sherpa

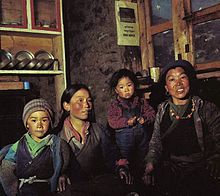

The Sherpa ( Scherpa ; German about "Ostvolk", Tibetan ཤར་ པ Wylie shar pa ) are a people who immigrated 300 to 400 years ago from the cultural region of Kham , mainly today's Qamdo and Garzê , to the central and southern Himalayas is. The name of the people comes from Tibetan : shar means "east", the suffix pa means "people", "people". Members of this ethnic group are also referred to as Sherpa ( plural Sherpas ); the feminine form is Sherpani (plural Sherpanis ). Today there are around 180,000 Sherpas. They live mainly in eastern Nepal as well as in the border regions of China and India . They are mostly Buddhist and mostly speak a language specific to their culture, which is also called Sherpa .

Settlement areas

Most of the Sherpas live in the eastern regions of Nepal. The main area of their distribution is the Solu-Khumbu area , which is made up of the Khumbu , Pharak and Solu regions . They also live in the Rolwaling Valley further to the west and in the Arun and Barun Valley to the east . The Sherpas in the Helambu region north of Kathmandu are less related to them; they come from southern Tibet (“shar” here means east of the Bhote Kosi near Dhunche). In 2001, around 155,000 Sherpas were identified in Nepal by census . The oldest Sherpa village in Nepal, Pangboche , is said to have been built over 300 years ago.

More than 20,000 Sherpas live in India (as of 1997), mainly in the state of Sikkim as well as in the Darjiling district of the state of West Bengal and in the state of Arunachal Pradesh .

About 2,600 Sherpas (夏尔巴 人) live in the People's Republic of China , around 80% of whom speak Sherpa. Although they are not officially recognized as one of the 56 nationalities of China , they have a special status in the Tibet Autonomous Region that is roughly equivalent to "internal recognition". Their settlement area is the administrative district of Xigazê in Tibet, mainly two places directly on the Chinese-Nepalese border: In the large municipality of Zhêntang (陈 塘镇) of the district of Dinggyê (定 结 县) about 1,600 live, in the large municipality of Zham (樟木镇) of Nyalam County (聂拉木 县) approx. 1,000 Sherpas.

Around 1,100 Sherpas live in the United States , almost 500 of them in New York (as of 1998).

history

The origins of the Sherpa are traced back to a group of emigrants who came from Tibet around 1500 and settled in the Solu-Khumbu region. They probably came from an area called Salmo Gang in the Kham region in eastern Tibet. There are various theories about the reasons and more detailed circumstances of emigration, some of which are based on legends. Religious motives could have been just as decisive as knowledge of the fertile valleys of Khumbu. Political unrest is often suspected to be the trigger for the 2,000-kilometer hike. It falls during a period in which the Mongols undertook several military expeditions to Kham; around the same time the ancestors of the later royal family of Sikkim left Kham. Sources suggest that the ancestors of the Sherpa first settled west of central Tibet, near the city of Tinkye south of Lake Tsomo Tretung . From there they are said to have fled an invasion from the west. These are probably the troops of Sultan Said Khan and his general Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat , who had the goal of destroying the city temple of Lhasa and converting the Tibetans to Islam. Based on this thesis, the arrival of the Khamer emigrants in the Solu-Khumbu region can be dated around 1533.

The region was probably completely uninhabited at the time. At most, the extreme south of Solus could have been inhabited by Rai . The group of Tibetan immigrants was divided into four clans , each of which consisted of a small number of families. It may also have been single families. Two of these clans, namely Minyagpa and Thimmi , populated the eastern and western parts of Khumbu. The other two, Serwa and Chakpa , hiked on to Solu. Each of the four clans had a clearly defined area that they claimed for themselves. The number of clan members increased, and small settlements formed the first villages as centers of the activities of the respective clan. Satellite settlements emerged within the clan area, which also grew and later formed independent villages. In the case of the Minyagpa and Thimmi , the spatial separation was accompanied by the disintegration into smaller social units; the clans split up into sub-clans that took on new clan names.

