Distribution of income in Ireland

The income distribution in Ireland looks at the distribution of income in Ireland . Personal income distribution looks at how the income of an economy is distributed among individuals or groups (e.g. private households ). The equivalised disposable income is often used to examine the development of income distribution . According to Eurostat, Ireland had a Gini coefficient of 0.31 in 2017 , which is very close to the average in the European Union.

Distribution indicators - methods of representation

When developing the distribution of income, a distinction is usually made between market income and disposable income . Market income is the sum of labor and property income before state redistribution. The disposable income also takes into account all transfer payments (including unemployment and pension payments) and taxes. The comparison between the development of market income and disposable income enables an analysis of the redistribution mechanisms in an economy . The distribution of personnel is mostly measured by Eurostat on the basis of available equivalised income.

Median and mean of household disposable income

The graphic opposite describes the development of the median and mean value of disposable income over time. The median income is the income of the person who lies exactly in the middle of the income distribution, while the mean represents the average income of an economy . As the graph shows, the average equivalent income in Ireland in 2017 was € 27,006. In 1996 the disposable income was 10,085 euros. This corresponds to a nominal growth of approx. 67% within almost two decades. Adjusting for inflation shows a similar development in real median income. The average income of the EU countries in 2017 was 19,387 euros. This puts Ireland in 5th place in comparison.

In 2017, the median income in Ireland was € 22,879. 20 years earlier it was 9,173 euros. A positive development in nominal income can therefore also be observed here. Ireland ranks 7th in the EU average for median income and is therefore also in the upper ranks. The median for the EU is therefore 16,909 euros. If the mean value is greater than the median, this indicates an uneven distribution in favor of the upper half of the income. Such a distribution is called right skew .

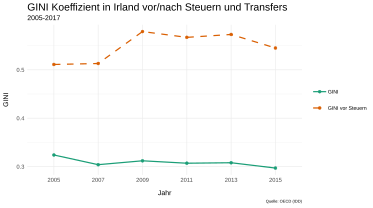

Representation with the Gini coefficient

The Gini coefficient is a measure used to determine the unequal distribution of income in a country. It enables comparison across national borders and is therefore often used as an indicator. Values between 0 and 1 describe the extent of inequality. A Gini coefficient of 1 means that one person has all the income in an economy . A value of 0, on the other hand, corresponds to an absolutely equal distribution between all people.

In 2015, according to OECD data, the Gini coefficient in Ireland before taxes and transfers was 0.545. In 2005 it was still 0.511. Within a decade, the unequal distribution of market incomes grew by over 3 percentage points. During the same period, however, inequality in income after taxes and transfers decreased by around 3 percentage points from 0.324 to 0.297. Growing inequality in market income, which goes hand in hand with decreasing inequality in disposable income, is an indication of greater redistribution by the state.

Share of the top 10%

This inequality measure describes the share of the richest 10% of the population in total national income. For the EU-27 this value has fluctuated around the 24% mark since 2005. In Ireland it was 25.2% in the same year. A decade later, the share of the top decile has decreased by one percentage point and is now 24.2%.

The increase before and after the economic crisis in 2008 can be clearly seen for both the EU-27 and Ireland itself. Since then, the share of the highest income 10% in Ireland has fluctuated around the corresponding figure for the top 10% in the EU-27 average.

Gender inequality

S80 / S20 ratio by gender

The S80 / S20 indicator describes the ratio of the income of the 20% of the population at the upper end of the income distribution (upper quintile ) to the 20% of the population at the lower end (lower quintile ). The higher this value, the more unevenly the income is distributed. For example, if the S80 / S20 ratio is three, the income of the richest 20% is three times that of the poorest 20%.

In 1995 the ratio was around 5 for both sexes, but in 2017 it was only around 4.5. With the exception of the late 1990s and 2005, there are no major differences in gender. According to this indicator, inequality tends to be slightly higher for men than for women. The aggregated S80 / S20 ratio of women and men in 2017 was around 4.6 and is therefore lower than the EU average of 5.1.

