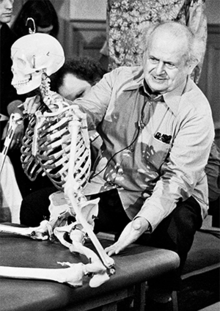

Moshe Feldenkrais

Moshé Feldenkrais (born May 6, 1904 in Slavuta , Russian Empire ; died July 1, 1984 in Tel Aviv , Israel ) was an Israeli scientist and judo teacher . He developed the Feldenkrais method of physical activity and relaxation named after him .

Life

Feldenkrais grew up in a Jewish family in Belarus Baranovichi on. He received his schooling and upbringing in traditional Jewish fashion in the cheder . At the age of fourteen he emigrated to Palestine in 1919 . There he first worked in road construction, on construction sites in Tel Aviv and as a private teacher for children. In 1927 he passed his Abitur at the Herzliya High School in Tel Aviv and went to Paris in 1930 to study electrical engineering and mechanics at the ESTP ( École Spéciale des Travaux Publics, du bâtiment et de l'industrie ), a private institute. He completed this degree. He was then a first-year student of a new course at the Sorbonne University , which could be completed with the title of Docteur Ingénieur. There is no reliable information about the course of studies during the Second World War . From 1933 until his emigration to England in 1940, Feldenkrais worked as an engineer in the research laboratory of Irene Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot , who jointly received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935 . Because of the declaration of war by France and England on Germany on September 3, 1939, he accompanied the transport of the entire French stocks of heavy water and the research documents for isotope separation to England in 1940 . From 1940 to May 1946 he worked for the British Admiralty in the HMA / SEE research laboratory of the Navy in Fairlie, Ayrshire a. a. in the field of sonar technology for the detection of submarines. He then lived in London with Stanley Byard at 44 Primrose Gardens and moved to Belize Grove No. 8 in June 1946.

While working in the research laboratory of the English Navy, he read books on neurophysiology and neuropsychology . During this time he also gave lectures to the British Association of Scientific Workers , which later formed the basis for his seminal book Body and mature behavior , published in 1949. In the same year he refused to set up his own institute in London with funds from private donors.

After the Second World War, Feldenkrais returned several times to Paris, where he was awarded the degree of Ingénieur Docteur from the Université Sorbonne in 1946/1947 . Evidence for this is his doctoral thesis Contribution à la mesure des hautes tensions from 1945 in the Bibliothèque Universitaire Pierre et Marie Curie and the mention of his doctorate in the Annales de l'Université de Paris 1947 . The doctors of physics in the Annales de l'Université are listed in a different category. In contrast to his learned profession as an engineer, Feldenkrais liked to call himself a physicist. There is no evidence of any other academic degrees that he could have acquired and with which he was sometimes titled. The information in numerous sources on the Internet and some biographies are therefore very contradictory.

In 1950 the Israeli government asked him to help build the newly established state of Israel. He initially worked there in a research institute of the Ministry of Defense, allegedly in the field of rocket technology. But it was quickly found out that he had no idea about it. From 1952 he devoted himself entirely to developing his own method and founded his own Feldenkrais Institute. From the late 1960s he trained the first generations of Feldenkrais teachers. Until his death in 1984 he taught in Tel Aviv and was invited to France, England and the USA to present his method. He trained the second and third generation of Feldenkrais teachers in training courses in the USA: San Francisco 1975–1978 and at Hampshire College in Amherst, 1980–1983.

His most famous students included David Ben-Gurion , the first Prime Minister of Israel, Yehudi Menuhin and Peter Brook . An important part of his work with private students was the support of disabled children.

Life as a martial artist

Feldenkrais was also a judo teacher for twenty years and wrote several books about it. In Palestine he began to deal intensively with hand-to-hand combat methods in the 1920s . According to the company (. Eg in an interview with Dennis Leri) he taught from 1921 members of the Hagana in self-defense . He established some of the basic concepts (e.g. using the natural defense reflexes) that were later further cultivated in the KAPAP or Krav Maga .

During his studies in Paris from 1930 he continued to deal with martial arts , in particular with Jiu Jitsu and the judo derived from it. To this end, he developed and published his own training methods, which Kanō Jigorō judged favorably. In September 1933 he met Kanō in Paris, with whom he then corresponded regularly and was friends. When the Japanese judo professor (Sensei) Mikinosuke Kawaishi moved from England to Paris in 1935, Kanō asked Feldenkrais to study Jiu Jitsu and Judo more closely with him. Following this advice, Feldenkrais began a long-term collaboration with Kawaishi. In 1936 he and Kawaishi founded the Jiu Jitsu Club de France , one of the oldest Jiu-Jitsu associations in Europe that still exists today.

The Kōdōkan awarded Feldenkrais in 1936 as the first European the 1st Dan Judo and two years later the 2nd Dan. His teaching work in the field of self-defense was also recognized by his colleagues in the Paris research laboratory. a. Frédéric Joliot, Irène Joliot-Curie and Bertrand Goldschmidt taught the basics of judo self-defense.

After the Second World War, he re-established contact with Kawaishi in 1946 and founded the Judo Club de France with him and other French Budo athletes , from which the French Judo Federation (Fédération française de judo, jujitsu, kendo et disciplines associées, FFJDA ) emerged . The FFJDA is now the national sports association of judoka and budo athletes in France.