Around the middle of the 18th century, other population groups began to immigrate to the Sherpa area. Some of them also came from Tibet, probably from the Tingri region , some were members of other Nepalese ethnic groups, such as the Gurung , Magar , Newar , Sunwar , Rai , Tamang and the Hindu castes Brahmin and Chhetri , as well as Dhukpa rooted in Bhutan . Some of their descendants adopted the Sherpa way of life. Others founded their own communities, mainly in Solu, without joining the Sherpa society.

During the 19th century, especially during the Rana dynasty in Nepal and the British colonial rule in India , the 5716 meter high Nangpa La mountain pass was used as a trade route between China and India. The Sherpa knew the high path because they used it regularly to exchange salt for grain. In addition, they were genetically adapted to stay at high altitudes and were also trained in handling yaks , which were ideally suited as pack animals for transport across the pass. Therefore, some Sherpas were able to establish themselves as companions of caravans and middlemen in trade. The potato was introduced to Khumbu around the middle of the century . Due to the high effectiveness of the crop, the soil was now able to feed significantly more people and animals than before. It quickly became the staple food in the region and enabled accelerated population growth over the next few decades. At approximately the same time, Sherpas began traveling to the British-controlled Darjeeling to work on tea plantations or building roads. This is where the first records of expeditions into the high mountains come from, for which Sherpas were hired as supporters: in 1907, both the Scottish doctor and mountaineer Alexander Mitchell Kellas and the Norwegians Carl Rubenson and Monrad-Aas recruited Sherpas as porters for their respective ventures. For Kellas it was a climbing holiday, for the Norwegians an ascent to Kangchenjunga up to around 7,200 meters, the highest point an expedition had reached by then. Both groups were impressed by the achievements of the Sherpas and praised not only their physical strength, but also their disposition, behavior and courage. Since then, Sherpas have repeatedly been used as auxiliaries for high mountain expeditions, primarily as porters, but also as mountain guides , scouts or cooks. Within a few years they built a reputation for excellence in the high mountains, especially on Mount Everest . Although foreigners were banned from entering Nepal until the end of World War II , many young Sherpas traveled to Darjeeling to offer their services. Among these was Tenzing Norgay , who on May 29, 1953, together with Edmund Hillary, managed the first ascent of Mount Everest and thus attracted worldwide attention for the Sherpa.

After the occupation of Tibet by China and the flight of the Dalai Lama into exile in India , several thousand Tibetan refugees poured into Solu-Khumbu in 1959. In the meantime, around 6,000 newcomers from Tibet camped in the Khumbu region alone, where around 2,200 people normally lived, many of whom had brought cattle with them. Some of these refugees later returned to Tibet, while others stayed.

Culture and society

Structure of society

The core of Sherpa society consists of a number of clans. Their primary characteristics are exogamy - that is, marriage and sexual contact are only possible with members of other clans - and patrilinearity - that means that children receive the clan membership of the father. The clans consist primarily of the descendants of the four clans who first immigrated to Solu-Khumbu. These original clans are also called "proto-clans" to distinguish them from the clans that emerged from them. About 15 sub-clans emerged from the proto-clans. At around 90%, their relatives make up the majority of the Sherpa. Several other clans are traced back to the Tibetans who immigrated to the Sherpa area from the mid-18th century. These so-called “newer clans” function according to the rules of the other Sherpa clans without any distinction; they are primarily patrilineal and exogamous. In contrast to the other clans, there are no written records of their ancestry, they are almost only widespread in Khumbu and do not see their origins in eastern Tibet.

Towards the end of the 18th century, another part of Pharak society emerged from the descendants of Sherpanis and male immigrants, mainly Chhetri, Dhukpa, Gurung, Newar and Tamang. They were fully integrated into social life and formed clan-like groups. The names of the paternal ethnic origin changed to substitute clan names: There are Chhetri-Sherpa , Tamang-Sherpa etc. These groups also live patrilineal and exogamous, but are not counted among the clans.

