Siege of Petersburg

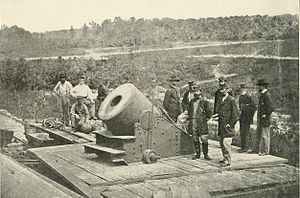

The siege mortar "Dictator" off Petersburg. The person in the right foreground is BrigGen Henry J. Hunt , Potomac Army artillery commander

| date | June 9, 1864 to March 25, 1865 |

|---|---|

| place | Petersburg , Virginia |

| output | Union victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Lieutenant General

Ulysses S. Grant |

General

Robert E. Lee |

| Troop strength | |

|

86,603

|

52,453

|

| losses | |

|

42,000

|

28,000

|

Petersburg I - Petersburg II - Jerusalem Plank Road - Staunton River Bridge - Sappony Church - Reams Station I - Deep Bottom I - Battle of the Crater - Deep Bottom II - Globe Tavern - Reams Station II - New Market Heights - Peebles Farm - Darby Town & New Market Roads - Darbytown Road - Fair Oaks & Darbytown Road - Boydton Plank Road - Hatchers Run - Fort Stedman

The Siege of Petersburg (also called the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign ) was a military operation during the American Civil War that took place from June 9, 1864 to March 25, 1865 east, south, and west of Petersburg , Virginia . The term siege of Petersburg has become common, although Petersburg was neither surrounded by the opposing troops nor cut off from any supplies. Nor did the campaign consist entirely of attacks on Petersburg. After nine months of trench warfare , the Northern Virginia Army could no longer hold its overstretched and thinned lines, which led to the collapse of the front and to evasion during the subsequent Appomattox campaign .

After Cold Harbor , the campaign showed again what it would look like fifty years later in the trenches of the Western Front of World War I.

Strategy and tactics

In 1864, the Lincoln government needed success. Therefore, in March, the President appointed Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant as Commander-in-Chief of the Army. This ordered offensives in all theaters of war. He intended to end the war in November 1864. To this end, he had the two large Confederate armies attacked in particular, in order to prevent them from reinforcing each other and so to smash them. The western wedge aimed through Georgia via Atlanta to the Atlantic coast, the other through eastern Virginia via Richmond , the capital of the Confederation, to the North Carolina border . Both attack wedges were supposed to unite further south and thus end the war. He hired his friend Sherman to carry out the operations in the western theater of war . He himself set up his headquarters 'in the field' with the Potomac Army . From there he was directly involved in the operations of the Potomac, James and Shenandoah armies.

prehistory

In the three-month overland campaign Grant tried again and again to outflank the Northern Virginia Army under General Robert E. Lee on the left, but he never succeeded. The overland campaign ended with the Battle of Cold Harbor on December 3rd - 12th. June 1864.

In early May 1864, the James Army attacked over the Bermuda Hundred Peninsula and intended to attack the fortifications of Richmond. So Lee should be forced to withdraw troops from Cold Harbor. The offensive had stalled by May 20, 1864 at the latest because of the energetic resistance of the southern troops under Beauregard.

Commander

The main players on the Union side were Lieutenant General Grant, Commander in Chief of the US Army, and Major Generals Meade, Butler and Sheridan as Commander in Chief of the Potomac and James Armies and as Commanding General of the Cavalry Corps.

- Commander-in-Chief and Commanding Generals of the Union

Major General

George Gordon MeadeMajor General

Benjamin Franklin ButlerMajor General

Philip Sheridan

While the campaign was still in progress, Grant released Benjamin Franklin Butler from his command and replaced him with Major General Edward Otho Cresap Ord . Grant seldom intervened in the operations of the army commanders-in-chief, but reserved the right to entrust one or the other corps with what he saw as urgent tasks.

The Commander in Chief of the Northern Virginia Army was General Robert E. Lee. General PGT Beauregard made a significant contribution to the defense of Petersburg. Two other important Commanding Generals Lee during the Richmond-Petersburg campaign were Lieutenant General AP Hill and Major General Gordon.

- Commander in Chief and Commanding Generals of the Northern Virginia Army

General

Robert Edward LeeGeneral

P.GT BeauregardLieutenant General

A.P. HillMajor General

John B. Gordon

Terrain and operation plan

The terrain east and south-east of Richmond was dominated by the Chickahominy and James rivers and the swamps between them. The roads leading to Richmond offered opportunities to move around regardless of the weather, while the New Market Heights to the east of the James near Richmond offered opportunities for approach and positioning. The Bermuda Hundred Peninsula between Appomattox and James was partially cultivated. Petersburg was the second largest city in Virginia at the time and a major rail and road hub. No fewer than five railway lines ran through the city and over the Appomattox. The city was protected by several defensive lines in the east and south. The area south and west of Petersburg was criss-crossed by many small watercourses, which could only be crossed on bridges during floods.

On June 5, Grant informed his Chief of Staff Halleck that he intended to conquer Petersburg in order to cut off supplies to the Northern Virginia Army and the Confederate government in Richmond. On June 12, he broke off the Battle of Cold Harbor and tried again to outflank the Northern Virginia Army on the left. Over a 640 m long pontoon bridge and by sea over the York and James to City Point, Virginia, he initially moved the Potomac Army over the James unnoticed by Lee.

