Falange

The Falange ([ fa'laŋxe ], from ancient Greek ἡ φάλαγξ hé phálanx "tree trunk", "roller", "roll", "battle line") was a fascist movement in Spain that existed from 1933 to 1937. Its members were known as Falangists .

While they could not win a single mandate in parliamentary elections during the Second Spanish Republic (1931-1936), the movement rose to a politically and militarily important force within a few months after the beginning of the Spanish Civil War and gained a mass base. On April 19, 1937, the fascist Falangists were united with the monarchist Carlist by General Franco to form the state party FET y de las JONS , of which Franco became party leader.

Second republic

Falange Española

The Falange Española was officially founded on October 29, 1933 at the Teatro de la Comedia in Madrid . It was chaired by a group of three made up of the lawyer José Antonio Primo de Rivera , the pilot Julio Ruiz de Alda and the writer Alfonso García Valdecasas . The party name "Falange" is probably borrowed from the writings of the publicist Ernesto Giménez Caballero , who is considered to be the first fascist author in Spain, and refers to the ancient Greek battle formation of the phalanx . Despite its rather vague program, the Falange was able to gain around 2000 members by the end of the year, mainly disappointed supporters of the traditional right-wing parties and students who came to the party through the Sindicato Universitario Español (SEU) student group founded in November 1933 .

The establishment of the Falange was supported by radicalized monarchists from the Acción Española - including Pedro Sainz Rodríguez , who was involved in drawing up the party program. From the Renovación Española , the partisan arm of the Acción Española , the Falange received monthly subsidies on the basis of a personal agreement between Primo de Rivera and monarchist politicians. Since 1935 the party also received money from fascist Italy. In the long-term strategy of Acción Española aimed at the elimination of the republic, the Falange was intended to play the role of "cannon fodder" in the violent confrontation with the left and the destabilization of the republic, with the person of Primo de Riveras - large landowners, aristocrats and Son of the ex-dictator - the guarantee that Spanish fascism would not escape the control of the establishment.

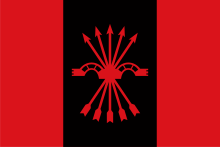

Falange Española de las JONS

In 1934 the party merged with the ideologically related, but more on political style of Nazi -oriented Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (dt .: associations Nationalsyndikalistischen offensive JONS) for Falange Española de las JONS . The leader of the JONS was Ramiro Ledesma , the founder of the Spanish national syndicalism . The new party took over from the JONS the symbol of the yoke and arrows, which can be traced back to the Reyes Católicos , as well as the black and red flag, which the JONS in turn disregarded the anarchists. The party anthem was the song Cara al Sol (German: "Face to the Sun"), composed by José Antonio Primo de Rivera .

In 1935 the new party adopted a national-social program, but tactical-ideological differences soon became clear: While José Antonio Primo de Rivera advocated the implementation of a “national syndicalist revolution” by a small group, Ramiro Ledesma wanted to turn the Falange into a mass party. This debate, which concealed a dispute within the party leadership about a more independent role for the Falange from the other right-wing parties, had little practical relevance. Until 1936 the party recruited its members almost exclusively from students and the bourgeois youth in the cities. "Led by señoritos [young men of aristocratic or upper -class origins] and mostly supported by the sons of the rich", their following remained negligible among the dispossessed mass of the population. In the parliamentary elections in February 1936, the Falange received only around 45,000 votes. After that, however, rapid growth began. In the spring of 1936, at least 15,000 members of the CEDA youth organization joined the Falange.

With reference to the control of the party by members of the traditional establishment and the social exclusivity of the members in parts of the older literature, the view that the Falange was not a “real” fascist party can hardly be found in scientific literature today. The reverse thesis, which goes back to Juan Linz and Stanley G. Payne , that the Falange from 1933 to 1937 was the only genuinely fascist party in Spain, is relativized by more recent research such as that of Ismael Saz Campos , which examines the interrelationships between the various currents examine the Spanish right in the context of a broader concept of "fascistization".

