Distribution of income in France

The income distribution in France considers the personal distribution of income in France . When analyzing the distribution of income, a distinction is generally made between the functional and the personal income distribution discussed here. Personal income distribution looks at how the income of an economy is distributed among individuals or groups (e.g. private households ), regardless of the source of income from which it originates. The personnel distribution is mostly measured by Eurostat on the basis of the equivalised disposable income . In 2017, the Gini coefficient in France was 0.293, which is 14th compared to the remaining 27 member states of the European Union.

Distribution of income in general

Concept of income

When interpreting statistical data on income, it is important to note which income term ( gross income , disposable income , income, etc.) is used. The equivalised disposable income must be distinguished from other income concepts. It is understood to mean the monetary income that is available to individual household members including transfers and minus taxes and duties. In the course of the calculation, the income of a household is first added up and then divided among the weighted number of household members. This weighting is based on an equivalence scale.

The reason for using an equivalence scale is as follows: the needs of a household increase with the number of people, but economies of scale also arise (so-called returns to scale ). For example, a two-person household usually does not need two washing machines and children consume less food than adults. In order to take account of the household composition, all incomes at the individual and household level are added up and then converted into an equivalent household income (or equivalised income for short) using an equivalence scale. Eurostat uses the modified OECD scale, which is calculated as follows: the first adult (14 years of age or older) receives a weight of one, each additional adult a weight of 0.5 and each person under 14 years of age receives a weight assigned by 0.3. The household income is then divided by the sum of the weights. A household made up of two adults and three children (one older than 14, two younger than 14) receives an equivalence factor of 2.6. This means that this household needs three times the income of a one-person household in order to be able to satisfy its needs as well as this one. Equivalence scales thus serve to make different households comparable.

Equivalised disposable income is a widely used concept because it reflects the income that must be spent on meeting individual needs. Unless otherwise specified in this article, the term income always refers to the equivalised disposable income.

Median and average income

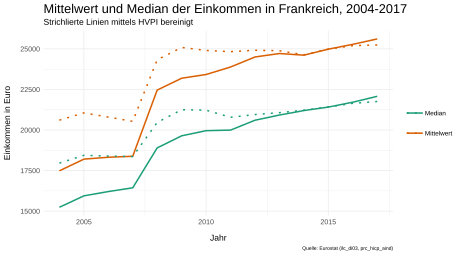

The values for average income and median income are only reported by Eurostat on the basis of nominal income . When looking over time, however, one has to consider inflation , which leads to higher prices of goods and services and consequently to weaker purchasing power . Therefore, in addition to nominal income, real income is shown here, adjusted for inflation using the harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP).

In 2017 which amounted median of nominal income € 22,077, the average € 25,613. From 2008 to 2017, both the median and the average real income increased significantly. The real median income rose from around € 20,467 to € 21,757 from 2008 to 2017; the real average income from € 24,352 to € 25,242. It is noticeable that the average of the equivalised disposable income is well above the median income over the entire period, but the difference between median and median income has remained constant over time. This means that the income distribution is skewed to the right . Such right skew is a typical characteristic that can be observed in the distribution of wealth or income of a population. A right skewed distribution results when the difference between the incomes of people with low and middle income is smaller than the difference between people with middle and high income.

| year | Average, nominal | Median, nominal | HICP | Average, real with base year 2015 | Median, real with base year 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 22,462 | 18,899 | 92.34 | 24,325 | 20,467 |

| 2009 | 23,191 | 19,644 | 92.44 | 25,088 | 21,251 |

| 2010 | 23,421 | 19,960 | 94.05 | 24,903 | 21,223 |

| 2011 | 23,882 | 19,995 | 96.20 | 24,825 | 20,785 |

| 2012 | 24,499 | 20,603 | 98.33 | 24,915 | 20,953 |

| 2013 | 24,713 | 20,924 | 99.31 | 24,885 | 21,069 |

| 2014 | 24,612 | 21.199 | 99.91 | 24,634 | 21,218 |

| 2015 | 24,982 | 21,415 | 100.00 | 24,982 | 21,415 |

| 2016 | 25,278 | 21,713 | 100.31 | 25,200 | 21,646 |

| 2017 | 25,613 | 22,077 | 101.47 | 25,242 | 21,757 |

- ↑ a b To obtain real income, nominal income is adjusted for inflation using the harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP): real income = nominal income / HICP * 100

Gini coefficient

The Gini coefficient is the most frequently used indicator to depict inequalities . It expresses how far the income distribution of a country deviates from a perfectly equal distribution.

Basically, it can assume values between 0 and 1, with 0 representing a completely equal distribution; 1 a completely unequal distribution. A disadvantage of the Gini coefficient is that it reacts much more strongly to changes in the middle of the distribution than to changes at the edges of the distribution.

In France, the Gini coefficient has remained relatively constant over the observation period from 2004-2016 and is on average a little below the value of 0.3. During the global financial crisis from 2008 to 2011, there was a relatively sharp increase in the Gini coefficient and thus income inequality. In the course of the following years, however, the Gini coefficient in France fell again. In addition to the common Gini index for income after taxes and transfers, the graphic also shows the Gini index for pure market income as gross income . In these statistics, too, there was a not insignificant increase during the global economic crisis. Overall, it is noticeable how much the value of the Gini coefficient for market income is above the value for disposable income. This discrepancy shows the extent and the success with which the state redistributes the incomes of its citizens in the interest of a more equitable distribution and social stability. In 2017, the Gini coefficient was below the weighted average of the European Union of 0.307. Compared to the Gini coefficients of the remaining EU member states, France was in 14th place in 2017 and thus in the middle of the field.

S80 / S20 quintile ratio

The S80 / S20 quintile ratio indicates the factor by which one has to multiply the income of the poorest 20 percent of the population in order to obtain the income of the richest 20 percent. In contrast to the Gini coefficient, the focus of this indicator is on the two outer edges of the income distribution.

Like the Gini coefficient, the S80 / S20 quintile ratio rose in the course of the global economic crisis: In 2008 the figure was 4.4; in 2011 it reached the highest value of the examined period with 4.6. By 2017, however, the quintile ratio had fallen back to a value of 4.4. Overall, this key figure remained relatively constant in the observed period. The number can be interpreted in the sense that in 2017 the richest 20 percent had more than four times as much income as the poorest 20 percent. Based on this measure, too, France's income inequality is below the weighted EU average, which is 5.1.

In the attached graphic, the S80 / S20 quintile ratio is broken down according to the sexes. It can be seen that in these statistics there are no or hardly any differences between men and women and that both curves follow the same course over time.

Top 10% share

This measure expresses the proportion of total income that goes to the highest-earning 10 percent of the total population. From 2008 to 2011 this value increased from 25.2% to 25.9%. It then fell again, in 2017 it was 24.5%. This means that in 2017 the 10 percent of the French population with the highest incomes had 24.5 percent of total income. In the same year, the weighted EU average of the top 10% share was 23.9%.

The extensive data set in the World Inequality Database also enables conclusions to be drawn about the top incomes in France . See World Inequality Report . Economists working with Thomas Piketty analyzed the development of top incomes in the period from 1900 to 2014. In contrast to Eurostat, however, they did not use disposable income , but income before taxes and transfers . In addition, they do not use an equivalence scale , but assume that each household member keeps their individually earned income for themselves. According to this, the share of the richest 10 percent of total income has risen sharply since the 1980s. From 2008 to 2013 the share of the top 10% fell slightly, but in 2014 it remained at a higher level than at the beginning of the 1980s. The top 5% share increased significantly from 1983 to 2014. This is not only due to increases in capital income , but also to an increase in labor income . The top 1% share recorded the greatest gain: between 1983 and 2007 it rose from around 8% to more than 12%, which corresponds to an increase of more than 50%. One of the reasons given for this development is the decreasing influence of trade unions . The increase in asset concentration may also have contributed to this.

At-risk-of-poverty rate

The development of poverty can be understood as a sub-area of income distribution: While the former relates to the entire extent of the distribution, poverty indicators are limited to the lowest part of the income distribution.

The at- risk-of-poverty rate expresses what proportion of the population is at risk of poverty and social exclusion due to their relatively low income. A person is at risk of poverty if the equivalised income of their household is less than 60% of the median income of the total population. The indicator therefore does not take into account any income in kind that is typically obtained from the use of public services. (e.g. through free childcare or visits to the doctor). The at-risk-of-poverty rate also depends directly on a country's median income. Therefore it often, but not necessarily, indicates a low standard of living.

At-risk-of-poverty is always determined at household level. This means that either all members of a household are considered to be at risk of poverty or none. A person who has no income is therefore not necessarily at risk of poverty. This is because when determining the at-risk-of-poverty rate, by using the equivalised income, it is assumed that all members of a household share their entire income equally.