Grant's goal was to disrupt the five railway lines. In the first section of the campaign he tried to conquer the city and the railway bridges over the Appomattox. In the further course of the campaign, the Union was to interrupt one railway line after the other. To this end, Grant drew ever further south and west. The soldiers converted the positions they had reached into field fortifications .

Since General Lee had internalized the advantage of defense from field fortifications during the overland campaign, the Northern Virginia Army also erected Grant's field fortifications against the attacking troops.

The campaign was made up of mobile battles at the extreme end of the front and individual frontal attacks from field fortification to field fortification. A trench war raged within the field fortifications .

Initial attacks on Petersburg

First battle for Petersburg (June 9, 1864)

The Bermuda Hundred campaign of the James Army under the command of Major General Butler had stalled shortly after it began. Unconvinced of Butler's military capabilities, Grant compared the position of the James Army to the contents of a corked bottle. Major General Butler was looking for a way to restore his reputation as a political general. He therefore ordered an attack on Petersburg, as this would mean that southern troops would have to be withdrawn from his front and the James Army could again take action against Richmond.

The Confederates had already built strong field fortifications around Petersburg during the peninsula campaign in 1862. The front line received the name of the officer in charge - Dimmock. It was 16 km long and protected Petersburg to the east and south.

On June 8, 4,500 men - two infantry and one cavalry brigade - crossed the Appomattox. The infantry was the Dimmock Line from the east, the cavalry attack simultaneously from the south along the Jerusalem Plank Road. The approach of all brigades was delayed by Confederate field guards. The common attack was thus prevented. After some skirmishing, the infantry commander decided to abandon the attack.

The cavalry encountered a company of Virginia militia with some artillery. The militia consisted of many old and very young soldiers. That is why the battle has been given the name Battle of the Old Men and Young Boys. After almost two hours, the Northern cavalry managed to break through. Meanwhile the southerners had brought battle-hardened replacements from Richmond to Petersburg. The commander of the Northern States cavalry broke off the action and dodged the infantry over the Appomattox.

The Confederate casualties were 75 and the Union 52 soldiers.

Second Battle of Petersburg (June 15-18, 1864)

Grant concealed the abandonment of the Battle of Cold Harbor beginning June 12th so well that General Lee did not believe in another move of the Potomac Army south until June 17th. Grant ordered Butler on June 14th, the XVIII. Corps (his corps) and instructed the commanding general of the corps to attack and capture Petersburg on the same route that the units of the James Army had taken six days before. The strength of the corps was 16,000 soldiers.

Beauregard had 2,200 soldiers under the leadership of Brigadier General Henry A. Wise ', a former governor of Virginia, who he deployed in the northeast of the Dimmock Line. He deployed 3,200 men across from the James Army on the Bermuda Hundred Peninsula. The space between the individual infantrymen in the dimmock line was about ten feet, which was not really acceptable at the time. Smith began the attack by crossing the Appomattox in the twilight of June 15th. The attack was successful and threw the Confederates from the Dimmock Line, about three and a half kilometers wide, back onto another fortification along Harrison Creek. Despite this success, Smith decided not to resume the attack until dawn. The commanding general of II Corps, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock , although known to be of higher rank and aggressiveness, accepted Smith's decision.

In the absence of any instructions from Richmond, Beauregard withdrew 3,200 men from the Bermuda Hundred Front. Butler did not use the James Army as an opportunity to improve his reputation and remained inactive. By the morning of the next day, Beauregard had 14,000 soldiers available in the positions east of Petersburg. Since the IX. Corps Major General Ambrose Everett Burnsides, whom James had crossed, faced 50,000 Union soldiers. Major General Hancock led all three corps into an attack on the field fortifications in the late afternoon. Despite some initial successes, the attacks of the Union troops were repulsed. The three corps dug near the Confederate field fortifications.

On June 17, the Union Corps attacked in an uncoordinated manner. This led to some successes, but mostly ended in the starting positions after counterattacks. Beauregard had the pioneers build new field fortifications west of the Dimmock Line, which the Confederates manned on the night of June 18. General Lee, who had now also recognized Grant's intention, ordered two divisions of Beauregard's troops to be reinforced so that the Confederates had 20,000 soldiers on the morning of June 18.

The Commander in Chief of the Potomac Army reached the area east of Petersburg on the night of June 18 and ordered an attack with four corps at dawn. Completely surprised by the abandonment of the dimmock line, all attacks on the Confederate field fortifications failed. One of the fortress heavy artillery regiments relocated to infantry, the 1st Maine Heavy Artillery Regiment, lost 632 of 900 soldiers. The savior of the left wing of the Potomac Army at Gettysburg , Colonel Chamberlain , was also badly wounded.

Meanwhile, the main forces of the Northern Virginia Army had also reached Petersburg.

After all assault efforts failed, Major General Meade ordered the Potomac Army to build field fortifications. In the four days, the Potomac Army lost 11,386 and the Confederate 4,000 soldiers.

