Dillenburg Castle

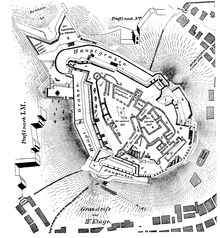

The Dillenburg Castle , which was expanded into a modern fortress (Festes Schloss) from the 1520s, was the main residence of the Counts of Nassau-Dillenburg . The residential and commercial buildings in particular were destroyed in the Seven Years' War in 1760, and in 1768 the fortifications were razed above ground. The casemates from the 16th century have been partially preserved. From 1872–1875, the Wilhelmsturm was built in the former upper courtyard according to plans by the builder Friedrich Albert Cremer .

history

The previous building of the Dillenburg Castle was a castle of the Counts of Nassau from the 12th century. After the excavations, especially in the 1950s, it had a roughly circular curtain wall around 30 meters in diameter, inside of which a free-standing tower with sides of 8 × 7.30 meters rose. Presumably it was a residential tower with half-timbered floors on a stone substructure, since remnants of clay and stove tiles were found in the fire rubble. This first castle was destroyed in the Dernbach feud around 1325/27.

Around the middle of the 15th century the old castle was rebuilt and expanded. Above all, it should now also be able to be defended against the increasingly effective firearms. In the years 1458–1462, a roundabout on a semicircular floor plan was under construction on the south side , with which the trench was initially to be secured on both sides with smaller firearms as a forward, independent work. Up until the 17th century, a half-timbered tower rose above a walled storey sunk in a ditch with loopholes. The Dillenburg artillery roundabout is a very early construction of this type.

In 1463/69 a Zwinger was named, that is, a strip of land placed in front of the main wall, which was secured by a lower front wall; it will have extended on the south and south-east sides and was later replaced by the large moat and the casemates . In 1463/64 a first rifle house ( armory ) was also mentioned.

From the second half of the 15th century, Dillenburg became the main permanent residence of the Counts of Nassau from the Ottonian line. Presumably the residential buildings and the castle chapel were also renewed at that time, but precise information is missing. At that time, the facility was certainly divided into an upper courtyard on the hilltop and the lower courtyard in the south and southeast, where the stables, forge and the new armory were later located.

In the decades after 1500 the political situation was particularly tense in the neighboring Landgraviate of Hesse. In the face of these threats, Count William the Rich of Nassau (ruled 1519 to 1559) began, at great expense, to convert his residence into a modern fortress. In larger territories, such tasks should be carried out by specialized state fortresses such as Ziegenhain and Gießen in Hessen; in the small county, the transitional form of the permanent castle was chosen, which continued to serve as the residence of the regent family.

First of all, around 1524, the “gros thurn zu Dillenbergk vor der kuchen” was broken off because it could have damaged the buildings if an artillery fire had fallen down. Under the master builder Ulrich (Utz) von Ansbach, who was also active in the metropolis of Nuremberg, the so-called High Wall was built on the city side from 1523 to 1536, which cost almost 200,000 guilders. On the main attack side in the south, high lining walls with earth backfilling were built on both sides of the older roundabout , which could withstand cannon fire. Here the building had casemate passages (still preserved) on its base with loopholes for handguns for trench defense, while the heavy artillery stood on an upper platform (later removed). Thanks to the main trench presented, only the upper part of the wall could be shot at by the enemy, while the casemates with the loopholes were in a blind spot. In connection with the new walls and ramparts, two more bulwarks were built, probably based on the new Italian invention of the bastion on a polygonal ground plan: in the west the so-called hunter's room and in the east the junker's room, both of which had extensive casemates. The Dillenburg official Gottfried Hatzfeld described all these systems in a poem in 1559.

Inside the palace, a new socket house ( armory ) was built on the west side of the lower courtyard in 1547 . Since 1553, the new building , which contained a large hall, was added to the older buildings in the inner courtyard .

On a view of the Dillenburg Castle, drawn around 1575 and later published by Braun and Hogenberg in 1617, the complex can be seen in the completed state of development. A drawing by Wilhelm Dilich from 1605 also gives a good impression .

During the Thirty Years War , the castle was able to withstand a siege due to its strong defenses.

The end of the fortress came in the Seven Years' War . In November 1759, Captain Otto Moritz von Düring occupied the castle with 100 men. In the last days of December 1759 and early January 1760, the Dill Valley and the city were occupied by the French. But on the night of January 7th to 8th, the troops of Duke Ferdinand von Braunschweig drove them out of the city. The Swiss Waldner Regiment was surprised and destroyed, 700 men were taken prisoner. As a result, the castle crew was enlarged and the troops provided with additional provisions. In June 1760, 5,000 French soldiers moved in and began to besiege the castle. The captain refused to surrender. So began the bombardment of the castle and on July 13, 1760 a haystack was set on fire. Since not enough water and crews were available to extinguish, most of the residential buildings burned down. In 1768 the fortifications were also razed by demolishing most of the aboveground components and filling the casemates. Major parts of the casemates were excavated in 1930–1934 and 1967/68 and are now partially accessible again.

Former equipment

Although almost all of the castle's furnishings were destroyed in the fire in 1760, many details have come down to us in older sources. An inventory of the castle from 1613 gives the most detailed account of the individual rooms and their furnishings at that time. This included numerous valuable tapestries, including the famous eight wall hangings woven in Brussels in 1531, belonging to the Nassau family. The family line was a gift from Count Heinrich von Nassau-Breda to his brother Count Wilhelm the Rich of Nassau-Dillenburg. While the carpets themselves have been lost since the late 17th century, the cardboard boxes by the Dutch painter Bernard van Orley have been preserved.

