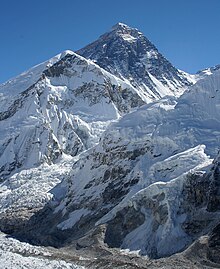

Accident on Mount Everest (1996)

During the accident on Mount Everest on May 10 and 11, 1996, more than 30 climbers were caught by a change in the weather while trying to reach the summit of Mount Everest . Five climbers on the south side and three on the north side of the mountain were killed. Although there are always fatalities when climbing Mount Everest, the events received worldwide media coverage in 1996, because on the one hand several experienced mountain guides from commercial expeditions were among the victims and on the other hand some of the survivors published their experiences in the following period. The reports by the American journalist became particularly well known Jon Krakauer , the British director Matt Dickinson and the Kazakh mountain guide Anatoli Bukrejew . In view of the high number of victims in a single day, the practices of commercially operating organizations on Mount Everest were called into question after the accident.

prehistory

Commercial expeditions

Since the 1980s, climbing the highest point on earth has become more and more attractive. In order to make this ascent possible for less experienced mountaineers, experienced mountain guides founded commercially operating organizations.

Many consider the beginning of this development to be the paid support that mountain guide David Breashears gave entrepreneur and hobby mountaineer Richard Bass to guide him to Mount Everest in the 1985 season - the first time that a largely ignorant amateur has reached the summit of Everest openly "bought". Bass wanted to climb the Seven Summits , and for this he needed success on Everest. This event motivated some very good mountaineers, gave them the idea of offering their experience in organizing expedition ascents against payment to wealthy customers and thus generating a business out of their hobby, which had been a lavish hobby.

These expedition companies organize as much as possible everything for their customers, from entry visas to Sherpas and mountain guides to oxygen bottles for ascent and garbage disposal on the mountain. The paying customers should be led to the summit with a calculable risk and maximum chances of success. Customers range from experienced alpinists to inexperienced mountaineers who (have to) rely more or less blindly on their mountain guides. In addition, the majority of these customers rely on supplemental oxygen to compensate for the effects of thin air at high altitudes and to manage the ascent. About a third of all mountaineers on Everest belong to one of these expeditions. Commercial expeditions on Everest and their approach are under heavy criticism.

Preparing for the climb

Commercial expeditions on Mount Everest follow a scheme: Customers fly to Kathmandu , are received by their mountain guides and then brought in several stages to the respective base camp on the north or south side. Already on the way to the respective base camp, and later also from the base camps, the climbers undertake acclimatization tours for several weeks until they then climb from the base camp to the summit in four to six days, depending on the route . During this time, the climbers carry only minimal personal equipment with them; the rest of the material, from food to gas cookers and sleeping bags to tents, is brought to the individual high camps by Sherpas.

Sherpas also prepare the routes to the summit for customers. This includes the construction of the high camps and the fastening of new fixed ropes at difficult or dangerous points on the ascent. In addition, they take care of the transport of the oxygen bottles. In the spring 1996 season, no climber had reached the summit by May 10th, which is why the key points below the summit were not yet secured with ropes.

Ascent routes from the base camps

The two default routes to the top are those of Tibet outgoing northern route (yellow) and from Nepal outgoing southern route (orange). The first ascent of the mountain took place in 1953 via the southern route. Both routes start at the respective base camp and run over several high camps. The last ascent to the summit begins for the north route in “Hochlager 6” at an altitude of 8,300 m and for the south route in “Hochlager 4” on the so-called south saddle at an altitude of 7,900 m. This last stage is usually covered by mountaineers in a single day without further intermediate camps: They start their ascent at night or in the early morning, climb to the summit and are back in the respective high camps by nightfall. In order to make the way back in daylight, the expedition leaders set a turnaround time in advance of the ascent. When this reversal time is reached, for example 2:00 p.m., the customers then have to stop their ascent and return to the camp, even if they have not yet reached the summit by then.

hazards

Since the summit of Mount Everest is at an altitude of 8,848 m, mountaineers have to climb into the so-called death zone from an altitude of about 7,000 m to reach it . A longer stay is no longer possible in the death zone. The body can no longer regenerate itself even without further exercise. In addition, permanent residence increases the risk of dying from the consequences of altitude sickness , such as cerebral or pulmonary edema. High altitude mountaineers therefore always try to minimize the length of time they spend in the death zone as much as possible.

Other dangers are cold, wind speeds of more than 150 km / h (the summit of Mount Everest protrudes into the jet stream at times ), gusts of wind and sudden changes in the weather.

Although the climbers are surrounded by snow (and rocks), it is very easy to dehydrate your body . Water can be obtained by melting snow, which requires the gas stove and dishes to be taken with you and delays the ascent due to the waiting time when it melts. The mountaineers therefore carry a supply of water with them, which can, however, freeze easily, even if it is carried on the body instead of in a backpack. Dehydration makes the body more susceptible to altitude sickness, which not only affects the physical symptoms, but also the ability to think and make decisions. Climbers suffering from altitude sickness may continue to climb, although it would be safer and more sensible to turn back to camp.