First attacks to interrupt the railway lines

The Southerners served the Northern Virginia Army and Richmond over three railroad lines after last week's attacks. The Richmond and Petersburg railway line between Petersburg and Richmond, the Southside railway line from City Point, Virginia via Petersburg to Lynchburg , Virginia, which east of Petersburg was already used by the Potomac Army and the Weldon railway line , which was used by the last in Confederate The remaining seaport of Wilmington , North Carolina led to Richmond and was closest to the positions of the Potomac Army. Grant ordered a raid to disrupt the Southside Railroad on June 20, and recommended Meade a day later a foray into the Weldon Railroad.

Battle of Jerusalem Plank Road (June 21-23, 1864)

Already on June 20, Meade had the II. And parts of the VI. Corps ordered to cut off the Weldon railway line. Communication between the two corps was lost during the advance on June 21. The divisions of Brigadier Generals William Mahone and Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox from Confederate III met this gap on June 22nd . Corps Lieutenant General AP Hills. The two divisions threw the two Union Corps back to Jerusalem Plank Road and inflicted heavy losses on them.

On the morning of June 23, the 2nd US Corps attacked again, found the field fortifications captured by the Confederates on the previous day abandoned and advanced as far as the Weldon railway line. The soldiers began to destroy the railway line when they were attacked by superior southerners. Since the VI. Corps saw itself unable to support the advance of the II Corps, the corps turned to its own field fortifications.

The damage to the railway line was minor; the Confederates could continue to use them. The field fortifications were extended further south and west. The battle ended in a draw.

Wilson-Kautz Raid (June 22 - July 1, 1864)

Meade hired Brigadier General James H. Wilson to destroy as much of the railway line as possible south and south-west of Petersburg. Grant thought the troop strength was too low and reinforced Wilson's division with Kautz's cavalry division from the James Army . On the morning of June 22nd, 3,300 men and two artillery batteries (12 guns) broke out. They wrecked seven miles of Weldon Railroad tracks at Reams Station and rolling stock. On the same day the two cavalry divisions rode further west and continued the work of destruction on the Southside railway line. On June 23, Confederate cavalry attacked Wilson's rearguard. Kautz and Wilson's divisions dodged west along the railway line, destroying about 30 miles of track. On June 24, the US divisions turned southwest and began to destroy the railway line of the Richmond and Danville railway line.

On June 25, Wilson wanted to destroy the railway bridge over the Staunton. The bridge was secured by around 1,000 Confederate Home Guard from field fortifications and reinforced by artillery. During the battle at the Staunton River Bridge , Kautz's division attacked several times, but was repulsed each time. At the same time, Wilson's rearguard was attacked again by Major General William Henry Fitzhugh Lee's cavalrymen. Despite only minor losses, Wilson and Kautz decided to break off the raid and return to their own line on the Weldon railway line, which, according to Major General Meades, should be in the hands of the Potomac Army.

During the march back, the Confederate cavalrymen were constantly skirmishing with the rearguard of the evasive Union cavalry. To counter the threat, General Lee had tasked Major General Wade Hamptons with intercepting the Union divisions.

On June 28, Wilson and Kautz reached the Weldon Railway 17 miles south of Petersburg. There they met cavalry from Hampton's Cavalry Corps and infantry. In the battle of the Church Sappony they tried to break through, but were blocked. In the evening, Lee's cavalry division also intervened. Wilson and Kautz's divisions managed to escape northwards under cover of darkness.

On June 29, Kautz's division approached Ream's station from the west. However, there was no Union infantry there, but a Confederate division. The first battle developed at Reams Station . The breakthrough attempt of the Union cavalry was unsuccessful, the divisions of Wilson and Kautz were attacked in the flanks by a counterattack by the Confederate. At the request for relief, Meade arranged that both the VI. Corps and parts of Sheridan's Cavalry Corps marched towards Reams Station. When they arrived there that evening, Wilson's and Kautz's divisions had disappeared. These burned their entourage with no prospect of help, rendered the guns unusable and fled south. The northerners did not reach their own lines until July 1st.

As a result of the raid, 60 miles of track had been destroyed; the damage was quickly repaired by the southerners. The losses of the two divisions amounted to 1,445 soldiers. While Wilson assessed this result as a strategic success, Lieutenant General Grant classified it as a near-fiasco .

Operations in late July

Lieutenant General Early's successful raid through the Shenandoah Valley forced Grant to withdraw a corps from the St. Petersburg front in defense of Washington . On July 24th he therefore ordered Major General Meade not to attack the Weldon railway line for the time being. Together with the Commander in Chief of the Potomac Army, he saw no possibility of offensive action.

On June 25, the commanding general of the IX. Corps, Major General Burnside , applied to Meade and Grant to remove a Confederate ledge with a mine below the enemy positions. Both reluctantly agreed, primarily because it kept the soldiers busy. Grant's primary objective was to prevent Lee from sending reinforcements west to reinforce General Johnston in the fight against Major General Sherman . The further the preparations for detonating the mine got, the more Grant and Meade recognized the possibility of a frontal attack on Petersburg.

First Battle of Deep Bottom (July 27-29, 1864)

Grant ordered the Potomac Army with the II Corps Major General Hancocks and parts of the Cavalry Corps under the personal guidance of Major General Sheridan to carry out an advance north of the James . The aim of the operation should be the destruction of the railway bridges of the Virginia Central railway line over the Chickahominy , whereby the II Corps should be the securing of the evasion of the cavalry.

