Modern Greek literature

The modern Greek literature is the literature based on the Byzantine - Greek vernacular or on the modern modern Greek , which developed in the regions of the Ottoman Empire settled by Greeks after the fall of Constantinople . Since independence in 1829 it has been the national literature of Greece and the literature of the Greeks living in the diaspora .

From the fall of Constantinople to Greek independence

After the fall of Constantinople, fewer and fewer works were written in Attic Greek , while folk literature had been written in spoken language since at least the 11th century. In general, the 15th / 16th Century viewed as a transition period between Byzantine (Middle Greek) and Modern Greek literature. This process went faster in the islands ruled by Venice than on the Turkish-ruled mainland, which was more under the influence of Orthodoxy. The first work in Modern Greek was printed in Venice in 1509.

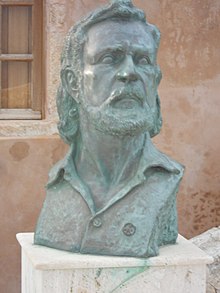

In the Venetian-ruled Crete , the rhyming love poem Erotokritos (around 1610) by Vitsentzos Kornaros , written in the local dialect and comprising 10,000 Byzantine 15-silver, stands out. The theater also developed here ( Erofili by Georgios Chortatzis around 1600). The prose, on the other hand, was more a matter of the Turkish-ruled mainland; Late Byzantine forms such as the world chronicle lived on here, with a gradual transition to the vernacular, which was also introduced as a scientific language by Greek scholars in the Danube principalities (at the royal courts in Bucharest and Iași , the “cradle of Romanian culture”) in the 18th century . The Roman Catholic Church and the Western European Reformation left further traces in the form of Orthodox humanism. With Rigas Velestinlis (executed in 1798), under the influence of the French Revolution, a patriotic poetry began at the end of the 18th century that shaped the entire 19th century.

The 19th Century: Wrong Paths in Artificial Language

After the liberation of Greece from Turkish rule, the Greek language dualism became more noticeable, which already went back to the time of Alexander the Great (loss of vowel length, grammatical and syntactic simplification). Adamantios Korais created an upscale Greek ( Katharevousa ) that was cleared of vulgarisms and Turkish foreign words , but which differed from the learned Attic Greek. In between there were a number of gradations.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the orally transmitted folk songs were first known abroad, which were enthusiastically collected in Germany by Werner von Haxthausen and Wilhelm Müller . Goethe also tried to translate it. However, most Greek authors wrote in the artificial language after the liberation, which led to lengthy rhetorical texts. Works by poets such as Dionysios Solomos from the Ionian Islands, who discovered the works of German Romanticism for his country and who wrote the text of the Greek national anthem . The writings of the liberal-enlightened scholars in the Danube principalities, who wrote in the lively vernacular ( Dimotiki ), were disregarded by the conservative-elitist poets of patriotic odes such as Andreas Kalvos , because they regarded the Dimotiki as a slave language. Another important proponent of high-level language was Alexandros Rizos Rangavis (Rhankaves). Of course, this educational program turned out to be a dead end. The works of the historian Konstantinos Paparrigopoulos , who tried to tie in with ancient history as well as to preserve the legacy of Orthodox Byzantium, which is more firmly anchored in the consciousness of the population, contributed more to the formation of national identity . The politician Spyridon Trikoupis wrote the standard work on the history of the Greek revolution in the 1850s .

1888 to 1930: The triumph of the vernacular

Since around 1880, with romanticism and the re-evaluation of folk songs, which were first collected in Western Europe, the vernacular was rediscovered. The book To taxidi mu (“My Journey”, 1888) by Odessa- born Ioannis Psycharis was groundbreaking for the generation of the 1880s ; it led, as it were, to a language revolution. The Dimotiki, however, prevailed more quickly in poetry than in prose. The extensive and expressive lyrical work of the influential Kostis Palamas , who introduced a new kind of metric , and the lyrics of Angelos Sikelianos , who also tried to revive the ancient dramaturgy, stand for this .