The reversal time is also important: the mountaineers should under all circumstances have reached the high camp again by nightfall on the summit day. Should they not be able to reach the camp in time and therefore have to bivouac above the high camp with insufficient resources , the danger for the climbers increases considerably: On the one hand, for reasons of weight, they usually do not carry tents, gas stoves, sleeping bags and similar things on the Summit stage with you and thus expose yourself to the risk of severe frostbite, on the other hand, the oxygen supplies you take with you are not enough through the night. The lack of oxygen in turn increases the susceptibility to altitude sickness. The descent becomes extremely dangerous at night and due to the exhaustion that has occurred in the meantime.

Another danger is that there are few opportunities to rescue climbers in difficulty from great heights. Most helicopters available cannot hover in thin air, and other climbers generally lack the reserves of strength to help at high altitudes. Mountaineers who cannot descend on their own have to remain lying on the mountain in most cases. The routes on the high slopes of Mount Everest are lined with mountaineering corpses: around 300 people (as of early 2019) have lost their lives trying to climb it.

On the south side

Expeditions

In the spring of 1996 there were several, partly commercial expeditions in the base camp on the south side at an altitude of 5400 m. From there, the mountaineers involved, their mountain guides and the Sherpas climbed within four days over the Khumbu Icefall , the Valley of Silence (“Western Cwm”) and the Lhotse flank to high camp 4 on the south saddle . On the night of May 9th to 10th, the south saddle was the starting point of the following expeditions for the final ascent to the summit:

Adventure Consultants

The New Zealand expedition led by Adventure Consultants , led by Rob Hall , set out for the summit at around 11:35 p.m. on May 9th.

Involved mountain guides:

- Rob Hall ( New Zealand , expedition leader)

- Mike Groom ( Australia )

- Andy Harris (New Zealand)

Customers:

- Frank Fischbeck ( Hong Kong )

- Doug Hansen (USA, experienced mountaineer)

- Stuart Hutchinson ( Canada )

- Lou Kasischke (USA, had climbed six of the Seven Summits )

- Jon Krakauer (USA, experienced mountaineer, but without experience in high altitude mountaineering )

- Yasuko Namba ( Japan , had climbed six of the Seven Summits )

- John Taske (Australia)

- Beck Weathers (USA)

Sherpas (all Nepal):

- Ang Dorje Sherpa

- Lhakpa Chhiri Sherpa

- Kami Sherpa

- Nawang Norbu Sherpa

Krakauer took part in the expedition as a journalist on behalf of Outside Magazine . He was commissioned to write an article about the increasing number of commercial ascents of Everest. In return, the expedition leader Rob Hall was promised advertising space in the magazine.

The Sherpas Arita Sherpa and Chuldum Sherpa stayed in the tents of High Camp 4 on Hall's orders. Their job was to be ready in the event of difficulties. However, both Sherpas contracted carbon monoxide poisoning that afternoon while cooking in the tent.

Mountain Madness

The also commercial expedition of the organizer Mountain Madness was under the direction of Scott Fischer . The participants, like the mountaineers from Adventure Consultants , spent the night in high camp 4 on the south saddle . They left the camp at around 12:05 a.m. on May 10, 1996.

Mountain guide:

- Scott Fischer (USA, expedition leader),

- Anatoly Bukrejew (Kazakhstan) and

- Neal Beidleman (USA).

Customers:

- Martin Adams (USA, had already climbed three of the Seven Summits ( Aconcagua , Denali and Kibo )),

- Charlotte Fox (USA, had climbed all 54 peaks over 4200 m in Colorado and two 8000 m ),

- Lene Gammelgaard ( Denmark , experienced mountaineer),

- Tim Madsen (USA, experienced mountaineer, but without experience on 8000ers),

- Sandy Hill Pittman (USA, had climbed six of the Seven Summits ) and

- Klev Schoening (USA)

Sherpas (all Nepal):

- Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa

- Tashi Tshering Sherpa

- Ngawang Dorje Sherpa

- Ngawang Sya Kya Sherpa

- Tendi Sherpa

The Sherpa "Big" Pemba Sherpa stayed behind in high camp 4 on the instructions of Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa in order to be able to provide help in emergencies.

Customers Dale Kruse and Pete Schoening (both United States) no longer took part in the ascent to the summit. Kruse suffered from altitude sickness and was brought back from High Camp 3 by Scott Fischer to base camp on April 26, 1996, while he was acclimatized, while Pete Schoening, on the advice of the doctors at the base camp, had refrained from climbing higher than to High Camp 3 due to acute cardiac arrhythmias.

Taiwan

On the night of May 10, 1996, the state expedition from Taiwan consisted only of its leader "Makalu" Gau Ming-Ho (Taiwan) and the Sherpas Kami Dorje Sherpa, Ngima Gombu Sherpa and Mingma Tshering Sherpa (all Nepal). Mountaineer Chen Yu-Nan (Taiwan) had an accident on the night of May 9, 1996 in high camp 3 when he slipped and fell into a crevasse . Although he was recovered from the crevice, he died of his injuries that same afternoon.

Makalu Gau set off for the summit shortly after the Mountain Madness group , accompanied by two Sherpas.

