Distribution of income in Spain

The income distribution in Spain considered the personal distribution of income in Spain . The personal income distribution considers how the income of an economy is distributed among individuals or groups (e.g. private households ).

Income inequality in Spain has tended to decrease over the past few decades, but there have also been periods of increase: after the recession in 1993 and also in the wake of the global economic crisis from 2007 , income inequality rose.

In 2017, the Gini index of equivalised disposable income for Spain was 34.1%. Compared with the countries of the European Union, Spain ranks 24th, so income in Spain is relatively unevenly distributed.

Distribution indicators - methods of representation

Various indicators and methods are used to measure the distribution of income in a country.

The personal distribution of income is measured by Eurostat on the basis of the equivalised disposable income , which reflects the disposable income of the members of a household at the individual level. In addition, the Gini index is used for international comparisons and OECD data is used for comparing inequality between metropolitan areas in Spain .

Average and median income

The average annual equivalised disposable income in Spain was € 16,392 in 2017. The median income in 2017 was € 14,207. 50% of the households had an annual income of more than € 14,207 and 50% less. An average income above the median income means that the disposable income is distributed skewed to the right . After 2008, the average and median income initially decreased, but they have increased again since 2014. It must be taken into account that this is the nominal income, i.e. it is not adjusted for inflation.

Both the nominal and the adjusted mean (around the HICP ) of incomes in Spain will increase until 2009. From 2009 to 2014 you can see a downward trend in the (adjusted) mean until the values increase again from 2014 onwards.

The nominal and real median income in Spain are very similar. From 2004 to 2009 there was an increasing trend in median income. The median income in Spain fell from 2009 to 2014 until it rose again from 2014 onwards.

Gini coefficient

In 2017, Spain's Gini index was at a relatively high level compared to the EU, only Latvia , Lithuania , Serbia and Bulgaria had a higher Gini index during this period, according to Eurostat . On average, the Gini index of the EU countries in the period from 2005 to 2017 was always below that of Spain, so income inequality in the EU was lower on average. In addition, Spain's Gini index was relatively high compared to the neighboring countries of France and Portugal (see also income distribution in Portugal , income distribution in France ).

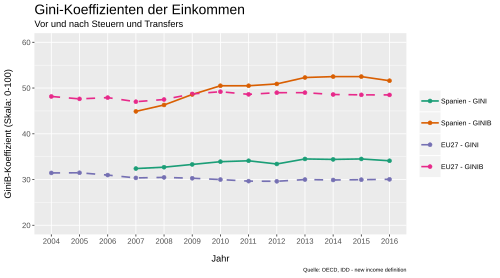

Based on the OECD data, it can be seen that the disposable income before taxes and government transfers show a Gini index of 45% for 2007 and 52% for 2016. The considerable difference between disposable income before and after taxes and transfers can be interpreted as a yardstick for high government income redistribution. After taxes and transfers, Spain's Gini index was 32.5% for 2007 and 34% for 2016.

Income quintile ratio (S80 / S20)

The income quintile ratio describes the ratio of the total disposable income of the richest 20% of the population to the total disposable income of the poorest 20% of the population. In 2017 the income quintile ratio was 6.6. The 20% of the population with the highest income had an equivalent income that was 6.6 times that of the 20% of the population with the lowest income. The quintile ratio of disposable incomes in Spain has increased since 2008, but has decreased again since 2014. In the observed 10 years, the income quintile ratio in Spain was always well above the (weighted) EU average and thus shows a higher income inequality for the examined period than in other EU countries.

Top 10% share of total income

The top 10% share describes the share of total national equivalised income held by the 10% of the population with the highest disposable income . In Spain, the richest 10% of the population had 24.4% of total national equivalised net income in 2017. In the weighted EU average, this share was 23.8% in 2017. This means that the highest 10% of incomes in Spain are relatively slightly higher than the EU-27 average.

At-risk-of-poverty rate

The at- risk-of-poverty rate in Spain has risen slightly over the past few years and was 21.6% in 2017. This means that this proportion of the population had less than 60% of the median equivalised income. The at-risk-of-poverty rate in the weighted EU-27 average in 2017 was 16.9% below the Spanish one, which means that there are more people at risk of poverty in Spain.

| Table 1: Income distribution indicators in Spain | ||||||

| year |

Average

Income (in €) |

Median

Income (in €) |

Gini

Index (in%) |

Income quintile

ratio (S80 / S20) |

Share of the top 10%

on total income |

At risk of poverty

quote |

| 2017 | 16,392 | 14,207 | 34.1 | 6.6 | 24.4% | 21.6% |

| 2016 | 15,842 | 13,685 | 34.5 | 6.6 | 24.9% | 22.3% |

| 2015 | 15,408 | 13,352 | 34.6 | 6.9 | 24.8% | 22.1% |

| 2014 | 15,405 | 13,269 | 34.7 | 6.8 | 24.7% | 22.2% |

| 2013 | 15,635 | 13,523 | 33.7 | 6.3 | 24.5% | 20.4% |

| 2012 | 16,118 | 13,864 | 34.2 | 6.5 | 24.7% | 20.8% |

| 2011 | 16,280 | 13,929 | 34.0 | 6.3 | 25.0% | 20.6% |

| 2010 | 16,924 | 14,605 | 33.5 | 6.2 | 24.6% | 20.7% |

| 2009 | 17,042 | 14,795 | 32.9 | 5.9 | 24.4% | 20.4% |

| 2008 | 16,190 | 13,963 | 32.4 | 5.6 | 24.2% | 19.8% |

| 2007 | 13,265 | 11,644 | 31.9 | 5.5 | 23.6% | 19.7% |

| 2006 | 12,632 | 11,111 | 31.9 | 5.5 | 23.7% | 20.3% |

| 2005 | 11,987 | 10,417 | 32.2 | 5.5 | 23.8% | 20.1% |

| 2004 | 11,546 | 10,200 | 31.0 | 5.2 | 23.3% | 20.1% |

Regional inequality

Regional distribution of disposable household income

Regional inequality examines how income and wealth are distributed among the various regions within a country.

Central Spain ( Castile-La Mancha ) and Catalonia were the regions with the highest incomes (€ 18,240 - € 19,900) for the period examined (2016), while Galicia , Aragon , Navarra and Madrid were the regions with the lowest incomes (€ 11,600 - € 13,260). In between were the regions in the east and west of the country, i.e. the Valencian Community , Estremadura and Castile (€ 14,920 - € 16,580). The north and south ( Cantabria and Andalusia ) were also low-income regions (€ 13,260 - € 14,920).

| city | Share of the total population (%) | Unemployment among people over the age of 15 (%) | GDP per capita, real ($ in PPP ) | GDP / capita in relation to national GDP / capita (%) |

