Amsterdam Machsor

The Amsterdam Machsor (also Great Machsor ) is a Machsor (prayer book) for the Jewish holidays and special Sabbaths , which was probably made in Cologne around 1240 . The elaborately designed manuscript is one of the oldest surviving manuscripts of this type in German-speaking countries. In 2017 she was bought by the MiQua for four million euros . LVR-Jewish Museum in Cologne's Archaeological Quarter and the Joods Historisch Museum in Amsterdam were jointly acquired and will in future be exhibited alternately in both cities. In 2019, the original can be seen in Cologne for the first time in over 50 years.

history

The Amsterdam Machsor ( machsor = 'cycle, cycle', pl. Machsorim ) is one of the earliest illuminated Hebrew manuscripts of Ashkenazi origin. It can be assumed that it was used in the medieval synagogue in Cologne on high feast days . In 1424 the Jews were expelled from Cologne and the synagogue served as a Christian chapel from then on; it was destroyed in the Second World War . How the precious manuscript got to Amsterdam is incomprehensible.

A note in the Machsor is known to have been in the possession of the Amsterdam-based printer Feivesh ha-Levi , who goes by the name Uri Phoebus ha-Levi , some 200 years later . This printer and publisher was a grandson of Moses Uri ha-Levi , who was the first rabbi of a Sephardic community in Amsterdam, and thus in Northern Europe. His father Aaron was a cantor in the Portuguese community in Amsterdam. It is uncertain whether Uri Phoebus ha-Levi inherited the Machsor from his father or grandfather, especially since the prayer book documents an Ashkenazi rite and not a Sephardic one. According to the notes in the manuscript, ha-Levi handed it over to the Amsterdam Jewish Community in 1669, from which he had previously separated in an argument. The reason for the dispute may have been that Ha-Levi insisted on special rights that had previously been granted to his Ashkenazi family by the Sephardic community. In order to be reconciled with the congregation, he gave the Machsor to them .

In the Amsterdam community the book was used on festive days until World War II. The first scholar to study the Machsor scientifically was Isaak Maarsen (born February 27, 1892 in Amsterdam ; died July 23, 1943 in the Sobibor extermination camp ) in the 1920s . It was he who suspected the origins of the manuscript in the Rhineland.

From 1955 the Machsor was on permanent loan in the Amsterdam Joods Historisch Museum ; in Cologne it was shown in 1963 as part of the exhibition Monumenta Judaica - 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine .

In the 2010s it was offered for sale by the Jewish Community, which needed funds to build the National Holocaust Museum in Amsterdam opposite the Hollandschen Schouwburg . The condition for the sale was that the Machsor goes into public hands . In the Netherlands, the manuscript, which despite its eventful long history is in excellent condition, has been on the list of cultural assets worth preserving since 1988.

description

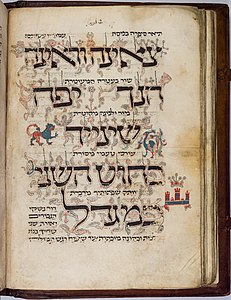

The Machsor is 47.5 by 34 centimeters in size, around eight centimeters high and consists of 331 bound leaves of veal parchment . The cover is made of leather and has two copper clasps. The leaves are elaborately designed with multi-colored borders, luminous ornaments and gold-plated initial words . The book contains the liturgies for Rosh Hashanah , Yom Kippur , Purim , Passover and Shavuot . In addition, chants and prayers from the Tanakh that were recited on the high Jewish holidays are written down. Machsorim, with whose help the cantor conducted the public prayers in the synagogue, were mainly in use in the Jewish communities in the area of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation , predominantly from the middle of the 13th to the middle of the 14th centuries. The Machsor contains comparatively few common prayers, but mainly liturgical poetry ( pijjutim ), in which it differs significantly from the prayer books of the time. These hymns come from the pen of Simeon bar Isaac , a Jew from Magenza presumably born in Le Mans , who probably died between 1015 and 1020.

Neither the place of manufacture nor the names of the obviously wealthy client and the scribe are known. The peculiarities of the liturgy laid down in the book speak for an origin from the Rhenish area, for example the lack of a fixed order of penitential prayers for the festival of reconciliation Yom Kippur, a peculiarity of the rite practiced in Cologne. The magnificent illustrations - including lions, griffins , a peacock and a fort - as well as the elegant calligraphy of the Hebrew square script point to the origins of a metropolis, where the scribes demonstrated a correspondingly high artistic level; in the Rhineland at that time only Cologne came into question as such. Cologne is also mentioned in a small note that was added later.

The dating is based, among other things, on the fact that people in this book are depicted with faces. In later times, Hebrew manuscripts in the German-speaking area began to add animal heads to images of people in order not to violate the biblical prohibition of images .

