Fuxianhuia

| Fuxianhuia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fuxianhuia protensa |

||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||

| Cambrian (2nd series) | ||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||

|

China |

||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||

| Fuxianhuia | ||||||||

| Hou , 1987 | ||||||||

| species | ||||||||

|

||||||||

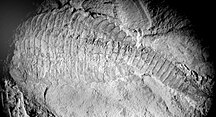

Fuxianhuia is a genus of extinct arthropods that has been fossilized in the Chengjiang Faunal Community in the second series of the Cambrian . Two species have been described, Fuxianhuia protensa in 1987 and Fuxianhuia xiaoshibaensis in 2013. The genus is one of the most important fossil representatives of the “higher” stem group of modern arthropods or Euarthropoda, whichtracestheir evolution from lobopod- like forms in the early Cambrian . Fuxianhuia fossilsare also famous for their sometimes extremely good preservation. In addition to the fossilized exoskeleton , fossils of soft tissues, including not only the intestines, but also traces of the central nervous system and the cardiovascular system, were found on them.

description

Fuxianhuia reached a maximum body length of about 11 centimeters. Three zones can be recognized on the body: a head with a head shield and various attachments, a trunk section and an abdomen or abdomen. The head consisted of a front section and a head shield, which lay loosely on the adjacent three trunk segments in the manner of a carapace , without being fused with them. The adjoining fuselage was composed of 13 to 15 segments, the tergites of which were expanded on both sides by widenings called pleurs. The abdomen, on the other hand, is abruptly narrowed. It consisted of a further 13 segments which, in contrast to the trunk segments, did not carry any limbs. At the end of the body sat an end pin, which was flanked by two lateral thorns.

head

The head consisted of an almost circular sclerite, at the rear end of which the semicircular head shield was attached. A little separated from the sclerite there was also a separate small appendix with two clearly stalked eyes. These were possibly designed as compound eyes , but this was only directly proven in the related Chengjiangocaris longiformis . On the underside was a head flap or hypostome, which reached about a third of the length of the shield; at its rear end was the mouth opening. Head appendages were a pair of relatively short, one-branched (uniramen), articulated antennae that were deflected in front of the front end of the hypostome (or behind the rear edge of the head sclerite). Behind it, on both sides of the mouth opening and the hypostome, sat a pair of short mouth limbs that were directed backwards, these were tripartite and single-branched, the end limb, which made up about half the total length, had a blunt end without teeth or points. The first fossils of Fuxianhuia protensa found were poorly preserved, so that their nature was initially controversial; some researchers even thought they were only impressions of diverticula of the intestine. It is believed that the appendages of the mouth carried soft nutritional substrate, such as nutrient-rich mud, to the mouth. The function of the antennae was presumably purely sensory, without taking part in food intake. There are no references to chewing stores (Gnathobases). The three trunk segments covered by the head shield carried two-branched (birame) split legs , which did not differ in the structure in the least from the extremities of the adjacent trunk.

Trunk and abdomen

13 to 15 tergites can be seen on the trunk , which are opposed to 35 to 45 pairs of legs, so it is obvious that each tergite did not correspond to a pair of legs, as is the case with recent arthropods. In Fuxianhuia xiaoshibaensis , the first five tergites behind the mouth each correspond to a pair of legs, in the following there are three or four each in both species. Each leg consisted of an articulated exopodite of about 25 similar (homonomous) limbs, which was probably used for walking, and a thin, oval, leaf-shaped exopodite without articulation. Claws or other attachments are not recognizable. So the leg articulation was quite primitive with no discernible specializations. In the living animal, the legs did not protrude beyond the lateral appendages of the tergites (paratergites), so they were not visible from above. They decreased in size towards the back, but were otherwise completely identical. The abdomen had no extremities or other special formations.

Brain and nervous system

A fossil preservation of neural tissue seems almost impossible and has been observed extremely rarely. But it has also been observed in another fossil arthropod species from the Cambrian. It was discovered at Fuxianhuia portensa in 2012 and later confirmed in a number of other fossils, so that a deception caused by taphonomic processes seems almost impossible. A bridge-like connection between the eyes and the eye stalks can be seen (which, according to their location in the fossil material, were probably quite mobile). The seldom preserved actual brain reaches about the size of recent Malacostraca . Paired longitudinal strands ( connective ) and structures can be recognized that could correspond to the mushroom bodies and the optical tract (with three neuropiles ) of recent arthropods. The brain is clearly made up of three parts ( Syncerebrum from Protocerebrum, Deutocerebrum and Tritocerebrum), the Tritocerebrum was not separated from the other brain parts as in the recent Branchiopoda . The antenna nerve opening into the Deutocerebrum is recognizable. In addition to the details mentioned, this discovery is also significant for the homologation of the head segments. The innervation of the antennae from the Deutocerebrum shows that they are homologous to the antennae of the Euarthropoda , not those of the Onychophora , which are innervated by the Protocerebrum.

Heart and blood vessel system

In contrast to the nervous system, fossilized tissue of the cardiovascular system is only found in one specimen. There is a typical arthropod heart with segmentally arranged valves (two per tergite on the posterior tergites) with an artery that is extended towards the head and splits into two symmetrical branches in the head area, which were obviously connected by anastomoses. Laxative arteries, which presumably supplied the legs, are visible at regular intervals.