On the fringes of Sherpa society are the so-called "Khambas". Kham pa literally means “man from Kham”. However, the term is understood further: it refers to all immigrants from the north within the last generations - that is, from around the middle of the 19th century - who adopted the Sherpa way of life. Most come from the Tibetan regions of Tingri and Gyirong , some from western Nepal. Outwardly they are indistinguishable from the Sherpa and take part in all aspects of social life. However, they do not belong to a clan. This gives them a clear outsider role; the rest of the Sherpa tend to view them as socially inferior. Their reputation rises with the number of generations they have been part of Sherpa society. The term "Khamba" is applied to everyone within the Sherpa culture who does not belong to a clan; Gurung Sherpa or Newar Sherpa are sometimes also referred to as "Khamba".

Population data for Solu-Khumbu from 1965 provide an idea of the proportions of the respective groups in society. Around 30,000 people lived there at that time, about half of whom were Sherpas. Of these, around 13,300 were descendants of the Proto-Clans, around 450 were members of the newer clans, around 350 were Chhetri-Sherpa , Tamang-Sherpa , etc., and around 1,000 were Khambas.

Clans

The Sherpa clans are called ru , which literally means "bones". The parentage in the maternal line is denoted by sha , which means "flesh". This reflects the notion that children inherit father's bones and mother's flesh; only flesh and bones together form a person.

Clans that emerged from the same proto-clan are called brother clans (pingla) . Some of the brother clans still behave exogamously to one another, i.e. do not marry one another.

In the 1960s, the Sherpa became the subject of ethnological research. The Austrian ethnologist Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf and his German colleague Michael Oppitz carried out fundamental scientific work on the development of their society . In his treatise History and Social Order of the Sherpa , published in 1968, Oppitz identified 22 different clans, which he could classify according to their origin from a proto-clan:

| Proto-Clan | Clans |

|---|---|

| Minyagpa | Gardsa, Shire, Trakto, Binasa, Gole, Pankarma, Yulgongma, Kapa |

| Thimmi | Salaka, Khambadze, Paldorje, Gobarma, Lakshindo |

| Serwa | Lama (Serwa) |

| Chakpa | Chawa |

| - (1) | Mende, Chusherwa, Shangup, Nawa, Lhukpa, Sherwa, Jungdomba |

Oppitz thus confirmed a list from Fürer von Haimendorf's 1964 published work The Sherpas of Nepal . The Kapa clan , which Fürer von Haimendorfs did not identify as a separate clan, plays a special role : it is said to have arisen from an illegal marriage. Kapa does not name a work from 2005 either, nor does Shire and Pankarma , instead a clan Magenche (to the proto-clan Minyagpa ) and a “newer clan” called Murmin Tso . In addition, Lhukpa and Nawa are assigned to the proto-clan Chakpa . In contrast, according to Oppitz, "Murmin" is another name for the Tarmang Sherpa .

As early as 1964, Fürer von Haimendorf noticed a tendency among the Sherpa to indicate the number of clans as 18. The difference was explained by the fact that different clans were to be grouped together. Accordingly, the Paldorje and the Salaka are one and the same clan, which is named differently in different regions: Paldorje in Khumbu and Salaka in Solu. In addition, different brother clans would have to be viewed as a unit because their members behaved like members of the same clan in various respects, in particular did not marry one another. This special connection exists between Gole , Binasa and Trakto as well as between Lhugpa and Nawa . Taking these summaries into account, Fürer von Haimendorf put the number of clans in 1964 at 17. He considered this number to be likely given the possibility that one of the former 18 clans could have died out. According to his research, there was only one male member of the Jungdomba clan who lived in Darjeeling . Even today, the number of clans is often given as 18.

language

The Sherpa language goes back to a Tibetan dialect and developed independently for around 500 years from the 15th century. The information on the number of speakers varies considerably. Censuses in 2001 showed that almost 130,000 people in Nepal and around 18,300 in India speak Sherpa as their mother tongue . According to other sources, the total number of speakers worldwide is 86,200 (as of 1994/2000).