After the success of the Popular Front in the 1936 elections, violent clashes between supporters of the Falange and the left parties in Madrid and other major cities escalated dramatically. Between March and July 1936 “action groups” of the Falange unleashed a systematically escalated terror campaign against trade unionists, left-wing and liberal politicians as well as judges and police officers who were loyal to the republic; the party was so instrumental in creating the chaotic political climate that served as a pretext for the military coup, which Primo de Rivera was fully informed about: “The Falange's role was to carry out acts of terrorism in order to provoke left-wing reprisals which, taken together, would then legitimize the right-wing jeremiads about the disorder. ”Although the government had Primo de Rivera and other leading Falangists arrested on March 14, 1936 for illegal possession of weapons and banned the party, it did not prevent the party from now im The underground party continued to lead from their cells. In the first few months of the civil war, however, the entire Falange leadership group was killed or executed. José Antonio Primo de Rivera was sentenced to death in Alicante and shot on November 20, 1936 (known as "20-N" in the jargon of Spanish right-wing extremists since Franco's death on the same day in 1975).

Spanish civil war and transformation into the Movimiento Nacional

In the Spanish Civil War , the Falangist militias fought on the nationalist side under General Francisco Franco . Primo de Rivera, who was still imprisoned in Alicante , was executed by Republicans on November 20, 1936 and was quickly proclaimed a martyr of the nationalist side. The position struggles for his successor Franco decided by a decree of April 19, 1937, which instructed the union of Falange and JONS with the Carlist Comunión Tradicionalista to Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS . This largely rejected the “revolutionary” program of the Falange and paved the way for the Falange to become the state party of Franquism. Franco declared himself the leader of the "movement" ( movimiento ), as the party was now generally known. In 1943 the Falange militia was disbanded. In 1970 the FET y de las JONS were also officially renamed Movimiento Nacional. Until the end of the Franco dictatorship, it remained the only legal party in Spain.

Currents and successors

Many of the old Falangists ( camisas viejas ) reacted negatively to the increasing appropriation and disempowerment of the Falange by the state and propagated the implementation of the so-called revolución pendiente (the “outstanding revolution”), a fascist-national syndicalist reorganization of Spanish society, which Francoism largely one Had given rejection. They thus formed a kind of “right-wing opposition” to the Franco regime. The best-known representative of this political direction was Blas Piñar . One of these radical groups was the Syndicalist Student Front ( Frente de Estudiantes Sindicalistas , FES), founded in 1963, to which the later chairman of the Partido Popular (PP) and Spanish Prime Minister José María Aznar also belonged in an important role in the 1970s .

During the democratization and dissolution of the Movimiento Nacional under the interim Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez , several splinter parties formed in the right-wing extremist spectrum, three of which took part in the first free elections on June 15, 1977, but none of them entered parliament. Even today there are several groups and parties with the name “Falange” that belong to the right-wing extremist spectrum.

literature

- Kubilay Yado Arin: Franco's 'New State': from fascist dictatorship to parliamentary monarchy . Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86573-682-6 .

- Bernd Nellessen: The forbidden revolution. The rise and fall of the Falange. (= Hamburg contributions to contemporary history. Volume 1.) Leibniz-Verlag, Hamburg 1963.

- Stanley G. Payne : Fascism in Spain 1923-1977 , The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin 1999.

Web links

- Literature on the catchword Falange in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ^ Wippermann: European fascism in comparison. P. 118f.

- ↑ See Preston, Paul, The Spanish Civil War. Reaction, Revolution and Revenge, London 2016 (updated and expanded new edition, first London 1986), pp. 45, 70. In the same sense, also Blinkhorn, Martin, Conservatism, traditionalism and fascism in Spain, 1898–1937, in: derselbe (ed .), Fascists and Conservatives. The Radical Right and the Establishment in Twentieth-Century Europe, London 1990, pp. 118-137, pp. 129ff.

- ↑ Blinkhorn, Conservatism, traditionalism and fascism, p. 130.

- ^ Paul Preston , The Spanish Holocaust. Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain, London 2012, p. 118.