On overgrown paths

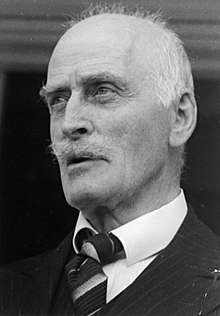

The old work by the Norwegian writer and Nobel Prize winner Knut Hamsun (1859–1952) is on overgrown paths . After the end of the war, Hamsun was charged with collaborating with the German occupation and temporarily admitted to a psychiatric institution. He was only able to return to his estate after three years. He reports on this time, which he perceived as humiliating, in the form of a diary, in which he also settles accounts with the examining psychiatrist, who had assessed him as a person “with permanently weakened mental abilities”.

History of origin

Knut Hamsun, who published an obituary praising the “ Führer ” in a Norwegian daily newspaper after Hitler's death , was placed under house arrest after the end of the war, forcibly placed in an old people's home and charged as a traitor for supporting the German occupation. He was examined for four months in a psychiatric clinic for his mental state and was subsequently fined 325,000 kroner in a trial for his collaboration with the German occupation and for his membership in the Nasjonal Samling , the Norwegian National Socialist party, which made him financially ruined. During these three years he wrote a kind of diary and offered it to Gyldendal Verlag, which had published all of his books by then. The former owner of the publishing house and friend, Harald Grieg, was imprisoned in a concentration camp near Oslo during the war and Hamsun's son Tore ran the publishing house at the instigation of the occupying forces. A falling out had broken out between the former friends. Grieg didn't want to misplace the book. Hamsun tried to publish it abroad, but none of the publishers approached dared to publish it. It was only when the small Swiss publisher “Ex libris” acquired the German-language rights (and granted the license for Germany to List- Verlag) that negotiations with the Gyldendal publishing house got underway. Grieg disapproved of the fact that Hamsun had no regrets in his manuscript. He wanted a later publication; above all, the psychiatrist should not be named. Hamsun remained stubborn, insisted on publication while he was still alive and did not allow any deletions. The book was published on September 28, 1949 in Oslo under the title På gjengrodde stier and at the same time by Bonnier in Sweden with the title På igenvuxna stigar . The first edition of 5000 copies was sold out immediately; a few days later a second edition appeared.

content

Hamsun describes his life from May 1945, when he was placed under house arrest at his manor “Nørholm” near Grimstad , until June 1948; it ends, a month before his 90th birthday, with the sentence: "Midsummer 1948. Today the Supreme Court has ruled and I will stop writing." During this time, he is waiting for his trial, but initially gets sick, although he is not sick is forcibly quartered in a hospital, then in an old people's home, then in a mental hospital for four months and finally he goes back to the old people's home. When the compulsory administration of “Nørholm” is lifted after the end of the trial, he returns to his estate.

These years pass monotonously. Hamsun describes his everyday life and tells associatively events from his past life. He writes: “It is trivial that I write about and it is trivial that I write at all. How can it be otherwise? I am a prisoner on remand (...) All prisoners have to write about the ever-repeating daily events and wait for their verdict. ” When he needs new shoes, for example, it is not possible for him in the hospital to take the letter home with the Please to be able to throw new shoes in a mailbox. The nurses regularly spill the soup and coffee on the tray they bring him his food on. “That's the way it should be, I deserve it,” he thinks and dries the soaked post in the sun. “But it's a shame about the three sisters, young and pretty as they are, but so badly brought up.” The encounter with the traveling preacher Martin, whose unhappy love story is presented in detail, plays a special role. After the hospital stay, the forced admission to psychiatry with humiliating and undignified examinations takes place. “Professor Langfeldt was able to do whatever he wanted with me - and he wanted it a lot.” He leaves the clinic as a sick man, becomes depressed. He complains about the briefing in a long letter to the attorney general. The treason charges will be dropped and a new charge will be brought against his membership in the Nasjonal Samling . The court date is repeatedly postponed. “Would it be possible to speculate on my age and wait for me to die on my own?” He writes at one point. He is almost deaf and his eyesight is deteriorating more and more. Then, after three years, the trial finally takes place. The minutes of Hamsun's defense speech are reproduced in the book.

Quote

- “It is February 11th, 1946.

I'm out of the institution again.

That doesn't mean I'm free, but I can breathe again. In fact, breathing is the only thing I can do for the time being. I am very down. I come from a healthcare facility and I am very down. I was healthy when I got in. "

Structure and language

The book is designed as a kind of diary. But it is “neither a diary nor a story, neither a report nor a confession in the narrower sense. It is a kind of book of hours, ” writes Eberhard Rathgeb and believes that the form is unprecedented in literature. The literary scholar Heinrich Detering also thinks: "It is impossible to determine one's genre [...] all of this is strangely interwoven and left open." In contrast to earlier works, the language is easy to read, the text fluent. But Hamsun knows how to add small ironies to his sentences with great skill. What at first looks like an "indiscriminate hodgepodge of experiences, reports, confessions and narratives, turns out to be an artistic cocoon of wisdom and truth, of prosaic self-confidence and poetic worldly humility" .