Other expeditions

In May 1996, a camera team led by David Breashears (USA) was on the mountain shooting the IMAX film " Everest - Summit Without Mercy ". In addition to Breashears, the team members also included mountaineers Ed Viesturs (USA), Robert Schauer (Austria), Jamling Tenzing Norgay (India, the son of the first climber ) and a few other mountaineers. During the events of May 10th and 11th, the team stayed in High Camps 2 and 3 in the Valley of Silence .

The Alpine Ascents International expedition of Todd Burleson and Peter Athans was also on the ascent between high camp 3 and high camp 4.

Route from the south saddle to the summit

To reach the summit, mountaineers have to climb from the south saddle over the south-east ridge until they have reached the so-called balcony - a small ledge at 8,400 m above sea level. From there the path continues to the south summit about 100 meters below the actual summit, then over a narrow ridge to a 12 m high cliff called Hillary Step . This edge at 8,790 m above sea level is the last major obstacle before the summit and can only be passed by one person at a time on the ascent or descent.

Delays in ascent

On the night of May 10, 1996, a total of 33 climbers set out for the summit. After three hours of ascent, mountaineer Frank Fischbeck was the first to turn back. According to Jon Krakauer, Fischbeck noted “that something was wrong that day” . Fischbeck went down to the camp alone.

The mountaineers from Adventure Consultants and Mountain Madness had instructions from Rob Hall and Scott Fischer to hold together, at least until the teams had reached the balcony at 8,400 m. Hall and Fischer wanted to ensure that the mountain guides always knew where their customers were climbing. At the same time, both expedition leaders failed to announce a fixed reversal time at which all mountaineers on the respective expedition had to break off the ascent and return to camp. In the run-up, both 1:00 p.m. and 2:00 p.m. were discussed as reversal times. The mountaineers involved, however, unanimously report that a final decision was not made. These two factors, among others, played an important role in the following events.

As Krakauer states several times, the instruction to stay together forced fast climbers to wait again and again for the rest of the group. The group of Adventure Consultants , 15 mountaineers after all, mixed up with the Mountain Madness group and the Taiwanese team, which resulted in long traffic jams at key points on the ascent. The climbers waited between 45 and 90 minutes before they could continue climbing. When the leading climbers arrived at the balcony , they discovered that there were no fixed ropes attached to the balcony . The expedition leaders had planned in the base camp that a team of two Sherpas from both expeditions would climb 90 minutes ahead of the customers in order to fasten the ropes, but this was not carried out. The reasons for this can no longer be researched afterwards, as both Rob Hall and Scott Fischer died on the mountain. The climbers were again held up for about an hour until the ropes were fastened. For the climbers this meant not only an hour delay, but also that they had to remain in the cold without moving and cooled down accordingly.

When the first climbers reached the Hillary Step at 8,760 m, they found that the fixed ropes were also missing here. Another hour passed before the mountain guide Neal Beidleman had attached the ropes. In addition, there was a time when the climbers jammed themselves at this key point, which only one person can pass at a time.

Meanwhile, at the end of the traffic jam, the climbers were seriously worried: It was 11:30 a.m. and the summit was still three hours away ascent. Therefore, Stuart Hutchinson, Lou Kasischke and John Taske decided to relegate and turned back. They were accompanied by the Sherpas Kami and Lhakpa Chhiri and reached High Camp 4 at around 2:00 p.m.

At this time Beck Weathers was waiting for help on the balcony after he had problems with his eyes and could no longer see clearly. Rob Hall had told him to wait there until the other climbers came down and could help him.

At 1:07 p.m., mountain guide Anatoli Bukrejew was the first mountaineer of the 1996 season to reach the summit, followed by Jon Krakauer at 1:17 p.m. While Krakauer began to descend after just five minutes, Bukreev stayed on the summit to wait for his customers. In the next 30 minutes Martin Adams and Klev Schoening reached the summit, followed by the majority of the remaining mountaineers. The surviving climbers give the individual times differently, which is why it is difficult to estimate exactly who reached the summit and when it left again. Rob Hall radioed from the summit to base camp and said he saw Doug Hansen and wanted to wait for him. At this point, however, Hansen was only on the Hillary Step, almost 100 meters below the summit. Hansen ignored the Sherpas' requests to turn around and continued to mount, although he was obviously at the end of his tether.

Weather change

On the descent, Jon Krakauer met Martin Adams after a few meters. Adams, an experienced pilot and therefore knowledgeable about the weather, took this opportunity to alert Krakauer to an approaching thunderstorm. The thunderstorm was only recognized later by the other mountaineers, for example by Makalu Gau at 3:10 p.m., shortly after he had reached the summit. Krakauer himself did not notice the full extent of the approaching storm until 3:30 p.m. on the south summit . This covered the mountain in dense clouds from the afternoon onwards, the visibility fluctuated between zero and 150 meters, plus heavy snowfall and strong winds.

