Distribution of income in Poland

The income distribution in Poland considers the distribution of income in Poland and their development at the personal and functional level. The personal income distribution considers how the income of an economy is distributed to individual persons (groups) e.g. B. is distributed in households. To measure income inequality, on the one hand, different income definitions can be used and, on the other hand, different statistical concepts can be applied.

Roughly speaking, a distinction is made between gross income, net income , taxable income and disposable income . In addition, the type and aggregation of income play a crucial role in the interpretation and comparability of indicators. The personal income distribution is measured by Eurostat on the basis of the equivalised disposable income . Basically, a distinction is made between two types of income - the income that is earned through dependent and self-employed work (market income or primary income ) and income after state redistribution (secondary income). The primary income consists of income from employment, business activity, rental and leasing, as well as investment income before taxes and duties. The consideration of social security contributions, direct taxes as well as public (e.g. social assistance, unemployment benefit) and private (e.g. maintenance) transfers is called secondary income.

The Gini index is usually used to measure income inequality . In 2017, the Gini index in Poland was 29.2 points and thus shows a rather low inequality in the distribution of income. Compared to the other countries of the European Union, the country is in the lowest (and therefore most income-equivalent) third. In comparison with the transition countries , income inequality is moderate. The median disposable income in 2017 was PLN 25,940 (around EUR 6,000), which is well below the EU-28 average. The average income was PLN 29,714.

Selected indicators

|

Average

before TP |

Average

income according to TP |

Median income

before TP |

Median income

according to TP |

Gini

before TP |

Gini

according to TP |

S80 / S20 ratio

according to TP |

Top 10% share

according to TP |

Harmonized

(2015 = 100) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 10,362 | 14,904 | 7,697 | 12,517 | 53.0 | 33.3 | 5.6 | 25.5% | 81.2 | |

| 2007 | 11,393 | 16,166 | 8,802 | 13,645 | 51.4 | 32.2 | 5.3 | 25.1% | 83.3 | |

| 2008 | 13,734 | 18,690 | 10,822 | 15,720 | 49.8 | 32.0 | 5.1 | 25.3% | 86.8 | |

| 2009 | 15,746 | 21,018 | 12,804 | 17,903 | 48.2 | 31.4 | 5.0 | 24.8% | 90.3 | |

| 2010 | 16,425 | 22,142 | 13,424 | 19,065 | 47.9 | 31.1 | 5.0 | 24.3% | 92.7 | |

| 2011 | 17,230 | 23,221 | 14,219 | 20,075 | 47.8 | 31.1 | 5.0 | 24.4% | 96.3 | |

| 2012 | 18,103 | 24,321 | 14,904 | 20,849 | 47.5 | 30.9 | 4.9 | 24.2% | 99.8 | |

| 2013 | 18.405 | 25.007 | 15.184 | 21,610 | 47.7 | 30.7 | 4.9 | 24.0% | 100.6 | |

| 2014 | 19,057 | 25,871 | 15,683 | 22,399 | 47.9 | 30.8 | 4.9 | 24.0% | 100.7 | |

| 2015 | 19,554 | 26,679 | 16,337 | 23,247 | 47.9 | 30.6 | 4.9 | 23.9% | 100.0 | |

| 2016 | 20,520 | 27,864 | 17,418 | 24,618 | 46.7 | 29.8 | 4.8 | 22.9% | 99.8 | |

| 2017 | 21,385 | 29,714 | 18,174 | 25,940 | 47.3 | 29.2 | 4.6 | 23.2% | 101.4 |

Distribution of income in general

Median and average income

While the average income is the arithmetic mean of all incomes in the population under consideration, the median income is the income of the person who is exactly in the middle of the income distribution (exactly 50% of the population earn less than this person, 50% earn more). These two measures differ in most cases, with the median proving to be more robust against outliers than the average. Since high peak incomes push the median income upwards but not the median income, the former is higher than the latter. In this context, one speaks of a right-skewed distribution.

In 2017, the median income after social transfers and pensions in Poland was PLN 29,714 (EUR 6,810) and the median income was PLN 25,940 (EUR 5,945). For the EU-28 countries , the corresponding weighted values were EUR 19,354 (average) and EUR 16,885 (median). Both nominal average and nominal median incomes in Poland have increased steadily in recent years (between 2006 and 2017 the average income after social transfers and pensions rose by 99.4% and the corresponding median by 107.2%). During the same period, the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) rose by only 24.9%, meaning that most of the income growth was real (i.e. also present after deducting the price increase).

