Distribution of income in Hungary

The income distribution in Hungary considers the distribution of income in Hungary. When analyzing the distribution of income, a distinction is generally made between the functional and the personal income distribution discussed here. Personal income distribution looks at how the income of an economy is distributed among individuals or groups (e.g. private households ), regardless of the source of income from which it originates. The personal distribution of income is mostly measured by Eurostat on the basis of equivalised disposable income, which describes the disposable income of the members of a household at the individual level. When interpreting statistical data, the different uses of the term income must be taken into account, because a distinction must be made between gross income , income , taxable income and net income or disposable income .

In 2017, the Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income for Hungary was 28.1, making Hungary one of the most evenly distributed countries in Europe.

Development of income distribution

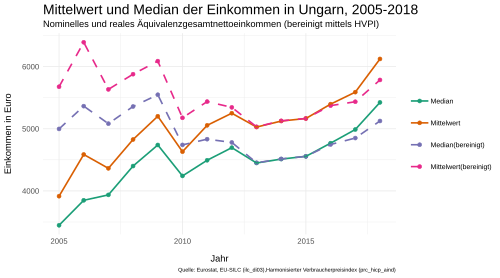

Since 2005 the average and median disposable income has increased in Hungary. The average disposable income in 2017 was € 5,589 and the median income for the same year was € 4,988. While the inequality in income distribution in Hungary tended to decrease between 2005 and 2010, it has increased steadily since 2010. The Gini coefficient increased from 24.1% in 2010 to 28.1% in 2017.

Income inequality indicators

The indicators of income inequality are used to quantify the extent of income inequality based on the distribution of disposable income in Hungary . This means the distribution of income after direct taxes, social contributions and including public (e.g. social assistance , unemployment benefits ) and private (e.g. maintenance ) transfers.

Average and median income

The average disposable income in Hungary has risen steadily from 2005 to 2018 with few irregularities. There was a small slump shortly after the financial crisis of 2008. Seen in this light, the equivalised disposable income has improved from € 4,000 in 2005 to € 6,100 in 2018.

The median income is below the average income in Hungary, which means that the income distribution is skewed to the right. A large difference between median and average income indicates a highly unequal distribution of income. The median disposable income for Hungary was € 3,500 in 2005 and approached € 5,500 in 2018. The developments in average and median incomes show the slump in incomes during the financial crisis of 2008 - both have declined. The average income was always above the median income in Hungary.

If one looks at real incomes, adjusted with the harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP), one can see that real average incomes are stagnating or are relatively constant between € 5,000 and € 6,500 in Hungary. The real median incomes are between € 4,500 and € 5,500.

Gini coefficient of disposable income

A popular means of illustrating the distribution of income is the Gini coefficient . A Gini coefficient of 0 corresponds to an absolutely equal distribution of income, while a Gini coefficient of 1 would mean a situation of absolute inequality in which one person or a household has the entire income.

The first data were collected by the OECD in 1991 and show a Gini coefficient for Hungary of 0.273. From then on this value rose steadily over the years and reached its preliminary high in 1994 with a value of 0.299. This high was only exceeded in 2003 with 0.303, which was followed by another downturn. The last period observed showed an increase in the Gini coefficient again. In 2012 this was 0.29.

The comparison of the OECD data collection with that of the Eurostat EU-SILC survey shows clear differences in the interpretation of the Gini coefficient of disposable income for Hungary . Starting with a coefficient of 0.26 in 2001, this is far below the value obtained from the OECD data collection (0.293). After this value fell steadily until 2002, it rose rapidly and reached a maximum value of 0.333 in 2006. The Gini coefficient again fell just as quickly until 2010. From then on, a steady rise in the index was observed. In 2018, Hungary's Gini coefficient of disposable income was 0.287.

A comparison with the EU27 average and the neighboring countries Austria and Slovakia shows that the Gini coefficient is lower than the average for the EU27 countries. However, the index has risen above the values of Austria and Slovakia in recent years. This can be interpreted as increasing inequality compared to the neighboring countries mentioned, starting with 2010. The sudden jump in the Gini coefficient in 2006 according to EU-SILC data is still unexplained.

Income quintile ratio (S80 / S20)

Another way to look at income inequality is the S80 / S20 ratio. This compares the income of the richest 20% of the population (top quintile or 80th percentile ) with the income of the poorest 20% of the population (bottom quintile or 20th percentile) and puts this into relation.

If one looks at the evaluation of the EU-SILC survey, it can be seen that the values for women and men run almost parallel. With the exception of 2018, men consistently achieve higher values. At the highest point in 2006, the earnings quintile ratio for men was 5.7. This means that men in the top quintile have an income 5.7 times higher than those in the bottom quintile. By contrast, women in the top quintile have an income 5.3 times higher than women in the bottom quintile at the same time.

The course of the income quintile ratio showed a high swing in 2006, but followed by a downturn until 2010, which can be interpreted as a reduction in the inequality. In the following years, a renewed increase can be observed, which shows an increase in inequality.

The higher values for the group of men up to 2017 show that there was a somewhat higher unequal distribution between the top and bottom quintiles. A change in this trend has been observed since 2013: in 2018, for the first time, the inequality among women is higher than among men. Future surveys will only show whether this development will continue.

The generally increasing inequality is justified by the fact that, after the economic crisis, capital income fell particularly sharply relative to labor income. As with the Gini coefficient, the strong increase in the income quintile ratio (S80 / S20) for 2006 cannot be satisfactorily justified.

Gender pay gap

The gender pay gap , usually called the gender pay gap , illustrates the differences in income between men and women. The gender pay gap was also determined with the EU-SILC data collection according to NACE2 sectors for all member states of the European Union . There are interesting developments in the industry, construction and services sector:

In 2008 the difference between the sexes in Hungary was 17.5% and thus only slightly above the EU27 average of 17.3%. In the sector mentioned, Hungarian women earn 17.5% less than their male colleagues at this point in time. After initially falling, the earnings gap widened in 2009 until it reached a maximum of 20.1% in 2012. From there on, the gender pay gap falls to 14% by 2015, which is 2.6 percentage points below the average for the EU27 countries. A minimal increase to 14.2% can be seen in 2017.

Top 10% share of total income

The top 10% share describes the share of total national equivalised income that the top 10% of the population receive. In Hungary, the top 10% of the population had 22% of total national equivalised net income in 2017. In the weighted EU average, this share was 23.8% in 2017. Hungary is below the EU average in this respect - labor income is more evenly distributed in Hungary compared to other OECD countries. At the same time, there has also been a steady increase in the top 10% share of total income since 2010 - income inequality in Hungary has increased since then.

| year |

Average

Income in EUR |

Median

Income in EUR |

Gini

coefficient |

Income quintile

ratio (S80 / 20) |

Share of the top 10%

on total income (Hungary) |

| 2005 | 3,915 | 3,447 | 0.276 | 4.0 | 24.1 |

| 2006 | 4,586 | 3,849 | 0.333 | 5.5 | 23.7 |

| 2007 | 4,363 | 3,936 | 0.256 | 3.7 | 24.0 |

| 2008 | 4,827 | 4,400 | 0.252 | 3.6 | 24.6 |

| 2009 | 5,201 | 4,739 | 0.247 | 3.5 | 24.2 |

| 2010 | 4,631 | 4,241 | 0.241 | 3.4 | 24.0 |

| 2011 | 5,055 | 4,493 | 0.269 | 3.9 | 24.2 |

| 2012 | 5,250 | 4,696 | 0.272 | 4.0 | 23.8 |

| 2013 | 5,027 | 4,449 | 0.283 | 4.3 | 23.9 |

| 2014 | 5.124 | 4,512 | 0.286 | 4.3 | 24.0 |

| 2015 | 5,165 | 4,556 | 0.282 | 4.3 | 24.1 |

| 2016 | 5,396 | 4,768 | 0.282 | 4.3 | 23.8 |

| 2017 | 5,589 | 4,988 | 0.281 | 4.3 | 23.9 |

Regional inequality

In Hungary, among other things, income is unevenly distributed regionally. In the north-west of Hungary, the disposable household income per capita is significantly higher than in the north-east. For 2016, the statistics show values between 9,200 and 11,000 purchasing power standards (PPS) per person and year for the average disposable household income, with 11,000 PPS being reached in Pest County and the lowest values of 9,200 PPS and 9,300 PPS in the north-eastern regions of Northern Hungary and Northern Great Can be reached.

A picture similar to that of the distribution of disposable household income is also found for the population at risk of poverty and social exclusion. In regions where residents have higher disposable household incomes, the risk of poverty is also lower. The proportion of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion is between 12.5% in western Transdanubia and 32.9% in northern Hungary . For comparison: the value for the whole of Hungary is 19.6%.

Although there is still great inequality between regions, it has decreased in recent years.