As soon as General Lee learned of the troop movements, he reinforced the troops south of Richmond by a total of 16,500 men from the Richmond Defense District and the positions outside Petersburg. The southerners moved into field fortifications on the southern and eastern edges of New Market Heights.

On July 27, the attack by Sheridan's cavalry east of New Market Heights was repulsed by a counterattack. II Corps confined itself to reconnaissance for the rest of the day. On July 28, Sheridan's Cavalry Corps attacked the Confederate's left flank again. The attack was repulsed again; however, the cavalry managed to capture 200 Confederate soldiers because of their superior firepower. Lieutenant General Grant broke off the operation on the afternoon of July 28th and returned the Cavalry Corps to the Potomac Army, where it was to be used on the left wing.

Grant was satisfied with the outcome of the battle: Although the operation had no effect on Early's operations off Washington, Lee had to withdraw troops from the positions in front of Petersburg in order to respond to the threat at Deep Bottom. Grant therefore saw it as favorable to launch his attack on Petersburg at IX. Corps Major General Burnsides continue to blow up a mine.

Speaking to President Jefferson Davis on the afternoon of July 27, Lee asked Lee to consider whether it was time to cancel Early's assignment. Lee replied, "I don't know how much Early's presence here was more necessary today than it was yesterday."

The Union lost 488 soldiers and the Confederate 679.

Crater Battle (July 30, 1864)

→ Main article: Crater battle

In order to remove a Confederate frontal projection that was up to 40 m from its own positions, the commanding general of the IX. Corps, Major General Ambrose Burnside , dig a 500 m long tunnel under the front ledge. At the end of the tunnel, an explosive charge was to be detonated and the Confederates were to be attacked through the breach. The aim of the attack was to be a crest of a bump about 450 m behind the Confederate positions, from which it was possible to cast directly into Petersburg.

Through the first battle at Deep Bottom, the Northerners succeeded in persuading Lee to withdraw troops from the front in front of Petersburg. Grant therefore set the start of the attack on July 30th. Meade presented the IX. Corps neighboring corps ready to take advantage of a success immediately. A few hours before the start of the attack, both commanders-in-chief ordered Burnside not to deploy the 4th division, which had been prepared for precisely this attack and which consisted of "blacks". While Meade justified this order with a lack of confidence in the capabilities of the soldiers of the IVth Division, Grant later said before the “Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War”: “If the attack fails, that would be said we had sent these people forward and burned them because they were not worthy of us. But you couldn't say that when we sent white troops ahead. "

The explosion took place at dawn and created a crater 10 meters deep, 20 meters wide and 60 meters long. A Confederate infantry regiment and an artillery battery were destroyed in the explosion or buried in rubble. Neighboring Confederate forces fled in fear. The attacking Union soldiers stopped and marveled at the crater. Due to a lack of terrain knowledge, ambiguous orders and a lack of guidance, the commanders led their brigades through the crater instead of leading around the crater into the flanks of the Confederate positions. The following two divisions also followed the example of the front division.

The confusion peaked when Confederate artillery and mortars shot at the crowd in the crater, causing soldiers to flee the crater. However, the refugees had difficulty reaching the rim of the crater without ladders, which added to the chaos. Few officers managed to rally their units and advance on both sides of the crater. However, these units ran into a counter-attack by the Confederates that had begun in the meantime and fled. Around 8:00 am, the units of the colored 4th Division struggled through this mess. They became the focus of the Confederate counterattack under Brigadier General Mahone. As on other battlefields, many Confederate soldiers were very upset by "Negroes" in uniform and murdered many when they tried to surrender.

The IX. Corps lost over 3,798 soldiers - a third of them from the 4th Division - compared to less than half in the Confederate. Meade and Grant blamed all of the blame for this disaster on Major General Burnside and his division commanders. The posts of the commanding general and the division commanders were newly filled. In a message to the Chief of Staff, Major General Halleck, Grant wrote on August 1st: “That was the worst event I witnessed during the war. I have never experienced such an opportunity to take the fortifications and I do not expect another chance. "

Second Battle of Deep Bottom (August 14-20)

Lieutenant General Early burned down on the day of the Chambersburg, Virginia crater battle. In order to support Early in a possible success, Lee ordered an infantry and a cavalry division in the area of Culpeper, Virginia. Grant believed that the entire I. Corps of the Northern Virginia Army had been relocated. Another attack against the 8,500 remaining Confederate defenders Richmond would both prevent further reinforcements from Early and force Lee to withdraw more troops from the positions in front of Petersburg.

Grant assigned the attack to the X Corps under Brigadier General Birney and the II Corps. On the night of August 13th the first outpost skirmishes took place. Birney's Corps failed, however, to take the Confederate field fortifications on New Market Heights. The II Corps reached its starting positions only slowly, with many soldiers dying from heat stroke. Around noon on August 14th there was new fighting. The US generals were surprised to find two Confederate divisions carved across from them . The 2nd US Corps attacked with two divisions on the right. The Confederates were therefore forced to strengthen their positions on the left wing with troops from the right wing. The X. Corps took advantage of this and broke into the Confederate field fortifications and captured four artillery pieces.