Sherpa is a non-written language. A widely accepted convention for textualization does not exist. Therefore it is not possible to translate it into the Latin alphabet . The spelling is usually created - as is the case here - by replicating the spoken sounds and can therefore differ from other spellings.

In addition, many Sherpas speak Nepali as a second language . In Nepal it is around 84% (as of 2001). As far as they were educated in Tibetan monasteries or schools, they learned Tibetan ; Hindi and English are also widely used as second languages among the Sherpas living in India . Exact figures are known from Sikkim, where around 78% of the Sherpas are bilingual or multilingual: Around 62% speak Nepali as a second language, 7% Hindi and 6% English (as of 2001).

Personal names

Sherpas traditionally have one or more nicknames. At birth, they are often named after the day of the week they were born, and religious names are also used. They can also be given another name by a lama in a spiritual ceremony to complement or replace the first one. This can be changed several times in the course of a lifetime. The assignment to a group by a family or clan name as part of the personal name is not common, but many Sherpas use the term "Sherpa" as a surname.

religion

Of the almost 155,000 Sherpas recorded in the 2001 census in Nepal, about 92.8% belonged to Buddhism , 6.2% to Hinduism and 0.6% to Christianity .

Figurative meanings

Ever since British extreme athletes, explorers and adventurers hired men from the Sherpa people as porters in the Himalayas in the first half of the 20th century , the name Sherpa has often been used synonymously for high mountain porters , sometimes without knowing its original meaning. A distinction is made between the high mountain porters or sherpas, the porters who carry equipment and luggage in the (high) mountains to the base camp. The most famous Sherpa Tenzing Norgay (1914-1986), which as an equal companion in 1953 with Sir Edmund Hillary , the first ascent of Mount Everest succeeded.

Derived from this, the chief negotiator of a government is now also referred to as "Sherpa".

Famous sherpas

- Ang Rita Sherpa , 10 ascents of Mount Everest without oxygen

- Ang Tshering Sherpa , President of the Nepal Mountaineering Association (2002–2011) and the Union Asian Alpine Associations (UAAA)

- Dachhiri Dawa Sherpa , Nepalese extreme athlete, Olympic participant

- Kami Rita Sherpa , most ascents of Mount Everest (24 times, as of 2019)

- Lhakpa Tenzing Sherpa ( Appa Sherpa ), second most ascents of Mount Everest (21 times, as of 2011)

- Pemba Dorjee Sherpa , fastest ascent of Everest

- Sardar Tenzing Norgay Sherpa , first to climb Mount Everest

literature

- Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf : The Sherpas of Nepal: Buddhist highlanders . University of California Press, Berkeley 1964, LCCN 64-025908 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed June 17, 2011]).

- Michael Oppitz : History and social order of the Sherpa . In: Friedrich W. Funke (Ed.): Contributions to Sherpa research . Part I. Universitäts-Verlag Wagner, Innsbruck, Munich 1968, ISBN 3-7030-1039-8 ( excerpt online as PDF , approx. 5.7 MB : English Summary. Pp. 143–149 [accessed on June 20, 2011] ).

- Michael Oppitz : Myths and Facts: Reconsidering Some Data Concerning the Clan History of the Sherpas . In: Kailash . Volume 2, 1 and 2, 1974, ISSN 0377-7499 , pp. 121–132 ( online at the University of Cambridge as PDF , approx. 415 KB [accessed June 20, 2011]).

- Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf : The Sherpas transformed: social change in a Buddhist society of Nepal . Sterling, New Delhi 1984, LCCN 84-902892 .

- James F. Fisher: Sherpas: reflections on change in Himalayan Nepal . University of California Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0-520-06941-1 .

