Eternity clause

The eternity clause or eternity guarantee (even eternity decision ) is in Germany a provision in Art. 79 3 of Para. Basic Law (GG), which takes stock guarantee of constitutional policy decisions. The fundamental rights of citizens, the basic democratic ideas and the republican-parliamentary form of government must not be affected by a constitutional amendment . Likewise, the division of the federal government into states and the fundamental participation of the states in legislation must not be affected. In the same way, human dignity and the overall structure of the Federal Republic as that of a democratic and social constitutional state are protected.

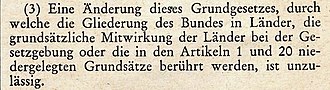

Article 79 paragraph 3 GG reads:

"An amendment to this Basic Law that affects the division of the Federation into Länder, the fundamental participation of the Länder in legislation or the principles laid down in Articles 1 and 20 is not permitted."

With this regulation, the Parliamentary Council wanted to counter the experiences from the time of National Socialism , namely the Enabling Act of March 24, 1933 and natural law principles in the form of human dignity (see Article 1 of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany ) and the structural principles in Article 20 ( Republic , democracy , federal state , constitutional state and welfare state ) provided with an additional security.

For the validity and effectiveness of the perpetual clause, a distinction must be made between the constitution-giver as the pouvoir constituant and the constitution-amending legislature as the constituted state authority that belongs to the pouvoirs constitués . There is a hierarchy between the two: As a constituted state body, the constitution-amending legislature is subordinate to the constitution. He has his competence on the basis of the constitution and only within the framework of the constitution. According to Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law, the legislation is therefore bound by the constitutional order. This results in a hierarchy of norms between constitutional law and a parliamentary law that changes the constitution.

Until the Basic Law is replaced by another constitution ( Art. 146 GG), according to the prevailing opinion today, the eternity clause can not be revoked. With the standardization of an immutability clause, it is implicitly - unwritten - assumed that this clause itself is also immutable.

The term "eternity clause" itself is not in the Basic Law, but rather belongs to the legal colloquial language.

scope

Laws must not interfere with:

- the division of the federal government into states

- the fundamental participation of the federal states in legislation

- the principles set out in Articles 1 and 20

- the protection of human dignity ( Art. 1 para. 1 GG),

- the recognition of human rights as the basis of every human community (Article 1, Paragraph 2 of the Basic Law),

- the binding of state authority to fundamental rights (Article 1, Paragraph 3, Basic Law),

- the federal principle ( Art. 20 para. 1 GG),

- the form of government of the republic ( republican principle ) (Art. 20 para. 1 GG),

- the principle of the welfare state (Article 20, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law),

- the principle of democracy (Article 20 (2) GG),

- the principle of popular sovereignty (Article 20, Paragraph 2, Sentence 1 of the Basic Law),

- the separation of powers (Article 20 (2) sentence 2 GG),

- the binding of the legislation to the constitution (Art. 20 Para. 3 Hs. 1 GG),

- the binding of the executive ( executive power ) and judiciary ( jurisdiction ) to the constitution and other law (Article 20, Paragraph 3, Subsection 2, Basic Law).

These basic principles are beyond the reach of parliamentary majorities . Because the Federal Constitutional Court decides on disputes , this is above the legislature.

According to the wording of Article 79 paragraph 3 GG, only the principles laid down in Articles 1 and 20 GG cannot be changed. The protection of the eternity clause also extends in principle to Article 1 of the Basic Law in all other fundamental rights, provided that these are concretizations of the claim to respect for human dignity. In quantitative terms, this is disputed in detail. In this way the fundamental rights can be changed and they have to meet the requirements of Article 19 (1) and (2) of the Basic Law; However, it is disputed whether the core of a basic right is congruent with the human dignity that is also inherent in it.

Rule of law

Not a single norm, but several provisions of the Basic Law are intended to guarantee that the exercise of all state authority in the Federal Republic of Germany is comprehensively bound by the law ( Article 20, Paragraph 3, Basic Law). Taken together, these principles make up the rule of law in Germany. There are - indirectly also for its validity in Article 28.1 sentence 1 of the Basic Law - in various places other features of the rule of law, for example Article 19.4 of the Basic Law . However, these are not protected by the eternity clause. However, this is controversial.

Right of resistance

The right of resistance guaranteed in Article 20, Paragraph 4 of the Basic Law does not fall under this protection, as it was only later inserted into Article 20 of the Basic Law. This view is hardly controversial among constitutional lawyers today. It is essentially argued that the eternity clause also applies the other way round and does not allow a decision of the constitution- amending legislature to be withdrawn from future changes, whether this be done by systematically adding to Art. 20 GG or by expressly declaring immutability. Because the constitution-amending legislature should not decide where the limits of its power to change lie. This determination by the constitution was made once and lastingly by Article 79 of the Basic Law.

Legal consequences

If such an inadmissible constitutional amendment occurs, unconstitutional constitutional law arises , which is therefore ineffective.