Unadjusted gender pay gap

The unadjusted gender pay gap (GPG) is the gender-specific wage gap . The average hourly wages of women and men are compared without taking into account differences in job profiles in an economy. In the EU-27 average, men therefore have an average of 17% higher wages than women. In Ireland, the GPG is just under 14%, but after a decrease in 2010 it has been increasing again since 2012.

Nevertheless, the unadjusted wage gap in Ireland between men and women is below average in comparison with the EU. So gender inequality is lower in Ireland compared to other EU countries. While the difference between the EU27 and Ireland was just under 5 percentage points in 2008, it was only 3.5 percentage points in 2014.

Regional inequality

Disposable household income by region

Average household disposable income by region corresponds to the average household income at the level of the NUTS-2 regions. Ireland is divided into three NUTS-2 regions in 2016. The Eastern and Midlands region, in which the capital Dublin is also located, leads the way with an average disposable household income of around 16,500 euros. The region with the lowest incomes is Northern and Western (approx. 13,100 euros). The Southern region lies in between with an average income of around 15,000 euros.

At-risk-of-poverty rate by region

The at- risk-of-poverty rate is a measure of relative poverty and describes the proportion of people whose equivalised disposable income is below 60% of the median equivalised income. It is therefore an indicator of the extent to which the development of income distribution is at the expense of those with the lowest incomes. The regional representation shows the at-risk-of-poverty rate by NUTS-2 regions in 2011. Compared to the current NUTS-2 categorization, the Republic of Ireland was divided into only 2 regions at the time, with the northern region having a significantly higher at-risk-of-poverty rate. This confirms the observations of average incomes, which in the north and west are well below those in the west and south even a few years later.

Background and development

The "Celtic Tiger" (1994-2007)

Between 1994 and 2000, Ireland had above-average economic growth of around 7% for industrialized countries , one of the highest growth rates in the OECD . This boom gave Ireland the title Celtic Tiger, based on the rapidly growing economy of the tiger states of Southeast Asia . The strong growth was attributed to foreign direct investment and the flourishing construction industry. Unemployment fell from 12% to 4% between 1996 and 2000 and remained at that level until 2006. The distribution of income by market income became more equal during this period. This can be explained, among other things, by the fact that the hourly wages of the lower income brackets rose more sharply than those of the upper income brackets relative to their original value.

Real economic growth fell from 2000 onwards, but remained at a high level of 4 to 6% until 2007. During this period a domestic real estate bubble emerged from which the upper income brackets and especially the top 10% benefited. This could also explain why the distribution of income became more unequal again by the beginning of the crisis in 2008. A national minimum wage was introduced in 2000, but this did not prevent inequality from growing. Paradoxically, people on the minimum wage were largely found in the upper half of household incomes, reducing the effectiveness of the minimum wage as a means of redistribution.

The financial crisis (2008-2013)

In 2008, the global economic and financial crisis hit Ireland hardest of all OECD countries in terms of the decline in gross national product. The bursting of the real estate bubble resulted in a far-reaching banking crisis in Ireland. The attempt to cover the refinancing needs of the domestic banks with taxpayers' money or through the international financial market failed. In 2010, Ireland became the first country to come under the recently founded Euro rescue fund (EFSF) and between 2011 and 2013 was supported with funds from the EU and the IMF . The recession had serious consequences for the population, including the unemployment rate, which rose from 4.5% to 14.7% between 2007 and 2010. The Irish government's consolidation policy (measures to reduce the budget deficit ) has been accompanied by a series of austerity measures with far-reaching consequences for the disposable income of Irish households. The first wave of measures included, among other things, tax increases, a reduction in child and unemployment benefits, and an increase in the cap on social security contributions . In order to cushion the effects on low incomes, the amount of transfer payments was increased to compensate. As a result, household disposable income fell more slowly than gross income (−7.5% and −11.1%, respectively).

The Gini index for market personnel income increased while the Gini index for equivalised disposable income remained relatively stable over the crisis. This is attributed, among other things, to the progressiveness of the tax and benefit system. Accordingly, even the strict austerity measures did not have a negative impact on inequality in disposable income. However, especially from 2013 onwards, these influenced the absolute level of incomes and poverty rose sharply. Ireland is the OECD country with the highest inequality in terms of market income in 2010. If transfers are taken into account, it is always better than the OECD average.