Feldenkrais method

Moshé Feldenkrais assumed that a person acts according to the image they make of themselves and that this image is essentially linked to their experience of movement. This image (“self image”) is partly inherited, partly educated, and a third part comes about through self-education. Now if someone has the need to change their behavior, e.g. B. in order to achieve greater sporting or artistic achievements or to change pain-producing or otherwise harmful patterns of behavior or to find alternative patterns of behavior, this picture of oneself must be changed or expanded.

In order to achieve this, Feldenkrais developed an educational concept of learning through introspection and changing movement based on his decades of work as a judo teacher. These are not physical exercises in the conventional sense, but rather slowly and calmly executed sequences of movements that build on each other in small steps and invite you to try out and learn.

In practice, this can be taught in two different ways: as a verbal instruction for groups ("awareness through movement") and as individual work rather non-verbally, by means of sequences of movements carried out through touch. This individual work emphasizes the aspect of experienceability, understanding, changeability and integration of local, regional and global movement patterns (functional integration). Feldenkrais compiled an extensive collection of lessons (over 1000), which he constantly tried out and revised, as he always saw himself as a learner in dialogue with his clients.

His credo was the idea that what matters is not what you do, but how you do something. This “how” can be made tangible, questioned and changed. As a method of self-empowerment, this is an open learning concept that can be used in all areas of life. In the area of bodywork, it was important to him that language is largely withdrawn or not used at all so that the body can understand itself, experiment with itself and learn in its own language, namely the self-perception of movement. Since the method represents an open learning concept for all participants, the learning process always applies to both the client and the teacher. The lessons and case studies documented by transcripts and video recordings are therefore not blueprints, but the procedure must always be adapted to the needs of the clients and the teacher's own experience. Feldenkrais took lessons from Heinrich Jacoby, who wrote about him:

- Despite great physical agility, strength and courage, Dr. F. neither in his way of speaking nor in his quality of movement what he formulates 'theoretically' as desirable ... But he is very ready to admit that himself, ready to try and question it.

When developing his method, Feldenkrais was influenced, among other things, by:

- Gustav Theodor Fechner

- Frederick Matthias Alexander

- Berta Bobath

- Karel Bobath

- Gerda Alexander

- Fritz Perls

- Charlotte Selver

- Mabel Elsworth Todd

- Georges I. Gurdjieff

- Émile Coué

- Milton H. Erickson

- William Bates

- Milton Trager

Moshé Feldenkrais took lessons himself:

The aim of the Feldenkrais Method is to change and develop the elements of movement, sensation, feeling and thinking through the element of movement.

Fonts

- Jiu-jitsu , Étienne Chiron, Paris 1934.

- Judo pour ceintures noires. Étienne Chiron, Paris 1951.

- Higher judo. Ground Work (KATAME-WAZA). Frederick Warne & Co., London / New York 1953.

- Awareness through movement. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1968, ISBN 3-518-36929-6 .

- Adventure in the jungle of the brain. The Doris case. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-518-37163-0 .

- The discovery of the obvious. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-518-37940-2 .

- The Feldenkrais method in action. A holistic movement theory. 7th edition. Junfermann, Paderborn 2006, ISBN 978-3-87387-019-2 .

- The strong self. Instructions on spontaneity. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-518-38457-0 .

- The way to the mature self. Phenomena of human behavior. 2nd Edition. Junfermann, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 978-3-87387-126-7 .

literature

- Christian Buckard : Moshé Feldenkrais. The person behind the method. Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-8270-1238-8 .

- Norbert Klinkenberg: Moshé Feldenkrais and Heinrich Jacoby - An encounter. Series of publications by the Heinrich Jacoby / Elsa Gindler Foundation, Volume 1. Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-00-009762-7 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Moshé Feldenkrais in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ^ Frank Wildman: Feldenkrais. The Busy Person's Guide to Easier Movement. The Intelligent Body Press, Berkeley (CA) 2006, p. 3.

- ↑ a b c d Rainer Wenzel: Moshé Feldenkrais - The adventurous life . In: Kalonymos . tape 19 , no. 2 , 2016, p. 11-12 .

- ↑ library directory Catalog Sudok: Contribution à la mesure des Hautes tensions. Paris: Faculte des sciences, 1945, accessed July 8, 2018 (French).

- ^ Bibliothèque Universitaire Pierre et Marie Curie. Section Biologie-Chimie-Physique Recherche 4, place Jussieu Patio 13-24, RC (Saint-Bernard) Case courrier 261

- ↑ Annales de l'Université de Paris, No. 1, Janvier – Mars 1947. Sorbonne Paris V, 1947, p. 115 (in PDF 131) , accessed on July 8, 2018 (French).

- ↑ Haaretz magazine , July 1, 2015, section This day in Jewish History : 1984: The Father of Feldenkrais Dies .

- ↑ The moving personality . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung of April 27, 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Christian Buckard: Moshé Feldenkrais: The man behind the method. Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-8270-1238-8 , pp. 107-116

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Feldenkrais, Moshe |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Israeli physicist and martial arts teacher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 6, 1904 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Slavuta , Russian Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 1, 1984 |

| Place of death | Tel Aviv , Israel |