- Bernhard Rudolf Banzhaf: Are Sherpas mountain guides? In: The Alps . No. 9 , 2002, p. 53 ff . ( Article online ( memento of September 24, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) on the Swiss Alpine Club's website as PDF [accessed on June 16, 2011]).

- Lhakpa Sherpani: Sherwa mi: There were a lot of stones and little bread. A Sherpa daughter tells . German Foundation for International Development (DSE), Bad Honnef 1994 ( online without pictures (PDF; 456 kB) [accessed on August 18, 2012]).

- Lhakpa Doma Sherpa: Women without a name: The woman in Sherpage society . In: South Asia . tape 21 , no. 1 , ISSN 0933-5196 , p. 38–43 ( as PDF [accessed on August 18, 2012]).

Web links

- Sherpa, the people who are misunderstood as the bearer. Society for Threatened Peoples , Selection Austria, archived from the original on May 9, 2009 ; Retrieved June 20, 2011 .

- Sherpas, the real heroes in the Himalayas , documentation by Otto C. Honegger for sf.tv

- Sherwa mi: Website on the Sherpas of Nepal

Individual evidence

- ↑ Duden . 25th edition. tape 1 . The German spelling, 2009, keyword Sherpa ( online at duden.de).

- ↑ Duden . 25th edition. tape 1 . The German spelling, 2009, keyword Sherpani ( online at duden.de).

- ↑ Fürer von Haimendorf: The Sherpas of Nepal: Buddhist highlanders . 1964, p. 3 .

- ^ A b Government of Nepal. Ministry of Health & Population (Ed.): Nepal Population Report 2007 . ( Document online ( Memento of November 29, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) in .doc format on the Ministry's website [accessed on June 17, 2011]). Nepal Population Report 2007 ( Memento of the original from November 29, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Glenn Collins: Everest, and Sherpas, Are in Vogue; New York's Cool New Guys, Thanks to Books and Films. In: Online edition of the New York Times . April 3, 1999, accessed June 18, 2011 .

- ↑ a b Oppitz: History and social order of the Sherpa . 1968, p. 143 .

- ↑ Fürer von Haimendorf: The Sherpas of Nepal: Buddhist highlanders . 1964, p. 18 .

- ↑ Jamyang Wangmo: The Lawudo Lama: Stories of Reincarnation from the Mount Everest Region . With a foreword by the Dalai Lama . 2nd Edition. Wisdom Publications, 2005, ISBN 0-86171-183-1 , 3. The People of Khumbu: Their History and Culture, pp. 21st ff . (English).

- ↑ Olaf Rieck: The people who came from the east. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on January 25, 2012 ; Retrieved June 20, 2011 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Oppitz: History and social order of the Sherpa . 1968, p. 75 ff .

- ^ Oppitz: Myths and Facts: Reconsidering Some Data Concerning the Clan History of the Sherpas . 1974, p. 122 .

- ↑ Sherry B. Ortner : Sherpas Through Their Rituals . Cambridge University Press, 1978, ISBN 0-521-29216-6 , pp. 18 .

- ^ A b c Oppitz: Myths and Facts: Reconsidering Some Data Concerning the Clan History of the Sherpas . 1974, p. 123 .

- ^ Oppitz: History and social order of the Sherpa . 1968, p. 144 .

- ^ Oppitz: History and social order of the Sherpa . 1968, p. 95, 146 .

- ↑ a b James F. Fisher: Sherpas: reflections on change in Himalayan Nepal . 1990, p. 58 f .

- ^ Robert A. Paul: Sherpa - History and Cultural Relations. In: Countries and Their Cultures. Retrieved June 20, 2011 .

- ^ Eva Selin: Carl Rubenson, Kabru and the birth of the Norwegian AC . In: The Alpine Club (Ed.): The Alpine Journal . 2008, p. 257 ff . ( Article online as PDF , approx. 3.2 MB , on the Alpine Club website [accessed on June 20, 2011]).