Analysis and literary significance

One can draw a connection from Hamsun's first important book Hunger to this last work On Overgrown Paths . In both books the protagonist stands there in poverty and unhappiness, both have reached the end of their journey. “On overgrown paths, that is, the paths that were once laid out are not so important and can hardly be recognized.” The Hamsun biographer Walter Baumgartner writes: “The novel is Hamsun's last stroke of genius and rogue.” Hamsun seems to leave all humiliations behind roll off. When asked during the psychiatric examination what the difference between a child and a dwarf is, he replies: "The age". The psychiatrists only see an intellectual deficit and do not even notice Hamsun's irony and wit.

The book is not a pure factual novel. If you read it, for example, it seems that Hamsun has always been imprisoned during these three years. In reality, he is after being discharged from the psychiatric - he not be forced under management was allowed to return good - was a stranger in a retirement home. “In the course of time the book has developed an existence of its own, regardless of its origins in historical facts.” Hamsun can scoff at himself, his humor sometimes seems a little sad. What is striking is Hamsun's old age, the joy in details, the descriptions of how he is happy about small things and incidents.

In the afterword to the new Hamsun edition, Heinrich Detering draws attention to the “secret inner workings” of the text, to Hamsun's obvious “self-contradictions”. For example, Hamsun writes on the one hand that everything grandiose falls, that this is the course of life; on the other hand, it is human striving to defy fame and immortality. "Every page of this book, a single great artistic effort, testifies to this defiance."

Hamsun and Professor Langfeldt

Above all, the humiliating examination in psychiatry by Professor Langfeldt, which Hamsun describes in his book, had prompted him to write again - a dozen years after his "last" book The Ring Closes. The stay there was torture for him, but he was able to parry Langfeldt's questions in such a way that it was impossible to declare him insane. He refused to answer any questions about his sexuality. Langfeldt therefore had Hamsun's wife Marie , who was already in prison for collaboration, brought to his clinic for an interview. He got her to tell everything about her marriage in return for an assurance of confidentiality. Hamsun saw this as treason and then wanted nothing more to do with his wife. Langfeldt's examination verdict was that he considered Hamsun "for a person with permanently weakened intellectual abilities" . With his last book, in the opinion of almost all book reviewers, Hamsun proved that at almost 90 years of age, he had not lost any of his intellectual powers. The leading Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten wrote: “You don't have to read many pages in the book to realize that it was not written by a senile person.” For Hamsun this was a satisfaction; he had demonstrated his intellectual capacity and worked tenaciously to bring this defeat to Professor Langfeldt. The press response to the results of the investigation was so clear that Langfeldt refrained from filing a lawsuit against the publication of the book, which the publisher feared.

reception

The entire first edition of the book was sold out on the day of publication. The publication "gave rise to hundreds of newspaper articles, book reviews, letters to the editor and editorials across Scandinavia" and was controversial; some thought it was brilliant, others didn't like the fact that a Nazi supporter was allowed to speak for the first time in this way. Above all, Hamsun's self-righteousness was contradicted, and that there was hardly any talk of guilt and atonement. “Most of the reviewers used their columns to resume the poet with grace. […] In all seriousness, the Norwegian public was hammered into a split into 'poet genius' on the one hand and 'political idiot' on the other. "

Based on the book, the film Eiszeit was made under the direction of Peter Zadek in 1975 , in which OE Hasse plays the character of the aged poet. In the film biography Hamsun by the director Jan Troell (1996) Knut Hamsun (played by Max von Sydow ) is shown writing On Overgrown Paths . Per Olov Enquist wrote the script based on Thorkild Hansen's book The Trial against Hamsun .

Voices about the work

The German-Jewish writer, editor and publisher Max Tau (after reading the unpublished manuscript):

- “I couldn't believe that after all that he had suffered, a man his age, handicapped by deafness and blindness, was even able to write like this. Because a magic emanated from the manuscript, which again revealed the full wealth of his creative powers. "

The poet and essayist Gottfried Benn :

- "This book is sweet and silly like many of his books, philanthropic and at the same time cynical, you can't take any of his sentences very seriously, and apparently he doesn't take them seriously either."

The later member of the Swedish Academy Artur Lundkvist after the book appeared in the largest Swedish daily newspaper:

- "Neither age nor misfortune have had anything to do with Hamsun's innate art of style and narrative talent."