| Alicante | 1 | 26th | 23,787 | 77.6 |

| Barcelona | 8.6 | 20th | 43,858 | 143.1 |

| Bilbao | 2.2 | 17.4 | 37,808 | 123.4 |

| Cordoba | 0.8 | 33.6 | 22,170 | 72.3 |

| Coruna | 0.9 | 20th | 27,657 | 90.2 |

| Donostia - San Sebastian | 0.7 | 14.3 | 39,899 | 130.2 |

| Elche / Elx | 0.5 | 26th | 25,788 | 84.1 |

| Gijon | 0.6 | 21.1 | 25,478 | 83.1 |

| Granada | 1.2 | 35.9 | 23.208 | 75.7 |

| Las Palmas | 1.3 | 34.1 | 25,299 | 82.5 |

| Madrid | 13.9 | 19th | 42.102 | 137.3 |

| Malaga | 1.8 | 32.6 | 22,983 | 75 |

| Marbella | 0.6 | 32.6 | 23,426 | 76.4 |

| Murcia | 1.3 | 26.6 | 25,881 | 84.4 |

| Oviedo | 0.7 | 21.1 | 28,114 | 91.7 |

| Palma de Mallorca | 1.4 | 20th | 35.005 | 114.2 |

| Pamplona | 0.8 | 15.7 | 38,629 | 126 |

| Santa Cruz de Tenerife | 1.1 | 30.1 | 27,335 | 89.2 |

| Santander | 0.8 | 19.4 | 28,189 | 92 |

| Zaragoza | 1.6 | 20.8 | 34,712 | 113.3 |

| Seville | 3.3 | 32.8 | 25,148 | 82 |

| Valencia | 3.6 | 25.4 | 28,637 | 93.4 |

| Valladolid | 0.9 | 18.1 | 31,338 | 102.2 |

| Vigo | 1.2 | 24.7 | 25,685 | 83.8 |

| Vitoria | 0.6 | 17.2 | 47,698 | 155.6 |

| Source: OECD, CITIES (2014) | ||||

The data in the table relate to 2014 and show the differences in unemployment among the 15 and over and the differences in GDP per capita in Spanish cities. Barcelona , Bilbao , Donostia - San Sebastian , Madrid , Palma de Mallorca , Pamplona , Saragossa , Valladolid and Vitoria have above-average incomes compared to the value for all of Spain. Cordoba , Malaga , Granada and Alicante are among the cities with the lowest GDP / capita compared to the national GDP / capita. The cities with the highest GDP / capita usually also have the lowest unemployment rates, while the cities with the lowest GDP / capita tend to have the highest unemployment rates.

Regional risk of poverty

The regions of Galicia and Asturias in the north are those with the highest proportion of the population at risk of poverty (38% - 44%). The lowest risk of poverty is measured in the Valencian Community , Murcia , Castile-La Mancha and Estremadura (14% - 20%). Madrid and Catalonia have an at-risk-of-poverty rate of 20% - 32%.

gender gap

Income quintile ratio (S80 / S20) by gender

The income quintile ratio indicates the ratio of the total income of the 20% of men or women with the highest income (top quintile) to the total income of the 20% of men or women with the lowest income (bottom quintile). The income quintile ratio for both men and women increases over time. In 2013, both time series fell briefly before assuming an inconsistent course. The last observation in 2017 shows that the income quintile ratio of men is higher than that of women.

Gender Pay Gap in Spain

The development of the gender pay gap in Spain based on the EU-SILC data for the private sector shows a negative trend (as does the EU-27 average), with the Spanish gender-specific wage gap fluctuating more around this downward trend. In 2017 the GPG was 15%, which means that Spaniards earn on average 15% more than Spanish women.

backgrounds

In the 20th century, Spain was shaped by the transition from dictatorship to democracy. In terms of inequality indicators, Spain falls into the lower ranks among the EU member states, partly due to the labor market and the education system. Within the EU, Spain has the fifth largest number of inhabitants and at the same time also the fifth largest gross national product , but if you look at the gross domestic product per capita in purchasing power parities , you can see that at 92 points it is below the EU-27 average of 100 points. Inequality itself has tended to decrease since the end of the dictatorship in 1975 until 2018, but this tendency was reversed in times of crisis. In the mid-1990s, Spain fell into recession. The Gini coefficient, which had been falling until then, rose again from this point in time. After a subsequent phase in which the Gini coefficient fell again, the income inequality indicator changed again from the start of the global financial crisis in 2007 and showed increasing inequality.

labour market

The Spanish labor market is referred to in the literature as the dual labor market. This means that, on the one hand, there is employment without fixed-term contracts, which enjoy a very high level of worker protection, and on the other hand, there is employment that is characterized by precarious, temporary employment relationships. Younger people in particular are initially employed on a temporary basis. Due to the dual labor market, there is a relatively high wage inequality in Spain. This inequality decreased between 1995 and 2002. This is due to strong real growth, which has had a more positive impact on the lower wage segments than that of the higher ones.

education

The education system is a critical factor in the face of income inequality. In Spain, on the one hand, the educational reform of 1990 (General Law of the Education System) should be mentioned, in which the school age was raised from 14 to 16 years. The number of educational qualifications has risen sharply since the middle of the 20th century, with more educational qualifications in the secondary and tertiary sectors in particular .