In 2017, 13.3% of the population in France was considered to be at risk of poverty. This puts France well below the EU average of 16.9. It is striking that the rate increased by 1.6 percentage points between 2008 and 2012. In 2012, the at-risk-of-poverty rate reached 14.1%, the highest level since 2001. This significant increase is likely to be related to the global financial crisis , which contributed to declining economic growth in France.

A household's likelihood of being at risk of poverty depends on certain characteristics of the household. For example, in France women are significantly more likely to live in households at risk of poverty than men. Single women in particular are exposed to a higher risk of poverty. This has to do with the fact that women earn less on average. In addition, in the event of separation, women take on childcare significantly more often than men, which often means a time and financial burden.

In 2008, for example, 13.3% of the female population in France were considered to be at risk of poverty compared with 11.7% of the male population. The at-risk-of-poverty rate by gender also increased the most between 2008 and 2012, so that in 2012 14.6% of women and 13.6% of men were classified as at risk of poverty. In 2017, 13.6% of women and 12.9% of men were considered to be at risk of poverty. Over the entire period, it has been shown that women are on average more at risk of poverty.

Gender income inequality

The attached graph shows the development of the gender wage gap , i.e. the difference in average incomes between women and men, in France over the period 2007–2017.

It can be seen that the wage gap decreased, especially at the beginning of the observation period, but has remained constant in recent years. Nevertheless, a decrease in the income gap between women and men can be observed both in France and throughout the EU.

The values used in the graph show the gross hourly wage and are not adjusted. Therefore, no adjustments were made for differences in various income-related factors for which there are statistical differences between women and men. These factors include, among other things, the level of training or the sector in which an employee works. When considering the gender-wage gap, such differences are usually taken into account with the help of econometric methods. In this case one speaks of an adjusted gender balance gap.

Regional inequality

In the attached graphic, the average incomes of the individual regions can be clearly seen. The country was divided up using the so-called NUTS system . This division takes place at different levels and divides a country into smaller and smaller sections. NUTS level 2 was used for the graphic.

Compared to other European countries such as Germany or Italy , income in France is relatively evenly distributed across the different regions of the country.

The highest average income is achieved in the Île-de-France region , which mainly includes the capital Paris . In contrast, the Nord-Pas de Calais , Languedoc-Roussillon and Corsica regions have the lowest average incomes in a national comparison.

backgrounds

The development of income distribution can be traced back to various factors, such as macroeconomic, political, demographic and institutional changes. In the case of France, for example, the global economic crisis had a significant impact on the distribution of income. An increased proportion of single parents in the total population and the aging of the population are also likely to have affected income inequality.

In the wake of the global economic crisis, France fell into recession after a period of sustained economic growth . In 2009, real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was 4.2% below the pre-crisis high of 2007. Compared to neighboring countries (Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Great Britain) this suggests that the French economy is only doing moderate damage took. However, it took a comparatively long time for the French economy to recover from this recession.

The French government reacted to this by increasing government spending (e.g. to finance infrastructure projects) and cutting taxes. In 2009, government spending was 1.6% higher than in the previous year. Taxes were then increased to finance higher government spending. In 2012, for example, the existing five income tax brackets were expanded to include a sixth rate. The marginal tax rate for annual incomes in excess of € 150,000 has been raised from 40% to 45%; In addition, a top tax rate of 75% was decided for annual incomes of one million or more. The latter was only in force in 2013 and 2014.

The global economic crisis also affected the French labor market . From 2007 to 2012, earned income rose by an average of around 0.2% per year, while before the crisis, from 2002 to 2007, it grew by 0.6% per year. In the period from 2007 to 2014, the employment rate of 16 to 74 year olds fell by 1.2%; that of 16 to 29 year olds fell by 3.5%. It is noticeable that the employment rate among the older population continued to rise during and after the recession. A pension reform may have contributed to this development: In 2010 the retirement age was raised from 60 to 62 years. In addition, labor law made it difficult to lower wages. Instead, employers increasingly responded to the recession by stopping admission and not renewing fixed-term contracts. As a result, job seekers have found it difficult to access the labor market. Since job seekers are on average younger than employees, these factors increase income inequality between age groups.

bibliography

- Antoine Bozio et al .: European Public Finances and the Great Recession: France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom Compared . Ed .: Fiscal Studies. 4th edition. No. 36. Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2015, pp. 405–30.