The Scandinavian and literary scholar Walter Baumgartner :

- “The book as a whole is once again self-justification - this time not in court, but in a medium that is its very own. This explains the good mood that speaks from this book. Hamsun is by no means bitter, but rather considerate, playful, improvising. And he still knows all the tricks. "

expenditure

German editions

- 1950: On overgrown paths . (Translation: Elisabeth Ihle). Ex Libris-Verlag, Zurich

- 1950: On overgrown paths. A diary . (Translation: Elisabeth Ihle). List, Munich

- 1959: On overgrown paths. A diary . (Translation: Elisabeth Ihle). List, Munich. Paperback: List 123

- 1990: On overgrown paths. A diary . (Translation: Elisabeth Ihle). DTV, Munich (dtv 11177). ISBN 3-423-11177-1

- 2002: On overgrown paths . (Translation: Elisabeth Ihle). DTV, Munich. (dtv 12942). ISBN 3-423-12942-5

- 2002: On overgrown paths. Novel . (Translation: Alken Bruns; Afterword: Heinrich Detering). Knut-Hamsun-Werkausgabe in individual volumes. List, Munich. ISBN 3-471-79466-2

Translations (selection)

The Norwegian edition with the original title På gjengrodde stier was published by Gyldendal in Oslo in 1949. It has since been translated many times, for example: On overgrown paths (English 1967), Grónar götur (Icelandic 1979), Sur les sentiers où l'herbe repousse (French 1981), Se chortariasmena monopatia (Greek 1987), Rohtunud radadel (Estonian 1994 ), Na zarośnie̢tych ścieżkach (Polish 1994), Užžėlusiais takais (Lithuanian 2001), Benőtt ösvényeken (Hungarian 2002), Po zarostlých stezkách (Czech 2002) and Po zaraslim stazama (Croatian 2006)

literature

- Arne-Wigand Baganz: On overgrown paths . In: Versalia. The literature portal review . 2005 (accessed December 2, 2009)

- Walter Baumgartner : An enemy of the people on overgrown paths . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of December 16, 1997

- Heinrich Detering : Afterword . In: On overgrown paths . Munich 2002.

- Robert Ferguson: Knut Hamsun. Life against the current. Biography . List, Munich and Leipzig 1990, ISBN 3-471-77543-9

- Gregor Gumpert: Knut Hamsun's closing words: On overgrown paths . In: Eckart Goebel and Eberhard Lämmert (eds.): Stand for many by standing for yourself. Forms of literary self-assertion in the modern age . Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-05-004007-6

- Thorkild Hansen : Knut Hamsun and his time . Langen Müller, Munich and Vienna 1978, ISBN 3-7844-1875-9

- Aldo Keel: Knut Hamsun and the Nazis. New sources, new debates . In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung of February 9, 2002

- Burkhard Müller : Wet mail for a war criminal . (Review). In: Süddeutsche Zeitung of August 30, 2002

- Eberhard Rathgeb: Cocoon of wisdom and truth . (Review). In: "Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung" of October 21, 2002

- Frank Thiess : Hamsuns “On Overgrown Paths”. An investigation into the spirit and structure of poetic old age . Publishing house of the Academy of Sciences and Literature , Mainz 1966

- Rüdiger Wartusch: On overgrown paths. Everything floats on the tray . (Review). In: Frankfurter Rundschau of October 19, 2002

Individual evidence

- ^ In: Aftenposten, May 7, 1945

- ↑ Sources of origin: Arne-Wigand Baganz: On Overgrown Paths , Robert Ferguson: Knut Hamsun , Thorkild Hansen: Knut Hamsun and his time

- ↑ Text output. Munich 2002, page 174

- ↑ Text output. Munich 2002, page 20

- ↑ Text output. Munich 2002, page 103

- ↑ Text output. Munich 2002, page 78

- ↑ Text output. Munich 2002, page 52

- ↑ a b Eberhard Rathgeb: Cocoon from wisdom and truth

- ↑ In: Afterword . Text output. Munich 2002, pages 177-178

- ↑ Burkhard Müller in: Süddeutsche Zeitung of June 20, 2002

- ^ Walter Baumgartner in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of December 16, 1997

- ^ Robert Ferguson: Knut Hamsun. Life Against the Current , page 598

- ↑ In: Afterword . Text edition Munich 2002, page 179

- ↑ The official result of the investigation from February 5, 1946 bears the signatures of Ørnulv Ødegård and Gabriel Langfeldt.

- ↑ Sivert Aarflot in Aftenposten . Source: Thorkild Hansen: Knut Hamsun and his time , page 542

- ↑ Thorkild Hansen: Knut Hamsun and his time , page 542

- ↑ Ingar Sletten Kolloen: Hamsun. Enthusiasts and conquerors, narcissus and Nobel Prize winners. Landt, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-938844-15-1 , page 463

- ↑ Max Tau : Despite everything! Life memories . Hamburg 1972. Quoted here from: Thorkild Hansen: Knut Hamsun und seine Zeit , p. 517

- ↑ Gottfried Benn : Letters to FW Oelze . Wiesbaden 1977. Quoted here from: Thorkild Hansen: Knut Hamsun und seine Zeit , p. 546

- ^ Artur Lundkvist in Dagens Nyheter . In: Thorkild Hansen: Knut Hamsun and his time , page 543

- ^ Walter Baumgartner: Knut Hamsun . Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-50543-6 , page 135