Although largely unsuccessful, General Lee was now convinced that the threat east of the James was too great and he moved two infantry brigades and two cavalry divisions, which were intended to reinforce Early, to the area south of Richmond. On August 16, a federal cavalry division attacked on the left flank of the Confederate and fought all day with the cavalry division deployed there by Lee. On the other wing of the Union, the X. Corps attacked and broke Confederate positions with an infantry division. However, the two commanding generals did not use this advantage due to insufficient information and the Confederates succeeded in sealing off the break-in point and regaining their positions.

General Lee planned a counterattack east of the James on August 18th. However, the operation was poorly organized by the local commander and failed. On the night of August 20, the II. Corps moved over the James to its former positions in front of Petersburg and thus ended the battle.

The Union lost 1,899 and the Confederate 1,500 soldiers.

Battle for the Weldon Railway

Grant meanwhile had the VI. Corps from the Potomac Army and the XIX. marched from Louisiana to Washington and saved the capital from being captured by Early. So that the campaign would not be disturbed by Early's further actions, on August 1st he instructed Sheridan to take command of all troops available there and to pursue Early through the Shenandoah Valley and destroy them. To this end, he also released an infantry and cavalry division from the positions in front of Petersburg and placed them under Major General Sheridan.

General Lee had reinforced Early with two divisions during August. When General Lee had to move troops from the positions south of Petersburg because of the second battle at Deep Bottom, Grant ordered another attack to interrupt the Weldon railway line. He hired Brigadier General Governor Kemble Warren's V Corps to carry out the project . As commander of the Confederate General Beauregard and the commanding general of III. Corps of the Northern Virginia Army, Lt. General AP Hill, opposite.

Battle of Globe Tavern (August 18-21)

V Corps marched south at dawn on August 18 and reached the Weldon Railway at about 9 o'clock. While parts of the corps began to destroy the route, two other divisions secured these activities against a possible attack by the Confederates from the north. At noon three Confederate brigades attacked, which Beauregard had scraped together behind the front. The attacks were repulsed after initial success. The V Corps dug into the positions it had reached in the evening.

During the night both opponents strengthened themselves - the V Corps by the IX. Corps, after the replacement of Burnside, now under the leadership of Major General John G. Parkes - the Confederate through two divisions from AP Hills III. Corps. In the late afternoon of August 19, the southerners attacked again unsuccessfully. On the night of August 21, the V. and IX. Corps two miles to catch up with Potomac Army positions on Jerusalem Plank Road. The corps dug in. Another Confederate attack against these positions by 10:30 a.m. on August 21 was also unsuccessful. The Union's losses were 4,279 and the Confederate's 1,600 soldiers.

Through the battle of Globe Tavern, Union forces had succeeded in breaking the Weldon railway line at a key point. The Confederates were forced to reload supplies on wagons in Stony Creek, North Carolina and haul them 30 miles on roads to Boydton Plank Road. This was not viewed as critical by the Confederates. Lieutenant General Grant was not satisfied with the outcome of the battle.

Second Battle for Reams Station (August 25)

Lieutenant General Grant intended to make the Weldon Railroad permanently unusable for the supply of the Northern Virginia Army and therefore ordered a renewed advance south of the Globe Tavern. He entrusted Major General Hancock's II Corps with the implementation, which was reinforced by the last remaining cavalry division of the Potomac Army.

On August 22nd, the cavalry division and one infantry division reached the railroad line and destroyed the route three miles south of Ream's station. On August 23, the next infantry division reached the area and ensured the continuation of the destruction work from field fortifications that had been built during the Wilson-Kautz raid.

General Lee realized that the II Corps had no connection with the positions of the V Corps in the north. He chose to attack the II Corps with strong forces in order to inflict such a significant defeat on the Potomac Army that could have great psychological repercussions for the upcoming presidential election in the north.

On August 25, the southerners, led by Lieutenant General AP Hills, attacked the northerners' positions. After unsuccessful attempts in the morning, the Confederates managed to break through on the right wing of II Corps in the afternoon. At the same time, the Confederate cavalrymen under Major General Hampton overran the defenders on the other wing of the corps. Only after a counter-attack did Major General Hancock manage to return the remaining parts of his corps to St. Petersburg under cover of night. The Union lost 2,602 and the Confederate 814 soldiers.

Catering raid (September 14-17)

On September 5, Major General Wade Hampton learned that five miles east of Grant's headquarters in City Point, Virginia were 3,000 cattle guarded by only 150 men. General Lee had previously suggested that Hampton use opportunities to operate behind the Potomac Army.

On September 14, Hampton rode with 3,000 cavalrymen west and south around the field fortifications of the Potomac Army. Two days later he attacked the federal associations on both sides of the cattle herd and took possession of the herd without major resistance. Hampton started the march back with 2,486 cattle. An attempt by the Potomac Army to retake the herd was unsuccessful. Hampton reached Petersburg with the cattle on September 17th. The supply of the soldiers of the Northern Virginia Army was ensured in the long term.