Descent in a snow storm

According to his own statement, Anatoly Bukrejew left the summit at around 2:30 p.m. and descended with Martin Adams. At the Hillary Step he met Jon Krakauer and mountain guide Andy Harris, who had to wait there because of climbing climbers until they could abseil. After them followed the mountain guide Mike Groom with the customer Yasuko Namba. The mountain guide Neil Beidleman did not leave the summit until 3:10 p.m. together with four customers. By then, neither Scott Fischer nor Doug Hansen had reached the summit. Both reached him long after the last safe turnaround time: Fischer at 3:40 p.m. and Hansen only after 4 p.m. Even after 4:00 p.m. Rob Hall was still waiting for his customer Hansen at the summit.

At around 3:30 p.m. the leading climbers reached the south summit on their descent , where their paths parted: Anatoli Bukrejew quickly dismounted, followed by Jon Krakauer, while Andy Harris stayed at the south summit. Martin Adams' path is unclear, but he was discovered by mountain guides Mike Groom and Yasuko Namba in the twilight at around 5 p.m. on the north side below the balcony and sent back on the right path. At the same time, Anatoly Bukreev reached high camp 4. The reasons for his rapid descent without waiting for his customers have been controversial ever since. He himself stated that he wanted to be ready to come to the aid of other climbers with hot tea and new oxygen; he had also agreed this with Scott Fischer.

At 7.15 p.m. Martin Adams met Jon Krakauer about 70 meters above high camp 4. Both reached the camp at 7:30 p.m. (Adams) and 7:45 p.m. (Krakauer). However, Krakauer thought Adams was Andy Harris and thought he was safe when he saw him reach the camp while the real Harris was still on the south summit. Since this misunderstanding was only cleared up weeks after the expedition, Krakauer blamed himself for being partly responsible for Harris' death. At the same time, mountain guide Anatoly Bukrejew went in search of the other mountaineers and climbed about 200 meters in altitude, but found no one. He returned to high camp 4 between 8:00 p.m. (according to Bukrejew) and 9:00 p.m. (according to Krakauer).

Further up, at 6:45 p.m., the mountain guides Neal Beidleman and Mike Groom had teamed up with the Sherpas Tasi Tshering and Ngawang Dorje to attract a larger group of customers (Klev Schoening, Tim Madsen, Charlotte Fox, Sandy Pittman, Lene Gammelgaard, Beck Weathers and Yasuko Namba) from the mountain. The group was only 10 to 15 minutes away from Jon Krakauer when the storm rapidly worsened and the group lost their view. Krakauer speaks of a visibility range of six to seven meters at this point in time. Due to the poor conditions and his extremely exhausted customers (Namba and Pittman had already collapsed and had been put back on their feet with medication), mountain guide Beidlemann tried to lead the group on a technically easier route in an arc to the camp. The group reached the south saddle at around 7:30 p.m. , but did not find the camp on the several hectares of land in the storm. The climbers were eventually forced to crouch together and wait for the storm to subside. Around midnight, the storm cleared far enough and the team could now see the camp just 200 m away. Neal Beidleman, Mike Groom, Klev Schoening and Lene Gammelgaard tried to reach the camp with the two Sherpas. Tim Madsen and Charlotte Fox stayed with the extremely exhausted Yasuko Namba, Sandy Pittman and Beck Weathers to call helpers to them. In the camp, Neal Beidleman and Klev Schoening sent the mountain guide Anatoli Bukrejew on a search. Bukreev found the abandoned climbers about an hour later and led Sandy Pittman, Charlotte Fox and Tim Madsen back to camp. Beck Weathers and Yasuko Namba, who both appeared to be dying, were left behind.

Stragglers

The climbers, who had missed the reversal point and were still on the mountain as a result, were now in massive difficulties: Scott Fischer had not reached the summit, where Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa was waiting for him, exhausted until 3:40 p.m. and at 3:55 p.m. Leave clock together with the Taiwanese expedition. Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa stayed back briefly to help Rob Hall and Doug Hansen. He brought both climbers from the summit to just above the Hillary Step and then hurried after his boss Scott Fischer. While descending, he came across mountain guide Andy Harris at around 5:00 p.m. at the south summit and spoke to him briefly. Harris then rose again with fresh oxygen bottles and tried to reach Hall and Hansen above the Hillary Steps . The further events of this group up to the radio message from Rob Hall at 4:43 a.m. on the morning of May 11, 1996 are unknown.

Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa overtook the Taiwanese expedition on the descent and reached Scott Fischer around 6:00 p.m. He tried now to help Scott Fischer by all means with the dismount. Among other things, Fischer is said to have slipped down the slope on his pants. However, Scott Fischer finally got stuck above a technically difficult point at an altitude of 8300 m. Lopsang then tried to build him a shelter from the wind. Shortly afterwards, Makalu Gau and his Sherpas also arrived at Fischer and Lopsang's. Makalu Gau, whose condition was similarly critical at the time, also had to stay with Scott Fischer and his windbreak. His Sherpas continued to descend, followed by Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa about an hour later. The Sherpas reached High Camp 4 between 11 p.m. (Sherpas) and midnight (Lopsang).

The next day

Rob Hall survived the night at an altitude of 8,700 m and reported on the radio at base camp at 4:43 a.m. on May 11. He said he was alone on the south summit . According to his statement, Andy Harris had managed to reach him that night, but was no longer with him at the time of the radio call. Doug Hansen also disappeared that night. It's not clear whether Hall meant "disappeared" or "deceased" as the English term "Doug is gone" can mean both. Hall asked for a rescue team to bring him hot tea and full oxygen bottles.