Consolidation (2013/14 - today)

Ireland was the first country to withdraw from the EFSF in 2013 and has since been considered a model example of crisis management in the euro area. According to the European Stability Mechanism , Ireland was the fastest growing economy in the EU three years after it left the EFSF. In fact, the country had a nominal GDP growth of 34.7% in 2015. However, since a large part of this growth can be traced back to the settlement of foreign companies, including some letterbox companies , it is not possible to infer any actual increase in economic activity. A correspondingly adjusted index (Modified GNI) measures significantly lower nominal economic growth of 11.9% for Ireland for 2015. These adjusted growth figures nevertheless indicate an end to the recession in Ireland. Unemployment fell from 14% in 2011 to 8% in 2017. The OECD is forecasting a further decrease in unemployment in the coming years. Young, low-skilled people are still badly affected by unemployment. Equivalised disposable income inequality has been falling since 2014. Income inequality by market income remains high in Ireland. However, the welfare state's reduction in inequality is greater than that of any other OECD country.

Web links

- Home - CSO - Central Statistics Office. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- Database - Eurostat. Retrieved January 10, 2019 .

- European Anti Poverty Network Ireland. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- Economic Survey of Ireland 2018 - OECD. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Eurostat: Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income. Source: SILC. Retrieved July 16, 2019 .

- ↑ Equivalent disposable income. In: Eurostat. Retrieved January 19, 2017 .

- ↑ adjusted for inflation using HICP = 2015

- ^ Federal Statistical Office: Distribution of Income. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Eurostat: Disposable income of private households by NUTS 2 regions. Retrieved May 8, 2019 .

- ↑ Eurostat: At- risk-of-poverty rate. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d Brian Nolan, Bertrand Maitre, Sarah Voitchovsky: Wage Inequality in Ireland's “Celtic Tiger” Boom . In: The Economic and Social Review . tape 43 , 1, Spring, 2012, ISSN 0012-9984 , p. 99-133 .

- ↑ Denis O'Hearn: Inside the Celtic Tiger: The Irish Economy and the Asian Model . Pluto Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-7453-1288-0 .

- ↑ Ella Arensman, Paul Corcoran: Suicide and employment status during Ireland's Celtic Tiger economy . In: European Journal of Public Health . tape 21 , no. 2 , April 1, 2011, ISSN 1101-1262 , p. 209-214 , doi : 10.1093 / eurpub / ckp236 .

- ^ Donal O'Neill: Low Pay and the Minimum Wage in Ireland . In: Minimum Wages, Low Pay and Unemployment . Palgrave Macmillan UK, London 2004, ISBN 978-1-349-51859-3 .

- ↑ Stephen P. Jenkins, Andrea Brandolini, John Micklewright, Brian Nolan: The Great Recession and the Distribution of Household Income . OUP Oxford, 2012, ISBN 978-0-19-165029-1 .

- ↑ a b Ireland | European Stability Mechanism. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ^ Donal O'Neill, Niamh Holton: The Changing Nature of Irish Wage Inequality from Boom to Bust . In: The Economic and Social Review . tape 48 , 1, Spring, March 28, 2017, ISSN 0012-9984 , p. 1-26 .

- ^ A b Olivier Bargain, Tim Callan, Karina Doorley, Claire Keane: Changes in Income Distributions and the Role of Tax-Benefit Policy During the Great Recession: An International Perspective . In: Fiscal Studies . tape 38 , no. 4 , 2017, ISSN 1475-5890 , p. 559-585 , doi : 10.1111 / 1475-5890.12113 .

- ↑ Michael Savage, Karina Doorley, Tim Callan: Inequality in EU Crisis Countries: How Effective Were Automatic Stabilisers? ID 3158145. Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY 2018.

- ↑ Alberto González Pandiella, Yosuke Jin, David Haugh: Growing together . April 19, 2016, doi : 10.1787 / 5jm0s927f5vk-en .

- ↑ a b Economic Survey of Ireland 2018 - OECD. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey. In: Eurostat - Data Explorer. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .