Old Serbian rulers' biographies

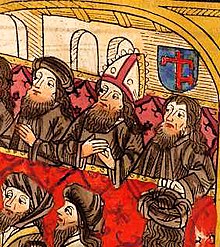

The biographies of the old Serbian rulers originated between the 13th and 15th centuries. They have a special position in the Byzantine culture (the so-called "Byzantine Commonwealth") shaped Slavic countries of Southeast and Eastern Europe and differ as a special literary form from Byzantine models. The old Serbian rulers' biographies describe the life of Serbian rulers and church princes. In them, the history of ideas and the historical reality of the Serbian Middle Ages meet. This makes them the most important source for medieval Serbian rulership and a place for contemporaries to contemplate the reality that surrounds them. From the origin of the genre in the short vita of his father Stefan Nemanja written by Sava of Serbia , written by Stefan Nemanjić , Dometijan , Teodosije Hilandarac , Danilo II. , Danilo III. , Konstantin von Kostenec and Grigorij Camblak the corpus of the biographies.

origin

The old Serbian rulers' biographies go back to small forms of Byzantine historiography and the popular form of Greek hagiography . The starting point of the genre are the two texts describing Stefan Nemanja's biography by his two sons Sava and Stefan. Sava's short description of Stefan Nemanja's monk life was followed by Nemanja's biography of King Stefan Nemanjić (also Stefan the First Crowned), which was about twice as large. Both texts date from the beginning of the 13th century. Like all later biographies, they were written in Orthodox monasteries. As a sociological place of the old Serbian biography, these were centers of the house tradition of the Serbian nobility, who organized the monasteries in a more manorial and aristocratic manner. In the biographies, members of the ruling house or the monasteries have their say as members of the leading political classes. The life descriptions are therefore not only a form of description of history, in them history should also be made.

function

The Vites were intended to be read aloud in the monastic community, for the table reading at the ruler's court or as a teaching aid for the noble youth in the monastery and cathedral schools. The ecclesiastical and religious moments of the Viten are a determining element. They determined the world of thoughts and ideas of the Middle Ages in which, according to Stanislaus Hafner, the "metaphysical was considered a reality".

Emergence

Savas Vita Stefan Nemanja from 1208 was created as part of the Typikon of the Studenica Monastery in the burial place of Stefan Nemanjas, who was canonized at the beginning of the 13th century, determined by Sava. It was therefore necessary to confirm the cult around Nemanja through the Vita and to influence the environment in this sense. Sava's concern in the Vita was already presented in the Proömien in Hilandar's deed of foundation on Holy Mount Athos , which was based on the deeds of the Byzantine emperors. Following this guiding principle, it became the model for all other ruler biographies of the Serbian Middle Ages. With this, the Serbian biography was placed in the service of the ruling house from the beginning. The second Vita of Stafan Nemanjas by Stefan Nemanjić, following the Vita Savas, is considered a prime example of medieval dynastic historiography. In it the justification of one's own threatened succession to the throne and the will to influence the events of the time become clear.

With the two following vites of Savas by the Hilandarm monks Dometijan and Teodosije, the state ideological form of the Serbian ruler's biographies, elaborated further in the vita, experiences its two essential forms: the learned-rhetorical and the popular-edifying. Dometijan and Teodosije lay the foundation for the "ideal" solution of the relationship between state and church in the Nemanjid Empire . This idea arose in Serbian monasticism. Nemanja as the founder of the state and his son Sava as the first head of an autocephalous Serbian state church withdrew all power rivalries between church order and secular rule. According to Hafner, the common relationship between the founder of the state and the dynastic ancestor and the metaphysical teacher of ideas was "anchored in the metaphysical and dynastic realm for all times". From then on, monasticism served as the guardian of this connection.

content

The Viten are the most important sources of the Serbian rulers history of the Middle Ages and provide essential details on the historical events. Stefan Nemanja's first vita included the last years of Stefan Nemanja's life as a monk Simeon, in which his abdication and entry into the Studenica monastery are told. It is written as an eyewitness account from Sava of Serbia. Stefan joined his son in the Vatopedi monastery as an Athos monk . Sava describes the arrival of his father until his death. At that time, the Hilandar Monastery was built by Simeon and Sava from Emperor Alexius III. left personally as a foundation. In terms of content and structure, Savas Vita differs considerably from the formal structure of medieval Greek vitae; it only partially follows rhetorical customs and the conventions of contemporary Byzantine hagiographies. In a simple style, as well as through the humble and reserved formulations in which the author speaks about himself, it has retained a quality to this day that also touches today's readers. After Stefan was canonized, the need for a complete vita of the dynasty's founder became apparent. In 1216 Stefan's second eldest son, then Großžupan Stefan Nemanjić, wrote a comprehensive vita. Stefan's Vita shows no appropriations from Vita Savas and is considerably longer, more formal and has a more sophisticated style. It follows the defining Byzantine hagiographies: a rhetorical protologue is followed by a description of the saint's deeds, a sermon ( panegyricon ) and the description of the miracles after his death. Due to the depiction of saints, this second biography was much more popular than the first in the Middle Ages.