At around 9:30 a.m. on the morning of May 11, two Sherpa rescue teams made their way to the missing climbers: Ang Dorje Sherpa and Lhakpa Chhiri Sherpa tried to reach Rob Hall at the south summit , while Tashi Tshering Sherpa and Ngawang Sya Kya Sherpa together with a Sherpa from the Taiwanese team Scott Fischer and Makalu Gau wanted to save. The Sherpas found Fischer and Makalu Gau on a ledge 400 meters above the camp. Fischer was still alive at this point, but no longer responded to the rescue team and was therefore left behind. Makalu Gau, on the other hand, was in better condition and was able to descend to high camp 4 with the help of the Sherpas. Ang Dorje Sherpa and Lhakpa Chhiri Sherpa continued to attempt to reach Rob Hall on the south summit , but had to turn around about 300 meters below it at 3:00 p.m. The last attempt to save Rob Hall had thus failed.

Rob Hall reported on the radio several times until the afternoon and informed his teammates in base camp that he could not climb and that his hands and feet were frozen to death. Hall spoke with his wife one last time on satellite phone at 6:20 pm. His last words were, “I love you. Sleep well my dear Please don't worry too much. ” Shortly afterwards Rob Hall passed away. His body was found by mountaineers of the IMAX team on May 23, 1996 in a hollow on the south summit .

Between all the bad news of May 11th, a glimmer of hope emerged in the afternoon when Beck Weathers stumbled into the camp on his own at 4:30 p.m. Previously, a team of several Sherpas, led by Stuart Hutchinson, had tried to rescue Weathers and Yasuko Namba. Since Weathers and Namba were unresponsive, it was decided to leave both of them behind. Even so, in the late afternoon, Weathers managed to get up and run to camp. According to his own statement, it dawned until he saw his frozen right hand (he had lost his glove during the night) right in front of his eyes, which suddenly brought him back to reality.

In the late afternoon, Anatoly Bukreev learned from the rescue team that Scott Fischer had been left behind. Bukrejew therefore went out alone again around 5:00 p.m. to save Scott Fischer from the mountain. He reached Fischer sometime between 7:00 p.m. and 8:00 p.m., but by then he was already dead. Bukrejew returned to high camp 4.

Beck Weathers and Makalu Gau were brought after first aid on May 12, 1996 by Todd Burleson and Pete Athans from Alpin Ascents International as well as the IMAX team and the exhausted Sherpas to the edge of the Khumbu Icefall at 6035 m. The icefall, a steep passage in which the glacier ice falls 600 meters from the Valley of Silence and breaks into large blocks, was not passable for the rescuers because of the crevasses and the associated difficulties in climbing over. Colonel Madan Khatri Chhetri of the Nepal Army Air Force therefore carried out one of the highest mountain rescues in history with a Eurocopter AS-350 helicopter and brought both climbers from the glacier to safety.

Both the IMAX film team and the Alpine Ascents International expedition gave up their own summit plans for the time being when they learned of the difficulties further up the mountain. Both teams made their oxygen supplies available in high camp 4 and also tried to come to the aid of the climbers in camp 4 as quickly as possible.

In the months that followed, there was much debate about Anatoly Bukreev's role in the events. Jon Krakauer, in particular, attacked Bukrejew in his article in Outside Magazine and in his book: Krakauer accused Bukrejew of endangering his customers on the one hand by not using additional oxygen during the ascent. Mountain guides should always ascend with oxygen support in order to be able to help their customers as best as possible at all times, without being hindered by the lack of oxygen themselves. He also criticized the fact that Bukreev had descended so quickly and without waiting for his customers, and also attributed this to the fact that Bukreev was physically incapable of staying longer at the summit or at high altitude without oxygen assistance. Bukrejew replied that by not using oxygen bottles from the start, he did not run the risk of suddenly losing part of his thinking and productivity when the additional oxygen supply was stopped. When ascending without additional oxygen, he is a consistently efficient leader for his customers. Regardless of this, he had agreed with Scott Fischer to cancel the decision about the use of oxygen until the summit storm. For this reason, oxygen was brought to high camp 4 for him, which he actually carried a bottle with, but not used, a bottle with regulator and mask during the summit storm. Accordingly, he did not make any statements that he could carry things for customers without oxygen. At the summit he gave his full bottle to Neal Beidleman, whose supply was running low. The quick descent, which was also criticized, had been discussed with his boss Scott Fischer. Bukreev said he wanted to save his strength for any rescues and be ready to rest and come to the aid of the other climbers with hot drinks; further mountain guides are not necessary due to the large number of guides and sherpas still on the mountain. In the late evening, during the night and the next day, Bukreev had enough reserves several times to save other mountaineers - for the most part by himself, since his completely exhausted inmates did not answer his questions for help at the other tents. Bukrejew was able to move up to Scott Fischer again the next day. Krakauer and Bukrejew only settled the dispute in early November 1997, shortly before Bukrejew died on the Annapurna .