Economic policy background

Rise and Fall of the Post-Socialist Model (1989-2010)

After the end of the Soviet Union in 1989, Hungary's economic hopes were on small and medium-sized enterprises that emerged from the semi-market economy system of the Kadar era. But they could not withstand global competition and the industrial sector in Hungary collapsed, which caused a social catastrophe. One million of a total of four million jobs were lost in this way and the unemployed were dependent on state social benefits. Attempts have been made to address this problem by attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). The foundation stone for this had already been laid in the semi-open market economy Kadar regime. Thus, in the early 1990s, Hungary became one of the preferred destinations for FDIs. Measures for integration into the European Union and the establishment of institutions based on the “acquis communautaire” of the European Union ensured a further economic delay. In the course of the EU's eastward expansion, Hungary, as the most important FDI location, lost its relevance and faced increasing competition from other Central and Eastern European countries. In a more strongly polarized party system, economic pressure should pave the way for political populism and heated election campaigns.

Between 2002 and 2010 the MSZP - SZDSZ coalition party ruled in Hungary. Its economic policy program was aimed at promoting welfare state services. During this period, the government introduced a 50% pay increase for the 600,000 civil servants and abolished the taxation of the minimum wage. She also increased the family allowance by 20% and extended it to a 13th month. Furthermore, in a test phase, the 13th month pension was introduced for three million pensioners. The interventions were mainly financed by public debt, due to a lack of increased public revenues, and by 2007 raised the general government debt ratio from 52% to 65%.

The new economic model: selective nationalism and selective welfare state (from 2010)

FIDESZ won the 2010 elections and secured a constitution-changing, 2/3 majority in parliament with just over 50% of the votes. Since then, the government in Hungary has changed the “rules of the game” in such a way that the elections are free, but not fair. The most important democratic rules were systematically changed in favor of the ruling party, increasing their chances of staying in office. The powers of the Constitutional Court were restricted, most of the media were subjected to state control and their rights severely curtailed by the media law.

The economic policy concept of FIDESZ is described as selective nationalism. It is based on the state protectionism of local actors from the effects of the world market. This concept would not be fully feasible for Hungary, as an EU member and as a small country without large companies. Economic nationalism is mainly practiced in sectors that depend on government contracts. In these sectors, the role of key domestic companies is promoted by the government. In addition, tough regulations are intended to ensure that more (foreign) private companies are transferred to domestic providers and the Hungarian state. In the other sectors such as B. the industry where foreign direct investments play an important role, a neo-liberal policy is introduced. The flexibilization of the labor market and cuts in social benefits are further signs of the neoliberal “work-fare” model.

In the tax debate of economic nationalism, the top 10% of taxpayers benefited from the generally introduced flat tax of 16%. The tax burden for those on lower incomes increased considerably. At the employer-employee relationship level, the trade unions have been weakened, which, together with labor market regulation, is intended to attract further foreign investments into the country. Overall, this concept remains very contradictory, on the one hand incentives are created and on the other hand major obstacles are built up. Low wages, a weak value creation potential of the domestic market-oriented economy, the low qualification level of the employees and the necessary lack of public investment in education and training as well as unfavorable demographic development and risks in the pension system are some of the challenges for a sustainable and strong economy in Hungary.

Great Depression (2008-2010)

The global economic crisis of 2008 had many negative consequences for the people and the economy in Hungary. For example, the national debt ratio rose to a record high of around 80% shortly after the crisis. Since then this value has decreased and in 2019 it was 67.5%. With the financial crisis, public spending increased - a large number of people were employed in the public sector and this has contributed to economic growth and easing the recession. The Great Depression also had a negative impact on the unemployment rate - it was around 12% in 2009 and higher than before. A distinction must also be made between the various phases of the economic crisis. In the second half of 2008, the crisis was mainly characterized by losses in the money market. These losses particularly affected those who held stocks and savings. However, this phase is not directly visible in the income distribution statistics. The next crisis period affected households through two channels: On the one hand, through processes in the money market in connection with the unfavorable development of the forint exchange rate, which had a direct impact on those who had foreign currency loans for buying a home or car. On the other hand, through the fall in employment and the rise in unemployment. The effects of the last phase of the crisis were realized in the context of the austerity measures announced in spring 2009 (cuts in public expenditure for the population and the welfare role of the state). In this context, pension expenses (withdrawal of the 13th monthly pension), family allowances and social allowances (maximum number of allowances per household) were reduced.