- Nicolas Frémeaux, Thomas Piketty : France: How Taxation Can Increase Inequality. In: Brian Nolan et al (eds.): Changing inequalities and societal impacts in rich countries. Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 248-270.

- Bertrand Garbinti, Jonathan Goupille-Lebret, Thomas Piketty: Income Inequality in France, 1900-2014: Evidence from Distributional National Accounts (DiNA). Ed .: Journal of Public Economics. No. 162. Elsevier, 2018, 63-77.

- Joseph Gastwirth: Is the Gini Index of Inequality Overly Sensitive to Changes in the Middle of the Income Distribution? Ed .: Statistics and Public Policy. 4th edition. No. 1. American Statistical Association, 2017, pp. 1-11.

- Elena Karagiannaki: The Empirical Relationship Between Income Poverty and Income Inequality in Rich and Middle Income Countries . Ed .: London School of Economics. 2017.

- Thomas Piketty , Emmanuel Saez , Stefanie Stantcheva: Optimal Taxation of Top Labor Incomes: A Tale of Three Elasticities . Ed .: American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 6th edition. No. 1. American Economic Association, 2014, pp. 230-71.

Web links

- https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database Homepage of the statistical office of the EU (Eurostat)

- http://www.oecd.org/france/ Key figures and indicators of the OECD on the economic and social situation in France

- https://wid.world/ Key figures and indicators of the World Inequality Database on the distribution of income and wealth (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Definition: personal income distribution. Retrieved August 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Eurostat: Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income Source: SILC. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Eurostat: Glossary: Equivalent disposable income. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Eurostat: Mean and median income by household type - EU-SILC survey. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Eurostat Database: Mean and median income by household type - EU-SILC survey. Retrieved January 18, 2019 .

- ↑ Eurostat Database: Mean and median income by household type - EU-SILC survey. Retrieved January 18, 2019 .

- ↑ Eurostat Database: HICP (2015 = 100) - Annual data (average index and rate of change). Retrieved January 18, 2019 .

- ^ A b Joseph Gastwirth: Is the Gini Index of Inequality Overly Sensitive to Changes in the Middle of the Income Distribution? Ed .: Statistics and Public Policy. 4th edition. No. 1 . American Statistical Association, 2017, pp. 1-11 .

- ^ OECD: Income inequality. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Eurostat: Glossary: Income quintile share ratio. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Eurostat: S80 / S20 income quintile ratio by gender and by age group - EU-SILC survey. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Eurostat: S80 / S20 income quintile ratio. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Eurostat: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Bertrand Garbintia, Jonathan Goupille-Lebretb, Thomas Piketty: Income inequality in France, 1900–2014: Evidence from Distributional National Accounts (DINA) . Ed .: Journal of Public Economics. No. 162 . Elsevier, 2018, p. 63-77 .

- ↑ Elena Karagiannaki: The Empirical Relationship Between Income Poverty and Income Inequality in Rich and Middle Income Countries . Ed .: London School of Economics. 2017.

- ↑ Eurostat: Glossary: At-risk-of-poverty rate. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Eurostat: EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) methodology - concepts and contents. Eurostat, accessed on February 28, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Eurostat: At-risk-of-poverty rate by poverty threshold, age and sex - EU-SILC survey. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ^ Anne Brunner et al .: Rapport sur la pauvreté en France . Ed .: Observatoire des Inegalités. Paris 2018.

- ↑ Davide Barbieri et al .: Poverty, gender and intersecting inequalities in the EU . Ed .: European Institute for Gender Equality. Vilnius, Lithuania 2013.

- ↑ Eurostat: unadjusted-pay-gap.

- ↑ Eurostat: Income distribution by NUTS-2 regions.

- ^ Nicolas Frémeaux, Thomas Piketty: France: How Taxation Can Increase Inequality . In: Brian Nolan et al (Eds.): Changing Inequalities and societal impacts in rich countries . Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 248-270 .

- ↑ a b c Antoine Bozio et al .: European Public Finances and the Great Recession: France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom Compared . Ed .: Fiscal Studies. 4th edition. No. 36 . Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2015, p. 405-30 .

- ^ Mathias André, Antoine Bozi, Malka Guillot, Louise Paul-Delvau: French Public Finances through the Financial Crisis: It's a Long Way to Recovery . In: Institute for Fiscal Studies (Ed.): Fiscal Studies . tape 36 , p. 431-452 .

- ↑ a b Christel Aliaga et al .: France, portrait social. Edition 2014 . Ed .: Insee. Paris 2014.