Nevertheless, the argument about the use of additional oxygen in high-altitude mountaineering continues, even if mountain guides like David Breashears take a clear stand: “No matter how strong you are, when you climb Everest without oxygen, you are at the limit. You are then no longer able to help your customers. ” And “ There should only be one place for an Everest guide, either with his customers or directly behind them, and he should use bottled oxygen so that he can provide help. " Likewise, Reinhold Messner declared in New York in February 1998: " Nobody should lead on Everest without using bottled oxygen. "

On the north side

The last stage to the summit begins on the north side in high camp 6 at an altitude of around 8,300 m. To get there, the mountaineers first climb in two days from the base camp to the advanced base camp ( “Advanced Base Camp” , “ABC” for short ) at an altitude of 6450 m. From there the route leads to the 7000 m high north saddle (“North Col”) to high camp 4 and further in two daily stages via high camp 5 (7680 m) to high camp 6.

Expeditions

On May 9 and 10, 1996, there were several, partly commercial expeditions in the various camps on the mountain on the Tibetan north side. The expeditions listed below were involved in the events:

Indo-Tibetan Border Police

The expedition of the Indo-Tibetan border guards was in high camp 6 on May 10th. Only six of the more than 40 team members were waiting in camp 6 for the chance to climb:

- Tsewang Smanla,

- Tsewang Paljor,

- Dorje Morup,

- and three other mountaineers from India did not leave the camp until 5:45 a.m. (Tibetan time: 8:00 a.m.), an extremely late time for the start of the summit stage. Your team leader Mohindor Singh (also India) was in the advanced base camp at the foot of the north saddle. The team did not employ any mountaineering Sherpas.

Japanese expedition

There were also three climbers of the Japanese-Fukuoki Everest expedition on the mountain; the climbers Eisuke Shigekawa and Hiroshi Hanada (both Japan) were accompanied by Pasang Kami Sherpa, Pasang Tshering Sherpa and Any Gyalzen (all Nepal). This team did not want to climb the summit until May 11th and was one day behind the Indian climbers in high camp 5.

More expeditions

In addition to the two expeditions mentioned above, there were other expeditions on the north side, including the English film team led by director Matt Dickinson (Great Britain). This expedition was supposed to accompany and film the summit attempt of the English actor Brian Blessed for a documentary for the TV stations ITN and Channel 4.

Route from high camp 6 to the summit

In order to reach the summit from high camp 6, the mountaineers first have to climb over the yellow ribbon , a rocky and steep passage, to the northeast ridge. From there the path leads over three rock steps called First Step , Second Step and Third Step to the summit. The second step in particular , a 40 m high and around 70 degree steep rock step at 8605 m above sea level, is a difficult obstacle. After the third step , the relatively slightly inclined, but long path over the ridge leads directly to the summit.

Ascent and summit

After setting off from high camp 6, the ascent for the Indian mountaineers initially went according to plan. However, when they reached the northeast ridge, the upcoming storm forced three of the climbers to turn back. Tsewang Smanla, Tsewang Paljor and Dorje Morup continued to climb despite the storm and reported at 3:45 p.m. that they had reached the summit. In the meantime, Krakauer and Dickinson and others assume that the three climbers did not reach the summit of Mount Everest, but rather mistook a knoll at about 8,700 m in the poor visibility conditions for the summit. Krakauer and Dickinson state that none of the mountaineers from Adventure Consultants , Mountain Madness, or the Taiwanese expedition saw the Indians on the summit. The Indians also reported the summit in clouds, while the other mountaineers still had a clear view. Shortly after dark, mountaineers who were in the lower camps communicated over the radio that they had seen the glow of two helmet lamps on the Second Step . However, none of the three Indians reached high camp 6. There was no longer any radio contact with them.

The climbers' whereabouts, reactions

On May 11, 1996 at around 1:45 a.m., the two climbers of the Japanese team made their way to the summit together with the three Sherpas despite the strong wind. At around 6:00 a.m., they came across one of the Indians on First Step , probably Tsewang Paljor. At this point Paljor was suffering from severe frostbite, a lack of oxygen and probably also from altitude sickness. Eisuke Shigekawa and Hiroshi Hanada made no rescue attempts. Both later stated that the Indian was not responsive and "looked dangerous". The Japanese team then continued to climb towards the summit. Above the Second Step , the climbers met the other two Indians, who were also still alive. There is no reliable information about their condition, but it appears that both were already unresponsive at this point and were dying. The Japanese team again made no rescue attempts and continued to climb to the summit, which it reached at 11:45 a.m. in a strong wind. In order to be able to judge the effort required for this, one should note that on the south side the Sherpas who were on their way to Rob Hall had to turn around because of the strong wind. On the way back of the Japanese expedition, the Sherpa Pasang Kami Sherpa freed one of the Indian climbers, probably Tsewang Smanla, from some fixed ropes in which he had become tangled. Dorje Morup was already dead at this point. The Japanese climbers could no longer find the third Indian climber on the First Step . His body was only found huddled under a ledge on May 18. Because of his noticeably green shoes, he was given the designation "Green Boots" in driving directions in the following years .