labour market

The overall unemployment rate was around 8% in 2014 and has fallen in recent years, approaching the OECD average. At around 12% shortly after the financial crisis, it was well above the OECD average of around 8%. Youth unemployment (measured in NEET ) is around 21%, above the OECD average of 17%. The share of long-term unemployed (1 year +) is around 48%, well above the OECD average of 33%. The participation rate for women is around 61%, which is one of the lowest among the OECD countries - behind Poland and Slovakia. The wage gap between women and men in Hungary is around 5%, one of the smallest among the OECD countries. The minimum wage relative to the median wage is around 55% and is therefore relatively high within the EU. The productivity rate of workers has decreased in recent years, and this decrease has had consequences for the distribution of income.

education

Hungarian pupils do poorly in international school performance surveys compared to other OECD countries. In addition, the differences in performance between schools are very large - well above the OECD average. The proportion of teachers in the population is well above the OECD average. Many have no prospect of a job. In addition, teachers are also paid very poorly - compared to other OECD countries. The percentage of the population aged between 24 and 35 with tertiary education in Hungary is around 20% and this figure is one of the lowest among OECD countries - the OECD average is 32%.

Public social spending

Since the financial crisis of 2008, the proportion of employees in the public sector in Hungary has increased - for 2014 alone, the increase was around 125,000 employees. This also contributes to economic growth. Government spending relative to GDP is around 50%, well above the OECD average of 45%.

bibliography

- Atkinson, Antony B. "After Piketty ?." The British Journal of Sociology 65.4 (2014): 619-638.

- Canberra Group. Expert group on household income statistics: final report and recommendations . Canberra Group, 2001.

Ward, T., Lelkes, O., Sutherland, H., & Tóth, IG (2009). European inequalities: Social inclusion and income distribution in the European Union.

Web links

- OECD Income Inequality: https://data.oecd.org/inequality/income-inequality.htm#indicator-chart

- Eurostat: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat

- World Inequality Database: https://wid.world/

Individual evidence

- ↑ Definition: personal income distribution. Retrieved August 19, 2019 .

- ^ Income and living conditions (ilc). Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Average and median income by age and gender - EU-SILC survey (icl_di03). Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income Source: SILC (ilc_di12). Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ a b HICP (2015 = 100) - Annual data (average index and rate of change) (prc_hicp_aind). EUROSTAT, accessed on May 7, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey (ilc_di12). Retrieved May 8, 2019 .

- ^ Income and Poverty - OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD). Retrieved May 8, 2019 .

- ↑ a b OECD: INCOME DISTRIBUTION DATA REVIEW - HUNGARY . 2012, p. 180 .

- ↑ a b c d S80 / S20 income quintile ratio by gender and by age group - EU-SILC survey (ilc_di11). Retrieved May 8, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Gender-specific earnings gap, without adjustments, according to NACE Rev. 2 activity - methodology: wage structure survey - EU-SILC survey (earn_gr_gpgr2). Retrieved May 8, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Income distribution according to quantiles - EU-SILC survey (ilc_di01). Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Disposable income of private households, by NUTS 2 regions. EUROSTAT, accessed on May 6, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d Publishing, OECD .: Reforms for Stability and Sustainable Growth An OECD Perspective on Hungary. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2008, ISBN 1-281-71986-2 .

- ↑ a b Population at risk of poverty or social exclusion by NUTS regions. EUROSTAT, accessed on May 6, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Tóth, Andreas: The end of the story of suffering? The rise of selective economic nationalism in Hungary. Ed .: Split integration: The triumph of failed ideas in Europe – revisited: Ten country studies, Hamburg, VSA, 209-226. 2014.

- ↑ Palócz Éva: Makrogazdasági folyamatok és fiskális politika Magyarországon nemzetközi összehasonlításban. (PDF) Retrieved February 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Az államháztartás adóssága (1995-2016). Retrieved February 27, 2019 .

- ^ Andreas Burth: HouseholdSteuerung.de :: Debt clock on the national debts of Hungary. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Hungary: National debt from 2008 to 2018 in relation to gross domestic product. Retrieved February 20, 2019 .

- ↑ Szívós Péter, Tóth István György: Jól nézünk ki (… ?!) Háztartások helyzete a válság után. (PDF) Retrieved February 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Jövedelemeloszlás a konszolidációs csomagok és a válságok közepette Magyarországon. Retrieved February 27, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Economic Survey of Hungary 2016 - OECD. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .