The begging woman from Locarno

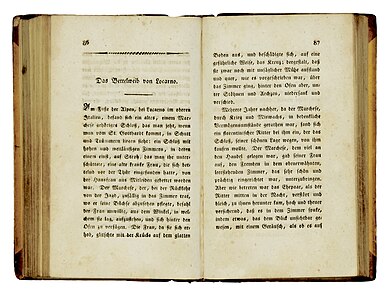

The begging woman from Locarno is a short story by Heinrich von Kleist . It was published for the first time in the tenth of Kleist's Berliner Abendblatt on October 11, 1810 under the abbreviation “mz”, and then in 1811 in the second volume of the stories (fig. Right).

content

The begging woman of Locarno appears on the surface of the text as a rather harmless ghost story according to the fashion of the time:

a begging woman is given shelter by a marquise in a room, but is ordered behind the stove by the marquis. On the way there, however, the beggar woman falls and injures herself so badly that she only makes the way behind the stove with a groan and dies there.

Years later, the now financially stricken Marchese wants to sell his castle to an interested knight. This stayed in said rooms, but has dismayed to know that there were noisily haunted . Something invisible rose in a corner and took heavy steps behind the stove to collapse there. The knight leaves immediately the next morning.

In order to dispel rumors that are hindering the sale of the castle, the Marchese now wants to investigate the matter himself; he too listens to the noises at midnight. Another night - now with the marquise and a servant - lets all three experience the ghost. The Marchese and the Marquise spend the next night in the room with a chain dog by their side.

When the dog backs away from the recurrence of the ghost, the marquise flees; The Marchese tries in vain to fight the invisible opponent with his sword, he lights the room: “The Marchese, overwhelmed by horror, had taken a candle, and the same one, paneled with wood everywhere as it was, on all four corners, tired of his life, infected. In vain did she send people in to save the unfortunate man; he had already perished in the most miserable way, and his white bones are still lying, gathered by the country folk, in the corner of the room from which he had asked the beggar woman of Locarno to rise. "(End)

shape

Years before the story Das Bettelweib von Locarno was written, Kleist made fun of the Würzburg library in a letter ; namely, there are exclusively “stories of knights, on the right the stories of knights with ghosts, on the left without ghosts” (to Wilhelmine von Zenge , 14 September 1800, underlining in the original).

In view of this testimony, it can be assumed that Kleist and the beggar woman, despite the publication in the broadly effective “Berliner Abendbl Blätter”, did not envisage a horror story exclusively intended for romantic entertainment .

Instead, Kleist lets the narrator get involved in numerous contradictions, which are, however, resolved - mostly involuntarily - by the readers; this is how the “fragility appears as a narrative principle” (Pastor; Leroy). Here are just a few examples:

- It actually only begs, but is accommodated by the marquise, although this is in the stately room of the castle (because the knight willing to buy is also accommodated there), but there the beggar woman then has to settle down on a heap of straw.

- The room is at least on the first floor, which also makes the behavior of the marquise towards an old, weak woman questionable.

- It is not clear why the Marchese even sent the beggar behind the stove; his indignation at the sight of the beggar woman could also have been directed against the marquise.

- The knight is accommodated in the "vacant room that was very nicely and magnificently furnished".

- The fall of the beggar woman, which actually led to his death, does not appear in the spooky noises.

- It is not clear why the Marchese and the Marquise want to check the spook another night.

- The concern of the marquise about the marquis at the end is inconsistent, nobody cares about a funeral of the deceased.

- How can the Marchese's bones end up in a ruined castle on an upper floor?

- ... etc.

Corresponding to the many absurdities of the text, there are numerous, sometimes diametrically contradicting, possible interpretations.

Interpretations

Typical for Kleist is the consistency with which the story ends: the death of the marches in overstimulation (madness) and fatigue is under certain circumstances apparently self-inflicted, but ultimately inevitable.

Socially critical readings

- The nobility is criticized for failing to meet their social responsibility. He is therefore haunted by the "ghosts" of his guilt. The beggar woman has slipped because the Marchese has put the law of the representation room over the necessary individual case - charity versus a needy. The haunted appearance only appears when the Marchese himself becomes needy and has to sell his castle.

- The aristocracy is criticized insofar as it does not fulfill its traditional duties:

The Marchese and the Marquise, whose too great distance from one another is already visible in the linguistically different names, which can also be shown with separate beds and rooms, take care of that themselves Extinction of their sex. The dog is an inadequate substitute for children: it is allowed into the room because the two of them want to have "something third, something alive" with them.

The first spook comes at the moment when the castle has to be sold because the financial circumstances have become imbalanced "through war and bad growth", that is, through the violation of economic due diligence.

Psychological readings

- The guilt ( primal scene ) sets in motion a devastating repetition compulsion.

- As the ghost emerges from its latency , it sets the instinct for self-destruction in motion.

- To the extent that the Marchese wants to control the ghost, it falls for him.

- As soon as the Marchese wants to get to the bottom of the spook last night with the shout "Who there?", The only direct speech in the story, and receives no answer, his fate seems to be sealed. In Shakespeare's tragedy Hamlet , which begins with these very words and in which a ghost and madness also play an important role, the question of identity falls back on the questioner: "No, answer: Stop, and say who you are."

- Just as the Marchese doesn't seem to remember the episode with the beggar woman, he too is forgotten in the end.

To the fantastic

The text does not clearly show that the apparition is causally related to the incident involving the beggar woman. During the haunted nights, "a noise" is reported that can be heard in the room. The ghost in the room is described as "incomprehensible" or "ghostly" (on this pastor; Leroy: nobody would say of thunder that it was thunderous).

