Byzantine literature

The term Byzantine literature refers to the Greek- language literature of the Eastern Roman / Byzantine Empire , which extends from late antiquity to 1453. The name is derived from the old Doric colony Byzantion on the Bosporus , which the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great made the second capital of the Roman Empire in 330 and which quickly developed into the spiritual metropolis of the empire. As Latin lost its dominant position as an imperial language, Greek, which was spoken as the mother tongue of almost a third of the inhabitants of the Eastern Empire, developed into the preferred language of all educated people and in 629 also became the official state language. Of course, many loanwords have been taken from Latin .

Historical and cultural background

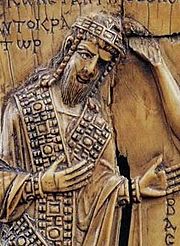

After the fall of the western part of the empire, Byzantium became the heir to the Roman imperial culture, which had been characterized by an unprecedented mixture of philosophical directions and religious cults since the Roman Empire. With the rapid growth of an inwardly united Christianity (after the First Council of Nicaea in 325), the necessity arose to integrate it into the structure and world of thought of the empire and to elevate it to the state religion. Christian doctrine and thus patristic literature were also integrated into the Roman world of thought and achieved a monopoly position, while the (Eastern) Roman emperors acted theocratically as earthly representatives of God and determined the direction in all areas of art and literature. Byzantium quickly attracted all creative powers through this synthesis of political and spiritual power. Other intellectual centers such as Alexandreia and Antiocheia , and later also Athens , quickly lost their importance, not to mention the intellectual life in the provinces.

The Byzantine language form of Greek since around 600 is also called Middle Greek . Its characteristic is the changed metric . While the spoken vernacular developed continuously from the 11th or 12th century to today's modern Greek, the learned scriptures continued to be written in a wide range of often incomprehensible artificial language. This linguistic dualism shaped the entire Byzantine period, even if learned authors increasingly made concessions in the form of the use of vernacular elements.

Genres

Byzantine literature can be divided into three main genres:

- the high-level historiography in Attic Greek (based on the classical Attic );

- the scientific literature, especially theological-dogmatic, later increasingly popular theological writings;

- Poetry, partly inspired by classical narratives and genres, partly as a folk tale and written in more recent forms; Religious poetry, too, stuck to the Attic narrative form and the classical genre, whereby the metrics of the old forms were mostly no longer represented by the contrast of long and short syllables, which were no longer linguistically differentiated, but rather by word accents.

Liturgical poems have been sung since the 7th century; the melodies were fixed in a kind of musical notation since the end of the 10th century.

Historiography: historiography and chronicle literature

- The history is considered significant accomplishments of the Byzantine literature (see Byzantine history ). Most of the historians were high officials or officers. You wrote for an educated audience; her style is upscale and elegant, but artificial. In their work they imitated the Classical Greek (Attic) grammar and literature as much as possible; therefore their language deviates strongly from the way of speaking of their time (but different from the numerous chronicles that were not written in the standard language). Important historians were:

- Prokopios (6th century; followed by Agathias , Menander Protektor and Theophylaktos Simokates ),

- Emperor Konstantin Porphyrogénnetos with the work De Administrando Imperio , Greek: Προς τον ίδιον υιόν Ρωμανόν , which also contains information about the neighboring peoples,

- Leon Diakonos (10th century),

- Michael Psellos (philosopher and polymath of the 11th century, representative of a Byzantine "humanistic renaissance" of antiquity),

- Anna Komnena (12th century), Johannes Kinnamos and Michael and Niketas Choniates (12th and 13th centuries)

- Georgios Gemistos Plethon († 1453, Neoplatonic critic of Christianity)

- Georgios Phrantzes and Laonikos Chalkokondyles , who described the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

- The Hagiography : Biographies of Christian Saints and Popular Genres of the Byzantine Period

- Later the chronicle literature made more use of the oral Greek language.

- Chroniclers - including numerous monks - were Johannes Malalas (6th century), Theophanes (8th century), Georgios Monachos (9th century), Johannes Skylitzes (11th century), Johannes Zonaras and Kedrenos (around 1200).

- Significant chronicles of Machaeras and Boustrónios, which describe the history of Cyprus under the House of Lusignan, as well as the Chronicle of Morea , which describes the Principality of Achaia , are added from the area around the Byzantine Empire .

The poetry

- Individual authors in the Anthologia Palatina :

- The epic :

- Digenis Akritas and the Acritic Songs

- Melische Poetry (liturgical hymns)

- Romanos Melodos , Andrew of Crete , John of Damascus, Cosmas of Jerusalem

- Panegyric poetry

Theology

After the fall of Constantinople

After the fall of Constantinople, fewer and fewer works were written in Attic Greek, while folk literature was written in spoken language. In general, the 15th / 16th Century regarded as a transition period between Byzantine and modern Greek literature . At the princely courts of the Danube principalities (in today's Romania ), however, the Byzantine heritage was maintained until the era of the European Enlightenment. In Western Europe, after the fall of Constantinople to Italy and France, Greek scholars such as Demetrios Chalkokondyles and Janos Laskaris were involved in the preservation and renaissance of Greek literature.

literature

- Franz Dölger : The Byzantine Literature. In: Walter Jens (Ed.): Kindlers new literature lexicon. Volume 19, Munich 1996, pp. 961-965.

- Roderick Beaton : From Byzantium to Modern Greece: Medieval Literature and its Modern Reception (Farnham: Ashgate 2008), ISBN 978-0-7546-5969-3 .

- Hans-Georg Beck : History of Byzantine Folk Literature (Byzantine Manual II.3 [HdAW XII.2.3]), Munich 1971.

- Hans-Georg Beck: Church and theological literature in the Byzantine Empire . Munich 1959.

- Herbert Hunger : The high-level profane literature of the Byzantines , 2 volumes, 1978.

- Jan Olof Rosenqvist: The Byzantine Literature. From the 6th century until the fall of Constantinople in 1453 . de Gruyter, Berlin, New York, 2007, ISBN 3110188783 .

See also

Web links

- Byzantine literature . In Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon, Volume 3. Leipzig 1905, pp. 673-674.

Individual evidence

- ^ Franz Dölger: The Byzantine Literature. In: Walter Jens (Ed.): Kindlers new literature lexicon. Volume 19, Munich 1996, p. 961 f.