Phylogeny

Fuxianhuia belongs to a group of similar, presumably related fossil forms, which are circumscribed as "Fuxianhuiden"; Xianguang Hou, the discoverer of the Chengjiang fauna and the first to describe the genus, regards them as the order Fuxianhuiida. Not all editors followed him in this. The group includes, in addition to the two species of the genus, Chengjiangocaris with the species Chengjiangocaris kumingensis and Chengjiangocaris longiformis , Guangweicaris spinatus , Liangwangshania biloba and Shankouia zhenghi , all from the Chengjiang Fauna Community of China. Similar fossils from the Canadian Rockies have been briefly reported, but have not been described . Fuxianhuiden show numerous features of the Euarthropoda, for example articulated legs that can be homologated with the split legs of the crustaceans , complex eyes, specialized head limbs such as antennae and mouthparts, which largely correspond to those of basal euarthropods in terms of fine structure and position. The possession of real antennae, which are located on the second (deutocerebral) head segment, sets them apart from the Chelicerata and a group of trunk group arthropods (the "Megacheira"), which share a greatly elongated antenna member that has been converted for food acquisition. Primitive features of Fuxianhuia are, for example, the head, which is still imperfectly differentiated from the trunk, and the legs made up of numerous similar limbs.

In the more recent cladistic analyzes, this results in a position directly basal to the Euarthropoda, which could possibly be their direct sister group . Their position in relation to other fossil arthropods such as the Megacheira (or a subgroup of them), another group of extinct arthropods with two-lobed shells such as Isoxys and Branchiocaris or the genus Guangweicaris is not certain, and new fossils are regularly discovered.

swell

- Xian-guag Hou, Richard Aldridge, Jan Bergström, David J. Siveter, Derek Siveter, Xiang-Hong Feng: The Cambrian Fossils of Chengjiang , China: The Flowering of Early Animal Life. Wiley, 2008. ISBN 978-04-7099994-3 ( limited preview in Google Book Search)

- Jie Yang, Javier Ortega-Hernandez, Nicholas J. Butterfield, Xi-guang Zhang (2013): Specialized appendages in fuxianhuiids and the head organization of early euarthropods. Nature 494: 468-471 + appendages. doi : 10.1038 / nature11874

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Xiaoya Ma, Xianguang Hou, Gregory D. Edgecombe, Nicholas J. Strausfeld (2012): Complex brain and optic lobes in an early Cambrian arthropod. Nature 490: pp. 258-261 + appendages.

- ↑ Gengo Tanaka, Xianguang Hou, Xiaoya Ma, Gregory D. Edgecombe, Nicholas J. Strausfeld (2013): Chelicerate neural ground pattern in a Cambrian great appendage arthropod. Nature 502: pp. 364-367 + appendages. doi : 10.1038 / nature12520

- ↑ Xiaoya Ma, Gregory D. Edgecombe, Xianguang Hou, Tomasz Goral, Nicholas J. Strausfeld (2015): Preservational Pathways of Corresponding Brains of a Cambrian Euarthropod. Current Biology 25: 2969-2975. doi : 10.1016 / j.cub.2015.09.063

- ↑ Xiaoya Ma, Peiyun Cong, Xianguang Hou, Gregory D. Edgecombe, Nicholas J. Strausfeld (2014): An exceptionally preserved arthropod cardiovascular system from the early Cambrian. Nature Communications 5: 3560. doi : 10.1038 / ncomms4560

- ^ David A. Legg: The impact of fossils on arthropod phylogeny. Thesis, Imperial College, London. P. 58.

- ^ Jean-Bernard Caron, Robert R. Gaines, M. Gabriela Mángano, Michael Streng, Allison C. Daley (2010): A new Burgess Shale - type assemblage from the “thin” Stephen Formation of the southern Canadian Rockies. Geology 38 (9): pp. 811-814.

- ↑ Graham E. Budd & Maximilian J. Telford (2009): The origin and evolution of arthropods. Nature 457: pp. 812-817. doi : 10.1038 / nature07890

- ↑ David A. Legg, Mark D. Sutton, Gregory D. Edgecombe (2013): Arthropod fossil data increase congruence of morphological and molecular phylogenies. Nature Communications 4: 2485. doi : 10.1038 / ncomms3485

- ↑ Gregory D. Edgecombe & David A. Legg (2014): Origins and early evolution of arthropods. Palaeontology, 2014: 1-12. doi : 10.1111 / pala.12105

- ↑ Javier Ortega-Hernández (2014): Making sense of 'lower' and 'upper' stem-group Euarthropoda, with comments on the strict use of the name Arthropoda von Siebold, 1848. Biological Revues of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 2014 doi : 10.1111 /brv.12168 (online before print)

- ↑ Luo Huilin; Fu Xiaoping; Hu Shixue; Li Yong; Hou Shuguang; You ting; Pang jiyuan; Liu Qi (2007): A New Arthropod, Guangweicaris Luo, Fu et Hu gen. Nov. from the Early Cambrian Guanshan Fauna, Kunming, China. Acta Geologica Sinica 81 (1) : pp. 1-7.

Web links

- Fossil Focus: Cambrian arthropods, by David A. Legg.http: //www.palaeontologyonline.com.Retrieved November 17, 2015

- 500 million-year-old evolutionary link found in Yunnan www.gokunming.com accessed on November 17, 2015