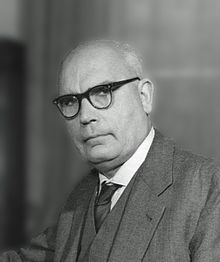

Emil Rupp

Emil Rupp , actually Philipp Heinrich Emil Rupp , (* July 1, 1898 in rows (now part of Sinsheim ), † April 10, 1979 in Leipzig ) was one of the most famous German physicists between 1926 and 1935 , but his alleged experiments and publications later were recognized as completely falsified. In a second professional orientation he became a recognized specialist in the field of graphic technology .

Career

Emil Rupp studied physics in Göttingen and Heidelberg , where he was a student of Philipp Lenard , from whom he received his doctorate summa cum laude in 1920 . Despite his brilliant qualifications, he initially found “only” a job as an industrial physicist at AEG in Berlin . There he continued to work intensively to achieve a habilitation and ultimately a professorship through sensational work (including in the titles).

Manipulated works

Albert Einstein became aware of Rupp in 1926 after his habilitation thesis Interference Investigations on Canal Rays had been published in the journal Annalen der Physik (Volume 79). Rupp's experiments clearly seemed to accommodate Einstein's theoretical concept of wave-particle dualism in photons . At the limit of what was experimentally possible at the time, Rupp also suggested with his experiments that clear evidence for the new quantum mechanical questions was already available. Although other physicists could not understand Rupp's experiments and in some cases already questioned his seriousness and although Einstein occasionally had doubts, Rupp succeeded time and again in further publishing in well-known publications and thus maintaining his very good reputation. Extensive repetitions of his experiments, which were initiated by Wilhelm Wien from the University of Munich, were unsuccessful.

Detection of counterfeits

From 1932, Rupp published “sensational” experiments on the positron , which had only been discovered shortly before. However, some of his colleagues at AEG soon realized that Rupp could not have had such high energies available as would have been necessary for such experiments, and that it must therefore be scientific falsifications . After an internal investigation by the AEG, Rupp then lost his job in 1935.

In 1935 Walther Gerlach and Eduard Rüchardt published an article in the Annalen der Physik in which they exposed Rupp's electron diffraction experiments as falsifications. After Rupp repeatedly raised critical objections e.g. B. countered with new X-ray diffraction photos, it was finally noticed that Einstein misused a sign in his publication that Rupp had "confirmed" in his experiments. Now Rupp presented a psychological report prepared by Victor-Emil von Gebsattel , in which it was confirmed that Rupp had had "dream-like states" since 1932 and that his publications since 1932 were therefore only fictitious. He published a corresponding note with statements from this report - a unique case in the history of physics - in the Zeitschrift für Physik . This was supposed to obscure the fact that his 1926 post-doctoral thesis consistently used fake experiments.

In an interview on February 18, 1963, the physicist Walther Gerlach said to Thomas S. Kuhn : “In the late twenties and early thirties, Rupp was regarded as the most important and most competent experimental physicist of all. He did incredible things. […] However, it later became clear that everything he had ever published, everything, was fake. That went on for ten years, ten years! "(Quoted from Van Dongen, translated from English.)

Aftermath

Although Rupp's case is one of the greatest scientific falsifications of the 20th century, his name soon disappeared from the minds of physicists, who hardly mentioned him anymore, so that for a long time he was hardly noticed by science historians.

English writer and physicist CP Snow used details of the fraud case for his 1960 novel about a fictional science fraud at Cambridge University ( The Affair ).

The second professional life

After his dismissal from AEG in 1935, he tried in vain to find work there with the help of his wife who emigrated to Great Britain in the same year. With the support of August Karolus , who was born in the same place as Rupp and was five years his senior , and the Leipzig physicist and later publisher Otto Mittelstädt, Rupp was able to take up a position as editor at the Bibliographical Institute in Leipzig. As an editor he also appears for the first time in a Leipzig address book from 1940.