Another characteristic of the Spanish education system are high failure rates in university proficiency tests. As a result, there is a compressed, highly qualified upper level of education. At the same time, there is a large proportion of the population who are less well educated, which means that a large section of the population falls into a low-wage sector. This indicates a high level of income inequality. On the other hand, there is a rather low intergenerational educational persistence in Spain, so the educational level of the parents does not have a very strong impact on the educational level of the offspring. This results in a smaller effect on income inequality than in other European countries.

Public social spending

Historically speaking, the current Spanish social system has not existed as long as that of other European countries and has its origins in 1980. Although a kind of social system already existed during the last years of the dictatorship before 1980 , it was only through the transition to a democracy more expanded. In the first years of the transformation process, the socialist top government was in charge. In 2008 the Spanish state spent 13.8% of the gross domestic product on social security for the population and was thus below the EU-27 average of 17.6% of GDP.

Great Depression

education

The structural problems in the education system became apparent during the global economic crisis . As a result of the crisis, over a million people between the ages of 16 and 24 were unemployed in Spain. There was a high dropout rate among unemployed youth. In addition, it is difficult for well-trained young people to enter the labor market due to a lack of work experience.

labour market

Shortly before the economic crisis began at the end of 2007, the unemployment rate was at a historic minimum of 6% for men and 10% for women. The crisis resulted in two negative shocks on the labor market. The first in 2007 on the housing market and the second in 2008 on the financial market. The unemployment rate increased as a result of both shocks. Those people who had not previously worked in the labor market and were about to enter were hard hit by the crisis. This resulted in increased youth unemployment in Spain after the economic crisis, which was well above the EU average.

The crisis reduced the number of people employed in the construction sector, which mainly employs young people. In 2010 there were fewer male individuals between 16 and 30 employed than before the crisis. In addition, the crisis hit mainly workers in the low-wage sector, i.e. individuals who were already severely negatively affected by income inequality before the crisis. It can be concluded from this that the crisis increased inequality through changes in the labor market, as special groups were hit and had only slightly or hardly recovered after the crisis.

bibliography

- Jordi Bacaria, Josep M. Coll, Elena Sánchez-Montijano: The Labor Market in Spain: Problems, Challanges and Future Trends. social inclusion monitor, September 1, 2015, accessed on January 18, 2019

- Tomas Hellebrandt: Income Inequality Developments in the Great Recession . Ed .: SOEP - The German Socio-Economic Panel Study at DIW Berlin. 2014.

- Ana Suarez Alvarez, Ana Jesus Lopez Menendezez: Inequality of opportunity and income inequality in Spain: An analysis over time . Ed .: Society for the Study of Economic Inequality. December 2016.

- Marta Pascual Sáez, Noelia González-Prieto, David Cantarero-Prieto: Is Over-Education a Problem in Spain? Empirical Evidence Based on the EU-SILC . In: Social Indicators Research . Volume 126, No. 2, March 1, 2016, ISSN 1573-0921, pp. 617-632, doi : 10.1007 / s11205-015-0916-7.

- Josep Pijoan-Mas, Virginia Sánchez-Marcos: Spain is different: Falling trends of inequality . In: Review of Economic Dynamics (= Special issue: Cross-Sectional Facts for Macroeconomists ). Volume 13, No. 1, January 1, 2010, ISSN 1094-2025, pp. 154-178, doi : 10.1016 / j.red.2009.10.002 (sciencedirect.com [accessed January 19, 2019]).