The actions of the Japanese team triggered a worldwide violent reaction, which was fueled by partly false media reports: It was stated that the rescue of at least one of the Indian climbers would have been possible because he was only 100 m above camp 6 . The indifference of Japanese mountaineers was also heavily criticized. Matt Dickinson notes in his book, however, that he saw the Indian himself when he climbed Mount Everest on May 19, 1996 and that the dead climber was not 100 m, but 300 meters and almost 500 m of climbing distance from High Camp 6. Dickinson writes that it took him four and a half hours of strenuous climbing from camp to the specified location. Rescue was therefore difficult, especially because the Indian had to be brought through the steep yellow belt with rescue equipment (which was not available) . Dickinson concludes that a rescue was impossible under the circumstances. However, in later years mountaineers were sometimes rescued above the second step even if there were problems, but in better weather conditions.

analysis

An analysis of the main reasons that led to the accident shows:

- Both commercial expeditions included mountaineers who had no experience with great heights. These mountaineers were barely able to make informed decisions and were therefore dependent on their mountain guides. The mistakes of some mountain guides put the customers at risk; for example, the rapid solo relegation of Anatoly Bukrejew or the late turnaround time of Rob Hall and Scott Fischer were criticized. Jon Krakauer also describes the mountain guide-customer relationship as problematic because, in his opinion, on the one hand, it made customers, even if they were experienced high-altitude mountaineers, rely too much on the mountain guides. On the other hand, according to Krakauer, the problematic relationship put the mountain guides under pressure to bring as many customers as possible to the summit and to ignore certain signs of danger.

- On May 10th, a large number of mountaineers were on the summit stage. In addition, the members of the commercial expeditions were instructed to stay together. As a result, a large group was traveling with relatively short distances, which caused traffic jams at key points, especially on the Hillary Step . This delayed the ascent of most mountaineers so much that many of them did not reach the summit until after the usual reversal time of 2 p.m. This meant that the time to descend in daylight was running out, and the oxygen supplies of some mountaineers were no longer sufficient.

- Jon Krakauer and some well-known mountaineers (e.g. Reinhold Messner, Edmund Hillary or Ralf Dujmovits ) criticize the practice of letting customers ascend with the help of additional oxygen. They argue that the extra oxygen helps climbers who would not be able to make the ascent without this support and may get into trouble once the oxygen supplies run out or if the oxygen equipment fails. Krakauer suggested that oxygen support should only be allowed in emergencies and that it should be completely avoided otherwise. This proposed practice would also automatically reduce the number of climbers on Everest (and other 8,000 peaks) as well as alleviate the problem of pollution from abandoned empty oxygen bottles high up on the mountain. In an interview about the events, the German high-altitude mountaineer and organizer of commercial expeditions, Ralf Dujmovits, said that since 1996 he has refrained from leading commercial expeditions to the high 8000ers such as Everest, Lhotse or K2 . He said that he could not bear the risk at high altitudes, as a mountain guide “... you go to the limit up there. We can no longer do a clean job at this height. And when I can no longer guarantee people's safety, I just have to keep my hands off it. "

- The change in weather in the afternoon played another important role. The timing of the storm was very unfavorable: many mountaineers were already on the summit or the summit ridge and had already used up a large part of their strength. An earlier storm would have forced the climbers to turn back sooner and with greater reserves of strength; that would have had a higher probability of survival.

- In 1996 the commercial expeditions had less experience of Everest expeditions with hobby mountaineers than, for example, ten years later. In 1996 there were 15 deaths on 98 summit climbs. For part of 2006, however, the rate was eleven deaths and around 400 summit climbs. The providers have learned something new: mountain guides today have a better understanding than in 1996 of what their customers need in terms of equipment, oxygen, help from the Sherpas and fixed lines. They collect weather data, have material ready to rescue and care for injured customers and spend a lot of time adapting their summit strategies to the circumstances.

- Problems caused in 1996 the small number of professionals in relation to customers. The service quota for customers by Sherpas is often 1: 1 at large commercial organizers in the summit stage, so every paying customer is accompanied by a Sherpa. This enables a performance-individual climbing pace - it was one of Krakauer's criticisms to have been slowed down by Rob Hall's stipulation that the group had to stay together for reasons of overview and safety. Beck Weathers, who did not make it to the summit, lost his health for the same reason - when he had visual problems he could have descended with individual supervision instead of having to wait for the others to return to the summit at Hall's behest. Communication is also better today because every team member can have a radio.

- In May 2004, the physicist Ken Moore, together with the physician John L. Semple, published an analysis of the weather conditions of May 11, 1996 in New Scientist Magazine and showed that high wind speeds (due to the effect of hydrodynamic pressure ) reduce air pressure and thus oxygen partial pressure . At the time in question, the effect described could have reduced the oxygen partial pressure by up to 6%. This made the climbers more susceptible to altitude sickness.

