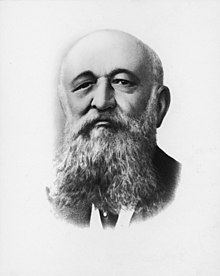

Davide Giordano

Davide Giordano (born March 22, 1864 in Courmayeur , † February 1, 1954 in Venice ) was an Italian surgeon and medical historian , institute director and politician. He was mayor of Venice from 1920 to 1923, commissario straordinario until 1924. He supported the fascists who appointed him the first mayor. Giordano was a senator and proponent of euthanasia from 1924 to 1945 .

Life

Davide Giordano was born in 1864 in the Aosta Valley to Giacomo and Susetta Hugon, who were both Waldenses from Torre Pellice . He attended primary school in Prarostino and secondary school in Pinerolo . In 1881 he enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine and Surgery at the University of Turin . In the surgical department of the Hospital Ospedale Maggiore S. Giovanni Battista , the director Giacomo Filippo Novaro accepted him as a replacement for his sick assistant, and he was assessore all'igiene from 1884 to 1887. During this time he made his first medical publications, which later Medical history followed.

On July 6, 1887, he completed his Rigorosum , his doctoral thesis dealt with the etiology of osteomyelitis . Immediately afterwards he was hired as a surgeon at the Waldensian hospital in Torre Pellice. Its catchment area thus included the municipalities of Bobbio , Villar Pellice , Luserna-San Giovanni , Angrogna and Rorà . But in 1891 Novaro called him to the University of Bologna as assistant and head of the laboratory there. He also taught surgery techniques. In 1894 he applied to Venice , where on July 16 he took over the management of the second surgical department at the Ospedale civile . He operated practically the entire range of possible cases, without any specialization. The house was recognized as a university hospital.

Giordano wrote more than 200 medical articles, as well as manuals and also on the surgery of the war, he wrote some essays. In 1915 he supported euthanasia.

In addition to surgery, Giordano dealt with the history of medicine . In 1907 he became a founding member of the Società italiana di storia critica delle scienze mediche e naturali , whose president he became, as well as from 1930 to 1938 president of the Società internazionale di storia della medicina .

He wrote about the Bolognese Leonardo Fioravanti (1518–1588), Bologna 1920 and about Giambattista Morgagni (1682–1771), Turin 1941. In 1930 his students collected the medical-historical essays in: Scritti e discorsi pertinenti alla storia della medicina e argomenti diversi , which appeared in Milan.

In 1919 or 1920, together with Pietro Orsi and Giovanni Battista Giuriati, he founded the group Alleanza nazionale (not to be confused with the Alleanza Nazionale founded in 1995 ), of which he was president. On a list he ran in Venice, together with nationalists, liberals and Catholics, against the socialists for mayor's office. He was supported by the Catholic Partito Popolare Italiano , although he was not a Catholic. Their leader Luigi Sturzo visited Venice on March 18, 1919. In the spring of 1919 the fascists founded a so-called fascio di combattimento , the second foundation of its kind after that of Mussolini in Milan on March 23 of the same year. In the November 1919 elections, the PPI won 3,156 votes, the Liberals 3,200 and the Democrats 3,329. The Socialists received 9,883 votes. In the provinces, however, the PPI received 16,699 votes, the socialists 25,323.

Giordano emerged victorious from the election and remained in office from 1920 to 1923. Initially, Giordano continued the cultural policy of his predecessors. In 1921 the Sale delle Procuratie Nuove and the Ala Napoleonica on St. Mark's Square became the seat of the Museo Correr .

Under Gino Covre , a war returne from Friuli, in November 1921 his Cavalieri della Morte attacked the office of the Communist Party, which had split off from the Socialists in January. Eight months later, the right-wing group that killed eight people was suppressed by the fascists. At that time the socialists continued to defend their areas around Via Garibaldi, around Campo Santa Margerita and in Cannaregio .

On September 28, 1921, the Venetian fascists protested against their party's agreement with the Socialists and the Confederazione Generale del Lavoro (CGL). The leader of the fascists in Venice was the lawyer Pietro Marsich , to whom it can be attributed that the Venetian fascists went different ways than in the rest of the country. Marsich came into opposition to Mussolini. In June 1922 Marsich had to give up his newspaper Italia Nuova . He had left the party three months earlier. He died in 1928.

The fascists, also gentlemen of Venice since the March on Rome in October 1922, stormed the Casa del Popolo in Mestre . They ousted radicals within the party, such as Girolamo di Causi, whom the Cavalieri della Morte had beaten near San Cassan in September 1921. Anita Mezzalira , who organized the women in the tobacco factory, was arrested and released, she was banned from all political activity and she was under surveillance until 1945. At the end of 1925, the so-called " Roman greeting " became mandatory.

In June 1923 Mussolini visited Venice, Giordano accompanied him on a gondola ride. The fascists pursued plans for a Greater Venice and in 1923 began corresponding incorporations, for example of Pellestrina . Murano and Burano followed in 1924 , then the mainland cities.

In 1924 Giordano was appointed commissario straordinario . For his services as a medical advisor to the fascist militia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale , he was appointed senator in 1924. In 1927 he took over the provisional management of the Scuola superiore di economia at Ca 'Foscari, the Venetian university . Its previous head, the economic historian Gino Luzzatto , had been ousted from office and his colleagues were threatened with violence.