Self-protection of the eternity clause

It is generally assumed that Article 79 (3) of the Basic Law also enjoys the protection of immutability, although it cannot be taken from the wording. The functional interpretation speaks in favor of it, however, because otherwise the protective effect would become meaningless, which would not correspond to the purpose of the norm and the aim of the author. In addition to an immanent justification, over-positive reasons are also represented for the immutability of the eternity clause .

In an essay from 1952, the constitutional lawyer Theodor Maunz recognized what he called the "norm logic" requirement: that Article 79.3 of the Basic Law can only achieve its protective effect if the inviolability that he pronounces for certain constitutional principles , also applies to himself. This means that the justification for inviolability in Article 79.3 of the Basic Law itself is subject to the eternity clause.

However, the eternity clause does not prevent the German people from creating a constitution to replace the Basic Law, even if this brings changes that are actually supposed to be prevented by the eternity clause. This possibility of creating a new constitution is provided for in Article 146 of the Basic Law in both the old and the new version - hereinafter at the most as a total revision of the Basic Law. Some constitutional law experts have assumed, however, that Art. 146 GG old version ceased to be in force with German reunification and that the new version was ineffective insofar as it concerns changes that are inadmissible under Art. 79.3 of the Basic Law. The Federal Constitutional Court considers Article 146 of the Basic Law to be effective, but has expressly left open whether even the constitutional power is bound to the principles protected in the eternity clause "simply because of the universality of dignity, freedom and equality".

Consequences

The eternity clause, for example, is intended to make it impossible to dissolve the Federation while the Basic Law is in force and would obstruct the way to a non- federally organized state - for example based on the French model of a centralized state structure - or the introduction of a parliamentary monarchy based on the model of neighboring Western European monarchies. Such changes require a new constitution for Germany, which invalidates the current Basic Law with legal effect.

European unification

The European integration that goes along with an increasing transfer of powers to the Union level, affected federal, legal and social state, and national democracy as constitutional principles of the Basic Law. The Federal Constitutional Court defined the content of the inviolable constitutional principles in more detail in the Maastricht and Lisbon rulings. For the justification of the European Union as well as for changes to its contractual basis and comparable regulations through which the Basic Law is changed or supplemented according to its content or such changes or additions are made possible, Art. 23.1 sentence 3 GG also refers to the eternity clause of the Article 79.3 of the Basic Law.

The principles of the democratic rule according to Art. 20 Abs. 1 and 2 and Art. 79 Abs. 3 GG, which guarantee the budget right of the parliament as a central element of the democratic decision-making, became with the German approval laws to the contract on stability, coordination and control in the Economic and Monetary Union (SKSV) and the Treaty establishing the European Stability Mechanism (ESMV) called into question; however, the Federal Constitutional Court approved them as constitutional.

See also

literature

- Hauke Möller: The people's constituent power and the barriers to constitutional revision: An investigation into Article 79 Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law and the constituent power according to the Basic Law. Diss., University of Hamburg, 2004 ( PDF ; 831 kB).

- Otto Ernst Kempen: Historical and current importance of the "eternity clause" of Article 79, Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law . In: Journal for Parliamentary Issues 21.1990, pp. 354–366.

- Carl Schmitt : constitutional theory. 1928, 4th edition 1968. (In particular pp. 11 ff., 25 f., 102 ff.)

Web links

- Michael Hein: eternity clauses - never say never! , in: Katapult (May 4, 2015)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Federal Agency for Civic Education : 85 years ago: Reichstag passed Enabling Act , March 23, 2018. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- ^ Dietrich Murswiek : Unwritten eternity guarantees in constitution , University of Freiburg 2008, p. 4.

- ↑ This Josef Isensee : in Christian Hill Gruber / Christian Waldhoff (ed.): 60 years Bonn Basic Law - a successful constitution? , V&R unipress, Göttingen 2010, pp. 135 , 137 .

- ^ Theodor Maunz : Strong and weak norms in the constitution , in: Festschrift for Wilhelm Laforet , 1952, p. 141 (145); Klaus Stern : The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany , Vol. I, 2nd edition 1984, p. 115 f.

- ↑ See Mangoldt / Klein, GG commentary; v. Münch, GG commentary.

- ↑ References in Hauke Möller, The constitutional power of the people and the barriers of the constitutional revision , p. 163 ff.

- ^ Konrad Hesse : Fundamentals of the constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany , margin no. 761.

- ^ So Christian Starck , Verfassungs: Origin, Interpretation, Effects and Safeguarding , Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-16-149916-6 , p. 49 .

- ↑ BVerfG, 2 BvE 2/08 of June 30, 2009, paragraph no. 217 .

- ↑ On this, Horst Dreier , Idea and Shape of the Liberal Constitutional State , Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2014, pp. 273–275 .

- ↑ Carmen Thiele : Stability and Dynamics of the Constitutional Principles of the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany , 2013.

- ↑ BVerfG, judgment of March 18, 2014 - 2 BvR 1390/12

- ↑ Hannes Rathke: Current term Europe : The ESM judgment of the Federal Constitutional Court of March 18, 2014 , German Bundestag / European Department, April 7, 2014.