The graph shows the course of nominal and real median and average incomes in Poland from 2005 to 2017 and their marked increase. Real income adjusts for inflation using the HICP with the base year 2015.

The effects of the economic crisis can be clearly seen in the collapse in real and nominal incomes in 2010. Due to the selection of 2015 as the base year of the HICP and a resulting nominal increase but real loss in income after the crisis, the gap between real and nominal income is closing. Given the low inflation rates between 2013 and 2016, real and nominal median and average incomes are the same.

Gini coefficient

The Gini index (or Gini coefficient) is a method of measuring inequality. It assumes values between 0 (absolute equal distribution, all people get exactly the same amount of income) and 100 (absolute unequal distribution, one person receives the entire income of the population and everyone else receives nothing). It thus indicates how far the observed population is "away" from an absolutely uniform distribution. Both for disposable income before and for income before social transfers, a steady decrease in the Gini coefficient can be observed in Poland since 2006, which means a decrease in income inequality in Poland.

If you calculate the Gini index of market income and secondary income, before and after social transfers, you can see the effects of redistribution by the state on income distribution. The Gini index of market income was 45.5 points in 2016; if you look at secondary income, it was only 28.4 points. The Gini index has fallen continuously since 2004, at that time the index was 59.4 before social transfers in 2004 and 37.6 after social transfers. Income inequality in the country has risen steadily since Poland's independence , mainly due to a greater spread of wages. On the one hand, highly qualified personnel were paid better after the opening than under the socialist regime of the Soviet Union . On the other hand, there were many workers with a low level of education whose incomes fell. In the mid-2000s this spread of wages narrowed due to emigration and an increase in the educational level of the population. These dynamics can be seen in the Gini index before social transfers. But the redistribution of the state also had an effect on the decline in the Gini index of income after social transfers and taxes. In 2007 a tax reform was implemented in Poland, which grants tax rebates for children and has made a significant contribution to reducing the previously growing inequality. This was € 306.40 per year, 6% of the nominal median income in Poland in 2017.

Both the Gini index of market income and secondary income in Poland are below the EU average. If one compares the development of the Gini index in Poland with the values of its neighboring countries, the increase in income equality becomes even clearer. While Poland still had the highest Gini index in the country group before and after social transfers in 2004, the index in 2016 was already below that of Lithuania and Germany .

S80 / S20 ratio

Another measure for measuring inequality is the S80 / S20 ratio. It describes the ratio of the total income of the top quintile ( i.e. the highest income 20%) in the income distribution to the total income of the bottom quintile (i.e. the lowest income 20%). This also shows that the unequal distribution in Poland has been decreasing over time: while the top quintile earned 5.6 times as much in 2006 as the bottom quintile, in 2017 it was only 4.6 times as much .

Income share of the top 10%

The total income of the top decile ( i.e. the 10% with the highest income) is added up and expressed as a percentage of the total income of the observed population. This number is also decreasing in Poland, it decreased from 25.5% (2006) to 23.2% (2017).

As with the Gini index before, one can see a big change in the years before the economic crisis . While the share of the richest 10 percent in Poland before 2014 was well above the EU average, in 2017 it was 0.7 percentage points lower. In comparison with Poland's neighboring countries, one can see that the decrease in the income share was very continuous but significant. In 2005 the value was similar to that in Lithuania, which has the greatest inequality here; in 2017 the proportion fell below the EU average and is now on a par with Germany.

Income distribution by sex

S80 / S20 income quintile ratio

Like the Gini coefficient , the quintile ratio S80 / S20 is also a measure used to describe the unequal distribution of income. It compares the earnings gap between the 20% of households with the highest incomes (top quintile) and the 20% of households with the lowest incomes (bottom quintile). The further this value is from 1, the more unequal the income distribution between these two groups is. Income is understood to be the equivalised disposable income . The development of the income quintile ratio of men and women in Poland is constantly parallel to the development in the EU average. The income quintile ratio for men in Poland was most recently 4.7 (EU average: 5.1) in 2017 and 4.4 (EU average: 5.1) for women. The income quintile ratio of men is 0.3 percentage points higher than that of women. The difference between the sexes has remained relatively the same over the years and is relatively far below the EU average.

Unadjusted gender pay gap

The unadjusted gender pay gap is the difference between the average gross hourly wage of women and men as a percentage of the average gross hourly wage of male employees. The gender pay gap is calculated based on the following data:

- The four-year Structure of Earnings Survey (SES) 2002, 2006, 2010 and 2014 to the extent required by the SES Regulation;

- National estimates based on national sources for the years between the SES surveys from the reference year 2007 with the same coverage as the SES.