In the following all literary directions developed that were also represented in the rest of Europe: realism, naturalism, later symbolism, Parnassia , socialist workers' novel, surrealism, existentialist prose. The focus of the epic was initially on genre narratives from the life of the rural population. They have strong regionalist traits. Alexandros Papadiamantis from Skiathos wrote three novels and 170 stories (including the best-known: "The Murderess"), most of which are set in his home country, in a moderately antiquated Katharevousa with high literary standards, which he was not always able to realize successfully . His cousin Alexandros Moraitidis , who dealt with similar topics, also comes from Skiathos . Georgios Vizyinos (Bizyinos) from Eastern Thrace created the first character representations in addition to poetry. Andreas Karkavitsas from the Peloponnese connects in his descriptions of the seafaring life to both the naturalism Èmile Zola and the fantastic romanticism of ETA Hoffmann or Gogol .

After the lost war in 1897, Palamas and other authors saw their task in restoring the lost self-confidence to the Greek nation. This strengthened the position of the "dimotizists". Konstantinos Chatzopulos from Aetolia , who lived in Germany for a long time, was a novelist and poet with a symbolist attitude. He showed that classical texts like Goethe's Iphigenie and Faust can be translated into the Dimotiki, but he was also interested in German socialism and founded the type of socially critical narrative that also made Konstantinos Theotokis stand out. Was committed to the symbolism also of Arcadia coming poet Kostas Karyotakis . In the äygptischen Diaspora created Constantine Cavafy 's influenced by the ancient lyrical works.

The Cretan Nikos Kazantzakis was the most important representative of a generation of expressive and successful storytellers and novelists born after 1880. The pathos of his novels ( Alexis Sorbas , 1946) was enthusiastically received abroad.

Generation from 1930: connection to the modern age

The generation of the 30s ( γενιά του '30 ), i.e. the authors who first published between 1930 and 1940, were shaped by the defeat in the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1923. They created the linguistic forms of modern Greek literature and distanced themselves further from the Katharevousa; some of its representatives are influenced by surrealism (such as Andreas Embirikos and Nikos Engonopoulos ) or by neorealism . Characteristic of the phase are a simpler language, a simplification and clearing of the extensive vocabulary of Palamas.

In prose, anti-war literature in the 1920s and urban narrative in the 1930s replaced the portrayal of life in the countryside in a picturesque manner. Elias Venesis , who was born on the Turkish Aegean coast, and Giorgos Theotokas , who was born in Constantinople, treat the suffering of the refugees of the 1920s and 1930s in their realistic anti-war and socially critical prose. Stratis Myrivilis , who was born in Lesbos , which was still Ottoman at the time , and who had already emerged as an author in 1914, became the most important narrator of the 1930 generation (“Life in the Grave” 1924, German 1986). Angelos Terzakis (1907–1960) and Mitsos Karagatsis (1908–1960; actually Dimitris Rodopoulos) wrote short stories, intelligently composed novels and psychological dramas . Kosmas Politis (1888–1974) describes the passions of young people from a psychoanalytic perspective. Giorgos Theotokas also devotes himself to the problems of youth in his novel Argo . The left-wing authors are Kostas Varnalis, born in Eastern Rumelia , and Petros Pikros .

The great poets of this generation include the Nobel Prize winners Giorgos Seferis (1963) and Odysseas Elytis (1979) as well as the poet, playwright and translator Nikos Gatsos , from whose bourgeois elitism the poet Giannis Ritsos distinguished himself . Born in the Chinese diaspora, the sailor Nikos Kavvadias did not see himself as a poet, but became popular through his poems.

This literary development, through which Greece had caught up with international literature, was brutally interrupted by the German occupation from 1941 to 1944 and the civil war that followed. For the poet and playwright Iannis Skarimbas , the invading “Prussians” were “robots [...] with copper hearts”. Authors of the resistance and representatives of socialist realism such as the popular Menelaos Loundemis (Loudemis), who describes the invasion of the "devil's army" from the perspective of gypsies, or Dimitris Chatzis often had to spend long periods of time in exile. From a bourgeois-conservative point of view, the events of Lukis Akritas or Iannis Beratis were presented.