- ^ A b Stanley F. Stevens: Claiming the High Ground: Sherpas, Subsistence, and Environmental Change in the Highest Himalaya . University of California Press, Berkeley 1993, ISBN 0-520-07699-0 , Part II, Chapter 9: From Tibet Trading to the Tourist Trade, pp. 357 f . ( online [accessed June 20, 2011]).

- ↑ Stephen Venables : Everest: The Story of Its Exploration . Geo, Frederking and Thaler, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-89405-544-8 , pp. 21, 150 (English).

- ↑ Fürer von Haimendorf: The Sherpas of Nepal: Buddhist highlanders . 1964, p. 28 .

- ↑ a b c Oppitz: History and social order of the Sherpa . 1968, p. 95 .

- ↑ a b c Oppitz: History and social order of the Sherpa . 1968, p. 146 .

- ↑ Fürer von Haimendorf: The Sherpas of Nepal: Buddhist highlanders . 1964, p. 23 ff .

- ^ Michael Oppitz : Myths and Facts: Reconsidering Some Data Concerning the Clan History of the Sherpas . 1974, p. 124 .

- ↑ Fürer von Haimendorf: The Sherpas of Nepal: Buddhist highlanders . 1964, p. 20 .

- ^ Oppitz: History and social order of the Sherpa . 1968, p. 145 .

- ↑ Michael Oppitz : History and social order of the Sherpa . 1968, p. 100 .

- ↑ a b Fürer von Haimendorf: The Sherpas of Nepal: Buddhist highlanders . 1964, p. 19 .

- ↑ Jamyang Wangmo: The Lawudo Lama: Stories of Reincarnation from the Mount Everest Region . With a foreword by the Dalai Lama . 2nd Edition. Wisdom Publications, 2005, ISBN 0-86171-183-1 , Appendix II: The Four Original Sherpa Clans, pp. 319 ff . (English).

- ↑ a b Sherpa History and Facts. (No longer available online.) United Sherpa Association Inc., archived from the original on June 9, 2011 ; accessed on June 17, 2011 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica . Keyword Sherpa ( online [accessed June 17, 2011]).

- ↑ a b Lhakpa Doma Sherpa, Chhiri Tendi Sherpa (Salaka), Karl-Heinz Krämer (Tsak): Sherpa Conversation & Basic Words . S. 4 .

- ^ A b S. Ganesh Baskaran: Linguistic Survey of India . Ed .: Government of India. Ministry of Home Affairs. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Section 3. Sherpa ( online as PDF , approx. 410 KB [accessed June 19, 2011]).

- ↑ Sherpa. In: Ethnologue . Retrieved June 19, 2011 .

- ↑ a b James F. Fisher: Sherpas: reflections on change in Himalayan Nepal . University of California Press, 1990, ISBN 0-520-06941-2 , Note on Orthography and Sherpa Names, pp. XV ff .

- ^ Yogendra P. Yadava: Population Monograph of Nepal . Ed .: Government of Nepal. National Planning Commission Secretariat. Central Bureau of Statistics. Volume I, Chapter 4. Language, p. 164 ( online ( memento of July 23, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) as PDF , approx. 140 KB [accessed on June 18, 2011]).

- ↑ Barbara Pijan Lama: Sherpa Names. (No longer available online.) United Sherpa Association, archived from the original on August 19, 2011 ; accessed on June 17, 2011 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Dilli Ram Dahal: Population Monograph of Nepal . Ed .: Government of Nepal. National Planning Commission Secretariat. Central Bureau of Statistics. Volume I, Chapter 3. Social Composition of the Population: Caste / Ethnicity and Religion in Nepal, p. 133 ( online ( memento of July 23, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) as PDF , approx. 150 KB [accessed on June 18, 2011]).

- ^ Peter Gillman: Everest: eighty years of triumph and tragedy . Ed .: The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 0-89886-780-0 , p. 202 .