These data are broken down into economic sectors (Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community - NACE ), economic control of the company (public / private) and working time (full-time / part-time) and age (six age groups).

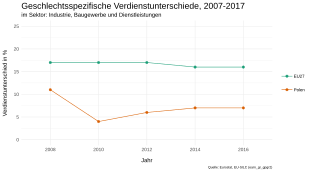

The gender wage gap is calculated to examine the wage gap between men and women . The graphic shows the development of the unadjusted gender wage gap in the NACE2 sectors of industry, construction and services (excluding public administration, defense and social insurance) in Poland compared to the EU-27 member states. In 2010, the gender pay gap in industry, construction and services in Poland was 11%. While the indicator remained constant in the EU, the gender pay gap in Poland fell below 5% by 2010. This means that the income gap between men and women has halved between 2008 and 2010 and, despite a steady increase since then to around 7% (2017), is still well below the European average: the gender wage gap in the same sector is within the European average for the year 2008 with 17.3% clearly above the Polish value and only decreased by one percentage point to 16% by 2017

Distribution of income by region

Regional income differences are more pronounced in Poland than the income differences between men and women. This spatial component becomes particularly visible when one compares the metropolitan area around Katowice (belonging to the Silesian Voivodeship ) with the Subcarpathian region. In general, the Subcarpathian Voivodeship is one of the poorest regions in the EU.

Disposable household income

The average disposable income per inhabitant in Poland in 2016 varied between 9,600 euros in the Sub-Carpathian Mountains and 13,500 euros in Silesia. The top regions also include Lodsch (EUR 13,200), Greater Poland (EUR 12,700) and Lower Silesia (12,600). Podlachie (EUR 10,200), Lublin (EUR 10,500), Świętokrzyskie (EUR 10,600) and Warmia-Masuria (EUR 10,600) are among the voivodships with the lowest disposable per capita income.

Poverty and social exclusion

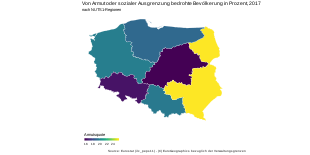

According to the Eurostat definition, a person is at risk of poverty and social exclusion if they are at risk of poverty , suffer from material deprivation or live in households with very low employment. A person with an equivalised income below 60% of the national median equivalised income is considered to be at risk of poverty. Material deprivation is defined as the involuntary inability to afford certain goods of daily life and includes on the one hand the economic burden and on the other hand the lack of durable consumer goods. The proportion of the population at risk of poverty in Poland in 2017 was between 15.5% in eastern Poland and 25.9% in central Poland. Viewed over time, the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion in Poland has steadily decreased since 2005, from 45.3% in 2005 to 19.5% in 2017, although the spatial differences have not remained constant over time .

| NUTS2 regions

+ Warsaw (German) |

NUTS2 regions

+ Warszawski (Polish) |

Available income

per capita (PPS), 2015 |

Available income

per capita (PPS), 2016 |

NUTS1 regions

German Polish) |

Of poverty or

social exclusion threatened population in percent, 2015 |

Of poverty or

social exclusion threatened population in percent, 2016 |

Of poverty or

social exclusion threatened population in percent, 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lodsch | Lódzkie | 12,100 | 13,200 | Central region