After 1949: literary reappraisal of the wars, new political turmoil and dictatorship

The experiences of the world war, the resistance and the civil war, which was waged with great cruelty, contributed to the polarization of social and literary life into a right and a left camp. Much of the literature remained devoted to these subjects, including the work of Rodis Kanakaris-Roufos . Stratis Tsirkas published 1961-65 the trilogy "Taxless Cities" ( Ακυβέρνητες πολιτείες ) about the Greek exile forces in Egypt and Palestine, which revolted in 1944 against the Greek (royalist) and English military leadership. As a loner, Kazantzakis wrote his most important novels after 1945.

Regionally, literary production was increasingly concentrated on Athens and Thessaloniki . In Athens in the 1950s and 1960s, the novelist and theater manager Tasos Athanasiadis worked at the National Theater . Also active there was Pavlos Matesis . It was not until she was around 50 that Dido Sotiriou , who came from Smyrna and was politically left-wing, published her first novel. On the periphery, in Crete, was the journalist Lily Zografou , who dealt with the patriarchal structures of her homeland. Some of her 24 novels became bestsellers and came to Germany with a long delay.

The post-Surrealist movement, “fantastic realism”, played a larger role, with representatives such as Lefteris Poulios .

During the military dictatorship , many authors and artists again went into exile, including Vasilis Vasilikos , who grew up in Thessaloniki and the author of the novel Z , which Constantin Costa-Gavras filmed in 1969 . The funeral of Seferis in September 1971 turned into a great rally against the colonels.

After the end of the dictatorship in 1974

After the end of the military dictatorship, not only it, but also the war and civil war, was dealt with again. Aris Alexandrou was one of those exiled after 1944 and who lived in exile for years after 1967 . His only novel Die Kiste (1974, German: Munich 2001) is a Kafkaesque parable about a death squad in the civil war. The work of Menis Koumandareas remained committed to socialist realism .

Since the 1980s, more and more women have spoken up, such as the anarchist poet and actress Katerina Gogou and Ioanna Karystiani , who also became known in Germany through the tragic romance novel “The Women of Andros” ; also Evgenia Fakinou , who also wrote numerous children's books, Maro Duka and Margarita Karapanou and the poet Kiki Dimoula .

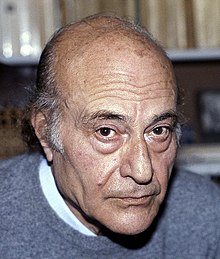

The Greek-Armenian Petros Markaris became known as the scriptwriter of the director Theo Angelopoulos , who also writes plays and successful socially critical detective novels and emerged as a Brecht and Goethe translator. For this he received the Goethe Medal . Jorgos Maniotis developed from a playwright (" common sense ") to a prose writer.

Since 2000: New social issues and crises

After 2000, a new generation of lyric poets and playwrights appeared, including the poet Dimitris P. Kraniotis and the postmodern writer Dimitris Lyacos . His Poena Damni trilogy trilogy ( Z213: Exit , Mit den Menschen von der Brücke , The First Death ), a cross-genre work that has been revised over a period of 30 years, is arguably the most reviewed work in Greek literature and one of the most prominent works of postmodern literature published in the new millennium. Attempts to literate colloquial language and sociolects dominate the prose . Thematically, social problems and urban neuroses , depictions of violence, gender conflicts, fringe groups and subcultures take up an ever larger space.

Bar Flaubert (2000) by Alexis Stamatis , a novel about a young writer's self-discovery, became an international bestseller . Novels by Christos Chryssopoulos have been translated into many other languages , including Parthenon (2018), a parable on the overwhelming cultural heritage destroyed by a terrorist bomb.

Since the financial crisis, the Greek book market has been in an existential crisis and has shrunk by around 50 percent. Numerous publishers and bookstores therefore had to close. In particular, the market for high-quality literature shrank. Many Greek authors now live abroad, such as Panos Karnezis and (at times) the cosmopolitan Soti Triantafillou . The crisis has also become the subject of current literature ( Faule Kredite, crime novel by Petros Makaris, German 2012).

