perception were unrealistic. In particular, Alinsky criticized the detachment from the research object as insufficiently dealing with the individual suffering and misery of the people in the slums . As a result, he broke off his studies in 1938. Still, many methods of empirical social research, as well as the theories and models developed at the Chicago School of Sociology , formed the basis for Alinsky's later approach. In particular, the method of nosing around ( participatory observation ), which he had learned while working in various university research projects , became part of his methodology. Furthermore, William I. Thomas' approach of the Four Wishes as a motive structure for all actions formed the basis for Alinsky's own personality theory. Specifically, the essay by Ernest Burgess Can Neighborhood Work have a Scientific Base? was the impetus for Alinsky's interest in neighborhood work.

In 1935 Alinsky worked on the Chicago Area Project , a research project by Ernest Burgess and Clifford Shaw , which was to develop concepts for expanded options for action in the prevention of juvenile delinquency. Alinsky's role was to identify key people in the Back of the Yards (meat packing district) on Chicago's west side. At the same time, unionist John L. Lewis founded the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in response to the policies of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), the largest US skilled workers' union at the time. As the umbrella organization of industrial workers, the CIO made it possible for the first time to bring together all of the previously independent individual unions in industrial production. Lewis thus created an "organization of organizations". Lewis' organizing campaign in the meat packaging industry coincided with Alinsky's work on the Chicago Area Project . This is how they got to know each other and Alinsky began to take part in the CIO's organizational campaign. Lewis became one of Alinsky's most important teachers. However, it was clear to Alinsky that he could not be a trade unionist. Against the background of the increased emergence of fascist movements trying to take advantage of the hopelessness of the slum dwellers, Alinsky developed the idea of founding a civic umbrella organization based on the Lewis model to unite the local institutions, clubs and organizations in the neighborhood. In this way the position of the district could be strengthened in negotiations for better living conditions.

Community organizing according to Saul Alinsky

On July 14, 1939, the founding convention of the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (BYNC) took place. Almost all important local organizations, trade unions (AFL and CIO), business people, representatives of sports and social clubs, teachers and priests were represented in the Council (the Catholic priests occupied 1/3 of the committee seats). As one of the first acts, the BYNC declared its solidarity with the local trade union group PWOC, which had been initiated by the CIO. This alliance was a novelty, because previously there had been no alliance between the Catholic Church and a left-wing trade union organization. Alinsky had managed to unite both parties in the struggle for better living conditions in the district. Thanks to this alliance, medical care was improved, rubbish collection reorganized, recreational facilities created, a lunch table for children with 1,200 hot meals a day, a summer camp program for the children and a community fund, which also made improvements.

Alinsky clearly differentiated his work at BYNC from social work , which he accused of pursuing welfare colonialism and being paternalistic. Alinsky understood his own role in BYNC from the beginning as that of a "technician". He saw himself as an external teacher and supporter, not a leader of the movement. The community organizing should focus on local democracy based not on an external authority. His approach was based on the subsidiarity principle of the Catholic social doctrine , according to which small social units had to be put in a position to solve their problems themselves. Intervention by larger social units (usually the state) would therefore only be permitted and required if this principle failed. Another approach adopted by Alinsky comes from the sociologist William I. Thomas , according to which the self-controlled organizations of immigrants were of central importance for integration into American society. In his books he gave short, precise, rule-like and sometimes controversial references to the political struggle, as he saw social sympathy, especially for the have-nots.

In response to the success of the BYNC, Alinsky co-founded the Bishop of Chicago's Catholic Archdiocese , Bernhard J. Sheil , and Marshall Field III, millionaire and owner of a successful department store chain, Kathryn Lewis, daughter of union leader John L. Lewis, and Joseph Meegan, who had previously been involved in setting up the BYNC, founded the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) in 1939 . The IAF was supposed to serve as an advisory and coordination point for citizens' organizations that were active in neighborhoods that had problems comparable to those of the back-of-the-yards neighborhood. In addition, the IAF served as financial security for Alinsky, who from then on worked as a professional organizer .

Some of Alinsky's greatest civil society successes have been organizing campaigns to improve living conditions in ghettos for Afro-Americans in Chicago (Woodlawn, 1958), and to promote equality for black workers at Eastman Kodak in Rochester (1964).

Saul D. Alinsky died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1972. His student and long-time colleague Edward T. Chambers took over the management of the Industrial Areas Foundation, which he held until his death in 2015. The Industrial Areas Foundation is now the largest network for community organizing in the USA with 56 associated local organizations in 21 states of the USA, Canada, Great Britain and Germany.

reception

Former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton wrote her graduate thesis at Wellesley College on Saul Alinsky in 1969 . The work received a lot of attention in 2008 during the Democratic Party's primary election for the US presidential election, because in connection with the frequent abuse of Alinsky as a communist due to his proximity to the unions , Clinton was to be portrayed as a left-wing radical. It is no longer publicly available. Alinsky’s influence on Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama appears nonetheless to have been substantial.