The Machsor's pages were numbered - presumably in the late 19th century - with both Hebrew and Arabic numerals, with some pages left out. Presumably these pages were temporarily in a different location and were only added later. The page with the prayers at the beginning of Yom Kippur is completely missing. Since it was certainly particularly richly illustrated, it was stolen, so the presumption.

Acquisition of the manuscript

In December 2017, the Rhineland Regional Council, together with the Amsterdam Joods Historisch Museum, acquired the Amsterdam Machsor for four million euros from the Amsterdam Jewish Community. On the German side, the purchase was made possible with financial support from the Kulturstiftung der Länder , the Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation , the CL Grosspeter Foundation , the Rheinischer Sparkassen- und Giroverband , the Sparkasse KölnBonn and the Kreissparkasse Köln . The Machsor is to form the heart of the MiQua Museum in Cologne, which is currently under construction and is scheduled to open in 2021. The manuscript will be seen in Cologne and Amsterdam at the turn of the year. There are also plans to create a digital edition of the Machsor , which visitors can leaf through and which also represents the original if it is in the other museum. From September 2019 to January 2020, the Machsor will be shown again in Cologne for the first time since 1963. The exhibition takes place in the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne , as the new Jewish Museum MiQua has not yet opened.

literature

- Albert van der Heide, Edward van Voolen (ed.): The Amsterdam Mahzor. History, liturgy, illumination (= Litterae Textuales ). Brill, Leiden et al. 1989, ISBN 90-04-08971-3 .

- Elisabeth Hollender : Synagogal hymns. Qedushta'ot of Simon b. Isaac in the Amsterdam Mahsor (= Judaism and Environment. 55). Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1994, ISBN 3-631-47670-1 (At the same time: Cologne, University, dissertation, 1993).

- Landsschaftsverband Rheinland (Hrsg.): The Amsterdam Machsor . MiQua. LVR-Jewish Museum in the Archaeological Quarter Cologne, Cologne 2019, ISBN 978-3-96719-001-4 .

Web links

- official website

- Amsterdam Machzor. In: Jewish Cultural Quarter. Accessed December 20, 2017 .

- Amsterdam Machsor returns home. In: Photography Report. December 13, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2017 .

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d Elisa Kaiser: Cologne rite from Amsterdam. Press release of the Kulturstiftung der Länder , December 12, 2017, accessed on December 17, 2017 . (pdf)

- ^ Ezra Fleischer: Prayer and Liturgical Poetry in the Great Amsterdam Mahzor. In: van der Heide, van Voolen (Ed.): The Amsterdam Mahzor. 1989, pp. 26–43, here p. 26.

- ^ A b van der Heide, van Voolen: The Amsterdam Mahzor. 1989, p. 14.

- ^ Van der Heide, van Voolen: The Amsterdam Mahzor. 1989, p. 15.

- ↑ Rosa Boland: Joods Historisch Museum koopt eeuwenoud gebedenboek. In: ad.nl. December 13, 2017, Retrieved December 19, 2017 (Dutch).

- ^ Van der Heide, van Voolen: The Amsterdam Mahzor. 1989, p. 17.

- ^ Jewish Museum: An important handwriting for the Cologne show. In: ksta.de. December 12, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017 .

- ↑ Matthias Hendorf: “Miqua” exhibition: Hebrew document returns after almost 600 years. In: rundschau-online.de. December 14, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017 .

- ↑ Amsterdam Machsor returns home. In: Photography Report. December 13, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c Joods Historisch Museum rejects uniek gebedenboek. In: rd.nl. December 12, 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2017 (Dutch).

- ^ Van der Heide, van Voolen: The Amsterdam Mahzor. 1989, p. 12.

- ^ Ezra Fleischer: Prayer and Liturgical Poetry in the Great Amsterdam Mahzor. In: van der Heide, van Voolen (Ed.): The Amsterdam Mahzor. 1989, pp. 26–43, here p. 28.

- ^ Hollender: Synagogal Hymns. 1994, p. 19 f.

- ^ Gabriella Sed-Rajna: The Decoration of the Amsterdam Mahzor. In: van der Heide, van Voolen (Ed.): The Amsterdam Mahzor. 1989, pp. 56-70, here p. 69.

- ^ Van der Heide, van Voolen: The Amsterdam Mahzor. 1989, p. 16.

- ↑ Christiane Twiehaus: Back in Cologne after 800 years! In: miqua.blog. December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017 .

- ^ Sven Felix Kellerhoff: Amsterdam Machsor: Cologne is getting back a showpiece of Jewish life. In: welt.de . December 13, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017 .

- ↑ Samantha Bornheim: The first big appearance. In: miqua.blog. September 23, 2019, accessed September 24, 2019 .