Dometijan's complete biography of Savas by a student of Savas from Hilandar Monastery was written no later than 19 years after Sava's death and possibly ten years earlier. It is dedicated to King Stefan Uroš I , who may have commissioned it. It includes longer excerpts from the Scriptures, and underlines the prophecies and unearthly events in Sava's life. Domentijan's style is an early example of a new style of hagiographic and panegyric texts in Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages: a decorated and rhetorical style with a tendency to interweave narrative and theological aspects. The factual thus only occupies a minimum. It thus becomes a timeless narrative with a transcendental level. Teodosijes Vita Savas was largely based on Domentija's report, but as a later author he used a completely different style: he tells lively and entertainingly and is more interested in psychological motives. This also made his vita more popular.

Basically, the Viten give important details about Sava's flight to Mount Athos, the arrival of Stefan Nemanja as monk Simeon, the founding of Hilandar, Sava's move to Constantinople to the Evergetis monastery , the request for the autocephaly of the Serbian church to be preserved by the Constantinople Patriarch and his two Trips to Palestine and visits to the early Christian patriarchates in Alexandria , Antioch and Jerusalem .

Climax

When the Nemanjid Empire reached its greatest development in power in the 14th century, the need for a corresponding official historiography that reflected the ideology of the empire grew. For this reason a whole collection of biographies of the Serbian kings of the Nemanjid house and the Serbian archbishops was made. The authors were Danilo and his students. In terms of the history of ideas, they remain true to the two origins, they offer dynastic history, divine grace and blood holiness . As a new element, the biography of the ruler is now also pictorially implemented as a fresco composition in the Mermorial Foundations of the Kings. The “Wurzel-Nemaniae”, a stylized family tree of the Nemanjids in the form of a vine, is moving into Eastern European painting as a new pictorial formula. Even if there is no clear evidence, it is attributed to Danilo II. It can be found in the Gračanica Monastery , in the vestibule of the Patriarchal Monastery in Peć , in the Memorial Church of Stefan Uroš III. Dečanski in the Katholikon of the Visoki Dečani Monastery and in the Matječa Monastery. There are no models for this representation. Hence, it is believed that it came from an idea of Danilo. The members of the dynasty are depicted in the form of a trellis from bottom to top on a vine. Through Christ, the investiture is carried out on the current ruler on top.

The glorification of the ruler from political and religious cult texts led to visual glorification in the frescoes of the memorial churches . Icons are also designed according to the textual models. The icon with the large depiction of Stefan Uroš IV. Dečanski's zographer Longins is decorated with scenes from the life of Grigory Camblak. The third element corresponds to the popular Serbian heroic epics of Deseterac , which are widespread in a high artistic level , the existence of which is already indicated by Svetozar Koljević in text passages in Sava's biographies in Domentijan and Teodosijes. In the Byzantino-Slavic culture, only the Serbs possessed the full spectrum of political rulers. Only in this way was it possible for the Serbs to develop the only endogenous monarchy in southeastern Europe after the end of Ottoman rule .

Late phase

After the Nemanjid line died out, the rulership biography was transferred to Prince Lazar and his son Stefan Lazarević . With the vita of the despot Stefan Lazarević through the Bulgarian émigré Konstantin Kostenec , the dominance of the vitae began as a historical source, to the detriment of their function as a testimony to the spiritual world of old Serbia. It was the very end of the genre. Gregorij Camblak's heychastic biography Stefan Uroš III. Dečanski stands a bit apart from the old Serbian rule hagiographies.

literature

Source editions

- Stanislaus Hafner: Old Serbian ruler biographies . Volume 1: Stafan Nemanja after the Vites of St. Sava and Stefans the First Crowned. Styria, Graz 1962.

- Stanislaus Hafner: Old Serbian rulers' photographs . Volume 2: Danilo II. And his students: The royal biographies. Styria, Graz 1976.

- Maximilian Braun : Description of the life of the despot Stefan Lazarević from Constantine the Philosopher . In the excerpt, ed. u. trans. by Maximilian Braun. Mouton, Wiesbaden 1956.

- Константин Филозоф: Житија деспота Стефана Лазаревића . Prosveta, Srpska Književna zadruga, Stara Srpska Književnost, knj. 11, Beograd 1989, ISBN 86-07-00088-8 .

credentials

- ^ Stanislaus Haffner: Old Serbian rulers' biographies. Verlag Steyr, Graz 1962, p. 13 ff.

- ↑ ibid Stanislaus Haffner, p. 16.

- ↑ Stanislaus Hafner, p. 15.

- ↑ Stanislaus Hafner, p. 15.

- ↑ Stanislaus Hafner, p. 16.

- ^ Dimitri Obolensky: Six Byzantine Portraits. Clarendon, Oxford 1988, p. 122.

- ↑ Dimitri Obolensky, p. 122.

- ↑ Dimitri Obolensky, p. 123.

- ↑ Stanislaus Hafner, p. 17.

- ↑ Frank fighters : ruler, founder, saint - political cults of saints among the orthodox southern slaves. In: J. Peterson (ed.): Politics and adoration of saints in the high Middle Ages. Sigmaringen 1994, pp. 423-445.

- ↑ Stanislaus Hafner, p. 14.