Attacks in September / October

Battle for New Market Heights (September 29-30)

On the morning of September 29th, the James Army attacked the Confederate defenses north of the James. After the initial successes of the federal forces at New Market Heights and Fort Harrison, the Confederates rallied and sealed off the break-in. General Lee reinforced the forces north of the river and on September 30th attacked unsuccessfully. The James Army dug in and the Confederates built new field fortifications, sparing the lost forts. As Lieutenant General Grant had expected, Lee had released troops from positions south of Petersburg in order to counter the threat north of the James. The Union lost 3,327 and the Confederate about 2,000 soldiers.

Battle of Peebles Farm (September 30th - October 2nd)

Simultaneously with the advance of the James Army, Grant instructed the Potomac Army to attack again on the left wing and cut off other lines of communication of the Northern Virginia Army. Major General Meade commissioned four infantry and cavalry divisions led by Major General Warren to carry it out.

Warren's forces overran the most westerly Confederate field fortifications - Fort Archer - on September 30, and were about to outflank the northernmost right flank of the Northern Virginia Army. On October 1, federal forces fended off a Confederate attack under AP Hill and were able to expand their positions to Peebles and Pegrams farm by October 2. After this limited success, Major General Meade abandoned the operation. Along the line they had reached, the Potomac Army built field fortifications, extending their positions five miles west of the Weldon Railway. The Union lost 2,889 and the Confederate around 1,000 soldiers.

Battle of Darbytown (October 7th)

After the loss of Fort Harrison on September 29 and the ever-increasing threat from Richmond, General Lee launched an attack on the far right flank of the Union forces on October 7. The James Army cavalry deployed on Darbytown Road in front of the field fortifications was routed, and the southerners' attack failed in front of the field fortifications of the X. Corps of the James Army. The two Confederate divisions that had carried out the attack dodged into their field fortifications off Richmond. The Union lost 458 and the Confederate around 700 soldiers.

Skirmish on Darbytown Road (October 13)

On October 13th, the James Army conducted an armed reconnaissance in the direction of Richmond. This was to clarify the exact course and strength of the field fortifications that the Confederates built after the battle for New Market Heights. Most of the time, the field guards only skirmishes with individual scouting parties. The forced reconnaissance of a brigade was turned down by the Confederates with high losses for the James Army. The Union lost 437 soldiers.

Battle of Fair Oaks and Darbytown Road (October 27-28)

Simultaneously with the operations of the Potomac Army on the left wing southwest of Petersburg, the James Army attacked on October 27 with the X and XVIII. Corps took up positions of the southerners in front of Richmond. The attack of the XVIII. Corps at Fair Oaks failed completely, the X. Corps was thrown back to the starting positions after a counterattack by the southerners. The Confederate field fortifications remained intact in their hands. The Union lost 1,603 soldiers.

Battle of Boydten Plank Road (October 27-28)

Boydton Plank Road was a major Confederate supply route and its interruption was a target of the campaign. Major General Hancock was commissioned to first take the Boydton Plank Road and then interrupt the Southside Railroad six miles to the north. For this purpose, the II. Corps by divisions of the V and IX. Corps and the Cavalry Division of the Potomac Army reinforced. On the morning of October 27th, II Corps left its positions, bypassed the Confederate field fortifications far to the south, and advanced successfully north along Boydton Plank Road. Around noon, Major General Meade saw a gap between the II and V Corps. In order to prevent the II Corps from attacking in isolation, he ordered Hancock to stop the attack until a division of the V Corps had established the connection. At the same time, Lieutenant General Grant personally carried out a reconnaissance during which he came under fire and which led to the result that the Confederate field fortifications were too strong. Grant therefore ended the attack.

The II Corps had already crossed Hatcher's Run to the north and suddenly found themselves facing Major General Hamptons Cavalry Corps of the Northern Virginia Army as they dodged south. Cut off from the other Union units, the II Corps was attacked from two other directions. Unlike two months ago at Ream's station, the soldiers of the II Corps did not panic. Hancock ordered an attack on each of the Confederate flanks and forced them, now also threatened with being cut off, to move to Boydton Plank Road. Lieutenant General Grant left it at the discretion of Hancock to remain in the very exposed positions he had reached or to use the starting positions. On the morning of October 28, the II Corps marched back to its starting positions. The Union lost 1,758 and the Confederate around 1,300 soldiers.

The battle was Major General Hancock's last. He gave up command of the II Corps because of the aftermath of his injuries sustained at Gettysburg. His successor as commanding general was Major General Andrew A. Humphreys , until then Chief of Staff of the Potomac Army. At the same time, the Battle of Boydton Plank Road was the last battle of the 1864 campaign. Boydton Plank Road remained in Confederate hands. Both sides spent the winter in winter storage or in the field fortifications. No major operations took place during the winter until the next spring. That didn't mean it was quiet at the front, though. The everyday life of the soldiers consisted of scouting and raiding troops on both sides, constant use of snipers and on the US side constant and regular artillery and mortar fire at the positions of the Northern Virginia Army. In addition, there was a constant increase in desertions among the Confederates, not least because of the ever increasing supply bottlenecks, especially in the case of food. A Confederate captain wrote:

"Our living is now very poor, nothing but corn-bread and poor beef - blue and tough - no vegetables, no coffee, sugar, tea or even molasses ..."

"Life is very poor now, nothing but corn bread and inferior meat - rotten and tough - no vegetables, no coffee, sugar, tea or even molasses ..."