Fonts (selection)

- Rules for Radicals. A practical primer for realistic radicals. Reprint. Vintage Books, New York NY 1989, ISBN 0-679-72113-4 (first edition 1971).

- Reveille for Radicals. Reprint of 2nd updated edition. Vintage Books, New York NY 1991, ISBN 0-679-72112-6 (first edition 1946).

- Instructions for being powerful. Selected Writings. (German translation by Reveille for Radicals). 2nd Edition. Lamuv Verlag, Göttingen 1999, ISBN 3-88977-559-4 ( Lamuv-Taschenbuch 268).

- Call Me a Radical: Organizing and Enpowerment - Political Writings. Karl-Klaus Rabe (editor, translator), Regina Görner (editor), Eric Leiderer (editor), Saul D. Alinsky (author). Lamuv Verlag, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-88977-692-1 , (reprint of the translation by Karl-Klaus Rabe from instructions on how to be powerful in cooperation with IG Metall Jugend).

- John L. Lewis. An Unauthorized Biography. Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish MT 2007, ISBN 978-1-4325-9217-2 .

- A Sociological Technique in Clinical Criminology. In: American Prison Association: Proceedings of the Sixty-fourth Annual Congress of the American Prison Association . WB Burford, Indianapolis IN 1932, ISSN 0065-7948 , pp. 167-178.

- Community Organization and Analysis. In: American Journal of Sociology , May 1941, ISSN 0002-9602 , pp. 797-808.

literature

- Lukas Foljanty: Broad-based Community Organizing in the USA. In: Heike Hoffmann, Barbara Schönig, Uwe Altrock (eds.): Civil society as a bearer of hope? Governance, nonprofits and urban development in the metropolitan areas of the USA . Uwe Altrock Publishing House, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-937735-06-1 ( Planungsrundschau 15 series ).

- Leo Penta (Ed.): Community Organizing. People change their city. Edition Körber Foundation, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-89684-066-0 ( American ideas in Germany 8).

- Peter Szynka: Theoretical and empirical basis of community organizing with Saul D. Alinsky. (1909-1972). A reconstruction. Academy for Work and Politics of the University of Bremen, Bremen 2005 (published 2006), ISBN 3-88722-656-9 ( Bremen contributions to political education 3; also: Bremen, Univ., Diss., 2005).

- Jim Rooney: Organizing the South Bronx. State University of New York Press, Albany NY 1995, ISBN 0-7914-2210-0 ( Suny series, the new inequalities ).

- Sanford D. Horwitt: Let Them Call Me Rebel - Saul Alinsky. His Life and Legacy. Vintage Books, New York NY 1989, ISBN 0-679-73418-X .

- Robert Slayton: Back of the Yards. The Making of a Local Democracy. Paperback edition. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL 1988, ISBN 0-226-76199-1 .

- Marianne Freyth: Saul David Alinsky. An American theory of practice. Conflict strategies in the fight against poverty. LIT-Verlag, Münster 1985, ISBN 3-88660-201-X ( Studies on Political Science 4; also: Münster (Westphalia), Univ., Diss.).

- Manuel Castells : The City and the Grassroots. A Cross-cultural Theory of Urban Social Movements. University of California Press, Berkeley CA 1983, ISBN 0-520-05617-5 ( California series in urban development ).

- Jane Jacobs [1961]: The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Modern Library Edition. Modern Library, New York NY 1993, ISBN 0-679-60047-7 (first edition 1961).

Web links

- Industrial Areas Foundation

- Forum Community Organizing e. V.

- German Institute for Community Organizing

- Article on Saul D. Alinsky TIME Magazine

- The Democratic Promise; TV documentary about Alinsky and the Industrial Areas Foundation

Individual evidence

- ↑ progress.org ( Memento from September 12, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Robert E. Park, Ernest W. Burgess, Roderick D. McKenzie: The City. Suggestions for Investigation of Human Behavior in the Urban Environment. [1925] The University of Chicago Press, London 1987, ISBN 978-0-226-64611-4 , p. 142 ff.

- ^ Rules for Radicals. A practical primer for realistic radicals. Reprint. Vintage Books, New York NY 1989, ISBN 0-679-72113-4 (first edition 1971), translated in Berliner Hühnerhochhaus : Excursion to Chicago: Saul Alinsky's rules for radicals , accessed March 23, 2016

- ↑ industrialareasfoundation.org ( Memento from February 25, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ “There Is Only The Fight…”: An Analysis of the Alinsky Model in the English language Wikipedia

- ↑ msnbc.msn.com

- ↑ See for example http://www.hillaryproject.com/index.php?/en/story-details/hillary_obama_and_the_cult_of_alinsky/ ( Memento from October 20, 2007 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ npr.org

- ↑ Peter Slevin For Clinton and Obama, a Common Ideological Touchstone , Washington Post, March 25, 2007, accessed April 1, 2018

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Alinsky, Saul |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Alinsky, Saul David (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American civil rights activist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 30, 1909 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Chicago , Illinois |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 12, 1972 |

| Place of death | Carmel , California |