- Sara Torregrosa-Hetland: STICKY INCOME INEQUALITY IN THE SPANISH TRANSITION (1973-1990) * . In: Revista de Historia Economica - Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History . Volume 34, No. 1, March 2016, ISSN 0212-6109, pp. 39-80, doi : 10.1017 / S0212610915000208 (cambridge.org [accessed January 19, 2019]).

- B. Mitchell, E. Haigis, B. Steinmann, R. Gitzelmann: Reversal of UDP-galactose 4-epimerase deficiency of human leukocytes in culture . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America . Volume 72, No. 12, December 1975, ISSN 0027-8424, pp. 5026-5030.

- JA McHard, JD Winefordner, JA Attaway: A new hydrolysis procedure for preparation of orange juice for trace element analysis by atomic absorption spectrometry . In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry . Volume 24, No. 1, 1976-1, ISSN 0021-8561, pp. 41-45, PMID 1435 (nih.gov [accessed January 19, 2019]).

Web links

- OECD Income Inequality: https://data.oecd.org/inequality/income-inequality.htm#indicator-chart

- Eurostat: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Ada Ferrer-i-carbonell, Xavier Ramos, Monica Oviedo: GINI Country Report: Growing Inequalities and their Impacts in Spain . Ed .: AIAS, Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labor Studies. Amsterdam April 1, 2013 ( online [PDF]).

- ↑ a b c d Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income (source: SILC) (ilc_di12). Eurostat, accessed 6 May 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e Average and median income by age and gender - EU-SILC survey (icl_di03). Eurostat, accessed 19 January 2019 .

- ↑ a b OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD). In: https://data.oecd.org/ . OECD, accessed May 6, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e f S80 / S20 income quintile ratio by gender and by age group - EU-SILC survey (icl_di11). Eurostat, accessed 6 May 2019 .

- ↑ S80 / S20 income quintile ratio by gender. Retrieved May 6, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c Income distribution by quantile - EU-SILC survey (ilc_di01). Eurostat, accessed 6 May 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d Rate of people at risk of poverty by risk of poverty line, age and gender - EU-SILC survey (ilc_li02). Eurostat, accessed 19 January 2019 .

- ↑ At- risk-of-poverty rate (EU-SILC). Destatis Federal Statistical Office, accessed on January 21, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c Regional distribution of income - EU-SILC survey (icl_di11). In: Eurostat. Eurostat, accessed 9 May 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e Metropolitan areas. In: OECD. OECD, accessed May 9, 2019 .

- ↑ a b GDP per capita in PPS. Eurostat, 1 June 2018, accessed 18 January 2019 .

- ↑ J. Ignacio García-Pérez and Fernando Muñoz-Bullón: Transitions into Permanent Employment in Spain: An Empirical Analysis for Young Workersbjir_750 103..1 . Ed .: British Journal of Industrial Relations. March 1, 2011, p. 103-143 .

- ↑ Lacuesta, A. and Izquierdo, M .: The contribution of changes in employment composition and relative returns to the evolution of wage inequality: the case of Spain . Ed .: Journal of Population Economics. S. 511-543 .

- ↑ Schuetz, G .; Origin, HW and Woessmann, L .: Education policy and equality of opportunity . Ed .: Kyklos. S. 279-308 .

- ↑ State expenditure by area of responsibility. Eurostat, 3 September 2018, accessed 18 January 2019 .

- ↑ Bacaria, J .; Coll, J .; and Sanchez-Montijano: The Labor Market in Spain: Problems, Challenges and Future Trends. Social Inclusion Monitor, September 1, 2015, accessed January 18, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Malo, MA: Labor Market Measures in Spain 2008-13: Crisis and Beyond. Ed .: International Labor Office Research Dept. 2015, ISBN 978-92-2129778-9 .