The spook does not seem to be compatible with the laws of nature, since no causer can be identified, but the noise is still audible, i.e. subject to the laws of nature within limits. The fact that the ghost is a phantasm is ruled out by the various witnesses and the reaction of the dog, described in popular belief as being spiritually aware. The limbo between the natural and the supernatural corresponds to the essence of the fantastic and can be seen as a structural analogy to the limbo in the narrative discourse (contradiction between the narrator's voice and what is narrated).

Impact history

The begging woman from Locarno aroused different reactions:

- In Die Serapionsbrüder Lothar, ETA Hoffmann is enthusiastic about The Begging Woman of Locarno .

- As editor ( Heinrich von Kleist's selected writings ), Ludwig Tieck expresses himself at a loss: "The presentation is excellent, but in my view it is neither a ghost story, fairy tale nor novella."

- Theodor Fontane stated that the injustice committed was far too small for a moral narrative.

- Joseph von Eichendorff was more convinced in 1846: "Where in all of our poetic literature is there anything more desperate than the little, almost epigrammatic-gruesome story of the 'beggar woman from Locarno'?"

expenditure

- Berlin evening papers . Edited by Heinrich von Kleist. Reprographic reprint of the Berlin edition 1.X.1810 to 30.III.1811. Afterword and index of sources by Helmut Sembdner . Darmstadt 1982. This reprographic reprint is based on the following edition: Berliner Abendblätter (1.X.1810 to 30.III.1811). Heinrich von Kleist. With an afterword by Georg Minde-Pouet. Leipzig 1925 (= facsimile prints of literary rarities, 2).

- Heinrich von Kleist: "All stories" Ed. Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, Munich 1980 ISBN 3442075327

- Heinrich von Kleist: Complete Works. Brandenburg edition . Ed .: Roland Reuss ; Peter Staengle . Vol. 2/5: The begging woman from Locarno. The boulder . Saint Cecilia or the violence of music . Basel, Frankfurt am Main 1997.

- Heinrich von Kleist: The beggar woman from Locarno . In: All works and letters , 3: Stories, anecdotes, poems, writings. Ed .: Klaus Müller-Salget. Frankfurt / Main 1990 (= Bibliothek deutscher Klassiker , 51), pp. 261–264. ISBN 9783618609636

- Heinrich von Kleist: The beggar woman from Locarno . In: Complete Works and Letters . Ed .: Helmut Sembdner. Munich 2001 (= DTV , 967). ISBN 9783423129190

- Heinrich von Kleist: The engagement in St. Domingo / The begging woman from Locarno / The foundling. Stuttgart (= Reclam , 8003). ISBN 9783150080030

literature

- Bühlbacher, Hermann: Heinrich von Kleist: Of collapsing architecture and the "fragile furnishings of the world": ruins and spooks. The begging woman from Locarno. In: Ders .: Constructive Destruction. Depictions of ruins in the literature between 1774 and 1832. Bielefeld 1999, pp. 183–189.

- Greiner, Bernhard: Kleist's dramas and stories. Experiments on the "fall" of art. Tübingen, Basel 2000 (= UTB ), pp. 315–326. ISBN 3825221296

- Hilliard, Kevin: 'The story of knights with a ghost': The Narration of the Subconscious in Kleist's 'Das Bettelweib von Locarno'. In: German Life and Letters . N. S. 44/4 (1991), pp. 281-290.

- Jürgens, Dirk: "... and after summarizing a few things". Kleist's "Begging Woman from Locarno" . In: Contributions to Kleist research , 2001. ISBN 3-9807802-0-1

- Oberlin, Gerhard : The narrator as an amateur. Fictitious narration and surreality in Kleist's 'Bettelweib von Locarno' . In: Kleist yearbook . Stuttgart, Weimar 2006, pp. 100-119. ISBN 9783476021595

- Pastor, Eckart; Leroy, Robert: Fragility as a narrative principle in Kleist's 'Begging Woman from Locarno'. In: Etudes Germaniques , 34 (1979), pp. 164-175.

- Schmidt, Jochen: Heinrich von Kleist. The dramas and stories in their epoch . Darmstadt 2003. ISBN 9783534157129

- Staiger, Emil: Heinrich von Kleist. “The beggar woman from Locarno.” On the problem of dramatic style. In: Deutsche Vierteljahresschrift 20 (1942), p. 116ff. Also in: Heinrich von Kleist. Articles and essays. Ed .: Müller-Seidel, Walter. Darmstadt 1967 (= ways of research , 147), pp. 113–129.

- Criticism of Staiger's interpretation: Schmidt, Siegfried J .: Interpretationsanalysen . Munich 1976, pp. 93-104.

Web links

- The begging woman from Locarno as an online text in the Gutenberg-DE project

- The begging woman from Locarno as PDF (33 kB) from the Kleist Archive Sembdner

- The begging woman from Locarno as an audio recording with a CC license

Individual evidence

- ↑ Reinhold Steig: Heinrich von Kleist's Berlin fights . Berlin, Stuttgart 1901, pp. 521-530, cited above. according to www.textkritik.de

- ↑ Complete Works and Letters , 3 (Ed. Müller-Salget), p. 264.

- ^ Heinrich von Kleist: Complete Works. Brandenburg edition . Ed .: Roland Reuß, Peter Staengle. Vol. 4/1: Letters March 1, 1793 - April 1801. Basel, Frankfurt am Main 1996, p. 294.

- ↑ Largely based on: Pastor; Leroy.

- ↑ On this v. a. Bühlbacher.

- ↑ See Schmidt, Jochen.

- ↑ See Gerhard Oberlin .

- ^ Hamlet in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ↑ See Hilliard.

- ↑ See Greiner.

- ↑ Complete Works and Letters , 3 (Ed. Müller-Salget).