List of victims

| Surname | nationality | expedition | Place of death | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rob Hall (mountain guide) | New Zealand | Adventure Consultants | South summit, 8750 m | frozen to death |

| Andrew Harris (mountain guide) | Southeast ridge, 8800 m | lost | ||

| Scott Fischer (mountain guide) | United States | Mountain Madness | Southeast ridge, 8300 m | Exhaustion, frozen to death |

| Doug Hansen (customer) | Adventure Consultants | South summit, 8750 m | ||

| Yasuko Namba (customer) | Japan | South Col, 7900 m | ||

| Tsewang Smanla | India | Indo-Tibetan Border Police | Between first and second step | |

| Dorje Morup | ||||

| Tsewang Paljor |

- Source: 8000ers

Some of the bodies of the deceased are still in the permafrost on Mount Everest. The corpse of Tsewang Paljor served under the name Green Boots (English: "green boots", due to its neon green mountaineering boots) as a landmark on the way to the summit via the north route ( picture of the dead in 2010 ).

Film adaptations

- To icy heights - dying on Mount Everest . (Original title: Into Thin Air: Death On Everest ) Director: Robert Markowitz, Script: Robert J. Avrech, Bergsteigerdrama, USA / CZ 1997

- Everest - summit without mercy . (Original title: Everest ), director: David Breashears , Stephen Judson, script: Tim Cahill and Stephen Judson, documentary / IMAX short film, USA 1998

- Everest . Director: Baltasar Kormákur , screenplay: Simon Beaufoy and William Nicholson , mountaineering drama / 3D film USA / UK 2015

Opera

- Everest . Opera by Joby Talbot , libretto: Gene Scheer , world premiere: January 30, 2015, Dallas Opera

literature

- The Dark Side of Everest , National Geographic, first broadcast May 1, 2003, with statements by Beck Weathers, Peter Athans, Neil Beidleman, Matt Dickinson, Kenneth Kamler, Cathy O'Dowd (Camp 4)

- Anatoli Boukreev , G. Weston DeWalt: The Summit . Tragedy on Mount Everest (= Heyne books. 1, 40569). Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-453-40569-1 .

- Matt Dickinson: The Other Side of Everest. Climbing the North Face Through the Killer Storm. Three Rivers Press, New York NY 1999, ISBN 0-8129-3340-0 .

- Lene Gammelgaard : The final challenge. How I experienced the tragedy on Mount Everest (= Econ & List 26694 Grande ). German first edition, 3rd edition. Econ-und-List-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-612-26694-2 .

- Joachim Hoelzgen: Farewell to life . In: Der Spiegel . 9/1998, pp. 156-163 ( PDF , 416 kB).

- Jon Krakauer : To icy heights. The drama on Mount Everest (= Piper 2970). Piper Verlag, Munich and others 2000, ISBN 3-492-22970-0 .

- Göran Kropp , David Lagercrantz : Alone on Everest. My dramatic solo expedition to the highest mountain in the world (= Goldmann 15019). Goldmann, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-442-15019-1 .

- Beck Weathers , Stephen G. Michaud: Declared Dead. My return from Mount Everest . dtv Verlagsgesellschaft , Munich 2000, ISBN 3-423-24228-0 .

- Lou Kasischke: After the Wind : 1996 Everest Tragedy - One Survivor's Story . Good Hart Pub, 2014, ISBN 978-1-940877-00-6 , pp. 310 (English).

Web links

- Information portal about Mount Everest (English)

- Mount Everest National Geographic (English)

- Illustrated overview of the southern route (English)

- Mountaineer Ekke Gundelach on the approach of Rob Hall and Scott Fischer In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. May 10, 2006.

- "Inside the 1996 Everest Disaster" (slide show) , Dr. Kenneth Kamler (Alpin Ascents Int. Expedition), YouTube, (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jon Krakauer: In Icy Heights: The Drama on Mount Everest. 2000, p. 216.

- ↑ a b c d e f Joachim Hoelzgen: Farewell to life . In: Der Spiegel . February 23, 1998.

- ↑ a b Report by Makalu Gau ( Memento from June 11, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (English).

- ↑ After the Storm: Into Thin Air Survivors Look Back. ( Memento of January 15, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) - (Weathers look back at his injuries and the misfortune). In: National Geographic . April 2003, accessed November 29, 2011.

- ^ Anatoli Boukreev , G. Weston DeWalt: The summit . Tragedy on Mount Everest . Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-453-40569-1 .

- ↑ Jon Krakauer: In Icy Heights: The Drama on Mount Everest. 2000, p. 373.

- ↑ Jon Krakauer: In Icy Heights: The Drama on Mount Everest. 2000, p. 374.

- ^ A b Ed Douglas: Over the Top. (No longer available online.) Outside Magazine online September 2006, archived from the original April 30, 2009 ; accessed on January 4, 2013 .

- ↑ Richard Cowper: The Climbers left to Die in the Storms of Everest . In: Financial Times . May 18, 1996.

- ↑ a b Oliver Häußler: "We cannot guarantee safety on Everest" . In: Spiegel Online . April 16, 2003. Interview with mountain guide Dujmovits.

- ^ The day the sky fell on Everest . In: New Scientist . No. 2449 , May 29, 2004, pp. 15 (English, newscientist.com [accessed December 11, 2006]).

- ^ Mark Peplow: High winds suck oxygen from Everest Predicting pressure lows could protect climbers. BioEd Online, May 25, 2004, accessed December 11, 2006 .

- ↑ Eberhard Jurgalski : Statistics of the deaths on Mount Everest . In: 8000ers.com , (English).