Since June, Lieutenant General Grant had expanded the Union's positions south and south-west of Petersburg further and further west. After the Battle of Boydton Plank Road, they stretched from a point east of Richmond around Petersburg to west of the Weldon Railway for a length of 35 miles. The supply of the Northern Virginia Army was only possible via the Southside railway line and various roads leading from the west to Petersburg and Richmond. Grant had not been able to conquer Petersburg, but had achieved some important campaign goals. General Lee saw the threat to the Northern Virginia Army just as clearly. Speaking to President Jefferson Davis, he pointed out that his own lines were being thinned and that if he were not given reinforcements, they would face great disaster.

Battle of Hatchers Run (February 5-7, 1865)

After a slight improvement in weather, the Potomac Army's Cavalry Division attacked Confederate supply traffic on Boydton Plank Road on February 5, 1865. The V Corps secured the advance against attacks by the Confederates from the north, the II from positions at Hatchers Run against attacks from the west. A division of the III. Confederate Corps attacked Potomac Army's II Corps without success. On February 6, the cavalry division returned unsuccessfully. In the afternoon, major associations of the III. Corps attacked the II and V Corps and threw them back to positions east of Hatchers Run. After reinforcement in the night, the V Corps attacked again on the morning of February 7th and took the crossings over the stream that had been lost the day before. The Potomac Army had extended its field fortifications three miles southwest to the Hatchers Run. The Northern Virginia Army was forced to expand their already thinned field fortifications further west. The Confederate positions stretched 37 miles and were occupied by 46,398 soldiers. The Union lost 1,539 and the Confederate around 1,000 soldiers.

Attack on Fort Stedman (March 25, 1865)

The Northern Virginia Army was more than half that of the James and Potomac Armies by mid-March 1865. Lee also knew that the 50,000 soldiers of Sheridan's Shenandoah Army would soon be reinforcing the Union armies outside Petersburg. He feared that the Northern Virginia Army could not withstand such a superior force in an attack on the right wing and so the last supply line - the Southside Railway - would be severed. The cutting off of the supply line meant not only the encirclement of the Northern Virginia Army, but also the loss of the possibilities of agile operations management. Lee hoped to force Grant to pull strong forces away from his left wing with an attack. He wanted to use this to march with the Northern Virginia Army along the Southside Railroad to the southwest and to unite with General Johnston's Tennessee Army in North Carolina.

In order to achieve this goal, he had withdrawn major formations from his right flank and placed them under the II Corps under Major General John B. Gordon . The attack began with a ruse early on March 25th. First, the Confederates managed to break into the field fortifications of the Union troops. However, the intended fire support for the breakthrough did not materialize; instead, Union artillery sealed off the break-in point. The counterattack by IX began at around 8 a.m. Corps. The Union troops forced the Confederates to move to their starting positions. The Union lost 1,044 and the Confederate about 3,500 soldiers. The battle had no effect on the course of the field fortifications. The losses of the Northern Virginia Army amounted to about seven percent of the total strength, but decisive for the continuation of the war was the weakening of the field fortifications on its right wing.

Result

Grant wanted to conquer the transportation hub Petersburg at the beginning of the Richmond-Petersburg campaign. After two repulsed attacks with heavy losses, the town was no longer the target, but Grant tried to interrupt the various supply lines - rail and road. He succeeded in doing this by the end of March through operations that often took place simultaneously on both wings of the front. Ultimately, only the Southside railroad was available to the Confederates.

Lee strengthened the right wing of his positions at Five Forks - an important crossroads on the way to the Southside Railroad. Grant ordered Sheridan, who had returned from Shenandoah Valley, to attack right there. The Battle of Five Forks was the first battle of the subsequent Appomattox campaign .

The campaign had no political effects. The north was war-weary after Cold Harbor, and the costly battles for Petersburg did not contribute to the support of Lincoln's policy. Only the capture of Atlanta had a decisive influence on the upcoming presidential elections. The President vigorously supported Grant in all of his endeavors. For a long time, the Confederation relied on McClellan's victory in the presidential election with the prospect of a negotiated peace. With Lincoln's victory that hope was gone and the South tried to postpone surrender as long as possible.

literature

- Earl J. Hess: In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications and Confederate Defeat. Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-8078-3282-0 .

- Ron Field: Petersburg 1864-1865. The longest siege (= Osprey Campaign Series). Osprey Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84603-355-1 .

- Robert Underwood Johnson, Clarence Clough Buell: Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. New York 1887.

- Bernd G. Längin : The American Civil War - A chronicle in pictures day by day. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1998, ISBN 3-86047-900-8 .

- James M. McPherson : Battle Cry of Freedom. Oxford University Press, New York 2003, ISBN 0-19-516895-X .

- James M. McPherson (Ed.): The Atlas of the Civil War. Philadelphia 2005, ISBN 0-7624-2356-0 .

- Noah A. Trudeau: The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864-April 1865. Louisiana State University Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0-8071-1861-0 .

- United States War Department: The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Govt. Print. Off., Washington 1880-1901.

Individual evidence

- ↑ average strengths during the campaign. Retrieved September 19, 2010 .