Giordano was a founding member of the International Society for Surgery in Brussels in 1903. In 1926 he was President of the International Surgery Congress in Rome, where he gave a lecture in Latin. He was also president of the Ateneo Veneto from 1930 to 1931. In this function he was personally asked by the Podestà Giovanni Marcello at the time to organize an exhibition on the "Venetianità" of the island of Corfu claimed by the fascist regime . In 1931 Giordano became president of the university board of directors.

He left in 1934 for reasons of age. In 1936 Giordano was elected a member of the Leopoldina .

After the end of the war, on July 31, 1945, he was stripped of the rank of senator. In 1946, despite his involvement in the crimes of the fascist regime, he became vice-president of the Società italiana di chirurgia .

His overall history of surgery, which he began in the last years of his life, remained unfinished. He died in Venice on February 1, 1954.

The Italian Communist Party bought his house near San Marcuola and set up its party office there.

Works

- Dell'innesto degli ureteri nel crasso intestino e della asportazione della vescica e della prostata , in: La Riforma medica, VIII (1892), pp. 495-498

- Sulla questione se si possano trapiantare gli ureteri nel retto , in: La Clinica chirurgica, II (1894), pp. 80-91.

- Sulla asportazione completa per il ventre dei genitali interni invece della salpingectomia bilaterale , in: Rivista veneta di scienze mediche, XXIII (1895), pp. 245-265.

- Osservazioni di nefrectomia e nefropessia simultanea, perché il rene sano era mobile , in: Memorie chirurgiche pubblicate in onore di E. Bottini , Palermo 1903, pp. 248-264.

- Intervento chirurgico in nefriti , in: Rivista veneta discienze mediche, XLIV (1906), pp. 433-447.

- The treatment of renal hematuria , in: Klinisch-therapeutische Wochenschrift, XVI (1909), pp. 1157-1162.

- Traitementdes hématuries rénales , in: Congrès international de médecine, 1909, Budapest 1910, pp. 213-231.

- Les résections larges de la vessie , in: Annales des maladiesdes organes génito-urinaires, II (1911), pp. 2231–2247.

- Surgical renal. Osservazioni e riflessioni , Turin 1898.

- Nuove conoscenze intorno alla patologia e terapia del rene malato dal punto di vista chirurgico , Piacenza 1909.

- Contributo alla conoscenza ed alla cura dell'ascesso epatico , in: Annali di medicina navale, V (1899), pp. 33-54.

- Contributo alla conoscenza degli ascessi retroepiploici da pancreatite suppurata , in: La Clinica chirurgica, VIII (1900), pp. 242-251.

- Documents pour l'histoire des pancréatites suppurées , in: Archives des maladies de l'appareil digestif et des maladies de la nutrition, II (1908), pp. 23-31.

- La chirurgia delle ascite per cirrosi epatica , in: Rivista veneta di scienze mediche, XLVIII (1908) pp. 289-306.

- L'ascesso del fegato , in: La Riforma medica, XVIII (1912), pp. 561-565.

- L'abcès du foie , in: Archives des maladies de l'appareil digestif et des maladies de la nutrition, VI (1912), pp. 492-501.

- La chirurgia del ceco , in: Archivio ed atti della Società italiana di chirurgia, XXVII (1921), pp. 249-281.

- Contributo alla cura delle lesioni traumatiche ed alla trapanazione del cranio , in: L'Osservatore, XLI [1890], pp. 5-15.

- Contributo allo studio delle lesioni chirurgiche del pneumogastrico , in: La Clinica chirurgica, I [1893], pp. 241-272.

- Sulle lesioni del pneumogastrico considerate dal punto di vista chirurgico: osservazioni , in Archivio per le scienze mediche, XVII [1893], pp. 367-380.

literature

- Stefano Arieti: GIORDANO, Davide , in: Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani , 55 (2001)

Web links

- GIORDANO Davide , Senato della Repubblica website

Remarks

- ↑ Davide Giordano: I microbi piogeni nella eziologia della osteomielite infettiva acuta , Turin 1888th

- ^ Davide Giordano: Manuale di medicina operativa , Turin 1894; ders .: Compendio di chirurgia operatoria italiana , Turin 1911.

- ↑ Davide Giordano: Impressioni di chirurgia bellica , in: Attualità medica, IV (1915), pp. 572-588 and ders .: Ove la cosidetta "chirurgia di guerra" nella chirurgia quotidiana si confonde , in: La Riforma medica, XXXIV ( 1918), pp. 162–165 or Chirurgia in tempo di guerra: conferenze ad ufficialimedici , Turin 1917.

- ↑ Rassegna storica del risorgimento 30 (1943)

- ↑ Edoardo Savino: La nazione operant. Albo d'oro del fascismo, profili e figure , Istituto geografico De Agostini 1937, p. 325.

- ^ Richard JB Bosworth: Italian Venice. A History , Yale University Press, 2014, p. 115.

- ↑ Ateneo veneto 38 (2000) 276.

- ↑ Lavinia Riva Sarcinelli: Requiem Per Venezia , 1970, p. 87.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Giordano, Davide |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian surgeon, Mayor of Venice (1920–1923) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 22, 1864 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Courmayeur |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 1, 1954 |

| Place of death | Venice |