Beck Weathers

Seaborn Beck Weathers (born December 16, 1946 ) is an American pathologist from Texas .

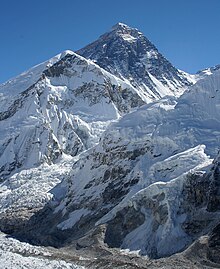

He achieved media attention in 1996 through his special role in the ascent of Mount Everest , which ended in the disaster on Mount Everest (1996) and was captured in a variety of books and films. The best-known works in this context are In icy heights by expedition member and journalist Jon Krakauer , the film In icy heights - Dying on Mount Everest by Robert Markowitz , the film Everest by Baltasar Kormákur and the IMAX documentary film Everest - summit without, based on this book Grace from David Breashears .

Family and profession

Beck Weathers' father was a senior Air Force officer , which is why the family with the military bases moved more often. He attended college in Wichita Falls , Texas. After studying medicine, he joined a successful medical practice and married. He was the father of two children. While on vacation in Colorado , he caught fire for mountain sports. He intended to master the Seven Summits .

Everest

In 1996 Beck Weathers took part in an ascent of Mount Everest, which was carried out by the commercial expedition provider Adventure Consultants under the direction of Rob Hall . On the night of May 9th to 10th, several expedition teams started from Camp IV on the south saddle (7906 m) to the summit.

The difficulties on the mountain began for Weathers at the level of the balcony at around 8,400 meters, when, triggered by the altitude , he developed significant vision problems as a result of an eye operation (radial keratomy ) carried out 18 months earlier . He could no longer perceive everything that was happening more than a meter in front of his field of vision. He admitted this situation to his expedition leader Rob Hall , after which it was agreed that Weathers would wait for Hall to return from the summit. After that, Hall would lead him back down the mountain. The opportunity to descend earlier with other mountain guides or (paying) customers was wasted.

In order to lead the paying customer Doug Hansen , who had just failed the previous year , to the summit, Rob Hall exceeded the self-set reversal time (2 p.m.) by two hours. In the onset of a snowstorm ( including the wind chill factor, around -75 ° C were reached), it was no longer possible for both of them to descend from the summit. Both Hansen and Hall lost their lives that night and the following day, respectively, and thus became two of the eight victims of the tragedy of May 10th and 11th.

In the short term there was hope for Weathers when a group of climbers around Mike Groom tried to take him down to Camp IV, secured with a short rope. This ended in getting lost in a snow storm (whiteout) on the South Col. The group huddled together while Neil Beidleman and Klev Schoening (from the “Mountain Madness” team) used a light clearing of the sky to orient themselves and to reach Camp IV, which is only a few hundred horizontal meters away. A few hours later , the alarmed guide Anatoli Bukrejew helped three of the climbers to Camp IV. Beck Weathers and his Japanese teammate Yasuko Namba remained unconscious. On the morning of May 11th, the other participants decided that there was nothing more to do for the two of them, especially since the climbers would have put themselves in extreme danger if they had to drag the unconscious down the dangerous trail.

Even so, in the late afternoon of May 11th, Weathers managed to get up and run into camp. According to his own statement, it dawned until he saw his frozen right hand right in front of his eyes, which suddenly brought him back to reality.

Weathers was put into sleeping bags in a tent (that of expedition leader Scott Fischer, who was dying further up the mountain ) and again neglected: On the morning of May 12, Jon Krakauer found him still alive, contrary to expectations, and Pete Athans and Todd Burleson, assisted halfway by Ed Viesturs , Robert Schauer and David Breashears , managed to bring him to the astonishment of all on his own feet on the Lhotse flank up to camp II, where now a doctor tent was installed. He jokingly asked expedition doctor Ken Kamler whether he would accept his health insurance.

After the competent initial medical care by Kamler and the Danes Hendrik Hansen, Weathers and "Makalu" Gau Ming-Ho (Taiwan) were led through the Western Cwm to the upper edge of the Khumbu Icefall on the morning of May 13 and carried out in one of the highest helicopter recoveries brought the Nepalese pilot Colonel Madan Khatri Chhetri from the mountain and to Kathmandu. After this spectacular rescue, Weathers had to have his right arm amputated to just below the elbow. All fingers on the left hand also had to be removed. His nose was also amputated and reconstructed from parts of his ear and forehead.

Weathers himself later recalled:

“Initially I thought I was in a dream. Then I saw how badly frozen my right hand was, and that helped bring me around to reality. Finally I woke up enough to recognize that I was in deep shit and the cavalry wasn't coming so I better do something about it myself. "

“I thought I was in a dream. Then I saw how terribly frozen my hand was and that helped me bring myself back to reality. Eventually I woke up enough to realize that I was in deep shit and that the ambulance wasn't coming, so I better do something myself. "

“I was lying on my back in the ice. It was colder than anything you can believe. I figured I had three or four hours left to live, so I started walking. All I knew was, as long as my legs would run, and I could stand up, I was going to move toward that camp, and if I fell down, I was going to get up. And if I fell down again, I was going to get up, and I was going to keep moving until I either hit that camp, I couldn't get up at all, or I walked off the face of that mountain. "

“I was lying on my back in the ice. It was colder than anything you can imagine. I realized I had three or four hours to live, so I started walking. All I knew was that as long as my legs were moving and I could get up, I would be moving towards this camp and if I should fall I would get up again. And if I should fall again, then I would get up again and keep moving until I either reach camp, don't get up at all, or walk over the edge of this mountain. "

Next life

Weathers wrote a book, Left For Dead , which was published in 2000. He is still active as a doctor and motivational psychologist today . He lives in Dallas , Texas.

literature

- Joachim Hoelzgen: Farewell to life . Der Spiegel 9/1998, pp. 156–163 ( article as PDF , 416 kB).

- Beck Weathers with Stephen G. Michaud: Declared Dead: My Return from Mount Everest . Dtv Deutscher Taschenbuch, Munich, 2003, ISBN 3-42324-228-0 .

- Jon Krakauer : To icy heights. The drama on Mount Everest (= Piper 2970). Piper Verlag, Munich a. a. 2000, ISBN 3-492-22970-0 .

- Kenneth Kamler: Doctor on Everest, Emergency Medicine at the Top of the World - a Personal Account Including the 1996 Disaster . The Lyons Press, New York, 2000.

Individual evidence

- ↑ National Geographic Survivors Look Back ( Memento of the original from January 15, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Krakauer: In icy heights. P. 182 f.

- ^ "Left for Dead: My Journey Home From Everest" by Beck Weathers

- ↑ 1996 Everest Disaster Remembered

- ↑ a b Beck Weathers

- ↑ "After the Storm: Into Thin Air Survivors Look Back." ( Memento of the original from January 15, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. - (Weathers looking back at his injuries and misfortune). In: National Geographic , April 2003. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ↑ Ken Kamler, Inside the 1996 Everest Disaster on youtube

- ↑ Peter Potter Field, Helicopter on Everest makes History

- ↑ Krakauer: In icy heights. P. 352

- ↑ Beck Weathers: The Badass of the Week. Beck Weathers. In: The Badass of the Week. Retrieved January 29, 2016 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Weathers, Beck |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Weathers, Seaborn Beck (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American pathologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 1946 |