- ↑ losses. Encyclopedia Verginia, accessed September 19, 2010 .

- ↑ Military historians classify the period of the campaign differently. This article follows the classification of the NPS. National Park Service, accessed September 19, 2010 .

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, pp. 721f

- ↑ Personal Memoirs of US Grant, chap. 56, footnote 1. Bartleby.com, Inc., 2000, accessed September 19, 2010 (plan of operations).

- ↑ Personal Memoirs of US Grant, Appendix, para. 32. Bartleby.com, Inc., 2000, accessed 19 September 2010 (Grants report on Butler).

- ↑ Description of the battle. Encyclopedia Virginia, accessed September 19, 2010 (Old Men and Young Boys Battle).

- ^ Union losses. civilwarhome.com, October 16, 2001, accessed September 19, 2010 (Fox's Regimental Losses).

- ↑ The daily strength reports of the Northern Virginia Army were only fragmentary at this phase of the war, so the Confederate figures are only estimates

- ↑ Further orders. Retrieved October 15, 2010 (Official Records).

- ↑ supportive use of infantry. Retrieved October 15, 2010 (Official Records).

- ↑ Personal Memoirs of US Grant, chap. 57, para. 15. Bartleby.com, Inc., 2000, accessed February 26, 2011 (Grant's report on Burnside's proposal).

- ↑ Personal Memoirs of US Grant, chap. 57, para. 17. Bartleby.com, Inc., 2000, accessed February 26, 2011 (Grant's report on Burnside's proposal).

- ^ Mission Deep Bottom. Retrieved October 20, 2010 (Official Records).

- ↑ Shelby Foote : The Civil War, A Narrative: 3. Red River to Appomattox, p. 317. “I do not know that the necessity for his presence today is greater than it was yesterday.”

- ^ Union losses. civilwarhome.com, October 16, 2001, accessed November 5, 2010 (Fox's Regimental Losses).

- ↑ Battles & Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. 4, p. 548. The Ohio State University, 1956, accessed February 15, 2011 (The Century Magazine, 1884-1887, by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel).

- ↑ Summarized description in: James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, pp. 758ff

- ^ Union losses. civilwarhome.com, October 16, 2001, accessed November 13, 2010 (Fox's Regimental Losses).

- ^ Losses of the colored regiments. civilwarhome.com, October 16, 2001, accessed November 15, 2010 (Fox's Regimental Losses).

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 760

- ↑ Further orders. Retrieved November 13, 2010 (Official Records).

- ^ Union losses. civilwarhome.com, October 16, 2001, accessed November 23, 2010 (Fox's Regimental Losses).

- ↑ Personal Memoirs of US Grant, chap. 57 para. 28. Bartleby.com, Inc., 2000, accessed December 5, 2010 (English, on behalf of Sheridan).

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 777

- ↑ losses. Encyclopedia Virginia, April 29, 2009; Retrieved December 11, 2010 .

- ^ RE Lee: A Biography by Douglas Southall Freeman. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1934, accessed December 11, 2010 (consequences).

- ↑ losses. Encyclopedia Virginia, April 29, 2009; Retrieved December 11, 2010 .

- ^ Union losses. Cornell University Library, 2010, accessed December 14, 2010 (Official Records, Vol. 42, Part 1, p. 137).

- ^ Union losses. Cornell University Library, 2010, accessed December 14, 2010 (Official Records, Vol. 42, Part 1, p. 143).

- ^ Union losses. Cornell University Library, 2010, accessed December 16, 2010 (Official Records, Vol. 42, Part 1, p. 146).

- ^ Union losses. Cornell University Library, 2010, accessed December 16, 2010 (Official Records, Vol. 42, Part 1, p. 148).

- ^ Union losses. Cornell University Library, 2010, accessed December 16, 2010 (Official Records, Vol. 42, Part 1, p. 152).

- ^ Union losses. Cornell University Library, 2010, accessed December 15, 2010 (Official Records, Vol. 42, Part 1, p. 160).

- ↑ James M. McPherson: The Atlas of the Civil War. P. 185.

- ↑ James McPherson: Battle Cry of Freedom. P. 780.

- ^ Shelby Foote : The Civil War, A Narrative: 3. Red River to Appomattox, p. 785.

- ^ Union losses. Cornell University Library, 2010, accessed on December 21, 2010 (English, Official Records, Vol. 46, Part 1, pp. 63ff).

- ↑ Confederate losses. Civil War Preservation Trust, 2009, accessed December 21, 2010 .

- ↑ James M. McPherson: Battle Cry of Freedom. P. 844f

- ^ Union losses. Cornell University Library, 2010, accessed December 25, 2010 (Official Records, Vol. 46, Part 1, pp. 70f).

- ↑ Confederate losses. (No longer available online.) Greg Goebel, October 1, 2009, archived from the original on November 20, 2005 ; Retrieved December 3, 2017 (The American Civil War). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

Web links

- Petersburg Campaign in Encyclopedia Virginia

- Animation of the Richmond-Petersburg campaign

- The Battle of Petersburg : Maps of the battles, history articles, photos and news on how to get the battlefields

- Petersburg Battlefields

Coordinates: 37 ° 13 ′ 43.3 " N , 77 ° 21 ′ 37.4" W.