(Centralny region) |

21.2% | 18.7% | 15.5% |

| Mazovia | Mazowiecki regionalny | 10,600 | 10,700 | ||||

| Warsaw | Warszawski stoleczny | 17,400 | 17,500 | ||||

| Lesser Poland | Malopolskie | 11,300 | 11,500 | Southern region

(Poludniowny region) |

21.6% | 20.8% | 19.7% |

| Silesia | Slaskie | 13,500 | 13,500 | ||||

| Lublin | Lubelskie | 10.100 | 10,500 | Eastern region

(Vodschni region) |

27.6% | 27.7% | 25.9% |

| Subcarpathian | Podkarpackie | 9,400 | 9,600 | ||||

| Holy Cross | Swietokrzyskie | 10,400 | 10,600 | ||||

| Podlaskie | Podlaskie | 9,700 | 10,200 | ||||

| Greater Poland | Wielkopolskie | 12,400 | 12,700 | Northwest region

(Pólnocno-zachodni region) |

23.7% | 21.6% | 19.9% |

| West Pomerania | Zachodniopomorskie | 11,500 | 11,800 | ||||

| Lebus | Lubuskie | 10,700 | 10,900 | ||||

| Lower Silesia | Dolnoslaskie | 12,400 | 12,600 | Southwest region

(Region póludniowo-zachodni) |

21.0% | 22.1% | 16.0% |

| Opole | Opolskie | 10,600 | 10,900 | ||||

| Kuyavian Pomeranian | Kujawsko-Pomorskie | 10,500 | 10,900 | Northern region

(Region pólnocny) |

25.5% | 21.5% | 19.0% |

| Warmia-Masuria | Warminsko-Mazurskie | 10,200 | 10,600 | ||||

| Pomerania | Pomorskie | 11,500 | 11,700 |

backgrounds

The history of income distribution in Poland is marked by a sharp increase in inequality with the end of the People's Republic (more than in Hungary or the Czech Republic , countries that have made a similar transition to a market economy ), followed by a moderate decrease in inequality since 2007. The main reasons For the existing inequality, the relatively low progression in income taxation and the high density of atypical forms of employment are mentioned in the scientific literature . In addition, since the end of the People's Republic , people with a tertiary education have received significantly higher salaries than people with lower qualifications (to an extent that is above the EU-27 average). However, in recent years this difference has narrowed.

The high density of atypical employment relationships in Poland today is partly due to the global financial crisis , as a result of which there were legislative changes in 2009 to make labor markets and wages more flexible. In the literature, however, there is currently no consensus on the extent to which the lack of severe consequences of the crisis for the Polish economy can be attributed to precisely these measures. While on the one hand it is argued that these regulations were able to compensate for the decline in demand for companies and thereby prevent serious consequences for the Polish economy, it is unclear whether the resulting expansion of precarious forms of employment - especially for multinational sales companies - was necessary to this extent.

Existing income inequality may have an impact on the confidence of the Polish population in political institutions and the perceived association of wealth with corruption (or on how much wealth is perceived as "deserved"). In addition, a large volume of academic literature generally deals with the question of the extent to which income and wealth inequality influence or are influenced by economic growth . There is evidence that inequality can, under certain circumstances, be a hindrance to growth.

Two recently introduced measures have had a significant impact on income distribution in Poland: First, the new gross minimum wage of PLN 2,000 introduced in 2015 , which, given the large proportion of the population employed in the low-wage sector, has made a significant contribution to reducing income inequality. On the other hand, the "Rodzina 500 plus" fertility bonus was introduced in 2016, which offers needs-based monetary benefits from the first child and universal benefits from the second child. While this measure has so far proven to be effective in combating child poverty, critical voices point to the negative effects on the labor market participation of mothers. The substantial gender pay gap that already exists in Poland could become larger as a result.

bibliography

- V. Astrov, M. Holzner, S. Leitner, I. Mara, L. Podkaminer, A. Rezai: The wage development in the Central and Eastern European member states of the EU. Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, 2018. (wiiw.ac.at , accessed on May 12, 2019)

- M. Brzeziński: Is high inequality an issue in Poland? Policy Paper 1/2017. Instytut Badań Strukturalnych. (ibs.org.pl , accessed May 14, 2019)

- F. Gęstwicki, E. Wędrowska: Assessment of the Degree of the Divergence and Inequality of Household Income Distribution in Poland in the Years 2005–2013. In: Folia Oeconomica Stetinensia. Volume 16, No. 1, 2016, pp. 50-62.

- Horacio Levy, Leszek Morawski, Michal Myck: Alternative taxbenefit strategies to support children in Poland. EUROMOD Working Paper, No. EM3 / 08, University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER), Colchester 2008. (econstor.eu , accessed May 14, 2019)

- J. Muszyńska, J. Oczki, E. Wędrowska: Income Inequality in Poland and the United Kingdom. Decomposition of the Theil Index . closely. In: Folia Oeconomica Stetinensia. Volume 18, No. 1, 2018, pp. 108-122.

- S. Gomułka: Poland's economic and social transformation 1989–2014 and contemporary challenges. In: Central Bank Review. Volume 16, Issue 1, 2016, pp. 19-23.

- P. Strzelecki, R. Wyszyński: Poland's labor market adjustment in times of economic slowdown - WDN3 survey results . (= Working Paper. 233). Narodowy Bank Polski 2016.

- Adam Mrozowicki, Triin Roosalu, Tatiana Bajuk: Precarious work in the retail sector in Estonia, Poland and Slovenia: trade union responses in a time of economic crisis. In: Transfer: European Review of Labor and Research. Volume 19, No. 2, 2013, pp. 267-278.

- I. Magda: The "Family 500+" child allowance and female labor supply in Poland. (= IBS Working Paper. 01/2018). Instytut Badań Strukturalnych, 2018.