After the Bibliographical Institute was expropriated in 1946 and transferred to a state-owned company , the manufacturing area was spun off in 1948. As part of the restructuring of the graphic industry in the GDR, an institute for graphic technology in Leipzig was founded, to which Rupp apparently switched. Because he made it to the director of this facility. On its 65th birthday, the New Germany reports on a letter of congratulations from the Central Committee of the SED :

“Today Prof. Emil Rupp, Director of the Institute for Graphic Technology Leipzig, celebrates his 65th birthday. The Central Committee congratulates the jubilee, who has made an outstanding contribution to the development of our printing industry with his work. Prof. Rupp's pioneering scientific work in the most varied areas of graphic technology contributed to the fact that his institute gained international reputation in the graphic arts world. ... "

The title without “comrade” shows that Rupp was not a member of the SED.

Rupp published several monographs in the field of graphic technology and, in addition to his activities in Leipzig, was a professor at the Technical University of Karl-Marx-Stadt .

family

Emil Rupp's first marriage was to the physicist Henriette Grünhut from Prague . As a Jew , she emigrated to Great Britain in 1935 . After unsuccessful attempts to find work for Rupp in Great Britain, they got divorced after Rupp visited Great Britain for the last time in 1939. Henriette married Owen Willans Richardson, a Nobel laureate in physics, in 1948 .

Emil Rupp met the secretary Brigitte Apreck in Leipzig. They married in 1943. The couple had children Elisabeth and Christoph, who later became pastors and mathematicians.

Emil Rupp died in Leipzig on April 10, 1979 at the age of 80 as a professor emeritus .

Fonts (selection)

- Interference studies on canal beams . Leipzig: JA Barth, (1926)

- Chemistry and physics of planographic printing . Leipzig: Bibliographical Inst., 1945

- The adhesives for bookbinding and paper processing . Halle (Saale): Knapp, 1951

- Contributions to the printability of paper and foils . Leipzig: Institute f. graphic technique, 1959

- The color transfer in single and multi-color letterpress . Leipzig: Institute f. graphic technique, 1963

- Ink transfer and drying in gravure printing . Leipzig: Inst. F. Count. Technology, 1966

literature

- Skinner, HWB and Rupp, E .: Comment on the experiment by Mr. Rupp regarding a connection between electron scattering maxima and the emission of soft X-rays , Naturwissenschaften 18 (1930), 1097-1098.

- French, AP: The strange case of Emil Rupp. In: Physics in Perspective. Volume 1, Issue 1, pp. 3-21 (1999), bibcode : 1999PhP ..... 1 .... 3F

- van Dongen, Jeroen: Emil Rupp, Albert Einstein and the Canal Ray Experiments on Wave-Particle Duality: Scientific Fraud and Theoretical Bias (PDF; 1.1 MB) , Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences 37 Suppl. (2007), 73-120.

- van Dongen, Jeroen: The interpretation of the Einstein-Rupp experiments and their influence on the history of quantum mechanics , Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences, 37 Suppl. (2007), 121-131. arxiv : 0709.3226

- Snow, CP : The Affair , Scribner, 1960, ISBN 0-684-15317-3 ; German edition: The Affair , Dt. Verl.-Anst., 1963.

- Fölsing, A .: Der Mogelfaktor , Rasch and Röhring, 1984, ISBN 3-89136-007-X

- Mario Beck: Researchers on the wrong track . Leipziger Volkszeitung , No. 60, 11./12. March 2017, p. 19 (online)

Web links

- A letter from Sommerfeld to Rupp dated January 30, 1930, in which he expresses his doubts about his electron diffraction experiments

- Armin Himmelrath: The false mirror in the contemporary history portal one day , March 9, 2008

Individual evidence

- ^ Address book of the Reichsmesse city Leipzig 1940. Retrieved on March 11, 2017 .

- ↑ Congratulations from the Central Committee. In: Archive New Germany, issue of July 1, 1963 (page 8 of the file). Retrieved March 11, 2017 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rupp, Emil |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Rupp, Philipp Heinrich Emil |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German physicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 1, 1898 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Rows , now part of Sinsheim |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 10, 1979 |

| Place of death | Leipzig |