Historical descriptions

The Dillenburg Castle was described in 1559 by the count's official Gottfried Hatzfeld in a poem on the occasion of a triple wedding in the princely family that took place there:

"Vernim of the house opportunity,

I report to you with the warhait.

The church stan

against orient [east] herfur ghan is the most important thing.

An old salute to it,

Since one goes up the diaper [stair tower].

The vaulted room, close darbej,

How already painted sej,

proves the battle of Pavej [ Battle of Pavia (1525) ]

Whoever vil to say and write,

wil be

the worst . The kuch that always moves to the right,

to the left I found the bottlej.

A princely steadily building opposite

is not two high nor too low, which

one on the wapen kent,

and the newen sal itzt. On

it one the inscription list,

how old this baw is,

von golt is already flourishing,

the date according to it:

"birth After Christ as one zold

Dausend five hundred Vorgestalt

Fifty three [1553] probably bedracht

is disser new made building."

a gentleman close do the ground equal

Gebawet is quite artificial.

In the middle of space, a bronnen city,

the außghadt Roren by six.

That's kumpf dearly waved

Drum stand en nackent man und frawen

The spits put out the water.

From the square you walk to the summer house

Solicher baw has been made new

And

a dish uf Welschen [antique style] Wirth nhun called a vaulted room.

Dan you go uf the Lincke Handt,

So one cometh into the schreyberej,

The is gesindstub allernegst darbej,

Des kelners gemach that back home,

Dan goes to tw of wickets Auss,

a wide space [lower courtyard] there is findt,

Then the deputy according to order,

Gewelbet and supplied wol.

That in no less damage sol.

Schmidt and Megd Haus,

Dan you go out on the whale.

A garden is funny,

daruff vil fine beum ston.

Frembd gewechs are also a long way away,

some kind of hertz beger.

This house is also fastened

with walls and walls,

as it should be, surrounded

by a thick wall.

Drej boltweg [bulwarks] also has it next to it, which

one stands in the ditch [in the south],

since one goes to the hindmost gate [field gate].

The other is looking at the Marpach [so-called. Jägergemach in the west],

The third against the Hutt [Hüttenplatz] thut ghan [so-called. Junker's Chamber in the East].

A large grave on one side [in the south]

is Dieff and is of good breadth.

It has a strong whale,

eight guards keep watch early and late.

Obstacles included the same plan,

there already lind thut stan

The Heider Weltgen near bej

Leigt of all mountains free.

[...]

The Rundel [Südrondell] is up and the streichwehr.

And what more such things are,

the large rubble [in front of the rampart with lining wall on the west side] of the Marpach between

I itzo do not describe all.

Dan Dilnberg is so adorned

to defend himself and lust aedificirt,

If it doesn’t have a problem,

one Keyser's house who does it with honor. "

literature

- Rudolf Knappe: Medieval castles in Hessen. 800 castles, castle ruins and fortifications. 3. Edition. Wartberg-Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2000, ISBN 3-86134-228-6 , p. 418f.

- Elmar Brohl : The Dillenburg - its fortifications against firearms. In: Castles and palaces in the Westerwald. Historical defense and residential buildings between Sieg Lahn Dill and the Rhine. Hachenburg 1999, pp. 41-49.

- Elmar Brohl: Fortresses in Hessen. Published by the German Society for Fortress Research eV, Wesel, Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2013 (= German Fortresses 2), ISBN 978-3-7954-2534-0 , pp. 65–72.

- Walter Bauer: On the construction history of the Dillenburg in the Middle Ages and in modern times. Report on the investigations on the Dillenburger Schloßberg. In: Dillenburg 1568–1968. Contributions to the Nassau-Orange history. Dillenburg 1968, pp. 64-87.

- Severin Todt / Christof Rezk-Salama / Andreas Kolb: Virtual reconstruction and interactive exploration of the Dillenburg palace complex. In: Manfred Bogen / Roland Kuck / Jens Schröter (Eds.), Virtual Worlds as Basic Technology for Art and Culture? An inventory. Bielefeld 2009, pp. 119–138 Online version of the article (PDF; 2.4 MB)

- August Spieß: The Dillenburg Castle , Dillenburg 1869.

- Rolf Müller (Ed.): Palaces, castles, old walls. Published by the Hessendienst der Staatskanzlei, Wiesbaden 1990, ISBN 3-89214-017-0 , pp. 80f.

- Kurt von Duering, The Destruction of the Dillenburg Fortress in 1760 , 1917

- Carl Heiler: The fall of the Dillenburg castle. Lecture from June 28, 1935 on the occasion of the 175th anniversary of the destruction of the castle , 2nd edition, Verlag E. Weidenbach, Dillenburg 1953.

Web links

- Homepage of the Dillenburg Museum Association

- Project group Virtual Castle Dillenburg (virtual reconstruction of the castle building by a student working group at the University of Siegen)

- Casemates of the Dillenburg Castle

- Reconstruction drawing by Wolfgang Braun

- Literature about Dillenburg Castle in the Hessian Bibliography

supporting documents

- ↑ the chronology of the fortification measures, especially based on: Brohl 1999

- ^ Gottfried Hatzfeld: Chronicon Domus Nassavicae, manuscript, around 1584

- ^ Henry Lloyd, History of the Seven Years' War in Germany , Volume 3, p. 377, digitized

- ↑ HHStA (Wiesbaden) 3004, A 38. Quoted from: Hans-Jürgen Pletz-Krehahn: City and Castle Dillenburg after a description from the year 1559. In: Hans-Jürgen Pletz-Krehahn (Hrsg.): 650 years city of Dillenburg. A text and photo book on the anniversary of the city law of the Oranienstadt. Dillenburg 1994, pp. 37-39.

Coordinates: 50 ° 44 ′ 17.8 ″ N , 8 ° 17 ′ 7.5 ″ E