- A. Bargu, M. Morgandi: Can Mothers Afford to Work in Poland? Labor Supply Incentives of Social Benefits and Childcare Costs. (= Policy Research Working Paper. No. 8295). World Bank, Washington, DC 2018.

- Anna Ruzik, Magdalena Rokicka: The gender pay gap in informal employment in Poland. Center for Social and Economic Research, 2010.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Eurostat: Database ilc_di12. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Michał Brzeziński: Is high inequality an issue in Poland?

- ↑ Eurostat: Database ilc_di03. Retrieved January 18, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Eurostat: Database ilc_di13. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d Eurostat: Database ilc_di03. Retrieved January 18, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Eurostat: Database ilc_di12b. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Eurostat: Database ilc_di12. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Eurostat: Database ilc_d11. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Eurostat: Database ilc_di01. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Eurostat: Database prc_hicp_aind. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ HICP (2015 = 100) - annual data (average index and rate of change) - Eurostat. Retrieved May 14, 2019 .

- ^ The wage development in the Central and Eastern European member states of the EU (publication) . ( Online [accessed May 14, 2019]).

- ↑ OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD): Gini, poverty, income, Methods and Concepts - OECD. Retrieved May 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Is high inequality an issue in Poland? Retrieved May 14, 2019 (American English).

- ↑ Michal Myck, Leszek Morawski, Horacio Levy: Alternative tax-benefit strategies to support children in Poland . EM3 / 08. EUROMOD Working Paper, 2008 ( online [accessed May 14, 2019]).

- ↑ Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey - Eurostat. Retrieved May 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income before social transfers (pensions included in social transfers) - Eurostat. Retrieved May 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Distribution of income by quantiles - EU-SILC survey - Eurostat. Retrieved May 14, 2019 .

- ↑ S80 / S20 income quintile share ratio by sex and selected age group - EU-SILC survey - Eurostat. Retrieved May 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Gender pay gap in unadjusted form by NACE Rev. 2 activity - structure of earnings survey methodology - Eurostat. Retrieved May 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Glossary: Rate of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion (AROPE) - Statistics Explained. Retrieved May 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Glossary: At-risk-of-poverty rate - Statistics Explained. Retrieved May 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Eurostat data set: tgs00026

- ↑ a b Disposable income of private households by NUTS 2 regions - Eurostat. Retrieved May 19, 2019 .

- ↑ See NUTS: PL .

- ↑ a b c Eurostat - Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table. Retrieved May 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e Michał Brzeziński: Is high inequality an issue in Poland?

- ↑ Filip Edmund Gęstwicki, Ewa Wędrowska: Assessment of the Degree of the Divergence and Inequality of Household Income Distribution in Poland in the Years 2005-2013 . In: Folia Oeconomica Stetinensia . tape 16 , no. 1 , December 1, 2016, ISSN 1898-0198 , p. 50–62 , doi : 10.1515 / foli-2016-0004 ( online [accessed January 19, 2019]).

- ↑ Wędrowska Ewa, Oczki Jarosław, Muszyńska Joanna: Income Inequality in Poland and the United Kingdom. Decomposition of the Theil Index . In: Folia Oeconomica Stetinensia . tape 18 , no. 1 , June 1, 2018, ISSN 1898-0198 , p. 108–122 ( online [accessed January 19, 2019]).

- ^ Poland: Individual - Taxes on personal income. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Poland's labor market adjustment in times of economic slowdown - WDN3 survey results. (PDF) Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ^ Anti-Crisis Regulations of Polish Labor Law. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Adam Mrozowicki, Triin Roosalu, Tatjana Bajuk Senčar: Precarious work in the retail sector in Estonia, Poland and Slovenia: trade union responses in a time of economic crisis . April 30, 2013.

- ↑ Natalia Letki, Michał Brzeziński, Barbara Jancewicz: The rise of inequalities in Poland and their impacts: When politicians don't care butcitizens do .

- ↑ OECD (2014), "Focus on Inequality and Growth - December 2014".

- ↑ a b Iga Magda, Aneta Kiełczewska, Nicola Brandt: The "Family 500+" child allowance and female labor supply in Poland .

- ↑ Can Mothers Afford to Work in Poland: Labor Supply Incentives of Social Benefits and Childcare Costs. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Anna Ruzik, Magdalena Rokicka: The Gender Pay Gap in Informal Employment in Poland . No. 406 . CASE Center for Social and Economic Research, 2010 ( online [accessed January 19, 2019]).