Book fairs and literary prizes

Since 2003 there has been an international book fair in Thessaloniki every May, each with a guest country and a main topic, as well as a children's book fair. For example, the 400th anniversary of El Greco's death was the topic in 2014 . The 2012 literary prize of the European Union went to the young authors Kostas Hatziantoniou (* 1965) for Agrigento , in 2014 Makis Tsitas (* 1971) for God is my witness and in 2017 Kallia Papadaki (* 1978), who also writes scripts, for Dendrites . State literary prizes are awarded annually in different categories.

literature

- Λεξικό Νεοελληνικής Λογοτεχνίας. Πρόσωπα, έργα, ρεύματα, όροι . Αθήνα: εκδ. Πατάκη 2007, ISBN 978-9-60162-237-8 .

- Roderick Beaton : An Introduction to Modern Greek Literature , second revised. (Oxford University Press 1999; 1st edition Oxford: Clarendon Press 1994; Greek translation 1996), Google Books: [2] .

- Roderick Beaton, David Ricks (eds.): The Making of Modern Greece: Romanticism, Nationalism, and the Uses of the Past (1797-1896) (Farnham: Ashgate 2009), ISBN 978-0-7546-6498-7 , Google Books: [3] .

- Κ. Θ. Δημαράς : Ιστορία της νεοελληνικής λογοτεχνίας . Athens: Ικαρος 1975, English: A History of Modern Greek Literature , Albany (New York): State University of New York Press 1972, Google Books: [4] .

- Dimosthenis Kourtovik: Contemporary Greek Writers. A critical guide . Romiosini , Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-929889-35-8 .

- Peter Mackridge et al. (Ed.): Contemporary Greek Fiction in a United Europe. From local history to the global individual . Legenda Books, Oxford 2004, ISBN 1-900755-85-8 .

- Bruce Merry : Encyclopedia of modern Greek literature. Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport CT, 2004, ISBN 0313308136 , Google Books: [5] .

- Ulrich Moennig : The modern Greek literature . In: Walter Jens (Hrsg.): Kindlers new literature dictionary (1 CD-ROM). Systema-Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-634-99900-4 (here: Vol. 19, pp. 972-979).

- Modern Greek literature. In: Der Literatur Brockhaus, Vol. 2: FU-OF. Mannheim 1988, pp. 692-694.

- Johannes Niehoff-Panagiotidis : Modern Greek literature . In: Hubert Cancik et al. (Ed.): The New Pauly. Encyclopedia of Antiquity (DNP). Metzler, Stuttgart 1996-2003, ISBN 3-476-01470-3 (here: Vol. 15/1, pp. 895-918).

- Linos Politis : History of Modern Greek Literature . Romiosini, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-923728-08-5 .

- Pavlos Tzermias : The Modern Greek Literature. An orientation. Francke, Tübingen 1987; 2nd edition: Modern Greek literature. Homer's legacy as a burden and an opportunity. Francke, Tübingen 2001, ISBN 3-7720-1736-3 .

- anthology

- Isidora Rosenthal-Kamarinea : The sin of my mother. dtv, Munich 1985.

See also

- List of modern Greek writers

- List of well-known modern Greek translators

- List of well-known neo-Greekists

Individual evidence

- ↑ Moenning 2002, p. 972 f.

- ↑ Athanasios Anastasiadis: The North in the South: Kostantinos Chatzopoulos (1868-1920) as a translator of German literature. Peter Lang Verlag 2008, p. 110 ff.

- ↑ Isidora Rosenthal-Kamarinea (Ed.): Epilogue to: The sin of my mother. Stories from Greece. dtv, Munich 1985, p. 247 ff.

- ↑ Isidora Rosenthal-Kamarinea 1985, p. 250 ff.

- ↑ https://bombmagazine.org/articles/dimitris-lyacos/

- ↑ http://gulfcoastmag.org/journal/30.1-winter/spring-2018/an-interview-with-dimitris-lyacos/

- ↑ Dimitris Lyacos , in: Fran Mason: Historical Dictionary of postmodern Literature and Theater , 2nd edition, Rowman and Littlefield 2016, pp. 276–77.

- ↑ Philip Shaw: The Sublime. Chapter: The Sublime is Now, p. 176. Routledge 2017. [1]

- ↑ This is how hard the crisis hits Greece's authors. Interview with Konstantinos Kosmas, Deutschlandfunk Kultur, January 21, 2015.

- ↑ Marianthi Milona: Greek bookstores in crisis. , Deutschlandfunk, May 20, 2013.